+ Traversing Swanton Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changes at a Critical Branchpoint in the Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway Underlie the Blue to Orange Flower Color Transition in Lysimachia Arvensis

fpls-12-633979 February 16, 2021 Time: 19:16 # 1 ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 22 February 2021 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.633979 Changes at a Critical Branchpoint in the Anthocyanin Biosynthetic Pathway Underlie the Blue to Orange Flower Color Transition in Lysimachia arvensis Edited by: Mercedes Sánchez-Cabrera1*†‡, Francisco Javier Jiménez-López1‡, Eduardo Narbona2, Verónica S. Di Stilio, Montserrat Arista1, Pedro L. Ortiz1, Francisco J. Romero-Campero3,4, University of Washington, Karolis Ramanauskas5, Boris Igic´ 5, Amelia A. Fuller6 and Justen B. Whittall7 United States 1 2 Reviewed by: Department of Plant Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Biology, University of Seville, Seville, Spain, Department of Molecular 3 Stacey Smith, Biology and Biochemical Engineering, Pablo de Olavide University, Seville, Spain, Institute for Plant Biochemistry 4 University of Colorado Boulder, and Photosynthesis, University of Seville – Centro Superior de Investigación Científica, Seville, Spain, Department 5 United States of Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence, University of Seville, Seville, Spain, Department of Biological Science, 6 Carolyn Wessinger, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL, United States, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Santa Clara 7 University of South Carolina, University, Santa Clara, CA, United States, Department of Biology, College of Arts and Sciences, Santa Clara University, United States Santa Clara, CA, United States *Correspondence: Mercedes Sánchez-Cabrera Anthocyanins are the primary pigments contributing to the variety of flower colors among [email protected] angiosperms and are considered essential for survival and reproduction. Anthocyanins † ORCID: Mercedes Sánchez-Cabrera are members of the flavonoids, a broader class of secondary metabolites, of which orcid.org/0000-0002-3786-0392 there are numerous structural genes and regulators thereof. -

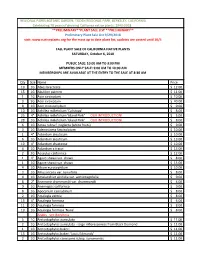

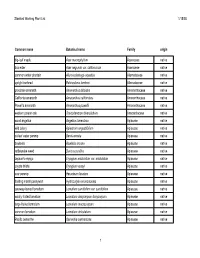

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Antileishmanial Compounds from Nature - Elucidation of the Active Principles of an Extract from Valeriana Wallichii Rhizomes

ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 Eingereicht am ....................................... bei der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie 1. Gutachter Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Gutachter ........................................ der Dissertation 1. Prüfer Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Prüfer ......................................... 3. Prüfer ......................................... des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums Datum des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums .................................................. Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am .................................................. "Wer nichts als Chemie versteht, versteht auch die nicht recht." Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799) DANKSAGUNG Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde am Institut für Pharmazie und Lebensmittelchemie der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg auf Anregung und unter Anleitung von Frau Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe und finanzieller Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 630) angefertigt. Ich -

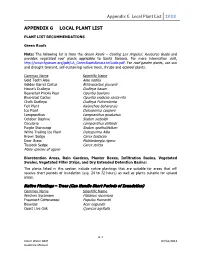

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX G LOCAL PLANT LIST PLANT LIST RECOMMENDATIONS Green Roofs Note: The following list is from the Green Roofs – Cooling Los Angeles: Resource Guide and provides vegetated roof plants applicable to Santa Barbara. For more information visit, http://www.fypower.org/pdf/LA_GreenRoofsResourceGuide.pdf. For roof garden plants, use sun and drought tolerant, self-sustaining native trees, shrubs and ecoroof plants. Common Name Scientific Name Gold Tooth Aloe Aloe nobilis Golden Barrel Cactus Echinocactus grusonii Hasse’s Dudleya Dudleya hassei Beavertail Prickly Pear Opuntia basilaris Blue-blad Cactus Opuntia violacea santa-rita Chalk Dudleya Dudleya Pulverulenta Felt Plant Kalanchoe beharensis Ice Plant Delosperma cooperii Lampranthus Lampranthus productus October Daphne Sedum sieboldii Oscularia Lampranthus deltoids Purple Stonecrop Sedum spathulifolium White Trailing Ice Plant Delosperma Alba Brown Sedge Carex testacea Deer Grass Muhlenbergia rigens Tussock Sedge Carex stricta Many species of agave Bioretention Areas, Rain Gardens, Planter Boxes, Infiltration Basins, Vegetated Swales, Vegetated Filter Strips, and Dry Extended Detention Basins: The plants listed in this section include native plantings that are suitable for areas that will receive short periods of inundation (e.g. 24 to 72 hours) as well as plants suitable for upland areas. Native Plantings – Trees (Can Handle Short Periods of Inundation) Common Name Scientific Name Western Sycamore Platanus racemosa Freemont Cottonwood Populus fremontii -

Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 9-17-2018 Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Redwood National Park" (2018). Botanical Studies. 85. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/85 This Flora of Northwest California-Checklists of Local Sites is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS OF THE REDWOOD NATIONAL & STATE PARKS James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State Univerity Arcata, California 14 September 2018 The Redwood National and State Parks are located in Del Norte and Humboldt counties in coastal northwestern California. The national park was F E R N S established in 1968. In 1994, a cooperative agreement with the California Department of Parks and Recreation added Del Norte Coast, Prairie Creek, Athyriaceae – Lady Fern Family and Jedediah Smith Redwoods state parks to form a single administrative Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosporum • northwestern lady fern unit. Together they comprise about 133,000 acres (540 km2), including 37 miles of coast line. Almost half of the remaining old growth redwood forests Blechnaceae – Deer Fern Family are protected in these four parks. -

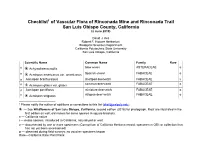

Rinconada Checklist-02Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Rinconada Mine and Rinconada Trail San Luis Obispo County, California (2 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Achyrachaena mollis blow wives ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon americanus var. americanus Spanish-clover FABACEAE o n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE o n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE o 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known Rare—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Acmispon wrangelianus California deervetch FABACEAE v n ❀ Acourtia microcephala sacapelote ASTERACEAE o n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. chamise ROSACEAE o fasciculatum n Adiantum jordanii California maidenhair fern PTERIDACEAE o n Agastache urticifolia nettle-leaved horsemint LAMIACEAE v n ❀ Agoseris grandiflora var. grandiflora large-flowered mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. cryptopleura annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE v n Agoseris heterophylla var. heterophylla annual mountain-dandelion ASTERACEAE o i Aira caryophyllea silver hairgrass POACEAE o n Allium fimbriatum var. -

Plant List for Web Page

Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 Common name Botanical name Family origin big-leaf maple Acer macrophyllum Aceraceae native box elder Acer negundo var. californicum Aceraceae native common water plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica Alismataceae native upright burhead Echinodorus berteroi Alismataceae native prostrate amaranth Amaranthus blitoides Amaranthaceae native California amaranth Amaranthus californicus Amaranthaceae native Powell's amaranth Amaranthus powellii Amaranthaceae native western poison oak Toxicodendron diversilobum Anacardiaceae native wood angelica Angelica tomentosa Apiaceae native wild celery Apiastrum angustifolium Apiaceae native cutleaf water parsnip Berula erecta Apiaceae native bowlesia Bowlesia incana Apiaceae native rattlesnake weed Daucus pusillus Apiaceae native Jepson's eryngo Eryngium aristulatum var. aristulatum Apiaceae native coyote thistle Eryngium vaseyi Apiaceae native cow parsnip Heracleum lanatum Apiaceae native floating marsh pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Apiaceae native caraway-leaved lomatium Lomatium caruifolium var. caruifolium Apiaceae native woolly-fruited lomatium Lomatium dasycarpum dasycarpum Apiaceae native large-fruited lomatium Lomatium macrocarpum Apiaceae native common lomatium Lomatium utriculatum Apiaceae native Pacific oenanthe Oenanthe sarmentosa Apiaceae native 1 Stanford Working Plant List 1/15/08 wood sweet cicely Osmorhiza berteroi Apiaceae native mountain sweet cicely Osmorhiza chilensis Apiaceae native Gairdner's yampah (List 4) Perideridia gairdneri gairdneri Apiaceae -

