Creative Placemaking for Whom, by Whom: Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

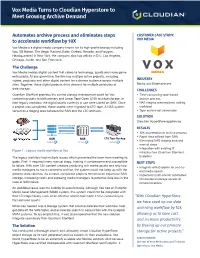

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, a Solid Start and a New Beginning for a New Century

August 1999 In light of recent events in intercollegiate athletics, it seems particularly timely to offer this Internet version of the combined reports of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. Together with an Introduction, the combined reports detail the work and recommendations of a blue-ribbon panel convened in 1989 to recommend reforms in the governance of intercollegiate athletics. Three reports, published in 1991, 1992 and 1993, were bound in a print volume summarizing the recommendations as of September 1993. The reports were titled Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, A Solid Start and A New Beginning for a New Century. Knight Foundation dissolved the Commission in 1996, but not before the National Collegiate Athletic Association drastically overhauled its governance based on a structure “lifted chapter and verse,” according to a New York Times editorial, from the Commission's recommendations. 1 Introduction By Creed C. Black, President; CEO (1988-1998) In 1989, as a decade of highly visible scandals in college sports drew to a close, the trustees of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (then known as Knight Foundation) were concerned that athletics abuses threatened the very integrity of higher education. In October of that year, they created a commission on Intercollegiate Athletics and directed it to propose a reform agenda for college sports. As the trustees debated the wisdom of establishing such a commission and the many reasons advanced for doing so, one of them asked me, “What’s the down side of this?” “Worst case,” I responded, “is that we could spend two years and $2 million and wind up with nothing to show of it.” As it turned out, the time ultimately became more than three years and the cost $3 million. -

Bias Made Tangible Visions of L.A.'S Transformation Captivate Times

Bias made tangible https://www.pressreader.com/usa/los-angeles-times/20140917/282127814684179 Jennifer Eberhardt, a Stanford researcher, wins a MacArthur ‘genius’ grant for showing how we link objects with race By Geoffrey Mohan 17 Sep 2014 Geoffrey Mohan joined the Los Angeles Times in 2001 from Newsday, where he was the Latin America bureau chief in Mexico City. He started off here as a statewide roamer, detoured to cover the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and was part of the team that won the Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the California wildfires in2003. He served as an editor on the metro and foreign desks before returning to reporting on science in 2013 .Now he’s coming full circle, roaming the state in search of stories about farming and food. Can Oregon's tiny houses be part of the solution to homelessness? https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/apr/01/oregon-tiny-houses-solution-homelessness#img-2 Jason Wilson in Portland April 1, 2015 Since 1950, the American family home has become two and a half times larger, even as fewer people on average are living in them. Is it time to downsize? Visions of L.A.'s transformation captivate Times Summit on the future of cities http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-summit-future-cities-20161006-snap-story.html By Bettina Boxall October 8, 2016 Bettina Boxall covers water issues and the environment for the Los Angeles Times. She shared the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting with colleague Julie Cart for a five-part series that explored the causes and effects of escalating wildfire in the West. -

The Criminalization of Private Debt a Pound of Flesh the Criminalization of Private Debt

A Pound of Flesh The Criminalization of Private Debt A Pound of Flesh The Criminalization of Private Debt © 2018 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 4 How the Court System Is Used to Send Debtors to Jail .................................................................... 5 The Role of Civil Court Judges ............................................................................................................. 6 Prosecutors and Debt Collectors as Business Partners ................................................................... 7 A System That Breeds Coercion and Abuse ....................................................................................... 7 Key Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... 7 A Nation of Debtors on the Financial Edge .............................................................................................. 9 The Debt-to-Jail Pipeline ............................................................................................................................12 State and Federal Laws That Allow the Jailing of Debtors .............................................................14 When Judges Reflexively Issue Arrest Warrants for Debtors .......................................................15 How Courts Use the Threat of Jail to Extract Payment ...................................................................16 -

Boston Real Estate's Field of Dreams Your Email Here GO Wednesday, April 3, 2013, by Tom Acitelli

