Sonoma County's Landscape and Horticultural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy Star Qualified Buildings

1 ENERGY STAR® Qualified Buildings As of 1-1-03 Building Address City State Alabama 10044 3535 Colonnade Parkway Birmingham AL Bellsouth City Center 600 N 19th St. Birmingham AL Arkansas 598 John L. McClellan Memorial Veterans Hospital 4300 West 7th Street Little Rock AR Arizona 24th at Camelback 2375 E Camelback Phoenix AZ Phoenix Federal Courthouse -AZ0052ZZ 230 N. First Ave. Phoenix AZ 649 N. Arizona VA Health Care System - Prescott 500 Highway 89 North Prescott AZ America West Airlines Corporate Headquarters 111 W. Rio Salado Pkwy. Tempe AZ Tempe, AZ - Branch 83 2032 West Fourth Street Tempe AZ 678 Southern Arizona VA Health Care System-Tucson 3601 South 6th Avenue Tucson AZ Federal Building 300 West Congress Tucson AZ Holualoa Centre East 7810-7840 East Broadway Tucson AZ Holualoa Corporate Center 7750 East Broadway Tucson AZ Thomas O' Price Service Center Building #1 4004 S. Park Ave. Tucson AZ California Agoura Westlake 31355 31355 Oak Crest Drive Agoura CA Agoura Westlake 31365 31365 Oak Crest Drive Agoura CA Agoura Westlake 4373 4373 Park Terrace Dr Agoura CA Stadium Centre 2099 S. State College Anaheim CA Team Disney Anaheim 700 West Ball Road Anaheim CA Anahiem City Centre 222 S Harbor Blvd. Anahiem CA 91 Freeway Business Center 17100 Poineer Blvd. Artesia CA California Twin Towers 4900 California Ave. Bakersfield CA Parkway Center 4200 Truxton Bakersfield CA Building 69 1 Cyclotron Rd. Berkeley CA 120 Spalding 120 Spalding Dr. Beverly Hills CA 8383 Wilshire 8383 Wilshire Blvd. Beverly Hills CA 9100 9100 Wilshire Blvd. Beverly Hills CA 9665 Wilshire 9665 Wilshire Blvd. -

Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project

APPENDIX D Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project An Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project Mendocino and Sonoma Counties, California Eileen Barrow, M.A. June 6, 2016 An Archival Study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project Mendocino and Sonoma Counties, California Prepared by: _________________________________ Eileen Barrow, M.A. Tom Origer & Associates Post Office Box 1531 Rohnert Park, California 94927 (707) 584-8200 Prepared for: Sonoma County Water Agency 404 Aviation Santa Rosa, California 95407 June 6, 2016 ABSTRACT Tom Origer & Associates conducted an archival study for the Fish Habitat Flows and Water Rights Project, as requested by the Sonoma County Water Agency. This study was designed to meet requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act. Per the findings of the National Marine Fisheries Service (2008), the Sonoma County Water Agency is seeking to improve Coho salmon and steelhead habitat in the Russian River and Dry Creek by modifying the minimum instream flow requirements specified by the State Water Resources Control Board's 1986 Decision 1610. The current study includes a ⅛ mile buffer around Lake Mendocino, Lake Sonoma, the Russian River from Coyote Valley Dam to the Pacific Ocean, and Dry Creek from Warm Springs Dam to the Russian River. The study included archival research at the Northwest Information Center, Sonoma State University (NWIC File No. 15-1481); archival research at the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley; examination of the library and files of Tom Origer & Associates; and contact with the Native American community. Documentation pertaining to this study is on file at the offices of Tom Origer & Associates (File No. -

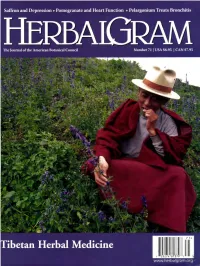

ADVISORY BOARDS Each Issue of Herbaigram Is Peer Reviewed by Various Members of Our Advisory Boards Prior to Publication

