Native Species Response to Goat Foraging in a Shrub-Invaded California Coastal Grassland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

More Mesa Plant Guide

More Mesa Plant Guide Coastal Woodfern Miniature Lupine Sky Lupine Arroyo Lupine Dryopteris arguta 1 Lupinus bicolor 2 Lupinus nanus 3 Lupinus succulentus 2 Pinpoint Clover White-tipped Clover Deerweed Desert Lotus Trifolium gracilentum 4 Trifolium variegatum 5 Acmispon glaber 3 Acmispon strigosus 3 Chaparral Lotus California Blackberry Toyon California Rose Acmispon grandiflorus Rubus ursinus 6 Heteromeles arbutifolia 3 Rosa californica 3 grandiflorus 3 Sticky Cinquefoil California Coffeeberry Stinging Nettle Pigmyweed Drymocallis glandulosa Frangula californica 6 Urtica dioica 6 Crassula aquatica 7 glandulosa 3 Pygmy Stonecrop Narrowleaf Milkweed Seacliff Wild Willow Dock Crassula connata 3 Asclepias fascicularis 3 Buckwheat Rumex salicifolius 8 Eriogonum parvifolium 6 Willow Weed Dotted Knotweed California Goosefoot Pacific Pickleweed Persicaria lapathifolia 9 Persicaria punctata 10 Chenopodium Salicornia pacifica 11 californicum 3 Spearscale Big Saltbush Saltmarsh Sand- Prostrate Amaranth Atriplex prostrata 6 Atriplex lentiformis spurrey Amaranthus blitoides 13 lentiformis 3 Spergularia marina 12 Redmaids Miner's Lettuce Short Styled Thistle California Brittlebush Calandrinia ciliata 6 Claytonia perfoliata 3 Cirsium brevistylum 3 Encelia californica 3 Horseweed Marsh Baccharis Coyote Brush Mule Fat Erigeron canadensis 6 Baccharis glutinosa 6 Baccharis pilularis 3 Baccharis salicifolia 6 California Sagebrush Mugwort Western Ragweed California Cudweed Artemisia californica 3 Artemisia douglasiana 2 Ambrosia psilostachya 14 Pseudognaphalium -

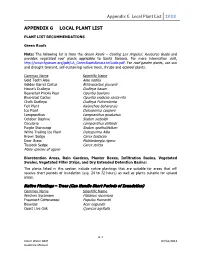

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX G LOCAL PLANT LIST PLANT LIST RECOMMENDATIONS Green Roofs Note: The following list is from the Green Roofs – Cooling Los Angeles: Resource Guide and provides vegetated roof plants applicable to Santa Barbara. For more information visit, http://www.fypower.org/pdf/LA_GreenRoofsResourceGuide.pdf. For roof garden plants, use sun and drought tolerant, self-sustaining native trees, shrubs and ecoroof plants. Common Name Scientific Name Gold Tooth Aloe Aloe nobilis Golden Barrel Cactus Echinocactus grusonii Hasse’s Dudleya Dudleya hassei Beavertail Prickly Pear Opuntia basilaris Blue-blad Cactus Opuntia violacea santa-rita Chalk Dudleya Dudleya Pulverulenta Felt Plant Kalanchoe beharensis Ice Plant Delosperma cooperii Lampranthus Lampranthus productus October Daphne Sedum sieboldii Oscularia Lampranthus deltoids Purple Stonecrop Sedum spathulifolium White Trailing Ice Plant Delosperma Alba Brown Sedge Carex testacea Deer Grass Muhlenbergia rigens Tussock Sedge Carex stricta Many species of agave Bioretention Areas, Rain Gardens, Planter Boxes, Infiltration Basins, Vegetated Swales, Vegetated Filter Strips, and Dry Extended Detention Basins: The plants listed in this section include native plantings that are suitable for areas that will receive short periods of inundation (e.g. 24 to 72 hours) as well as plants suitable for upland areas. Native Plantings – Trees (Can Handle Short Periods of Inundation) Common Name Scientific Name Western Sycamore Platanus racemosa Freemont Cottonwood Populus fremontii -

