2003 Conference Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M8-M9 EXHIBITION.Qxd

M8 India Abroad April 25, 2008 the magazine ART Tara Sabharwal’s Tree Path. As a student, she sold her work to London’s Victoria and Albert Museum Bridging gaps: or Roopa Singh, political poet, adjunct professor The artist of international political science at Pace University and theater instructor with South Asian Youth Action (both in New York), Erasing Borders 2008 — which is currently showing in FNew York — is a deeply diverse exhibit. “An extremely talks back affirming taste of how creative our Diaspora is,” she says. “From eerie florescent gas masks on Bharat Natyam dancers, to blood-hued mangoes for breakfast, to sari and sex pistol clad Desi women ‘stenciled’ on wallpaper, to a playful piece on the New York City sewer caps inscribed in Forty Diaspora artists express their South Asian identity in the US with the bold: Made In India. This is us bearing witness to our- traveling exhibition, Erasing Borders, reports Arthur J Pais selves, a South Asian Diaspora, spread and alive.” Vijay Kumar, curator for the fifth edition of the Erasing childhood; images from pop culture including Bollywood Borders traveling exhibition, has been watching the films, advertising and fashion; strong social commentary; changing Indian art scene in New York for several decades. traditional miniature painting transformed and used for “There are many new ‘Indian’ galleries in New York and new purposes; calligraphy and script; startling juxtaposi- other cities now, fueled by the new wealth in India and the tions; work trying to ‘find a home’ within the psyche.” booming art market there,” he says. “These galleries most- By the time India and Pakistan celebrated 50 years of ly show work by artists still living in India; occasionally, Independence, the words Desi and Diaspora had become they do exhibit work by Diaspora artists.” commonplace, he continues. -

Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture 113

Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture 113 Alicja Piechucka Fifteen Minutes of Fame, Fame in Fifteen Minutes: Andy Warhol and the Dawn of Modern-Day Celebrity Culture Life imitates art more than art imitates life. –Oscar Wilde Celebrity is a mask that eats into the face. –John Updike If someone conducted a poll to choose an American personality who best embodies the 1960s, Andy Warhol would be a strong candidate. Pop art, the movement Warhol is typically associated with, flourished in the 60s. It was also during that decade that Warhol’s career peaked. From 1964 till 1968 his studio, known as the Silver Factory, became not just a hothouse of artistic activity, but also the embodiment of the zeitgeist: the “sex, drugs and rock’n’roll” culture of the period with its penchant for experimentation and excess, the revolution in morals and sexuality (Korichi 182–183, 206–208). The seventh decade of the twentieth century was also the time when Warhol opened an important chapter in his painterly career. In the early sixties, he started executing celebrity portraits. In 1962, he completed series such as Marilyn and Red Elvis as well as portraits of Natalie Wood and Warren Beatty, followed, a year later, by Jackie and Ten Lizes. In total, Warhol produced hundreds of paintings depicting stars and famous personalities. This major chapter in his artistic career coincided, in 1969, with the founding of Interview magazine, a monthly devoted to cinema and to the celebration of celebrity, in which Warhol was the driving force. The aim of this essay is to analyze Warhol’s portraits of famous people in terms of how they anticipate the celebrity-obsessed culture in which we now live. -

Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996

Kernos Revue internationale et pluridisciplinaire de religion grecque antique 12 | 1999 Varia Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 DOI: 10.4000/kernos.724 ISSN: 2034-7871 Publisher Centre international d'étude de la religion grecque antique Printed version Date of publication: 1 January 1999 Number of pages: 207-292 ISSN: 0776-3824 Electronic reference Angelos Chaniotis, Joannis Mylonopoulos and Eftychia Stavrianopoulou, « Epigraphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 », Kernos [Online], 12 | 1999, Online since 13 April 2011, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/kernos/724 Kernos Kemos, 12 (1999), p. 207-292. Epigtoaphic Bulletin for Greek Religion 1996 (EBGR 1996) The ninth issue of the BEGR contains only part of the epigraphie harvest of 1996; unforeseen circumstances have prevented me and my collaborators from covering all the publications of 1996, but we hope to close the gaps next year. We have also made several additions to previous issues. In the past years the BEGR had often summarized publications which were not primarily of epigraphie nature, thus tending to expand into an unavoidably incomplete bibliography of Greek religion. From this issue on we return to the original scope of this bulletin, whieh is to provide information on new epigraphie finds, new interpretations of inscriptions, epigraphieal corpora, and studies based p;imarily on the epigraphie material. Only if we focus on these types of books and articles, will we be able to present the newpublications without delays and, hopefully, without too many omissions. -