ADVISORY BOARDS Each issue of HerbaiGram is peer reviewed by various members of our Advisory Boards prior to publication . American Botanical Council Herb Research Dennis V. C. Awang, Ph.D., F.C.I.C., MediPiont Natural Gail B. Mahadr, Ph.D., Research Assistant Professor, Products Consul~ng Services, Ottowa, Ontario, Conodo Deportment o Medical Chemistry &Pharmacognosy, College of Foundation Pharmacy, University of Illinois, Chicago, Illinois Manuel F. Balandrin, R.Ph., Ph.D., Research Scien~st, NPS Rob McCaleb, President Pharmaceuticals, Salt LakeCity , Utah Robin J. Maries, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Botany, Brandon University, Brandon, Manitoba, Conodo Mi(hael J. Balidt, Ph.D., Director of the lns~tute of Econom ic Glenn Appelt, Ph.D., R.Ph., Author and Profess or Botany, the New York Botanical Gorden, Bronx, New York Dennis J. M(Kenna, Ph.D., Consulting Ethnophormocologist, Emeritus, University of Colorado, and with Boulder Beach Joseph M. Betz, Ph.D., Research Chemist, Center for Food Minneapolis, Minnesota Consulting Group Safety and Applied Nutri~on, Division of Natural Products, Food Daniel E. Moerman, Ph.D., William E. Stirton Professor of John A. Beutler, Ph.D., Natural Products Chemist, and Drug Administro~on , Washington, D.C. Anthropology, University of Michigon/ Deorbom, Dearborn, Michigan Notional Cancer Institute Donald J. Brown, N.D., Director, Natural Products Research Consultants; Faculty, Bastyr University, Seattle, Washington Samuel W. Page, Ph.D., Director, Division of Natural Products, Robert A. Bye, Jr., Ph.D., Professor of Ethnobotony, Notional University of Mexico Thomas J. Carlson, M.S., M.D., Senior Director, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutri~on , Food and Drug Administro~on , Washington, D.C. -

Salmon Creek Estuary: Study Results and Enhancement Recommendations

Salmon Creek Estuary: Study Results and Enhancement Recommendations Appendices Appendix A: Salmon Creek Oral History Project Appendix B: Water Quality Figures Salmon Creek Estuary: Study Results and Enhancement Recommendations – Appendices June 2006 Appendix A: Salmon Creek History and Oral History Summary (Prepared by Kathleen Harrison) I. The Original Human Residents of Salmon Creek Watershed The human history of the Salmon Creek watershed must, of course, reach back to the original, indigenous people who were here long before the current era. It is established that Native Americans have been moving through and settling in California for at the very least 12,000 years. Archeological signs of ongoing habitation here in Salmon Creek watershed extend back at least 8,000 years. We know that the natives of this region were adept hunters, gatherers and managers of natural resources. The people of this region of North America did not practice agriculture, but they tended naturally existing populations of plants, trees, and terrestrial and aquatic animal life. Their goals for successful management were to maximize production of the foods and materials useful to humans, maintain a healthy balance in diverse communities of flora and fauna, support the natural cycles and longevity of wild populations, and to honor the many forces that they recognized in nature. They did this with various documented methods of land management. Annual or periodic late-season burning effectively removed brush without killing established trees, prevented the accumulation of detritus that encourages bacterial, viral and fungal diseases in trees, and fertilized the soil with ash, encouraging growth and production of seeds and acorns. -

Phoenix Family and Nurseries Collection

McLean County Museum of History Phoenix Family and Nurseries Collection Processed by Tim Fuertges Summer 1997 Reprocessed by Torii Moré Summer 2010 Collection Information VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 2 Boxes COLLECTION DATES: 1823-1999 RESTRICTIONS: None REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History ALTERNATIVE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None LOCATION: Archives NOTES: Additional collections: Curatorial Department: Accession # 1997.003 (Hand- colored lithographs) Archive Photographs: under “Phoenix Nursery Photographs” Booklet “Gifts to the Prairie” by Daryl Watson available for sale in gift shop, $10 Brief History Franklin Kelsey Phoenix was born in 1823 in the small village of Perry, New York. At the age of twelve, Phoenix moved with his family to Delavan, Wisconsin. Delavan was a new town founded in a region that was largely wilderness, and Phoenix grew up “loving flowers, trees, and all nature.” In 1842 Phoenix started his life-long profession as a nurseryman in Delavan. He was a very passionate and energetic in his work, quickly becoming a respected voice in America’s horticultural community in his twenties. In the 1850s the nursery industry grew. F.K. Phoenix was an active participant in the Illinois Horticultural Society, and eventually relocated his business to Bloomington Illinois. By 1867 Phoenix’s nursery was 240 acres with six greenhouses. It grew “Fruit, Ornamental & Nursery Stock, Flowers, Bulbs, Greenhouse and Garden Plants” with “Grapes & Roses A Specialty.” His was the largest nursery in the “West” and one of the largest in the country. He also saw the value in colorful nursery plates, wildly colored images of trees, fruits, and flowers, which were used to advertise and expand his business. -

