Salmon Creek Estuary: Study Results and Enhancement Recommendations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project

APPENDIX D Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project An Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project Mendocino and Sonoma Counties, California Eileen Barrow, M.A. June 6, 2016 An Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project Mendocino and Sonoma Counties, California Prepared by: _________________________________ Eileen Barrow, M.A. Tom Origer & Associates Post Office Box 1531 Rohnert Park, California 94927 (707) 584-8200 Prepared for: Sonoma County Water Agency 404 Aviation Santa Rosa, California 95407 June 6, 2016 ABSTRACT Tom Origer & Associates conducted an archival study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project, as requested by the Sonoma County Water Agency. This study was designed to meet requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act. Per the findings of the National Marine Fisheries Service (2008), the Sonoma County Water Agency is seeking to improve Coho salmon and steelhead habitat in the Russian River and Dry Creek by modifying the minimum instream flow requirements specified by the State Water Resources Control Board's 1986 Decision 1610. The current study includes a ⅛ mile buffer around Lake Mendocino, Lake Sonoma, the Russian River from Coyote Valley Dam to the Pacific Ocean, and Dry Creek from Warm Springs Dam to the Russian River. The study included archival research at the Northwest Information Center, Sonoma State University (NWIC File No. 15-1481); archival research at the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley; examination of the library and files of Tom Origer & Associates; and contact with the Native American community. Documentation pertaining to this study is on file at the offices of Tom Origer & Associates (File No. -

Captain Stephen Smith

Captain Smith - 1 Captain Stephen Smith son of Giles Smith & Ruth Howland Captain Stephen Smith, born: 15 Dec 1788 Dartmouth Massachusetts, died: 18 Nov 1855 San Francisco California, married: Manuela Torres 1843 (she was born: 1828 Peru, died: 1871 San Francisco California, (children: Stephen Manuel 1843, Manuelita 1848, Juana 1848, Ruth 1860) Tomas 1838, William 1843 w/ Tsupu, James 1852 James Smith 1852- Captain Stephen Smith’s Adobe Captain Stephen Smith’s Bodega Hotel - 1852 Captain Smith - 2 Manuella Smith’s brother Captain Smith - 3 At Santa Cruz he took on lumber for the building of his mills. At San Francisco he took on James Hudspeth, Nathaniel Coombs, John Daubenbiss, (who later built a saw mill and a grist mill in Soquel, Santa Cruz) and Alexander Copeland. Captain Smith - 4 Captain Smith - 5 Captain Smith - 6 Captain Smith - 7 Captain Smith - 8 Captain Smith - 9 Captain Smith - 10 Captain Smith - 11 Captain Smith - 12 Captain Smith - 13 Will 19 Nov 1855 Captain Smith - 14 Captain Stephen Smith’s Will - 7 Aug 1854 Captain Smith - 15 Captain Smith - 16 Captain Smith - 17 Captain Smith - 18 Captain Smith - 19 Captain Smith - 20 Captain Smith - 21 Eleanor Smith 1st wife of Captain Stephen Smith Eleanor Smith, born: 1795 Maryland, died: 183? Maryland, married: Captain Stephen Smith 1810 Maryland, children: Elvira (Pond) 1810, Stephen Henry 1816, Ellen (Morison) 1819, Giles 1832 Giles Smith 1832- four Elvira Smith 1810, Stephen Henry Smith 1816, Ellen Smith 1819 & Giles Smith 1832 Captain Smith - 22 Giles Smith son of Captain Stephen Smith & Eleanor Smith Captain Smith - 23 Elvira (Smith) Pond daughter of Captain Stephen Smith & Eleanor Smith Rancho Blucher by Inheritance In 1854, Captain Stephen Smith granted in his will 1/2 league of land in the Rancho Blucher to each of his children with Eleanor; Elvira, Stephen Henry, Ellen & Giles. -

Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, Circa 1852-1904

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb109nb422 Online items available Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Finding Aid written by Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Documents BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM 1 Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in Cali... Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Michelle Morton and Marie Salta, with assistance from Dean C. Rowan and Randal Brandt. Date Completed: March 2008 © 2008, 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Documents pertaining to the adjudication of private land claims in California Date (inclusive): circa 1852-1904 Collection Number: BANC MSS Land Case Files 1852-1892 Microfilm: BANC MSS C-A 300 FILM Creators : United States. District Court (California) Extent: Number of containers: 857 Cases. 876 Portfolios. 6 volumes (linear feet: Approximately 75)Microfilm: 200 reels10 digital objects (1494 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: In 1851 the U.S. -

