Youth and Hooliganism in Sports Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football"

"Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football" Budim, Antun Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:340000 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-30 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Hungarian Language and Literature Antun Budim Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football Bachelor's Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Jadranka Zlomislić, Assistant Professor Osijek, 2018 J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Hungarian Language and Literature Antun Budim Sport Matters: Hooliganism and Corruption in Football Bachelor's Thesis Scientific area: humanities Scientific field: philology Scientific branch: English studies Supervisor: Dr. Jadranka Zlomislić, Assistant Professor Osijek, 2018 Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskog jezika -

Second International Congress of Art History Students Proceedings !"#$%&&'"

SECOND INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF ART HISTORY STUDENTS PROCEEDINGS !"#$%&&'" !"#$%&'() Klub studenata povijesti umjetnosti Filozofskog fakulteta (Art History Students' Association of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences) (*%+,)%-$ #,-)* Jelena Behaim, Kristina Brodarić, Lucija Bužančić, Ivan Ferenčak, Jelena Mićić, Irena Ravlić, Eva Žile )(.%(/()& Tanja Trška, Maja Zeman (*%+%01 -0* !),,2)(-*%01 Ivana Bodul, Kristina Đurić, Petra Fabijanić, Ana Kokolić, Tatjana Rakuljić, Jasna Subašić, Petra Šlosel, Martin Vajda, Ira Volarević *(&%10 + $-3,"+ Teo Drempetić Čonkić (oprema čonkić#) The Proceedings were published with the financial support from the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb. SECOND INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF ART HISTORY STUDENTS PROCEEDINGS !"#$%&'() Klub studenata povijesti umjetnosti Filozofskog fakulteta (Art History Students' Association of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences) %&#* 978-953-56930-2-4 Zagreb, 2014 ƌ TABLE OF CONTENTS ! PREFACE " IS THERE STILL HOPE FOR THE SOUL OF RAYMOND DIOCRÈS? THE LEGEND OF THE THREE LIVING AND THREE DEAD IN THE TRÈS RICHES HEURES — )*+,- .,/.0-12 #" THE FORGOTTEN MACCHINA D’ALTARE IN THE CHURCH LADY OF THE ANGELS IN VELI LOŠINJ — 3*/+, 45*6),7 $% GETTING UNDER THE SURFACE " NEW INSIGHTS ON BRUEGEL’S THE ASS AT SCHOOL — 8*69/* +*906 &' THE FORMER HIGH ALTAR FROM THE MARIBOR CATHEDRAL — -*706:16* 5*-71; (% EVOCATION OF ANTIQUITY IN LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY ART: THE TOILETTE OF AN ATHENIAN WOMAN BY VLAHO BUKOVAC — *6* 8*3*/9<12 %& A TURKISH PAINTER IN VERSAILLES: JEAN#ÉTIENNE LIOTARD AND HIS PRESUMED PORTRAIT OF MARIE!ADÉLAÏDE OF FRANCE DRESSED IN TURKISH COSTUME — =,)*6* *6.07+,-12 ># IRONY AND IMITATION IN GERMAN ROMANTICISM: MONK BY THE SEA, C.$D. -

The Open Sore of Football: Aggressive Violent Behavior and Hooliganism

PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT. STUDIES AND RESEARCH DOI: 10.1515/pcssr-2016-0015 The Open Sore of Football: Aggressive Violent Behavior and Hooliganism Authors’ contribution: Osman GumusgulA,C,D, Mehmet AcetB,E A) conception and design of the study B) acquisition of data Dumlupinar University, Turkey C) analysis and interpretation of data D) manuscript preparation E) obtaining funding ABSTRACT Aggression and violence have been a customary part of life that mankind has had to live with from the beginning of time; it has been accepted by society even though it expresses endless negativity. Aggression and violence can find a place in sports events and football games because of the social problems of the audience watching the competitions or games, which sometimes fall into the category of hooliganism. Turkey is one of the countries that should consider this problem to be a serious social problem. Even during 2014 and 2015, a relatively short period of time, there were significant hazardous acts committed by hooligans. In February 2014, one supporter was killed after a game between Liverpool and Arsenal in England; in March 2014, a game between Trabzonspor and Fenerbahce was left half-finished because of violent acts in the stadium that caused players in the pitch to believe that they could not leave stadium alive, although they finally left after a few hours; in another incident in March 2014, one supporter was killed after a game between Helsingborg and Djugarden in Sweden; in November 2014, one supporter was killed and 14 supporters were injured before the game between Atletico Madrid and Deportivo in Spain. -

