Political Rhetoric and Publicity in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Prime Ministers of Estonia

SNo Name Took office Left office Political party 1 Konstantin Päts 24-02 1918 26-11 1918 Rural League 2 Konstantin Päts 26-11 1918 08-05 1919 Rural League 3 Otto August Strandman 08-05 1919 18-11 1919 Estonian Labour Party 4 Jaan Tõnisson 18-11 1919 28-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 5 Ado Birk 28-07 1920 30-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 6 Jaan Tõnisson 30-07 1920 26-10 1920 Estonian People's Party 7 Ants Piip 26-10 1920 25-01 1921 Estonian Labour Party 8 Konstantin Päts 25-01 1921 21-11 1922 Farmers' Assemblies 9 Juhan Kukk 21-11 1922 02-08 1923 Estonian Labour Party 10 Konstantin Päts 02-08 1923 26-03 1924 Farmers' Assemblies 11 Friedrich Karl Akel 26-03 1924 16-12 1924 Christian People's Party 12 Jüri Jaakson 16-12 1924 15-12 1925 Estonian People's Party 13 Jaan Teemant 15-12 1925 23-07 1926 Farmers' Assemblies 14 Jaan Teemant 23-07 1926 04-03 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 15 Jaan Teemant 04-03 1927 09-12 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 16 Jaan Tõnisson 09-12 1927 04-121928 Estonian People's Party 17 August Rei 04-121928 09-07 1929 Estonian Socialist Workers' Party 18 Otto August Strandman 09-07 1929 12-02 1931 Estonian Labour Party 19 Konstantin Päts 12-02 1931 19-02 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 20 Jaan Teemant 19-02 1932 19-07 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 21 Karl August Einbund 19-07 1932 01-11 1932 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 22 Konstantin Päts 01-11 1932 18-05 1933 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 23 Jaan Tõnisson 18-05 1933 21-10 1933 National Centre Party 24 Konstantin Päts 21-10 1933 24-01 1934 Non-party 25 Konstantin Päts 24-01 1934 -

Tartu Kuvand Reisisihtkohana Kohalike Ja Välismaiste Turismiekspertide Seas

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at Tartu University Library Tartu Ülikool Sotsiaalteaduskond Ajakirjanduse ja kommunikatsiooni instituut Tartu kuvand reisisihtkohana kohalike ja välismaiste turismiekspertide seas Bakalaureusetöö (4 AP) Autor: Maarja Ojamaa Juhendaja: Margit Keller, PhD Tartu 2009 Sisukord Sissejuhatus ..................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Töö teoreetilised ja empiirilised lähtekohad ............................................................................ 7 1.1. Turism .................................................................................................................................. 7 1.2. Reisisihtkoha maine ja selle tekkimine ............................................................................ 9 1.2.1. Võimalikud takistused positiivse maine kujunemisel ............................................. 11 1.3. Sihtkoha bränd ja brändimine ........................................................................................ 12 1.4. Teised uuringud sarnastel teemadel ............................................................................... 15 1.5. Uuringu objekt: Tartu reisisihtkohana ............................................................................ 16 1.5.1. Turismistatistika Eestis ja Tartus ............................................................................ 17 2. Uurimisküsimused ................................................................................................................ -

Challenges Facing Estonian Economy in the European Union

Vahur Kraft: Challenges facing Estonian economy in the European Union Speech by Mr Vahur Kraft, Governor of the Bank of Estonia, at the Roundtable “Has social market economy a future?”, organised by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Tallinn, 19 August 2002. * * * A. Introduction, review of the early 1990s and comparison with the present day First of all, allow me to thank Konrad Adenauer Foundation for the organisation of this interesting roundtable and for the honourable invitation to speak about “Challenges of Estonian economy in the European Union”. Today’s event shows yet again how serious is the respected organisers’ interest towards the EU applicant countries. I personally appreciate highly your support to our reforms and convergence in the society and economy. From the outside it may seem that the transformation and convergence process in Estonia has been easy and smooth, but against this background there still exist numerous hidden problems. One should not forget that for two generations half of Europe was deprived of civil society, private ownership, market economy. This is truth and it has to be reckoned with. It is also clear that the reflections of the “shadows of the past” can still be observed. They are of different kind. If people want the state to ensure their well-being but are reluctant to take themselves any responsibility for their own future, it is the effect of the shadows of the past. If people are reluctant to pay taxes but demand social security and good roads, it is the shadow of the past. In brief, if people do not understand why elections are held and what is the state’s role, it is the shadow of the past. -