36 NEWT HOUGHTS on the K OSTROMITINOV R ANCH, SONOMAC OUNTY, CALIFORNIA Colony Ross, Or Fort Ross As It Is Known Today, Was a Me

36 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY FOR CALIFORNIA ARCHAEOLOGY, VOL. 19, 2006 NNNEWEWEW THOUGHTSHOUGHTSHOUGHTS ONONON THETHETHE KOSTROMITINOV RANCHANCHANCH, SS, ONOMAONOMAONOMA COUNTYOUNTYOUNTY, CC, ALIFORNIAALIFORNIAALIFORNIA TSIM D. SCHNEIDER Established in 1833, Kostromitinov Ranch was an outlying farming operation intended to supply Colony Ross and to support Russian- American Company (RAC) outposts along the Pacific Rim. Although its precise location is unknown and few ethnohistoric documents mention the operation, Kostromitinov Ranch continues to hold serious potential for culture -contact research. This paper discusses adjunct reconnaissance and survey carried out near Willow Creek during the 2004 summer field school at Fort Ross, archival and map research pertaining to Kostromitinov Ranch, and the possibilities for investigating colonial interactions on a multi-sided and fluid frontier. olony Ross, or Fort Ross as it is known today, was a mercantilist natives living around the Ross settlement it would have been impossible operation and outpost for the Russian-American Company (RAC) to harvest the crops because of a shortage of labor.” A deliberate Cfrom 1812 until 1841. The Ross Colony included the commercial strategy of the RAC thus involved recruitment of local administrative center of Ross, Port Rumianstev at Bodega Harbor, a natives. They could be paid less, required less upkeep, they were familiar hunting artel located on the Farralon Islands, and, later, at least three with extracting local resources such as sea otters, and they had farming or ranching operations located south of Ross (Lightfoot knowledge of local plants and animals that could supplement strained 2005:121). As the distant cornerstone of a once-extensive commercial colonial food resources. -

BLT Journal 2018 V1.4 FINAL.Pages

2018 JULY Journal For over 25 years “. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” . Aldo Leopold (1886-1948), American Forester SONOMA LAND TRUST DONATES GILCHRIST EASEMENT A Partnership for Land Protection along Coleman Valley Creek To ring in the new year, Bodega Land Trust received, from Sonoma Land Trust, a conservation easement over a beautiful quarter-mile stretch of Coleman Valley Creek west of Occi- dental (image shown is in the ease- ment). The creek, which runs across a property donated to Sonoma Land Trust in 2017, is a major tributary of Salmon Creek. The new easement is named after Alden Gilchrist, who loved the underlying property and whose partner generously donated the land to the Sonoma Land Trust after Alden’s death. The easement covers approximately 11 undeveloped acres of the 16-acre property. The creek adds about a half-mile of protected creek bank to our inventory in the Salmon Creek watershed. The easement includes Douglas fir, coast live oak, bay, a few redwoods and numerous native shrubs and grasses. Commercial timber harvest- ing is prohibited. Only firewood may be cut. All subdivision, new struc- tures “with roofs”, roads and cross fencing are prohibited. Coleman Valley Creek Photo by Akiva Zaslansky Coleman Valley Creek is a major priority for our land and water pro- tection work. This easement is espe- cially important to Bodega Land Trust because it is contiguous with our 68.6-acre Salmon Creek Headwaters easement, donated in 1998. We also hold a 200-foot wide riparian corri- dor easement on the west bank of the lower reach of the creek, donated in 2001. -

WRIGHT HILL RANCH OPEN SPACE PRESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN Natural and Cultural Resources JANUARY 2017

SONOMA COUNTY AGRICULTURAL PRESERVATION & OPEN SPACE DISTRICT WRIGHT HILL RANCH OPEN SPACE PRESERVE MANAGEMENT PLAN Natural and Cultural Resources JANUARY 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Regional Planning Context ..........................................................................................................................1 1.2 Purpose and Goals ........................................................................................................................................2 1.3 Development Process .................................................................................................................................2 1.3.1 Document Development .................................................................................................................2 1.3.2 Technical Experts and Stakeholder Group Engagement .................................................3 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................................4 2.1 Location and Regional Setting ................................................................................................................4 2.2 Adjacent Ownership and Land Uses ...................................................................................................4 2.3 Historic Land Uses of Wright Hill Ranch and Surrounding Areas .........................................4 -