Woodstock Typewriter R

SUFFRAGISTE CERTAIN A Voter's Catechism OF DEMOCRATS' HELP D. Have you read the Consti- R. 435. Accordili» to the pop- -1 tution of the United States? ulation one to every 211,000, (the R. Yes. ratio fìxed by Congress Have after eack Leaders Resent Efforts to D. What form of Government deeennial eensus.) Them Support Hughes. The Woodstock is this? D. Which is the capital of the R. Republic. state of Pennsylvania. WON BY WILSON'S SPEECH. D. What is the Constitution of R. Harrisburg. Sileni Visible TYPEWIRTER the United States? D. How manv Senators has R. It is the fundamental law of u ì Have Come Here to Fight WITH each state in the United States You," He Telia National Convention this country. Senate? "Wilson Voteci For Suffrago; Ha» No Money in Advance D. Who makes the laws of the R. Two. Hughes?' Mrs. Graham of Idaho United Asks. States? D. Who are our U. S. Senators T SIOO Machines for Only R. The Congress. "Western women who have had the R. Boise Penrose and Georg® ballot equally with the men for several D. What does Congress consist T. Oliver. years resent the lnterferenee of one of of? suffraglsts D. For how long are they elect- the factions of and the at- Rep- tempt to turn the suffrage cause into R. Senate and House of ed? an adjunct of the Republican party. resentatives. R. 2 years. They believe they know how to vote, D. Who is our State Senator? they to turn against the $59.50 and refuse D. -

Unit 5 Ex-Situ Conservation

UNIT 2 EX-SITU CONSERVATION Structure 5.0 Introduction 5.1 Advantage of Ex-situ Conservation 5.2 Objectives 5.3 Ex-situ Conservation : Principles & Practices 5.4 Conventional methods of ex-situ conservation 5.4.1 Gene Bank 5.4.2 Community Seed Bank 5.4.3 Seed Bank 5.4.4 Botanical Garden 5.4.5 Field Gene Bank 5.5 Biotechnological methods of ex-situ conservation 5.4.1 In-vitro Conservation 5.4.2 In-vitro storage of germplasm and cryopreservation 5.4.3 Other method 5.4.4 Germplasm facilities in India 5.6 General Account of Important Institutions 5.4.1 BSI 5.4.2 NBPGR 5.4.3 IARI 5.4.4 SCIR 5.4.5 DBT 5.7 Let us sum up 5.8 Check your progress & the key 5.9 Assignments/ Activities 5.10 References/ Further Reading 44 5.0 INTRODUCTION For much of the time man lived in a hunter-gather society and thus depended entirely on biodiversity for sustenance. But, with the increased dependence on agriculture and industrialisation, the emphasis on biodiversity has decreased. Indeed, the biodiversity, in wild and domesticated forms, is the sources for most of humanity food, medicine, clothing and housing, much of the cultural diversity and most of the intellectual and spiritual inspiration. It is, without doubt, the very basis of life. Further that, a quarter of the earth‟s total biological diversity amounting to a million species, which might be useful to mankind in one way or other, is in serious risk of extinction over the next 2-3 decades. -