City BOSTON TOP STORIES Search Curbed Boston DEBUTS PRICECHOPPER CONSTRUCTION WATCH Meet 740 Tremont, the South One of Boston's Biggest Dining Sausage Parcel Back on the End's Old New Hope Church Rooms Really Wants Guests Grill! 399 Congress as Apartments BATES BY THE NUMBERS SIGN UP FOR OUR NEWSLETTER Boston Real Estate's Field of Dreams Your email here GO Wednesday, April 3, 2013, by Tom Acitelli Here is the latest installment of Bates By the Numbers, a weekly feature by Boston REAL ESTATE LISTINGS broker David Bates that drills down into the Hub's housing market to uncover those trends you would not otherwise see. This week, he gets an idea from baseball's Opening Day. (Last week, he deep-dove into the region's ultra- luxury market and came up with mind-blowing stats.) 160-164 CANAL STREET 205 PORTLAND STREET CURBED'S GUIDE TO 239 CAUSEWAY BUYING AND RENTING 98 NORTH WASHINGTON Curbed University delivers STREET insider tips and non-boring advice on how to buy or rent a house or apartment. BATES BY THE NUMBERS BULFINCH TRIANGLE Curbed’s Guide to Buying in Boston Big Questions—and Answers!—on Buying FENWAY TRIANGLE Here’s the Lowdown on Mortgages MILLENNIUM PLACE Look Out for Listings Red Flags MILLENNIUM TOWER Closing the Deal NORTHPOINT Curbed’s Guide to Renting in Boston Curbed’s Guide to Neighborhoods in Boston PARCEL 15 COMMENTS PIER 4 Like 4 [Photo by Jonathan Berk] PORTSIDE AT PIER ONE FOLLOW CURBED BOSTON If I was going to field a Boston real estate team this spring, I would probably have Bruce Percelay of the Mount Vernon Company hit in the lead-off SEAPORT DISTRICT position. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ORR PARTNERS ENGAGED BY VOX MEDIA Reston, VA (January 12, 2016) — Vox Media has selected Orr Partners to manage the expansion of their 1201 Connecticut Avenue office in Washington, DC. The modern media company will utilize the additional space to accommodate the rapid growth of its major brands. The improvements include: • Seating for approximately 100 staff • Recording facilities • Conference and teaming areas • Ancillary / teaming space “We are excited we were selected for this exciting and challenging project,” commented Scott Siegel, President of Orr Partners. “We appreciate Vox’s confidence in our team.” The project will commence immediately with assembly of the full project team and completion of the design. “Vox has a great energy about them,” stated Clif White, Senior Project Manager for Orr Partners. “I look forward to working closely with the project team to deliver a project we will all be proud of.” The project will deliver in spring of 2016. ABOUT ORR PARTNERS Orr Partners, an award-winning Project Management firm in Reston, Virginia, is a leading provider of owner's representation services. Specializing in complex project management, Orr Partners provides services for a diverse client base in multiple disciplines including corporate tenant improvements, multi-family, educational, religious, industrial, healthcare, manufacturing, and public sector work. For more detailed information, please email [email protected], visit orrpartners.com or call Scott Siegel at 703-289-2132. For more information on Orr’s property management business, MacGregor Property Management, visit magregorpm.com. For more information on Orr’s safety and QA/QC business, NSBI, visit nsbuilding.com. -

1. Curriculm Vitae

NICK GELPI ASSISTANT PROFESSOR FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY (e) [email protected] (p) 646‐410‐5168 1. CURRICULM VITAE EDUCATION Masters of Science in Advanced Architectural Design, Columbia University, 2003. Bachelor of Architecture, Tulane University, Tulane School of Architecture, 2002. FULL TIME ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Florida International University, Assistant Professor, Architectural Design, August 2012 – present. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, School of Architecture and Planning, Lecturer, Architectural Design, August 2009 ‐ January 2012. The Ohio State University, Austin E. Knowlton School of Architecture, Howard E. LeFevre ’29 Emerging Practitioner Fellowship in Architecture, Visiting Assistant Professor, Architectural Design, September 2008 ‐ June 2009. PART‐TIME ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE Parsons The New School of Design School of Constructed Environments, Instructor, Summer Intensive Studies in Architecture 2, Summer 2011 + Summer 2012. NON ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE GELPI Projects llc, Miami, FL, Founder and Design Principal, 2011 – present. Steven Holl Architects, New York, NY, Lead Project Designer, Project Team Member, 2004 – 2008, 2009. N Architects, New York, NY, Project Manager, 2004. EMPLOYMENT RECORD AT FIU Assistant Professor, 2012 – present. PUBLICATIONS IN DISCIPLINE BOOKS Gelpi, Nick. FROM REPRESENTATION TO REALITY / The Architecture of Full Scale Mockups. New York: Routledge, Expected publication date Winter 2018. (Book Contract signed October 2014, Manuscript submitted to publisher May 2018, Expected publication date: Winter 2018.) ARTICLE, PEER REVIEWED “Pervasively Exotic: Alien Concrete in Miami.” CLOG, MIAMI. Masthead, Canada. (2013) 50‐51. ARTICLES, NOT PEER REVIEWED (NPR) “BALLOONING (HOLLOW THIN 3D)Notes on Practice,” in Hirschman, Sarah, ed., TESTING TO FAILURE: Design and Research in MIT’s Department of Architecture, SA+P Press, Cambridge, 2011, ISBN:978-0-9836654-0-3, pp194‐195. -