I – Introduction

QUEERING PERFORMATIVITY: THROUGH THE WORKS OF ANDY WARHOL AND PERFORMANCE ART by Claudia Martins Submitted to Central European University Department of Gender Studies In partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts in Gender Studies CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2008 I never fall apart, because I never fall together. Andy Warhol The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back again CEU eTD Collection CONTENTS ILLUSTRATIONS..........................................................................................................iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................vi CHAPTER 1 - Introduction .............................................................................................7 CHAPTER 2 - Bringing the body into focus...................................................................13 CHAPTER 3 - XXI century: Era of (dis)embodiment......................................................17 Disembodiment in Virtual Spaces ..........................................................18 Embodiment Through Body Modification................................................19 CHAPTER 4 - Subculture: Resisting Ajustment ............................................................22 CHAPTER 5 - Sexually Deviant Bodies........................................................................24 CHAPTER 6 - Performing gender.................................................................................29 -

Sister Corita's Summer of Love

Sister Corita’s Summer of Love Sister Corita’s Summer of Love Sister Corita teaching at Immaculate Heart College, Los Angeles, ca. 1967. Sister Corita Kent is an artists’ artist. In 2008, Corita’s sensibilities were fostered by Corita’s work is finally getting its due in contemporaries Colin McCahon and Ed Ruscha, while travelling through the United States doing and advanced the concerns of the Second the United States, with numerous recent shows, and by the Wellington Media Collective and research, I kept encountering her work on the Vatican Council (1962–5), commonly known but she remains under-recognised outside the Australian artist Marco Fusinato. Similarly, for walls of artists I was visiting and fell in love with as ‘Vatican II’, which moved to modernise the US. Despite our having the English language the City Gallery Wellington show, their Chief it. Happily, one of those artists steered me toward Catholic Church and make it more relevant to in common—and despite its resonance with Curator Robert Leonard has developed his own the Corita Art Center, in Los Angeles, where I contemporary society. Among other things, it Colin McCahon’s—her work is little known in sidebar exhibition, including works by McCahon could learn more. Our show Sister Corita’s Summer advocated changes to traditional liturgy, including New Zealand. So, having already included her in and Ruscha again, New Zealanders Jim Speers, of Love resulted from that visit and offers a journey conducting Mass in the vernacular instead several exhibitions in Europe, when I began my Michael Parekowhai, and Michael Stevenson, through her life and work. -

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

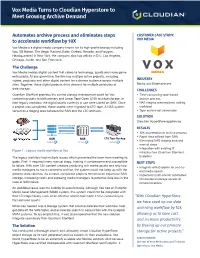

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Andy Warhol Was Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928 and Died in Manhattan in 1987