The Future's Not What It Used to Be: the Decline of Technological Enthusiasm in America, 1957-1970 Lester Louis Poehner Jr

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 The future's not what it used to be: the decline of technological enthusiasm in America, 1957-1970 Lester Louis Poehner Jr. Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Studies Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Poehner, Lester Louis Jr., "The future's not what it used to be: the decline of technological enthusiasm in America, 1957-1970 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12385. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12385 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Sonoma County's Landscape and Horticultural History

Journal of the California Garden & Landscape History Society Vol. 15 No. 3 • Summer 2012 Sonoma County’s Landscape and Horticultural History Thomas A. Brown he land in what is now Sonoma County was initially caught by the Aleuts who had come with them. (The Cali- T home to Native Americans, with their principal tribes fornia poppy, the state flower, acquired its botanical name, the Pomo, Wappo, and Miwok. Like other California Indi- Eschscholzia californica, from a visiting Russian natural- ans living in terrains with mild climates and generous vege- ist.) When the Russians’ farming efforts proved insuffi- tation, they practiced neither horticulture (cultivating plants cient, they sent ships down to the San Francisco presidio, for special purposes, including ornamental ones) nor agri- where wheat, tallow, and dried or brined beef produced by culture (growing groups of plants systematically, mostly for the northern missions could be purchased and paid for in use as food crops or as for- pelts, various articles age for livestock). They re- crafted by the Russians lied greatly on local plants, (including small boats), not only for food but also to and—when absolutely nec- supply many other practical essary—coin. Neither side needs. Wild animals, shell- adhered to the Spanish edict fish, and salmon provided forbidding all trade with most of their dietary protein. foreigners. Spain, em- As hunter-gatherers the na- broiled in the war of Mexi- tives made little impact upon can Independence, could the landscape, though they spare neither men nor re- practiced a few simple land- sources to prevent this traf- management tactics such as fic or to dislodge the Rus- protecting the sedges used in The probable appearance of Mission San Francisco Solano in Sonoma, sians. -

Fort Ross & Salt Point News March 2012

Having trouble viewing this email? Click here Fort Ross & Salt Point News March 2012 Fort Ross Interpretive Association A California State Park Cooperating Association ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Fort Ross, Common Ground Bicentennial Conference We are honored to have statements from both His Excellency Ambassador Sergey Kislyak, and the Honorable Ambassador Michael McFaul, addressing the Fort Ross bicentennial. CONTACT INFORMATION Two hundred years ago Russian settlers came to this Fort Ross Interpretive Association faraway land guided by their aspiration to serve the economic and political good of their motherland. Their presence had a significant impact on the history of California ... But what is more important, Russian settlers came in peace and were good neighbors to Kashaya, Pomo, Miwok, Spaniards, Mexicans, and Americans. Two hundred years ago they established what we call today good neighborly relations with the peoples of this land. Since that time Russia and the U.S. went through different periods in their bilateral relations. There were many ups and downs in our history. But Fort Ross will always be remembered as one of the most remarkable and successful stories of our relationship. Let me express sincere gratitude to all who help maintain and preserve Fort Ross, and wish you every success in this noble cause. -- Sergey Kislyak, Ambassador of the Russian Federation to the United States "I am pleased to join the many Americans and Russians who will celebrate the 200th Anniversary of the founding of Fort Ross this year... The history of what the Russian-American Company did at Fort Ross, and what succeeding generations of Russians and Americans have done to preserve it, will be discussed and celebrated -- and rightly so. -

Geology, Technology and Policy: Finding Faults and Moving Forward with Nuclear Power and Waste Disposal