Tidal Marsh Vegetation of China Camp, San Pablo Bay, California Peter R

AUGUST 2012 Tidal Marsh Vegetation of China Camp, San Pablo Bay, California Peter R. Baye1 ABSTRACT vegetation. Narrow high tidal marsh ecotones that borders terrestrial grasslands are locally dominated China Camp (Marin County, California) preserves by creeping wildrye (Elymus triticoides) and Baltic extensive relict stands of salt marsh vegetation rush (Juncus balticus), mostly on south-facing slopes. developed on a prehistoric salt marsh platform with Brackish tidal marsh ecotones above ordinary high a complex sinuous tidal creek network. The low salt tides are associated with freshwater discharges from marsh along tidal creeks supports extensive native groundwater and surface flows. Brackish marsh eco- stands of Pacific cordgrass (Spartina foliosa). After tones support large clonal stands of sedge, bulrush, hydraulic gold mining sedimentation, the outer and rush vegetation (Carex praegracilis, C. barbarae, salt marsh accreted. It consists of a wave-scarped Bolboschoenus maritimus, Juncus phaeocephalus, pickleweed-dominated (Sarcocornia pacifica) high Schoenoplectus acutus), intergrading with terrestrial salt marsh terrace, with a broad fringing low marsh freshwater wetlands and salt marsh. The terrestrial dominated by S. foliosa, including intermittent, vari- ecotone assemblages at China Camp are comparable able stands of alkali-bulrush (Bolboschoenus mari- with those of other prehistoric tidal marshes in the timus). Most of the extensive prehistoric salt marsh San Francisco Estuary, but China Camp lacks most plains within the tidal creek network also support native clonal perennial Asteraceae and halophytic mixed assemblages of S. pacifica, but high marsh annual forbs of the region’s remnant high tidal marsh zones along tidal creek banks support nearly continu- ecotones. Few globally-rare salt marsh plant popula- ous linear stands of gumplant (Grindelia stricta) and tions have been reported from China Camp within saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) with more diverse salt the National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) and marsh forb assemblages. -

DRAFT OAEC NATIVE PLANT LIST FERNS and FERN ALLIES

DRAFT OAEC NATIVE PLANT LIST FERNS and FERN ALLIES: Blechnaceae: Deer Fern Family Giant Chain Fern Woodwardia fimbriata Dennstaedtiaceae: Bracken Fern Bracken Pteridium aquilinum Dryopteridaceae: Wood Fern Family Lady Fern Athyrium filix-femina Wood Fern Dryopteris argutanitum Western Sword Fern Polystichum muitum Polypodiaceae: Polypody Family California Polypody Polypodium californicum Pteridaceae: Brake Family California Maiden-Hair Adiantum jordanii Coffee Fern Pellaea andromedifolia Goldback Fern Pentagramma triangularis Isotaceae: Quillwort Family Isoetes sp? Nuttallii? Selaginellaceae: Spike-Moss Family Selaginella bigelovii GYMNOPSPERMS Pinaceae: Pine Family Douglas-Fir Psuedotsuga menziesii Taxodiaceae: Bald Cypress Family Redwood Sequoia sempervirens ANGIOSPERMS: DICOTS Aceraceae: Maple Family Big-Leaf Maple Acer macrophyllum Box Elder Acer negundo Anacardiaceae: Sumac Family Western Poison Oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Apiaceae: Carrot Family Lomatium( utriculatum) or (carulifolium)? Pepper Grass Perideridia kelloggii Yampah Perideridia gairdneri Sanicula sp? Sweet Cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Unidentified in forest at barn/deer fence gate Angelica Angelica tomentosa Apocynaceae: Dogbane or Indian Hemp Family Apocynum cannabinum Aristolochiaceae Dutchman’s Pipe, Pipevine Aristolochia californica Wild Ginger Asarum caudatum Asteraceae: Sunflower Family Grand Mountain Dandelion Agoseris grandiflora Broad-leaved Aster Aster radulinus Coyote Brush Baccharis pilularis Pearly Everlasting Anaphalis margaritacea Woodland Tarweed Madia -

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California

Classification of the Vegetation Alliances and Associations of Sonoma County, California Volume 1 of 2 – Introduction, Methods, and Results Prepared by: California Department of Fish and Wildlife Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program California Native Plant Society Vegetation Program For: The Sonoma County Agricultural Preservation and Open Space District The Sonoma County Water Agency Authors: Anne Klein, Todd Keeler-Wolf, and Julie Evens December 2015 ABSTRACT This report describes 118 alliances and 212 associations that are found in Sonoma County, California, comprising the most comprehensive local vegetation classification to date. The vegetation types were defined using a standardized classification approach consistent with the Survey of California Vegetation (SCV) and the United States National Vegetation Classification (USNVC) system. This floristic classification is the basis for an integrated, countywide vegetation map that the Sonoma County Vegetation Mapping and Lidar Program expects to complete in 2017. Ecologists with the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Native Plant Society analyzed species data from 1149 field surveys collected in Sonoma County between 2001 and 2014. The data include 851 surveys collected in 2013 and 2014 through funding provided specifically for this classification effort. An additional 283 surveys that were conducted in adjacent counties are included in the analysis to provide a broader, regional understanding. A total of 34 tree-overstory, 28 shrubland, and 56 herbaceous alliances are described, with 69 tree-overstory, 51 shrubland, and 92 herbaceous associations. This report is divided into two volumes. Volume 1 (this volume) is composed of the project introduction, methods, and results. It includes a floristic key to all vegetation types, a table showing the full local classification nested within the USNVC hierarchy, and a crosswalk showing the relationship between this and other classification systems. -