ANDY WARHOL Andy Warhol was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1928 and died in Manhattan in 1987. He attended free art classes offered at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh at a young age. In 1945, after graduating high school, he enrolled at the Carnegie Institute for Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University), focused his studies on pictorial design, and graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1949. Shortly after, Warhol moved to New York City to pursue a career in commercial art. In the late 1950s, Warhol redirected his attention to painting, and famously debuted “pop art”. In 1964, Warhol opened “The Factory”, which functioned as an art studio, and became a cultural hub for famous socialites and celebrities. Warhol’s work has been presented at major institutions and is featured in innumerous prominent collections worldwide. ANDY WARHOL B. 1928, D. 1987 LIVED AND WORKED IN NEW YORK, NY SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Andy Warhol: Self Portrait (Fright Wigs), Skarstedt Upper East Side, New York (NY) The Age of Ambiguity: Abstract Figuration, Figurative Abstraction, Vito Schnabel Gallery, St Moritz (Switzerland) 2016 Andy Warhol - Idolized, David Benrimon Fine Art, New York (NY) Andy Warhol - Shadows, Yuz Museum Shanghai (Shanghai) Andy Warhol: Sunset, The Menil Collection, Houston, TX Andy Warhol: Contact - M. Woods Beijing (China) Andy Warhol: Portraits, Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento, CA) Andy Warhol: Works from the Hall Collection, Ashmolean Museum (Oxford, England) Warhol: Royal, Moco Museum (Amsterdam, Netherlands) I‘ll be your mirror. Screen Tests von Andy Warhol, Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst (GfZK) (Leipzig, Germany) Andy Warhol: Icons - The Fralin Museum of Art, University of Virginia Art Museums (Charlottesville, VA) Andy Warhol - Little Electric Chairs, Venus Over Manhattan (New York City, NY) Andy Warhol - Shadows, Honor Fraser (Los Angeles, CA) Andy Warhol - Artist Rooms, Firstsite (Colchester, UK) Andy Warhol Portraits, Crocker Art Museum (Sacramento, CA) Andy Warhol. -

Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, a Solid Start and a New Beginning for a New Century

August 1999 In light of recent events in intercollegiate athletics, it seems particularly timely to offer this Internet version of the combined reports of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. Together with an Introduction, the combined reports detail the work and recommendations of a blue-ribbon panel convened in 1989 to recommend reforms in the governance of intercollegiate athletics. Three reports, published in 1991, 1992 and 1993, were bound in a print volume summarizing the recommendations as of September 1993. The reports were titled Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, A Solid Start and A New Beginning for a New Century. Knight Foundation dissolved the Commission in 1996, but not before the National Collegiate Athletic Association drastically overhauled its governance based on a structure “lifted chapter and verse,” according to a New York Times editorial, from the Commission's recommendations. 1 Introduction By Creed C. Black, President; CEO (1988-1998) In 1989, as a decade of highly visible scandals in college sports drew to a close, the trustees of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (then known as Knight Foundation) were concerned that athletics abuses threatened the very integrity of higher education. In October of that year, they created a commission on Intercollegiate Athletics and directed it to propose a reform agenda for college sports. As the trustees debated the wisdom of establishing such a commission and the many reasons advanced for doing so, one of them asked me, “What’s the down side of this?” “Worst case,” I responded, “is that we could spend two years and $2 million and wind up with nothing to show of it.” As it turned out, the time ultimately became more than three years and the cost $3 million. -

The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers

OriginalverCORE öffentlichung in: A. Erskine (ed.), A Companion to the Hellenistic World,Metadata, Oxford: Blackwell citation 2003, and similar papers at core.ac.uk ProvidedS. 431-445 by Propylaeum-DOK CHAPTKR TWENTY-FIVE The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers Anßdos Chaniotis 1 Introduction: the Paradox of Mortal Divinity When King Demetrios Poliorketes returned to Athens from Kerkyra in 291, the Athenians welcomed him with a processional song, the text of which has long been recognized as one of the most interesting sources for Hellenistic ruler cult: How the greatest and dearest of the gods have come to the city! For the hour has brought together Demeter and Demetrios; she comes to celebrate the solemn mysteries of the Kore, while he is here füll of joy, as befits the god, fair and laughing. His appearance is majestic, his friends all around him and he in their midst, as though they were stars and he the sun. Hail son of the most powerful god Poseidon and Aphrodite. (Douris FGrH76 Fl3, cf. Demochares FGrH75 F2, both at Athen. 6.253b-f; trans. as Austin 35) Had only the first lines of this ritual song survived, the modern reader would notice the assimilaüon of the adventus of a mortal king with that of a divinity, the etymo- logical association of his name with that of Demeter, the parentage of mighty gods, and the external features of a divine ruler (joy, beauty, majesty). Very often scholars reach their conclusions about aspects of ancient mentality on the basis of a fragment; and very often - unavoidably - they conceive only a fragment of reality. -