The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate

NEW YORK, THE REAL ESTATE Jerry Speyer Michael Bloomberg Stephen Ross Marc Holliday Amanda Burden Craig New- mark Lloyd Blankfein Bruce Ratner Douglas Durst Lee Bollinger Michael Alfano James Dimon David Paterson Mort Zuckerman Edward Egan Christine Quinn Arthur Zecken- dorf Miki Naftali Sheldon Solow Josef Ackermann Daniel Boyle Sheldon Silver Steve Roth Danny Meyer Dolly Lenz Robert De Niro Howard Rubinstein Leonard Litwin Robert LiMandri Howard Lorber Steven Spinola Gary Barnett Bill Rudin Ben Bernanke Dar- cy Stacom Stephen Siegel Pam Liebman Donald Trump Billy Macklowe Shaun Dono- van Tino Hernandez Kent Swig James Cooper Robert Tierney Ian Schrager Lee Sand- er Hall Willkie Dottie Herman Barry Gosin David Jackson Frank Gehry Albert Behler Joseph Moinian Charles Schumer Jonathan Mechanic Larry Silverstein Adrian Benepe Charles Stevenson Jr. Michael Fascitelli Frank Bruni Avi Schick Andre Balazs Marc Jacobs Richard LeFrak Chris Ward Lloyd Goldman Bruce Mosler Robert Ivanhoe Rob Speyer Ed Ott Peter Riguardi Scott Latham Veronica Hackett Robert Futterman Bill Goss Dennis DeQuatro Norman Oder David Childs James Abadie Richard Lipsky Paul del Nunzio Thomas Friedan Jesse Masyr Tom Colicchio Nicolai Ourouso! Marvin Markus Jonathan Miller Andrew Berman Richard Brodsky Lockhart Steele David Levinson Joseph Sitt Joe Chan Melissa Cohn Steve Cuozzo Sam Chang David Yassky Michael Shvo 100The 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate Bloomberg, Trump, Ratner, De Niro, the Guy Behind Craigslist! They’re All Among Our 100 Most Powerful People in New York Real Estate ower. Webster’s Dictionary defines power as booster; No. 15 Edward Egan, the Catholic archbish- Governor David Paterson (No. -

Vox Nears Deal for NYC Office at 85 Broad

Vox nears deal for NYC office at 85 Broad Billiondollar digital media firm eyeing 70K square feet of space at FiDi tower November 12, 2015 03:15PM By Rich Bockmann and Mark Maurer 1 « PREVIOUS NEXT » Vox Media CEO Jim Bankoff and 85 Broad Street in the Financial District UPDATED, Nov. 13, 9:54 a.m.: Vox Media is closing in on a New York office in the Financial District, according to sources. The online publisher is in advanced discussions to sign a lease for more than 70,000 square feet at 85 Broad Street. Vox, which is headquartered in Washington, D.C., and operates websites such as Curbed, SB Nation and Vox.com, is valued at $1 billion following a $200 million investment from NBCUniversal in August. In New York, it currently occupies more than 21,000 square feet at Princeton International’s 104 West 40th Street. By the end of November, it is expected to commit to two full floors at 85 Broad, a 30story, 1.1 millionsquarefoot building that was Goldman Sachs’ headquarters for three decades. Vox would be the latest media company, after Time Inc. and Condé Nast, to move Downtown. CBRE’s Jeff Fischer and JLL’s Steven Rotter are representing Vox, while a JLL team led by Frank Doyle and Jonathan Schifrin are representing the building, which is owned by MetLife and Beacon Capital Partners. The brokers either declined to comment or could not be reached. The lease would bring the building closer to full occupancy. Asking rents in the building are in the $50s and $60s per square foot. -

Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock

TACKLING CLIMATE CHANGE THROUGH LIVESTOCK A GLOBAL ASSESSMENT OF EMISSIONS AND MITIGATION OPPORTUNITIES NGE THROUGH LIVESTOCK A TE CH A CKLING CLIM Ta TACKLING CLIMATE CHANGE THROUGH LIVESTOCK A GLOBAL ASSESSMENT OF EMISSIONS AND mitigation OPPortunitieS FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2013 Recommended citation Gerber, P.J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., Falcucci, A. & Tempio, G. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock – A global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Rome. Photo credits Cover and page 15: @SIE-Masterfile Page 1: @FAO/Giulio Napolitano Page 5: @FAO/Noah Seelam Page 23: @FAO/Giulio Napolitano, Vasily Maximov, Jim Holmes, Florita Botts, Tariq Tinazay Page 45: @iStockphoto.com/Kickers Page 59: @FAO/Ishara Kodikara Page 83: @International Telecommunication Union The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. -

Vox Media Flourishes with Scalable Solutions and Support from Chesapeake Systems

VOX MEDIA FLOURISHES WITH SCALABLE SOLUTIONS AND SUPPORT FROM CHESAPEAKE SYSTEMS Archive, asset management, workflow automation, and storage solutions have paved the path for Vox Media’s future growth, providing new functionality that addresses rising trends and viable revenue streams for the company. CASE STUDY Photos by ©Chris Leonard, courtesy of Gensler WWW.CHESA.COM CASE STUDY VOX MEDIA OVERVIEW Premium digital media company Vox Media has grown exponentially over the past 12 years, currently encompassing eight authoritative editorial networks – SB Nation, The Verge, Polygon, Curbed, Eater, Racked, Vox, and Recode. In addition to its position as a powerhouse new media company, Vox Media’s underlying technology has played a key role in the company’s success. Vox Media’s brands are built on the company’s proprietary modern media stack, Chorus, and ad marketplace, Concert. 1 CHESA CHESA.COM 410.752.7729 CASE STUDY VOX MEDIA ABOUT VOX MEDIA On the content creation side, Vox Media’s emphasis on visual impact has driven tremendous growth. For the past six years, Marcos Bueno, Head of Media Technology based at the company’s New York City headquarters, has spearheaded the infrastructure used by Vox Creative, the company’s branded content division. Like all video producers today, the Vox Media studio team requires a robust, reliable, and secure post-production pipeline for effective asset management and archiving. As content creation continues to explode at Vox Media, Bueno has come to rely on Chesapeake Systems as an engaged partner for providing solutions to the team’s evolving needs. “We started working with Chesapeake about four years ago,” Bueno recalls. -

Housing Element

HOUSING ELEMENT PART I: DATA AND NEEDS ANALYSIS MARCH 2011 | ADOPTED BY PLANNING COMMISSION Cover photo courtesy of Flickr http://www.flickr.com/photos/bookrep/2776433902 Contents Introduction: Data and Needs Analysis 01 I. Population, Employment and Income Trends 03 A. Population and Demographics 04 B. Employment 12 C. Income 15 II. Housing Characteristics 21 A. Existing Housing Stock 22 B. Housing Tenure and Affordability 34 C. Vacancy 37 D. Coastal Zone Housing 39 III. Housing Needs 41 A. Regional Housing Needs Assessment 41 B. Housing Affordability Needs 44 C. Housing Needs of Special Population Groups 48 D. Housing Preservation Needs 57 E. Replacement of Lost Units 58 IV. Meeting Housing Needs 61 A. New Housing Development Potential Under Existing Zoning 62 B. Constraints to Housing Access, Production and Conservation 73 1. Equal Housing Opportunity 73 2. Non-Governmental Constraints 74 3. Governmental Constraints 81 4. Financing 91 C. Quantified Housing Goals 93 D. Realization of Housing Potential 94 1. Projects in the Pipeline 94 2. Housing Potential Under New Zoning Proposals 95 3. Plans for Future Affordable Housing 95 4. Opportunity Sites on Public Lands 96 PART 1: DATA NEEDS & ANALYSIS Tables, Figures, & Maps Table I-1 Population Trends and ABAG Projections, San Francisco, 1990–2030 4 Figure I-1 Population Trends and ABAG Projections, San Francisco, 1940–2030 4 Table I-2 Population Trends and Projections by Age Groups, San Francisco, 1990-2030 5 Figure I-2 Population Trends and Projections by Age Groups, San Francisco, 1990–2030