Culture and Sports

2003 PILK PEEGLISSE • GLANCE AT THE MIRROR Kultuur ja sport Culture and Sports IMEPÄRANE EESTI MUUSIKA AMAZING ESTONIAN MUSIC Millist imepärast mõju avaldab soome-ugri What marvellous influence does the Finno-Ugric keelkond selle kõnelejate muusikaandele? language family have on the musical talent of Selles väikeses perekonnas on märkimisväär- their speakers? In this small family, Hungarians seid saavutusi juba ungarlastel ja soomlastel. and Finns have already made significant achieve- Ka mikroskoopilise Eesti muusikaline produk- ments. Also the microscopic Estonia stuns with its tiivsus on lausa harukordne. musical productivity. Erkki-Sven Tüür on vaid üks neist Tallinnast Erkki-Sven Tüür is only one of those voices coming tulevatest häältest, kellest kõige kuulsamaks from Tallinn, the most famous of whom is regarded võib pidada Arvo Pärti. Dirigent, kes Tüüri to be Arvo Pärt. The conductor of the Birmingham symphony orchestra who performed on Tüür's plaadil "Exodus" juhatab Birminghami süm- record "Exodus" is his compatriot Paavo Järvi, fooniaorkestrit, on nende kaasmaalane Paavo regarded as one of the most promising conductors. Järvi, keda peetakse üheks paljulubavamaks (Libération, 17.10) dirigendiks. (Libération, 17.10) "People often talk about us as being calm and cold. "Meist räägitakse tavaliselt, et oleme rahulik ja This is not so. There is just a different kind of fire külm rahvas. See ei vasta tõele. Meis põleb teist- burning in us," decleares Paavo Järvi, the new sugune tuli," ütles Bremeni Kammerfilharmoo- conductor of the Bremen Chamber Philharmonic. nia uus dirigent Paavo Järvi. Tõepoolest, Paavo Indeed, Paavo Järvi charmed the audience with Järvi võlus publikut ettevaatlike käeliigutuste, careful hand gestures, mimic sprinkled with winks silmapilgutusterohke miimika ja hiljem temaga and with a dry sense of humour, which became vesteldes avaldunud kuiva huumoriga. -

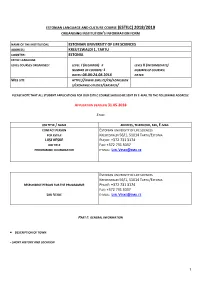

1 Estonian University of Life Sciences Kreutzwaldi 1

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE COURSE (ESTILC) 2018/2019 ORGANISING INSTITUTION ’S INFORMATION FORM NAME OF THE INSTITUTION : ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES ADDRESS : KREUTZWALDI 1, TARTU COUNTRY : ESTONIA ESTILC LANGUAGE LEVEL COURSES ORGANISED: LEVEL I (BEGINNER ) X LEVEL II (INTERMEDIATE ) NUMBER OF COURSES : 1 NUMBER OF COURSES : DATES : 08.08-24.08.2018 DATES : WEB SITE HTTPS :// WWW .EMU .EE /EN /ADMISSION S/EXCHANGE -STUDIES /ERASMUS / PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL STUDENT APPLICATIONS FOR OUR ESTILC COURSE SHOULD BE SENT BY E -MAIL TO THE FOLLOWING ADDRESS : APPLICATION DEADLINE 31.05.2018 STAFF JOB TITLE / NAME ADDRESS , TELEPHONE , FAX , E-MAIL CONTACT PERSON ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES FOR ESTILC KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA LIISI VESKE PHONE : +372 731 3174 JOB TITLE FAX : +372 731 3037 PROGRAMME COORDINATOR E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE ESTONIAN UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES KREUTZWALDI 56/1, 51014 TARTU /E STONIA RESPONSIBLE PERSON FOR THE PROGRAMME PHONE : +372 731 3174 FAX : +372 731 3037 LIISI VESKE E-MAIL : LIISI .V ESKE @EMU .EE PART I: GENERAL INFORMATION • DESCRIPTION OF TOWN - SHORT HISTORY AND LOCATION 1 Tartu is the second largest city of Estonia. Tartu is located 185 kilometres to south from the capital Tallinn. Tartu is known also as the centre of Southern Estonia. The Emajõgi River, which connects the two largest lakes (Võrtsjärv and Peipsi) of Estonia, flows for the length of 10 kilometres within the city limits and adds colour to the city. As Tartu has been under control of various rulers throughout its history, there are various names for the city in different languages. -

Estonia's Memory Politics in the Context of European Integration

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2011 Estonia's Memory Politics in the Context of European Integration Marina Suhhoterina West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Suhhoterina, Marina, "Estonia's Memory Politics in the Context of European Integration" (2011). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4799. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4799 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Estonia’s Memory Politics in the Context of European Integration Marina Suhhoterina Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Chair Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2011 Keywords: Estonia; European Integration; the Soviet Union; legacy of communism; Memory Politics Copyright 2011 Marina Suhhoterina ABSTRACT Estonia’s Memory Politics in the Context of European Integration Marina Suhhoterina This study examines the process of European integration of Estonia from the perspective of memory politics. -