New Perspectives on American Jewish History

Transnational Traditions Transnational TRADITIONS New Perspectives on American Jewish History Edited by Ava F. Kahn and Adam D. Mendelsohn Wayne State University Press Detroit © 2014 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2014936561 ISBN 978-0-8143-3861-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-0-8143-3862-9 (e-book) Permission to excerpt or adapt certain passages from Joan G. Roland, “Negotiating Identity: Being Indian and Jewish in America,” Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies 13 (2013): 23–35 has been granted by Nathan Katz, editor. Excerpts from Joan G. Roland, “Transformation of Indian Identity among Bene Israel in Israel,” in Israel in the Nineties, ed. Fredrick Lazin and Gregory Mahler (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996), 169–93, reprinted with permission of the University Press of Florida. CONN TE TS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 PART I An Anglophone Diaspora 1. The Sacrifices of the Isaacs: The Diffusion of New Models of Religious Leadership in the English-Speaking Jewish World 11 Adam D. Mendelsohn 2. Roaming the Rim: How Rabbis, Convicts, and Fortune Seekers Shaped Pacific Coast Jewry 38 Ava F. Kahn 3. Creating Transnational Connections: Australia and California 64 Suzanne D. Rutland PART II From Europe to America and Back Again 4. Currents and Currency: Jewish Immigrant “Bankers” and the Transnational Business of Mass Migration, 1873–1914 87 Rebecca Kobrin 5. A Taste of Freedom: American Yiddish Publications in Imperial Russia 105 Eric L. Goldstein PART III The Immigrant as Transnational 6. -

Bias Made Tangible Visions of L.A.'S Transformation Captivate Times

Bias made tangible https://www.pressreader.com/usa/los-angeles-times/20140917/282127814684179 Jennifer Eberhardt, a Stanford researcher, wins a MacArthur ‘genius’ grant for showing how we link objects with race By Geoffrey Mohan 17 Sep 2014 Geoffrey Mohan joined the Los Angeles Times in 2001 from Newsday, where he was the Latin America bureau chief in Mexico City. He started off here as a statewide roamer, detoured to cover the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and was part of the team that won the Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the California wildfires in2003. He served as an editor on the metro and foreign desks before returning to reporting on science in 2013 .Now he’s coming full circle, roaming the state in search of stories about farming and food. Can Oregon's tiny houses be part of the solution to homelessness? https://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/apr/01/oregon-tiny-houses-solution-homelessness#img-2 Jason Wilson in Portland April 1, 2015 Since 1950, the American family home has become two and a half times larger, even as fewer people on average are living in them. Is it time to downsize? Visions of L.A.'s transformation captivate Times Summit on the future of cities http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-summit-future-cities-20161006-snap-story.html By Bettina Boxall October 8, 2016 Bettina Boxall covers water issues and the environment for the Los Angeles Times. She shared the 2009 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory reporting with colleague Julie Cart for a five-part series that explored the causes and effects of escalating wildfire in the West. -

The Criminalization of Private Debt a Pound of Flesh the Criminalization of Private Debt

A Pound of Flesh The Criminalization of Private Debt A Pound of Flesh The Criminalization of Private Debt © 2018 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... 4 How the Court System Is Used to Send Debtors to Jail .................................................................... 5 The Role of Civil Court Judges ............................................................................................................. 6 Prosecutors and Debt Collectors as Business Partners ................................................................... 7 A System That Breeds Coercion and Abuse ....................................................................................... 7 Key Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... 7 A Nation of Debtors on the Financial Edge .............................................................................................. 9 The Debt-to-Jail Pipeline ............................................................................................................................12 State and Federal Laws That Allow the Jailing of Debtors .............................................................14 When Judges Reflexively Issue Arrest Warrants for Debtors .......................................................15 How Courts Use the Threat of Jail to Extract Payment ...................................................................16