Geology, Technology and Policy: Finding Faults and Moving Forward with Nuclear Power and Waste Disposal Caitlin Lippincott Science, Technology and Society Department Franklin and Marshall College Lancaster, Pennsylvania STS 490 - Independent Study: Honors Thesis Dr. James Strick, Advisor 29 April 2005 Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1: The Political History of the U.S. High Level Waste Repository……...2 Postscript…………………………………………………………………23 Chapter 2: The Geologic Debate over High Level Waste Repositories………….27 Survey of Other Nations………………………………………………….36 Chapter 3: Earthquake Hazards and Public Opinion……………………………..46 Earthquake Hazard: Finding Fault………………………………………..46 Bodega Bay……………………………………………………………….50 Diablo Canyon……………………………………………………………55 Evacuation Problems……………………………………………………..58 Chapter 4: The South Korea Case………………………………………………..63 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………..72 Appendix: Quick Outline to Nuclear Energy and Waste Disposal………………74 Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………...80 1 Introduction This project began in South Korea, when two geologists, Uechan Chwae and Sung-ja Choi, asked me if they could suggest a topic for my senior thesis. They were interested in knowing the history that lies behind the United States’s siting strategies for nuclear power plants and for its proposed waste disposal site. From that moment the project took off and expanded into the following thesis. I decided to explore the political side of many case studies as well as the geology since the outcomes were often clearly related to both aspects. I attempted to unravel the often very complicated network of agencies involved in the U.S. nuclear program, relying heavily on personal interviews. I also tried to touch on other countries with prominent nuclear programs. With over fifty years of nuclear power history the U.S. -

Maps of Private Land Grant Cases of California, [Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/hb8489p15p Online items available Finding Aid to the Maps of Private Land Grant Cases of California, [ca. 1840-ca. 1892] Finding aid written by Mary W. Elings Funding for processing this collection was provided by the University of California Library. The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected]/ URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu © 2004 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Maps of LAND CASE MAP 1 Private Land Grant Cases of California, [ca. 1840-ca. 1892] Finding Aid to the Maps of Private Land Grant Cases of California, [ca. 1840-ca. 1892] Collection number: LAND CASE MAP The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected]/ URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Funding for processing this collection was provided by the University of California Library. Finding Aid Author(s): Finding aid written by Mary W. Elings Date Completed: December 2004 Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Maps of private land grant cases of California Date (inclusive): [ca. 1840-ca. 1892] Collection Number: LAND CASE MAP Creator: United States. District Court (California) Extent: ca. 1,450 ms. maps : some hand col.1396 digital objects (1862 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected]/ URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu Abstract: Placed on permanent deposit in The Bancroft Library by the U.S. -

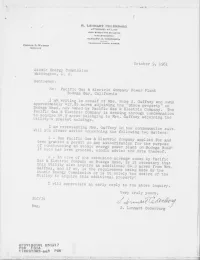

Requests Advice Concerning Util Application for Authorization Of

' "' ' a .- .d < /. 4m . ~, i ' .v/ .u : ~ :. A _: .o . J A'._*.s . 1 5 % 4 1 .- . 2.L J. ~. o ^ k . ' , , * * 8. LENNART CELERDORO A1TORNEY AT LAW SOOM SYNDif 4TE SUH.,OING '4 40 5'tOADWAr OAKtAND $2. CA12Polt,NIA TaLape.ooes H8eAvs 4-dese DIXON In WATSON .o. ,s . October 9, 1961 Atomic Energy Commission Washington, D. C. Gentlemen: Re: Pacific Gas & Electric Gompany Power Plant Bodega Bay, California | I am writing in behalf of Mrs. Rose S. Gaffney who owns approximately 437.85 acres adjoining the "Strow property" on Bodega Head, now owned by Pacific' Gas & Electric Company. The Pacific Gas & Electric Company is seeking through condemnation , ' Utility'sto acquire present 64.9 acres holdings. belonging to Mrs. Gaffney adjoining the I am representing Mrs. Gaffney in the condemnation suit. Will you please advise concerning the following two matters : 1 - Has Pacific Gas & Electric Company applied for and | been granted a permit or any. authorization for the purpose of constructing an atomic energy power plant on Bodega Head? , If such has been granted, kindly advise the date thereof. t 2 - In view of the extensive acreage owned by Pacific | ' Gas & Electric Company on Bodega Head, is it necessary that | | this Utility also acquire an additional 64.9 acres from Mrs. Gaffney, and if so, is the requirement being made by the Atomic Energy Commission or is it solely the desire of the Utility to acquire this additional property? I will appreciate an early reply to the above inquiry. Very truly yours, SLC/36 g /pth( ' | Reg. S.