Botanical Inventory of Pinnacles National Monument's New Lands

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Pacific West Region Oakland, CA Botanical Inventory of Pinnacles National Monument’s New Lands A Volunteer Botany Inventory Natural Resource Report NPS/PWR/SFAN/NRTR—2008/083 ON THE COVER Volunteers prepare to grid part of the new lands at Pinnacles, flagging any unknown plants Photograph by: Elizabeth Speith, Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy Botanical Inventory of Pinnacles National Monument’s New Lands A Volunteer Botany Inventory Natural Resource Report NPS/PWR/SFAN/NRTR—2008/083 Andrea Williams National Park Service San Francisco Bay Area Network Fort Cronkhite Building 1063 Sausalito, California 94965 January 2008 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Pacific West Regional Office Oakland, California ii The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; monitoring protocols; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters. -

California Wetlands

VOL. 46, NO.2 FREMONTIA JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY California Wetlands 1 California Native Plant Society CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1; Sacramento, CA 95816-5130 Phone: (916) 447-2677 • Fax: (916) 447-2727 FREMONTIA www.cnps.org • [email protected] VOL. 46, NO. 2, November 2018 Memberships Copyright © 2018 Members receive many benefits, including a subscription toFremontia California Native Plant Society and the CNPS Bulletin. Look for more on inside back cover. ISSN 0092-1793 (print) Mariposa Lily.............................$1,500 Family..............................................$75 ISSN 2572-6870 (online) Benefactor....................................$600 International or library...................$75 Patron............................................$300 Individual................................$45 Gordon Leppig, Editor Plant lover.....................................$100 Student/retired..........................$25 Michael Kauffmann, Editor & Designer Corporate/Organizational 10+ Employees.........................$2,500 4-6 Employees..............................$500 7-10 Employees.........................$1,000 1-3 Employees............................$150 Staff & Contractors Dan Gluesenkamp: Executive Director Elizabeth Kubey: Outreach Coordinator Our mission is to conserve California’s Alfredo Arredondo: Legislative Analyst Sydney Magner: Asst. Vegetation Ecologist native plants and their natural habitats, Christopher Brown: Membership & Sales David Magney: Rare Plant Program Manager and increase understanding, -

Appendix C Appendix C SPECIAL-STATUS SPECIES INVENTORY

Appendix C Appendix C SPECIAL-STATUS SPECIES INVENTORY Special-Status Species Inventory for the Santa Barbara Airport Master Plan Update Prepared for: Coffman Associates C/O James M. Harris 4835 East Cactus Road, Suite 235 Scottsdale, AZ 85254 602.993.6999 Prepared by: 621 Chapala Street Santa Barbara, CA 93101 Contact: John H. Davis IV, Senior Ecologist 805.963.0651 OCTOBER 2012 C-1 C-2 Santa Barbara Airport Special-Status Species Inventory TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page No. 1.0 INTRODUCTION..............................................................................................................1 1.1 Airport Location...................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Airport Master Plan................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Biological Setting.................................................................................................... 5 1.3.1 History of the Airport and Goleta Slough ................................................... 5 1.3.2 Airport Safety and Wildlife Management................................................... 6 1.3.3 Habitat Restoration in the Goleta Slough ................................................... 7 1.3.4 Existing Sensitive Biological Resources .................................................... 9 2.0 METHODS .......................................................................................................................11 2.1 Special-Status Species Defined............................................................................ -

3-Web PP Plant List

Wild Plants of Point Pinole Regional Shoreline Grouped by Growth Form Alphabetical by Scientific Name September 5, 2003 Wild Plants of Point Pinole Regional Shoreline Grouped by Growth Form Alphabetical by Scientific Name This document contains a comprehensive list of the wild plants reported to be found in Point Pinole Regional Shoreline. The plants are grouped according to their growth form for easy accessibility. These four groups are: Ferns & Horsetails, Grasses & Grasslike, Herbaceous, and Woody. The plants within each group are listed alphabetically by scientific name. Other information on each plant includes the common name, family, whether the plant is native or introduced, and its longevity. For quick reference, the upper left corner of each page displays both the group name (based on growth form) and the genus of the first scientific name. The abbreviations used: Checklist column for marking off the plants you observe Scientific Name According to The Jepson Manual: Higher Plants of California, 1993 Common Name According to Jepson and other references (highly variable) Family The scientific plant family name according to Jepson L Longevity: Annual (a), Biennial (b), Perennial (p), or a combination N/I Native (n) or Introduced (i) according to Jepson The listing of plants included in this document is by no means complete. The intent is to maintain an ongoing inventory to which additional plants can be added over time. Readers are encouraged to report any corrections or additions to this list by emailing the District Botanist (Wilde Legard, [email protected]). This welcomed assistance will help facilitate improved management of the Park District’s natural resources. -