Estonian Review E E S T I R I N G V a a D E VOLUME 16 NO 40 OCT 20 - 24, 2006

Estonian Review E E S T I R I N G V A A D E VOLUME 16 NO 40 OCT 20 - 24, 2006 THE STATE VISIT OF HER MAJESTY FOREIGN NEWS QUEEN ELIZABETH II AND HRH EU Leaders Discuss Energy, Innovation at PRINCE PHILIP, THE DUKE OF Informal Meeting in Finland EDINBURGH TO ESTONIA Oct 20 - An informal meeting of European Union leaders in the Finnish town of Lahti focused on questions of energy policy and innovation. EU leaders attached importance to presenting a united front on questions of reliability of energy supplies and competitiveness - issues they also brought up when meeting Russian President Vladimir Putin. Heads of state and government of the bloc's member states found that it is essential to ensure adequate investment in the Russian energy sector but that this requires acceptance of principles of market economy and transparency on Russia's part to secure a reliable investment environment. Both sides admitted that energy dependence is mutual. The head of the Estonian government, Andrus Ansip, said the EU must speak about energy questions in one voice. Meeting with the Russian president was in his Thousands of people gathered in the Town Hall words a first and vital step on this road. Square to greet Queen Elizabeth II According to Ansip, other member countries' support for the necessity of linking the Baltic States' power networks with the EU market was important to Estonia. "Our concerns are also our partners' concerns," he said. Closer ties with the networks of Nordic countries and Central European networks via Poland would increase Estonia's energy-related independence. -

15-L. Films Abra Ensemble Yaron Abulafia

Bios of PQ Projects Participants | Page 1 15-L. FILMS Sala Beckett / Theatre and International Drama Centre (Performance Space Exhibition) 15-L. FILMS is a production company based in Barcelona, created in 2013 by Carlota Coloma and Adrià Lahuerta. They produce documentaries for cinema and other platforms, and for agencies and clients who want to explore the documentary genre in all its possibilities. Their productions have been selected and awarded in many festivals: MiradasDoc, Milano International Documentary Festival, HotDocs and DOCSMX among others. They have been selected to participate in several workshops and pitches such as: IDW Visions du Réel; Cross Video Days; Docs Barcelona. ABRA ENSEMBLE Hall I + Abra Ensemble (Performance Space Exhibition) ABRA Ensemble's works aspire to undermine existing power structures as they express themselves in the voice, language patterns and ways of speech. They seek rather communal, feminist strategies of composition, listening and creative-coexistence. Exposing the emergence of the music itself, ABRA Ensemble bridges the existing limits between contemporary virtuoso vocal art and the performative, transformative encounter with an audience. In the five years since its founding in 2013, the ensemble has performed at a diverse range of venues in Israel and Europe, released a debut album and gained considerable recognition both in the new-music and contemporary performance scene. YARON ABULAFIA Jury Member 2019 / PQ Ambassador Yaron Abulafia has designed over 200 theatre and dance performances, installations, concerts and television shows internationally. He has designed for the Netherlands Dans Theater, the English National Ballet, Rambert Dance Company, Staatsballett Berlin, Danza Contemporanea de Cuba and the Hungarian State Theatre of Cluj in Romania – to mention but a few. -

![Urban Energy Planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3273/urban-energy-planning-in-tartu-pleec-report-d4-2-tartu-gro%C3%9Fe-juliane-groth-niels-boje-fertner-christian-tamm-jaanus-alev-kaspar-1533273.webp)

Urban Energy Planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar

Urban energy planning in Tartu [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu] Große, Juliane; Groth, Niels Boje; Fertner, Christian; Tamm, Jaanus; Alev, Kaspar Publication date: 2015 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Große, J., Groth, N. B., Fertner, C., Tamm, J., & Alev, K. (2015). Urban energy planning in Tartu: [PLEEC Report D4.2 / Tartu]. EU-FP7 project PLEEC. http://pleecproject.eu/results/documents/viewdownload/131-work- package-4/579-d4-2-urban-energy-planning-in-tartu.html Download date: 29. Sep. 2021 Deliverable 4.2 / Tartu Urban energy planning in Tartu 20 January 2015 Juliane Große (UCPH) Niels Boje Groth (UCPH) Christian Fertner (UCPH) Jaanus Tamm (City of Tartu) Kaspar Alev (City of Tartu) Abstract Main aim of report The purpose of Deliverable 4.2 is to give an overview of urban en‐ ergy planning in the 6 PLEEC partner cities. The 6 reports il‐ lustrate how cities deal with dif‐ ferent challenges of the urban energy transformation from a structural perspective including issues of urban governance and spatial planning. The 6 reports will provide input for the follow‐ WP4 location in PLEEC project ing cross‐thematic report (D4.3). Target group The main addressee is the WP4‐team (universities and cities) who will work on the cross‐ thematic report (D4.3). The reports will also support a learning process between the cities. Further, they are relevant for a wider group of PLEEC partners to discuss the relationship between the three pillars (technology, structure, behaviour) in each of the cities. Main findings/conclusions The Estonian planning system allots the main responsibilities for planning activities to the local level, whereas the regional level (county) is rather weak. -