Download the *.Pdf File

ECOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE PROPOSED BIG PINE MOUNTAIN RESEARCH NATURAL AREA LOS PADRES NATIONAL FOREST, SANTA BARBARA COUNTY, CALIFORNIA TODD KEELER-WOLF FEBRUARY 1991 (PURCHASE ORDER # 40-9AD6-9-0407) INTRODUCTION 1 Access 1 PRINCIPAL DISTINGUISHING FEATURES 2 JUSTIFICATION FOR ESTABLISHMENT 4 Mixed Coniferous Forest 4 California Condor 5 Rare Plants 6 Animal of Special Concern 7 Biogeographic Significance 7 Large Predator and Pristine Environment 9 Riparian Habitat 9 Vegetation Diversity 10 History of Scientific Research 11 PHYSICAL AND CLIMATIC CONDITIONS 11 VEGETATION AND FLORA 13 Vegetation Types 13 Sierran Mixed Coniferous Forest 13 Northern Mixed Chaparral 22 Canyon Live Oak Forest 23 Coulter Pine Forest 23 Bigcone Douglas-fir/Canyon Live Oak Forest 25 Montane Chaparral 26 Rock Outcrop 28 Jeffrey Pine Forest 28 Montane Riparian Forest 31 Shale Barrens 33 Valley and Foothill Grassland 34 FAUNA 35 GEOLOGY 37 SOILS 37 AQUATIC VALUES 38 CULTURAL VALUES 38 IMPACTS AND POSSIBLE CONFLICTS 39 MANAGEMENT CONCERNS 40 BOUNDARY CHANGES 40 RECOMMENDATIONS 41 LITERATURE CITED 41 APPENDICES 41 Vascular Plant List 43 Vertebrate List 52 PHOTOGRAPHS AND MAPS 57 INTRODUCTION The Big Pine Mountain candidate Research Natural Area (RNA) is on the Santa Lucia Ranger District, Los Padres National Forest, in Santa Barbara County, California. The area was nominated by the National Forest as a candidate RNA in 1986 to preserve an example of the Sierra Nevada mixed conifer forest for the South Coast Range Province. The RNA as defined in this report covers 2963 acres (1199 ha). The boundaries differ from those originally proposed by the National Forest (map 5, and see discussion of boundaries in later section). -

Download The

SYSTEMATICA OF ARNICA, SUBGENUS AUSTROMONTANA AND A NEW SUBGENUS, CALARNICA (ASTERACEAE:SENECIONEAE) by GERALD BANE STRALEY B.Sc, Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 1968 M.Sc, Ohio University, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Botany) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March 1980 © Gerald Bane Straley, 1980 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department nf Botany The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 26 March 1980 ABSTRACT Seven species are recognized in Arnica subgenus Austromontana and two species in a new subgenus Calarnica based on a critical review and conserva• tive revision of the species. Chromosome numbers are given for 91 populations representing all species, including the first reports for Arnica nevadensis. Results of apomixis, vegetative reproduction, breeding studies, and artifi• cial hybridizations are given. Interrelationships of insect pollinators, leaf miners, achene feeders, and floret feeders are presented. Arnica cordifolia, the ancestral species consists largely of tetraploid populations, which are either autonomous or pseudogamous apomicts, and to a lesser degree diploid, triploid, pentaploid, and hexaploid populations. -

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region Sensitive Plant Species by Forest

USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region 1 Sensitive Plant Species by Forest 2013 FS R5 RF Plant Species List Klamath NF Mendocino NF Shasta-Trinity NF NF Rivers Six Lassen NF Modoc NF Plumas NF EldoradoNF Inyo NF LTBMU Tahoe NF Sequoia NF Sierra NF Stanislaus NF Angeles NF Cleveland NF Los Padres NF San Bernardino NF Scientific Name (Common Name) Abies bracteata (Santa Lucia fir) X Abronia alpina (alpine sand verbena) X Abronia nana ssp. covillei (Coville's dwarf abronia) X X Abronia villosa var. aurita (chaparral sand verbena) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. abramsii (Abrams' flowery puncturebract) X X Acanthoscyphus parishii var. cienegensis (Cienega Seca flowery puncturebract) X Agrostis hooveri (Hoover's bentgrass) X Allium hickmanii (Hickman's onion) X Allium howellii var. clokeyi (Mt. Pinos onion) X Allium jepsonii (Jepson's onion) X X Allium marvinii (Yucaipa onion) X Allium tribracteatum (three-bracted onion) X X Allium yosemitense (Yosemite onion) X X Anisocarpus scabridus (scabrid alpine tarplant) X X X Antennaria marginata (white-margined everlasting) X Antirrhinum subcordatum (dimorphic snapdragon) X Arabis rigidissima var. demota (Carson Range rock cress) X X Arctostaphylos cruzensis (Arroyo de la Cruz manzanita) X Arctostaphylos edmundsii (Little Sur manzanita) X Arctostaphylos glandulosa ssp. gabrielensis (San Gabriel manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos hooveri (Hoover's manzanita) X Arctostaphylos luciana (Santa Lucia manzanita) X Arctostaphylos nissenana (Nissenan manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos obispoensis (Bishop manzanita) X Arctostphylos parryana subsp. tumescens (interior manzanita) X X Arctostaphylos pilosula (Santa Margarita manzanita) X Arctostaphylos rainbowensis (rainbow manzanita) X Arctostaphylos refugioensis (Refugio manzanita) X Arenaria lanuginosa ssp. saxosa (rock sandwort) X Astragalus anxius (Ash Valley milk-vetch) X Astragalus bernardinus (San Bernardino milk-vetch) X Astragalus bicristatus (crested milk-vetch) X X Pacific Southwest Region, Regional Forester's Sensitive Species List. -

Field Release of the Hoverfly Cheilosia Urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae)

USDA iiillllllllll United States Department of Field release of the hoverfly Agriculture Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Marketing and Regulatory Syrphidae) for biological Programs control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Field release of the hoverfly Cheilosia urbana (Diptera: Syrphidae) for biological control of invasive Pilosella species hawkweeds (Asteraceae) in the contiguous United States. Environmental Assessment, July 2019 Agency Contact: Colin D. Stewart, Assistant Director Pests, Pathogens, and Biocontrol Permits Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service U.S. Department of Agriculture 4700 River Rd., Unit 133 Riverdale, MD 20737 Non-Discrimination Policy The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination against its customers, employees, and applicants for employment on the bases of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex, gender identity, religion, reprisal, and where applicable, political beliefs, marital status, familial or parental status, sexual orientation, or all or part of an individual's income is derived from any public assistance program, or protected genetic information in employment or in any program or activity conducted or funded by the Department. (Not all prohibited bases will apply to all programs and/or employment activities.) To File an Employment Complaint If you wish to file an employment complaint, you must contact your agency's EEO Counselor (PDF) within 45 days of the date of the alleged discriminatory act, event, or in the case of a personnel action. Additional information can be found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_file.html. To File a Program Complaint If you wish to file a Civil Rights program complaint of discrimination, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form (PDF), found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html, or at any USDA office, or call (866) 632-9992 to request the form. -

Coyote Creek South Management Plan

Coyote Creek South Management Plan Photo credit: Philip Bayles Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife 4034 Fairiew Industrial Drive SE Salem, Oregon 97302 March 2016 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS The following individuals, mainly consisting of Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife biologists and program coordinators, provided valuable input into this plan: • Ann Kreager, Willamette Wildlife Mitigation Project Biologist, South Willamette Watershed, ODFW • Emily Steel, Restoration Ecologist, City of Eugene • Trevor Taylor, Natural Areas Restoration Team Supervisor, City of Eugene • Bruce Newhouse, Ecologist, Salix Associates • David Stroppel, Habitat Program Manager, South Willamette Watershed, ODFW • Wayne Morrow, Wildlife Manager, Fern Ridge Wildlife Area, ODFW • Kevin Roth, Wildlife Technician Senior, Fern Ridge Wildlife Area, ODFW In addition, the plan draws on the work of professional ecologists and planners, and feedback from a wide variety of representatives from ODFW and partner agencies, including: • Ed Alverson, Botanist • Diane Steeck, Wetland Ecologist, City of Eugene • Paul Gordon, Wetland Technical Specialist, City of Eugene • Steve Marx, SW Watershed District Manager, ODFW • Bernadette Graham-Hudson, Fish & Wildlife Operations and Policy Analyst, ODFW • Laura Tesler, Wildlife Wildlife Mitigation Staff Biologist, ODFW • Shawn Woods, Willamette Wildlife Mitigation Restoration Biologist, ODFW • Sue Beilke, Willamette Wildlife Mitigation Project Biologist, ODFW • Susan Barnes, NW Region Wildlife Diversity Biologist, ODFW • Keith Kohl,