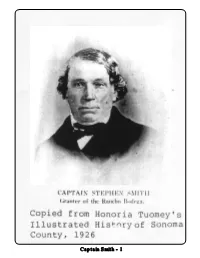

Captain Stephen Smith

Captain Smith - 1 Captain Stephen Smith son of Giles Smith & Ruth Howland Captain Stephen Smith, born: 15 Dec 1788 Dartmouth Massachusetts, died: 18 Nov 1855 San Francisco California, married: Manuela Torres 1843 (she was born: 1828 Peru, died: 1871 San Francisco California, (children: Stephen Manuel 1843, Manuelita 1848, Juana 1848, Ruth 1860) Tomas 1838, William 1843 w/ Tsupu, James 1852 James Smith 1852- Captain Stephen Smith’s Adobe Captain Stephen Smith’s Bodega Hotel - 1852 Captain Smith - 2 Manuella Smith’s brother Captain Smith - 3 At Santa Cruz he took on lumber for the building of his mills. At San Francisco he took on James Hudspeth, Nathaniel Coombs, John Daubenbiss, (who later built a saw mill and a grist mill in Soquel, Santa Cruz) and Alexander Copeland. Captain Smith - 4 Captain Smith - 5 Captain Smith - 6 Captain Smith - 7 Captain Smith - 8 Captain Smith - 9 Captain Smith - 10 Captain Smith - 11 Captain Smith - 12 Captain Smith - 13 Will 19 Nov 1855 Captain Smith - 14 Captain Stephen Smith’s Will - 7 Aug 1854 Captain Smith - 15 Captain Smith - 16 Captain Smith - 17 Captain Smith - 18 Captain Smith - 19 Captain Smith - 20 Captain Smith - 21 Eleanor Smith 1st wife of Captain Stephen Smith Eleanor Smith, born: 1795 Maryland, died: 183? Maryland, married: Captain Stephen Smith 1810 Maryland, children: Elvira (Pond) 1810, Stephen Henry 1816, Ellen (Morison) 1819, Giles 1832 Giles Smith 1832- four Elvira Smith 1810, Stephen Henry Smith 1816, Ellen Smith 1819 & Giles Smith 1832 Captain Smith - 22 Giles Smith son of Captain Stephen Smith & Eleanor Smith Captain Smith - 23 Elvira (Smith) Pond daughter of Captain Stephen Smith & Eleanor Smith Rancho Blucher by Inheritance In 1854, Captain Stephen Smith granted in his will 1/2 league of land in the Rancho Blucher to each of his children with Eleanor; Elvira, Stephen Henry, Ellen & Giles. -

What to Expect on Your Visit

WEISER RAILROAD Firestone Station FORD ROUGE FACTORY TOUR Susquehanna Platform Smiths Creek Platform RAILROAD JUNCTION C 15 16 WHAT TO EXPECT 7 LIBERTY CRAFTWORKS 6 MAIN STREET 19 90 Junction Street34 ON YOUR VISIT Christi 20 38 13 22 e St r Detroit State Street ee WORKING FARMS 24 Central t Market 11 Wa sh Su WELCOME to Greenfield MAP KEY i w ngton Blvd Firestone Lane reet anee L Village. This guide is to help Post St 44 anding Tickets and Membership . ain Street you navigate our village while Bagle M 45 52 y A 83 Mill Road 47 following the new guidelines v 94 Restrooms e. 56 84 Michigan State Street 27 55 Av for a safe and enjoyable visit. wheelchair accessible Maple La e. except as noted Ford Road 57 enter 4 C A Quiet room available. Please see 25 59 Chr ne 86 Benson Ford 3 5 is tie a Guest Services Associate. Research S 2 tr 87 HENRY FORD’S MODEL T ee t Family Restroom 79 GOOD TO KNOW 1 60 Walnut Grove 98 61 Burbank Lane Ride Tickets TICKETS + PARKING LOT Field MASKS AND GUEST SERVICES EDISON AT WORK 63 FACE COVERINGS 75 Face masks are Train Stop required in all indoor A - Firestone Station B - Susquehanna Station e spaces, as well as an C -Smiths Creek L during the ticketing and Grove 73 admission process for STAFFED EXPERIENCES SELF-GUIDED EXPERIENCES all venues, or anytime Dining social distancing PORCHES AND PARLORS Maple Lane96 cannot be maintained. Shopping 6 Firestone Farm 4 Soybean Lab Agriculture 72 Cotswold Forge B 13 Pottery Shop Gallery 73 Giddings Family Home 68 WASH YOUR HANDS 5 Richart Carriage Shop (first floor only) 20 Glass Shop 72 Keep the health of all 69 25 Henry Ford Birthplace 7 Cider Mill 75 Robert Frost Home guests in mind. -

(247) U. C. Berkeley Botanical Garden: Edition of 1306 of Which 250 Copies Are Signed 1-250, 27 Copies Are Signed A-Zz As Artist