Report of the Consultative Visit in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Strasbourg, 29 May 2012 EPAS (2012) 26 ENLARGED PARTIAL AGREEMENT ON SPORT (EPAS) Report of the Consultative visit in Bosnia and Herzegovina on the European Sports Charter, as well as the implementation of the Recommendation Rec(2001)6 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on the prevention of racism, xenophobia and racial intolerance in sport EPAS (2012) 26 TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Auto-evaluation reports by the authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina Overview of the organisation and state structures Report on European Sport Charter Report on Rec (2001) 6 B. Report of the evaluation team C. Comments from Bosnia and Herzegovina Appendices: Final programme The Law on Sport in Bosnia and Herzegovina EPAS (2012) 26 A. Auto-evaluation reports by the authorities of Bosnia and Herzegovina BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA MINISTRY OF CIVIL AFFAIRS Summary Report Overview of sports organizations and state structures Sarajevo, October 2010 1. INSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURE 1.1. The Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina – The Ministry of Civil Affairs of Bosnia and Herzegovina The BiH Sports Law regulates the sport in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the public interest and objectives of the competence of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Republic of Srpska and the Federation of BiH and the Brčko District of BiH and other levels of the administrative organization. The Sports Department operates within the Ministry and was established on 1 January 2009. The responsibilities of the Sports Department are defined by Article 60 of the BiH Sports Law ("Official Gazette of -

SUBKULTURESUBKULTURE Prispevki Za Kritiko in Analizo Družbenih Gibanj XII

SUBKULTURESUBKULTURE prispevki za kritiko in analizo družbenih gibanj XII. SUBKULTURNI AZIL MARIBOR, 2013 Frontier 073 Zbornik SUBKULTURE: prispevki za kritiko in analizo družbenih gibanj, XII. št. Tematska izdaja: Socializacija in socialne formacije © Subkulturni azil, zavod za umetniško produkcijo in založništvo, 2013 Vse pravice pridržane. Nobenega dela te knjige ni dovoljeno ponatisniti, reproducirati ali posredovati s kakršnimikoli sredstvi, elektronskimi, mehanskimi, s fotokopiranjem, zvokovnim snemanjem ali kako drugače, brez poprejšnjega pisnega dovoljenja založbe Subkulturni azil. Uredil: dr. Andrej Naterer Odgovorna urednica: Tatjana-Tanja Cvitko Lektorirala: Nina Klaučič Recenzenta: doc. dr. Marina Tavčar Krajnc, doc. dr. Smiljana Gartner Oblikovanje ovitka: Zlatko Kuret Oblikovanje in prelom: PDesign, Peter Dobaj s.p. Izdal: Subkulturni azil, zavod za umetniško produkcijo in založništvo, Maribor http://www.ljudmila.org/subkulturni-azil Za založbo: Branko Hedl Tisk: Ale d.o.o., Postojna Naklada: 500 izvodov Izid knjige so podprli: Javna agencija za knjigo Republike Slovenije Mestna občina Maribor Dravske elektrarne Maribor Notesniki.si CIP - Kataložni zapis o publikaciji Univerzitetna knjižnica Maribor 316.723 SOCIALIZACIJA in socialne formacije / [uredil Andrej Naterer]. - Maribor : Subkulturni azil, zavod za umetniško produkcijo in založništvo, 2013. - (Knjižna zbirka Frontier ; 073) (Subkulture : prispevki za kritiko in analizo družbenih gibanj. Tematska izdaja ; št. 12) ISBN 978-961-6620-40-6 1. Naterer, Andrej COBISS.SI-ID -