OFFICE ESTONIA Estonia and the European Debt and Economic Crisis

OFFICE ESTONIA Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. ESTONIA THOMAS SCHNEIDER March 2013 Estonia and the European Debt www.kas.de/estland and Economic Crisis AN OVERVIEW With beginning of 2011 Estonia has adopted the Euro and completed its integration into the Eurozone. In fact, this marked the culmination of a drastic re- orientation regarding the Estonian economy: From a former Soviet Union (SU) planned economy to a Western market economy. The process has begun in the early 1990s with Mart Laar's government implementing a number of economic and political reforms in order to pave the way towards economic freedom and prosperity and democratic stability. In the beginning of its journey from the SU to the European Union (EU), Estonia faced Soviet Ruble inflation exceeding 1.000 percentages, soaring unemployment and political uncertainty. In 2011, the Baltic Tiger enjoyed a solid, well-balanced state budget and a debt of only 6.6 percentages of its gross domestic product (GDP). Recent data by the European Central Bank (ECB) indicates that Estonia is together with Luxemburg and Finland one of the few member states in the Euro-Zone that has sufficient financial resources in order to repay its debt. Estonia’s path towards the Eurozone When the SU collapsed in the early 1990s, the Estonian political and economic situation was dire: Inflation of the Soviet Ruble was soaring and exceeding 1.000 percentages, unemployment was on the rise, social inequalities and crime increased swiftly. Furthermore, the transitional government and later Mart Laar's cabinet faced a 30 percentages decline in annual manufacturing output and the complete collapse of the agricultural sector. -

Estonia OECD

Sigma Public Management Profiles No. 12 Estonia OECD https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5kmk183c199q-en SS IGMA Support for Improvement in Governance and Management in Central and Eastern European Countries PUBLIC MANAGEMENT PROFILES OF CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES: ESTONIA ESTONIA (AS OF OCTOBER 1999) Political Background Estonia regained its independence on 20 August 1991. Since then, there have been three elections to the parliament and two elections to the office of the president of the republic. During this period, nine changes of government have also taken place. The president of Estonia is Lennart Meri. He was elected to his second term in office in September 1996. The third elections to the Riigikogu – the parliament of Estonia – took place on 7 March 1999. Seven parties achieved representation in the Riigikogu, with seats allocated as listed in the table below: Party Seats Estonian Centre Party 28 Reform Party 18 Pro Patria Union 18 Mõõdukad Party 17 Estonian Country People’s Party 7 Estonian Coalition Party 7 Estonian United People’s Party 6 The coalition government was formed by the Reform Party, the Pro Patria Union and the Mõõdukad Party, and is headed by Prime Minister Mart Laar. The next ordinary elections of the Riigikogu are scheduled for March 2003. 1. The Constitutional Framework 1.1 Constitutional Bases Estonia is a constitutional democracy with a written constitution. The Constitution of the Republic of Estonia and its implementation Act were adopted by referendum on 28 June 1992 and entered into force the following day. Since its adoption, no amendments have been made to the constitution. -

July 2016 World Orienteering Championships 2017 Tartu

BULLETIN 2 July 2016 World Orienteering Championships 2017 Tartu - Estonia 30.06.-07.07.2017 WELCOME TO ESTONIA! I am glad to welcome you to Estonia to attend the World Orienteering Championships in Tartu. I would encourage you to discover more of the cosiest country and our p rettiest countryside with only 1.3 million inhabitants and 45 thousand squre kilometres of land. Some call Estonia the smartest country as it produces more start-ups per capita than any other country in Europe. Our small country has become the best in e-democracy and e-government, being the first in the world to introduce online political voting. Needless to say, there is a WiFi-net that covers nearly all of the territory. Estonians have an identity card that allows us to access over 1,000 public services online, like healthcare and paying taxes. Being one of the most digitally advanced nations in the world, we decided to start the e-residency project and letting people from around the world become digital residents of Estonia online. Here you can start a new company online fastest, just in under 20 minutes. We love innovation but we value our roots. Estonians have one of the biggest collections of folk songs in the world, with written records of 133,000 folk songs. Our capital Tallinn is the best preserved medieval city in Northern Eu- rope. You might say Estonia is also the greenest country as forests cover about 50% of the territory, or around 2 million hectares. It is one of the most sparsely populated countries in Europe, but there are over 2,000 islands, 1,000 lakes and 7,000 rivers.