(247) U. C. Berkeley Botanical Garden: Edition of 1306 of which 250 copies are signed 1-250, 27 copies are signed A-Zz as artist’s proofs, 4 are signed as dedication copies. Three sets of progressives. March 28, 2019 17-7/16” x 24" Fifteen Colors Paper: Finch Fine Cover Ultra-smooth 100 pound Client: University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley 1-125: Saint Hieronymus Press 126-250: U. C. Botanical Garden Progressives: U. C. Botanical Garden A-Zz: Artist’s own use Dedication copies: Shari Bashin-Sullivan; Mariela Gerstein; Katherine Greenberg; Claire Nicole Stremple A number of scientists (Jagadish Chandra Bose, Daniel Chamovitz, Steve Sillett, Monica Gagliano, inter alia) have advanced persuasive arguments that, so far from being at Aristotle’s bottom of the ladder of life, plants actually lead rich and varied existences, fairly wallowing in an unsuspected paradise of sensuality. They can smell, they can communicate, they demonstrate short term, immune and transgenerational memory; they also demonstrate emotions. They just don’t show these things the way we do, primarily, of course, because we didn’t think to look. Or maybe we just didn’t listen: Luther Burbank and George Washington Carver both reputedly talked, and listened to, the plants with which they did their work. “Darwin, one of the great plant researchers, proposed what has become known as the “root-brain” hypothesis. Darwin proposed that the tip of the root, the part that we call the meristem, acts like the brain does in lower animals, receiving sensory input and directing movement. Several modern-day research groups are following up on this line of research.” —Daniel Chamovitz, Scientific American June 5, 2012 The distinction between plant and animal is blurred with the Venus Flytrap, which not only reacts to living prey as would an animal, but can actually count. -

Hops Humulus Lupulus L

HERB PROFILE Hops Humulus lupulus L. Family: Cannabaceae INTRODUCTION as noted from observations of young women who reportedly often ops is a perennial vine growing vertically to 33 feet experienced early menstrual periods after harvesting the strobiles with dark green, heart-shaped leaves.l,2,3 The male and in hops fields. lB H female flowers grow on separate vines.l.3 Hops are the Traditionally hops were used for nervousness, insomnia, excit dried yellowish-green, cone-like female flowers or fruits (tech ability, ulcers, indigestion, and restlessness associated with tension nically referred to as strobiles).l.4 Originally native to Europe, headache.l3 Additional folk medicine uses include pain relief, Asia, and North America,5 several varieties of hops are now culti improved appetite, and as a tonic.9 A tea made of hops was vated in Germany, the United States, the British Isles, the Czech ingested for inflammation of the bladder.? Native American Republic, South America, and Australia.4,6 Although still wild tribes used hops for insomnia and pain.5,8 Hops are employed in in Europe and North America, commercial hops come exclu Ayurvedic (Indian) medicine for restlessness and in traditional sively from cultivated plants.1,7 The leaves, shoots, female flowers C hinese medicine for insomnia, stomach upset and cramping, (hops), and oil are the parts of the plant used commercially. 8 and lack of appetite.5 Clinical studies in China report promise for the treatment of tuberculosis, leprosy, acute bacterial dysen HISTORY AND CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE -

History and Current Status of Systematic Research with Araceae

HISTORY AND CURRENT STATUS OF SYSTEMATIC RESEARCH WITH ARACEAE Thomas B. Croat Missouri Botanical Garden P. O. Box 299 St. Louis, MO 63166 U.S.A. Note: This paper, originally published in Aroideana Vol. 21, pp. 26–145 in 1998, is periodically updated onto the IAS web page with current additions. Any mistakes, proposed changes, or new publications that deal with the systematics of Araceae should be brought to my attention. Mail to me at the address listed above, or e-mail me at [email protected]. Last revised November 2004 INTRODUCTION The history of systematic work with Araceae has been previously covered by Nicolson (1987b), and was the subject of a chapter in the Genera of Araceae by Mayo, Bogner & Boyce (1997) and in Curtis's Botanical Magazine new series (Mayo et al., 1995). In addition to covering many of the principal players in the field of aroid research, Nicolson's paper dealt with the evolution of family concepts and gave a comparison of the then current modern systems of classification. The papers by Mayo, Bogner and Boyce were more comprehensive in scope than that of Nicolson, but still did not cover in great detail many of the participants in Araceae research. In contrast, this paper will cover all systematic and floristic work that deals with Araceae, which is known to me. It will not, in general, deal with agronomic papers on Araceae such as the rich literature on taro and its cultivation, nor will it deal with smaller papers of a technical nature or those dealing with pollination biology.