Ljudska Prava U Srbiji 2012: Populizam, Urušavanje

HELSINŠKI ODBOR ZA LJUDSKA PRAVA U SRBIJI LJUDSKA PRAVA U SRBIJI 2012 POPULIZAM:GODIŠNJI IZVEŠTAJ URUŠAVANJE : SRBIJA DEMOKRATSKIH 2011 VREDNOSTI HELSINŠKI ODBOR ZA LJUDSKA PRAVA U SRBIJI OPSTRUKCIJA EVROPSKOG PUTA HELSINŠKI ODBOR ZA LJUDSKA PRAVA U SRBIJI LJUDSKA PRAVA U SRBIJI 2012 POPULIZAM: URUŠAVANJE DEMOKRATSKIH VREDNOSTI BEOGRAD, 2013 LJUDSKA PRAVA U SRBIJI: 2012 POPULIZAM: URUŠAVANJE DEMOKRATSKIH VREDNOSTI izdavač HELSINŠKI ODBOR ZA LJUDSKA PRAVA U SRBIJI za izdavača Sonja Biserko oblikovanje i slog Ivan Hrašovec Za ilustraciju na naslovnoj strani korišćen crtež Alvara Cabrere štampa Grathia drucht ISBN 978-86-7208-189-3 COBISS.SR-ID 199036940 Ova edicija objavljenja je zahvaljujući finansijskoj pomoći Ambasade Kraljevine Holandije. Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji snosi isključivu odgovornost za sadržaj edicije, za koji se ni pod kojim okolnostima ne može smatrati da odražava stavove Ministarstva inostranih poslova Holandije. CIP – Katalogizacija u publikaciji, Narodna biblioteka Srbije, Beograd 341.231.14(497.11)”2012”, 316.4(497.11)”2012”, 323(497.11)”2012” POPULIZAM : urušavanje demokratskih vrednosti : ljudska prava u Srbiji 2012 / [priredio] Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji. – Beograd : Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji, 2013 (Novi Pazar : Grathia Drucht). – 632 str. ; 23 cm Tiraž 300. – Napomene i bibliografske reference uz tekst. 1. Helsinški odbor za ljudska prava u Srbiji (Beograd) a) Ljudska prava – Međunarodna zaštita – Srbija – 2012 b) Srbija – Društvene prilike – 2012 c) Srbija – Političke -

The Region I Love2.Qxp

мир développement durable civil society intercultural dialogue “The Region Love” This publication is first and foremost for all of those people who live and work in the Region, and who are interested in the Balkans, whether they be youth leaders, or representatives of public authorities or institutions. It is for those people who are interested in hearing and listening to the voice of YouthYouth andand InterculturalIntercultural young people from the Region. As such, this booklet is not an educational learninglearning inin thethe BalkansBalkans manual, it will not provide answers to the challenges it presents. It does not represent any institutions’ official stance, nor that of the Council of Europe. It Voices of young people from the Balkans will not offer any conclusions other than those the reader draws for her/ himself. If the reader wants to share these conclusions with the authors of this booklet, we should be most grateful! This booklet aims to be a tool to contribute to a better understanding within the Region, of the Region, for all youth leaders, youth workers who would like to further develop activities in the Balkans. It is one tool among many for all those people who think of the Balkans as “a Region they love”, a sentiment shared by all of the authors, and, we hope, by all who read it. governancía participación гражданское общество démocratie COUNCIL CONSEIL OF EUROPE DE L'EUROPE "The Region I Love" Youth and intercultural learning in the Balkans Voices of young people from the Balkans Directorate of Youth and Sport Council of Europe The opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not neces- sarily reflect the official position of the Council of Europe. -

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

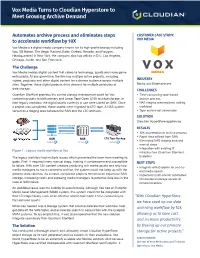

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Violent Fan Groups At... Acta Kinesiologica 11 (2017) Issue 1: 37-43

Baić, V. et al.: Socio-demographic characteristics of violent fan groups at... Acta Kinesiologica 11 (2017) Issue 1: 37-43 SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF VIOLENT FAN GROUPS AT FOOTBALL MATCHES Valentina Baić, Zvonimir Ivanović and Stevan Popović Academy of Criminalistics and Police Studies, Belgrade, Serbia Ministry of interior, Novi Sad, Serbia Original scientific paper Abstract The main objective of the research was to study the most important socio-demographic characteristics of violent fan groups at football matches, as well as criminal activities of their members. The authors in the paper have used data from the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Republic of Serbia, especially originating from Novi Sad Police Department, and from the Section of monitoring violence and misbehavior at sports events, which included a total of 139 members, 18 fan groups, aged 16-40 years. The research results show that in the overall structure of registered members of fan groups, the largest share of adults as well as young adults, who are recruited from families with unfavorable socio-economic status. In terms of other socio- demographic characteristics, the survey results show that members of the fan groups in the highest percentage have finished high school, and that they were unemployed, unmarried and gravitate from the city and partially from suburban areas. In view of their delinquent activities, predominantly author have found crimes against property and crimes and offenses, which is characterized by a particular method of execution that is dominated by violence and the use of various explosive devices. Key words: socio-demographic characteristics, violent fan groups, football hooliganism. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: the FURTHEST

