Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, a Solid Start and a New Beginning for a New Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Men's Basketball Coaching Records

MEN’S BASKETBALL COACHING RECORDS Overall Coaching Records 2 NCAA Division I Coaching Records 4 Coaching Honors 31 Division II Coaching Records 36 Division III Coaching Records 39 ALL-DIVISIONS COACHING RECORDS Some of the won-lost records included in this coaches section Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. have been adjusted because of action by the NCAA Committee 26. Thad Matta (Butler 1990) Butler 2001, Xavier 15 401 125 .762 on Infractions to forfeit or vacate particular regular-season 2002-04, Ohio St. 2005-15* games or vacate particular NCAA tournament games. 27. Torchy Clark (Marquette 1951) UCF 1970-83 14 268 84 .761 28. Vic Bubas (North Carolina St. 1951) Duke 10 213 67 .761 1960-69 COACHES BY WINNING PERCENT- 29. Ron Niekamp (Miami (OH) 1972) Findlay 26 589 185 .761 1986-11 AGE 30. Ray Harper (Ky. Wesleyan 1985) Ky. 15 316 99 .761 Wesleyan 1997-05, Oklahoma City 2006- (This list includes all coaches with a minimum 10 head coaching 08, Western Ky. 2012-15* Seasons at NCAA schools regardless of classification.) 31. Mike Jones (Mississippi Col. 1975) Mississippi 16 330 104 .760 Col. 1989-02, 07-08 32. Lucias Mitchell (Jackson St. 1956) Alabama 15 325 103 .759 Coach (Alma Mater), Schools, Tenure Yrs. WonLost Pct. St. 1964-67, Kentucky St. 1968-75, Norfolk 1. Jim Crutchfield (West Virginia 1978) West 11 300 53 .850 St. 1979-81 Liberty 2005-15* 33. Harry Fisher (Columbia 1905) Fordham 1905, 16 189 60 .759 2. Clair Bee (Waynesburg 1925) Rider 1929-31, 21 412 88 .824 Columbia 1907, Army West Point 1907, LIU Brooklyn 1932-43, 46-51 Columbia 1908-10, St. -

Amicus Brief

Nos. 20-512 & 20-520 In The Supreme Court of the United States ----------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION, Petitioner, v. SHAWNE ALSTON, ET AL., Respondents. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- AMERICAN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE, ET AL., Petitioners, v. SHAWNE ALSTON, ET AL. Respondents. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- On Writs Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Ninth Circuit ----------------------------------------------------------------------- BRIEF OF GEORGIA, ALABAMA, ARKANSAS, MISSISSIPPI, MONTANA, NORTH DAKOTA, SOUTH CAROLINA, AND SOUTH DAKOTA AS AMICI CURIAE SUPPORTING PETITIONERS ----------------------------------------------------------------------- CHRISTOPHER M. CARR Attorney General of Georgia ANDREW A. PINSON Solicitor General Counsel of Record ROSS W. B ERGETHON Deputy Solicitor General DREW F. W ALDBESER Assistant Solicitor General MILES C. SKEDSVOLD ZACK W. L INDSEY Assistant Attorneys General OFFICE OF THE GEORGIA ATTORNEY GENERAL 40 Capitol Square, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30334 (404) 458-3409 [email protected] i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Table of Contents ................................................. i Table of Authorities ............................................. ii Interests of Amici Curiae .................................... 1 Summary of the Argument .................................. 3 Argument ............................................................ -

The NCAA News, Appears the School Has Not Conducted Whose Programs Are Not Subject to Inside This Week’S Issue

Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association May 4, 1994, Volume 3 1, Number 18 Rules committee leaves three-point he alone Meetings of the NCAA Men’s ketball is in the best shape it has and successf’ul seasons in recent “There was substantial discussion the count out for another year. and Women’s Basketball Rules ever been. There is just no need for years, and the men’s committee about the distance of the thrcc- In the women’s rules, the 30-set- Committees April 24-26 in Scotts- major changes.” simply did not see a reason to make point line and the five-second ond shot clock and the absence of dale, Arizona, were marked more George Raveling, chair of the a lot of changes.” count,” Raveling said, “and while a lo-second backcourt count also by action tht= committees did not men’s committee and basketball The most significant “non- some sentiment was cxJ>ressed for were discussed but no changes were take than changes they made. coach at the University of Southern changes” in the men’s rules were changing both, neither was made. Janice Shelton, chair of the California, agrt=ed. “The commit- decisions IO keep the three-point .approvcd.” “The shot clock was discussed women’s committee and athletics tee felt the state of the game was line at its current distance and to The five-second count on the specifically. The women have used director at East Tennessee State healthy,” he said. “We have just not reinstate the five-second closc- idribblcr was eliminated a year ago, University, Iloted, “Women’s bas- completed one of the most exciting ly guarded count on the dribbler. -

The Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics: Why It Needs Fixing

The Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics: Why It Needs Fixing A Collection of Related Commentaries By Dr. Frank G. Splitt The Drake Group http://thedrakegroup.org/ December 2, 2009 Telling the truth about a given condition is absolutely requisite to any possibility of reforming it. – Barbara Tuchman The Knight Foundation's signature work is its Journalism Program that focuses on leading journalism excellence into the digital age—excellence meaning the fair, accurate, contextual pursuit of truth. – The Knight Foundation Website, 2009 INTRODUCTION TO THE COMMENTARIES SUMMARY – The Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics was established in 1989 by the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation. Under the strong leadership of its founding co- chairs, the Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh and Dr. William C. Friday, the Commission set forth to put pressure on the NCAA to clean up its own act before Congress stepped in to do it for them. Subsequent to their tenure the Commission strayed far off the course they set. Can colleges control the NCAA? The answer, plain and simple, is no. Neither can the Foundation’s Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics as it is presently structured—it needs to be fixed first. To this end, The Drake Group has urged the president and CEO of the Knight Foundation to take a hard look at the Commission, arguing that the Commission has not only moved off mission, but has morphed into an unofficial arm of the NCAA as well—it seems time for critical introspection. This collection of commentaries tells how and why this situation developed and what might be done about it. -

A New Beginning

VOLUME 40, NO. 3 ■ FALL 2009 WORLD Technology News and Commentary for Deaf and Hard of Hearing People A New Beginning NETWORKING RECOGNITION In the Nation’s Story begins on page 10 Capital PROGRAM ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED SERVICE ADDRESS ALSO INSIDE: 2009 TDI Awards See page 28 Dr. James Marsters See page 30 Permit No. 163 No. Permit Dulles, VA Dulles, 20910-3822 PAID SilverSpring,Maryland U.S. Postage U.S. 8630FentonStreet•Suite604 Non-Profi t Org. t Non-Profi TDI TDI WORLD 1 TDI’S MISSION “TDI provides leadership in achieving equal access to telecommunications, media, and information technologies for deaf and hard of hearing people.” WORLD Volume 40, Number 3 FEATURE ARTICLES Summer 2009 Editor-in-Chief: Claude Stout Managing Editor: James House Advertising: Chad Metcalf Publication Production: Electronic Ink A New Beginning in the Nation’s Capitol .................................................................................................pg 10 TDI BOARD OF DIRECTORS NORTHEAST REGION 2009 TDI Awards ...........................................................................................................................................pg 28 Phil Jacob (NJ) [email protected] TDI Mourns the Passing of TTY Pioneer, Dr. James Marsters ............................................................pg 30 SOUTHEAST REGION Fred Weiner (MD), Vice President NEWS FLASH! (Senate Introduces Companion Bill to H.R. 3101) ......................................................pg 29 [email protected] MIDWEST REGION Stephanie -

The Follies of Democracy Promotion Leaders, Both Allies and Foes and Allies Leaders, Both Establishment, Policy World Foreign World

A HOOVER INSTITUTION ESSAY ON MIDDLE EAST STRATEGY ChaLLENGES The Follies of Democracy Promotion THE AMERICAN ADVENTURE IN EGYPT SAMUEL TADROS “If you want to put Obama in a bad mood, tell him he has to go to a Situation Room meeting about Egypt.” This striking statement by an administration official appeared in an article accompanying Jeffrey Goldberg’s “The Obama Doctrine” in The Atlantic.1 Analyzing the president’s worldview, David Frum described him as a man disappointed with the world. America’s military leaders and foreign policy establishment, world leaders, both allies and foes—no one escaped the president’s ire at a world that had failed to live up to his expectations. In the flurry of analysis focusing on larger questions, the comment about Egypt received no attention. Such disregard was unfortunate. In a long list of Barack Obama’s disappointments, Egypt ranked high. Order International the and Islamism It was after all in that country’s capital that Obama had given his famed speech in 2009, promising a new beginning with the Muslim world. Less than two years later, the Egyptian people were lavishly praised from the White House’s podium. “Egyptians have inspired us,” declared a jubilant Obama on February 11, 2011. “The people of Egypt have spoken, their voices have been heard, and Egypt will never be the same.” Little did the president realize how ridiculous his statements would soon appear to be. Obama may have grown disappointed with Egypt, but he was hardly the only one. Democratic and Republican policymakers alike, foreign policy wonks and newspaper editorial boards, and even regular Americans found the country’s turn of events astonishing. -

Tripadvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson As President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit

TripAdvisor Appoints Lindsay Nelson as President of the Company's Core Experience Business Unit October 25, 2018 A recognized leader in digital media, new CoreX president will oversee the TripAdvisor brand, lead content development and scale revenue generating consumer products and features that enhance the travel journey NEEDHAM, Mass., Oct. 25, 2018 /PRNewswire/ -- TripAdvisor, the world's largest travel site*, today announced that Lindsay Nelson will join the company as president of TripAdvisor's Core Experience (CoreX) business unit, effective October 30, 2018. In this role, Nelson will oversee the global TripAdvisor platform and brand, helping the nearly half a billion customers that visit TripAdvisor monthly have a better and more inspired travel planning experience. "I'm really excited to have Lindsay join TripAdvisor as the president of Core Experience and welcome her to the TripAdvisor management team," said Stephen Kaufer, CEO and president, TripAdvisor, Inc. "Lindsay is an accomplished executive with an incredible track record of scaling media businesses without sacrificing the integrity of the content important to users, and her skill set will be invaluable as we continue to maintain and grow TripAdvisor's position as a global leader in travel." "When we created the CoreX business unit earlier this year, we were searching for a leader to be the guardian of the traveler's journey across all our offerings – accommodations, air, restaurants and experiences. After a thorough search, we are confident that Lindsay is the right executive with the experience and know-how to enhance the TripAdvisor brand as we evolve to become a more social and personalized offering for our community," added Kaufer. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

America's New Beginning | a Program for Economic Recovery

AMERICA’S NEW BEGINNING: A P R O G R A M FOR ECONOMIC RECOVERY F E B R U A R Y 18, 1981 NOTICE Embargoed-for Wire Transmission Until 4:00 p.m. (E.S.T.) and Embargoed for Release Until 9:00 p.m. (E.S.T.) Wednesday, February 18,1981 The White House Office of the Press Secretory Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis America’s New Beginning : A Program for Economic Recovery C o n t e n t s I. Presidential Message to the Congress II. A White House Report III. President’s Budget Reform Plan IV. President’s Proposals for Tax Reduction Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis I. Presidential M essage to the Congress Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis THE WHITE HOUSE WAS HINGTO N February 18, 1981 TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES: It Is with pleasure that I take the opportunity this evening to make my first major address to the Congress. The address briefly describes the comprehensive package that I am proposing In order to achieve a fu ll and vigorous recovery for our economy. The key elements of that package are four i n n u m b e r : A budget reform plan to cut the rate of growth in Federal spending; A series of proposals to reduce personal income tax rates by 10 percent a year over three years and to create jobs by accelerating depreciation for business investment in plant and equipment; A far-reaching program of regulatory relief; And, in cooperation with the Federal Reserve Board, a new commitment to a monetary policy that w ill restore a stable currency and healthy financial m a r k e t s . -

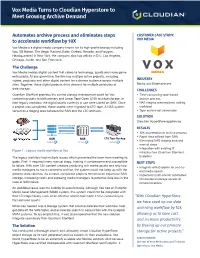

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Illegal Defense: the Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 1-1-2004 Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael McCann University of New Hampshire School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Collective Bargaining Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Sports Management Commons, Sports Studies Commons, Strategic Management Policy Commons, and the Unions Commons Recommended Citation Michael McCann, "Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft," 3 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L. J.113 (2004). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: 3 Va. Sports & Ent. L.J. 113 2003-2004 Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline (http://heinonline.org) Mon Aug 10 13:54:45 2015 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at http://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: https://www.copyright.com/ccc/basicSearch.do? &operation=go&searchType=0 &lastSearch=simple&all=on&titleOrStdNo=1556-9799 Article Illegal Defense: The Irrational Economics of Banning High School Players from the NBA Draft Michael A.