A Sensitive Plant and Wildlife Resource Inventory of Diablo Canyon Lands, Volume Ii

A SENSITIVE PLANT AND.WILDLIFE RESOURCE INVENTORY OF DIABLO CANYON LANDS, VOLUME I: SURVEY PROCEDURES AND A SUMMARY OF SURVEY RESULTS Prepared by: BioSystems Analysis, Inc. 303 Potrero Street, Suite 29-101 Santa Cruz, California 95060 and Pacific Gas and Electric Company Technical and Ecological Services 3400 Crow Canyon Road San Ramon, California 94583 Prepared for: Pacific Gas and Electric Company Diablo Canyon Land Stewardship Committee Diablo Canyon Power Plant Avila Beach, California © 1995 by PG&E (Revised 1996) Legal Notice Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) makes no warranty or representation, expressed or implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the information contained in this report, or that the use of any information, apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report may not infringe upon privately owned rights. Nor does PG&E assume any liability with respect to use of, or damages resulting from the use of, any information, apparatus, method, or process disclosed in this report. © 1995 by PG&E All rights reserved EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PG&E owns or controls through long-term lease agreements approximately 10,000 acres of ecologically diverse coastal lands surrounding Diablo Canyon Power Plant in San Luis Obispo County, California. Beginning in 1992, a comprehensive survey of these lands was undertaken to identify and describe all sensitive plant and wildlife resources not previously known that might occur there. Though not required by state or federal regulatory agencies, this voluntary effort is consistent with PG&E's Corporate Policy on Management of Company Real Property (Section 7, paragraphs a and d), as well as specific Best Management Practices identified by the Diablo Canyon Land Stewardship Program (PG&E 1993a). -

Plant Identification of Younger Lagoon Reserve

Plant Identification of Younger Lagoon Reserve A guide written by Rebecca Evans with help from Dr. Karen Holl, Elizabeth Howard, and Timothy Brown 1 Table of Contents Introduction to Plant Identification ............................................................................................. 3 Plant Index ................................................................................................................................. 6 Botanical Terminology ............................................................................................................. 12 Habits, Stem Conditions, Root Types ................................................................................ 12 Leaf Parts .......................................................................................................................... 13 Stem Features .................................................................................................................... 14 Leaf Arrangements ............................................................................................................ 16 Leaf Shape ........................................................................................................................ 18 Leaf Margins and Venation ............................................................................................... 20 Flowers and Inflorescences ................................................................................................ 21 Grasses ............................................................................................................................. -

Using Native Plants for Your • Yard • Patio • Creek

GO NATIVE Using Native Plants FOR YOUR • Yard • Patio • Creek MarinMarin County County Stormwater Stormwater PollutionPollution Prevention Prevention ProgramProgram www.mcstoppp.org415-473-3202 www.mcstoppp.org Acknowledgments: MCSTOPPP gratefully acknowledges the assistance provided by Debi Tidd and Patrice Hanlon of The Gardens at Heather Farm, Doreen Smith of the CA Native Plant Society, Marin Chapter, David Herlocker and Mischon Martin of Marin County Parks and Open Space District, and Charlotte Torgovitsky of the Marin Art and Garden Center. Project Management: Gina Purin Editors: Jo Charlton, Liz Lewis, Gina Purin Graphic Design: Lisa Krieshok, Petaluma, CA Copies of this publication should not be made without permission. Call MCSTOPPP at 415-473-6528. If you are a person with a disability and require materials in alternative formats, please call: 415 473-4381 (Voice) or CRS 711 or email [email protected] . MCSTOPPP Marin County Stormwater Pollution Prevention Program PO Box 4186 San Rafael, CA 94913-4186 Printed on Recycled Paper Table of Contents Why Use Native Plants? .......................................................................3 Tips on Planting “Natives” ...................................................................3 Where to Buy Natives ...........................................................................4 When and What to Plant .....................................................................5 Sowing Wildflower Seeds ............................................................5 Native