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE FURTHEST WATCH OF THE REICH: NATIONAL SOCIALISM, ETHNIC GERMANS, AND THE OCCUPATION OF THE SERBIAN BANAT, 1941-1944 Mirna Zakic, Ph.D., 2011 Directed by: Professor Jeffrey Herf, Department of History This dissertation examines the Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans) of the Serbian Banat (northeastern Serbia) during World War II, with a focus on their collaboration with the invading Germans from the Third Reich, and their participation in the occupation of their home region. It focuses on the occupation period (April 1941-October 1944) so as to illuminate three major themes: the mutual perceptions held by ethnic and Reich Germans and how these shaped policy; the motivation behind ethnic German collaboration; and the events which drew ethnic Germans ever deeper into complicity with the Third Reich. The Banat ethnic Germans profited from a fortuitous meeting of diplomatic, military, ideological and economic reasons, which prompted the Third Reich to occupy their home region in April 1941. They played a leading role in the administration and policing of the Serbian Banat until October 1944, when the Red Army invaded the Banat. The ethnic Germans collaborated with the Nazi regime in many ways: they accepted its worldview as their own, supplied it with food, administrative services and eventually soldiers. They acted as enforcers and executors of its policies, which benefited them as perceived racial and ideological kin to Reich Germans. These policies did so at the expense of the multiethnic Banat‟s other residents, especially Jews and Serbs. In this, the Third Reich replicated general policy guidelines already implemented inside Germany and elsewhere in German-occupied Europe. -

Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, a Solid Start and a New Beginning for a New Century

August 1999 In light of recent events in intercollegiate athletics, it seems particularly timely to offer this Internet version of the combined reports of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. Together with an Introduction, the combined reports detail the work and recommendations of a blue-ribbon panel convened in 1989 to recommend reforms in the governance of intercollegiate athletics. Three reports, published in 1991, 1992 and 1993, were bound in a print volume summarizing the recommendations as of September 1993. The reports were titled Keeping Faith with the Student-Athlete, A Solid Start and A New Beginning for a New Century. Knight Foundation dissolved the Commission in 1996, but not before the National Collegiate Athletic Association drastically overhauled its governance based on a structure “lifted chapter and verse,” according to a New York Times editorial, from the Commission's recommendations. 1 Introduction By Creed C. Black, President; CEO (1988-1998) In 1989, as a decade of highly visible scandals in college sports drew to a close, the trustees of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation (then known as Knight Foundation) were concerned that athletics abuses threatened the very integrity of higher education. In October of that year, they created a commission on Intercollegiate Athletics and directed it to propose a reform agenda for college sports. As the trustees debated the wisdom of establishing such a commission and the many reasons advanced for doing so, one of them asked me, “What’s the down side of this?” “Worst case,” I responded, “is that we could spend two years and $2 million and wind up with nothing to show of it.” As it turned out, the time ultimately became more than three years and the cost $3 million. -

Thesis Understandingfootball Hooliganism Amón Spaaij Understanding Football Hooliganism

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Understanding football hooliganism : a comparison of six Western European football clubs Spaaij, R.F.J. Publication date 2007 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Spaaij, R. F. J. (2007). Understanding football hooliganism : a comparison of six Western European football clubs. Vossiuspers. http://nl.aup.nl/books/9789056294458-understanding- football-hooliganism.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 AUP/Spaaij 11-10-2006 12:54 Pagina 1 R UvA Thesis amón Spaaij Hooliganism Understanding Football Understanding Football Hooliganism Faculty of A Comparison of Social and Behavioural Sciences Six Western European Football Clubs Ramón Spaaij Ramón Spaaij is Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Amsterdam and a Research Fellow at the Amsterdam School for Social Science Research.