Truth in Los Angeles: Addressing Racial Injustice Through Recognition, Responsibility, and Repair

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Paradigm for Fairness: the First National Conference on Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Bias in the Courts

1.-.- 3 -4185 00322265-I 9 J A New Paradigm for Fairness: The First National Conference on Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Bias in the Courts , P A New Paradigm for Fairness: The First National Conference on Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Bias in the Courts H. Clifton Grandy, J.D Edited by Dawn Spinozza I Chuck Campbell National Center for State Courts State Justice Institute t Q 1995 National Center for State Courts ISBN 0-89656- 160-7 National Center Publication Number 'R- 180 These proceedings were prepared and reproduced with finds fiom the State Justice Insti- tute, Grant Number SJI-93- 12A-C-B- 198-P94-( l -3), for the First NationaZ Conference on Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Bias in the Courts. The points of view expressed are those of the presenters and author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Center for State Courts or the State Justice Institute. Planning Committee Honorable Veronica Simmons McBeth Chair, Planning Committee Los Angeles Municipal Court, California Honorable Benjamin Aranda 111 Dr. Yolande P. Marlow South Bay Municipal Court Project Director, Task Force on Minority California Concerns, New Jersey Marilyn Callaway Honorable Jon J. Mayeda Director, Juvenile Court Services Los Angeles Municipal Court, California San Diego, California Honorable Carl J. Character Joseph A. Myers, Esq. Court of Common Pleas, Cleveland, Ohio Executive Director National Indian Justice Center Honorable Charles R Cloud Rose M. Ochi, Esq. Norfolk General District Court, Virginia Associate Director Office of National Drug Control Policy Honorable Lewis L. Douglass Honorable Charles 2.Smith King’s County Supreme Court, New York Justice, Supreme Court of Washington Dolly M. -

Ictj Briefing

ictj briefing Virginie Ladisch Anna Myriam Roccatello The Color of Justice April 2021 Transitional Justice and the Legacy of Slavery and Racism in the United States The murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in the spring of 2020 at the hands of police have set off a wave of national and international protests demanding that the United States (US) confront its unaddressed legacy of slavery and racial discrimination, manifest in persistent social and economic inequality.1 Compared with previous protest movements in the US, this time, it seems more attention is being paid to the historical roots of the grievances being voiced. Only a few years ago, following the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, protests broke out calling for an array of reforms, such as body cameras and greater accountability for individual police officers. However, across the country, the continued violence against Black people by police highlights that this is not a problem of individuals. It is rather a pervasive and systemic problem that began before the nation’s founding and has been a constant through line in US history from the early colonial period to the present. This history includes the CONTENTS genocide of Native Americans, the enslavement of African Americans, and the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Putting an end to this continuing legacy requires an equally systemic response. A Time for Global Inspiration 2 Acknowledgment and Truth To understand what conditions led to the murder of George Floyd, and so many others Seeking 3 before him and since, it is important to analyze the past and put current grievances in Steps Toward Repair 8 historical perspective. -

Kerner Commission Writing Exercise in July 1967, President Lyndon

Kerner Commission Writing Exercise In July 1967, President Lyndon Johnson formed a National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. The Commission was tasked with understanding why riots were breaking out in different cities across America. The Commission would also provide recommendations on how to address these issues. Their report was finished in 1968 and became informally known as the Kerner Report, named after the Commission Chair, Otto Kerner, Jr., the Governor of Illinois at the time. The Kerner Report stated that the nation was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.” The Kerner report called out “white society” for isolating and neglecting African Americans. It recommended legislation to promote racial integration, create jobs, and provide affordable housing. President Johnson, however, rejected the recommendations. Just one month after the Kerner Report was released, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated (on April 4, 1968). Rioting broke out again in more than 100 cities after the Civil Rights leader’s death. Many people argue that some of the pivotal recommendations made in this report still remain unaddressed today. The following is the Summary Introduction from the 1968 Kerner Report. The summer of 1967 again brought racial disorders to American cities, and with them shock, fear and bewilderment to the nation. The worst came during a two-week period in July, first in Newark and then in Detroit. Each set off a chain reaction in neighboring communities. On July 28, 1967, the President of the United States established this Commission and directed us to answer three basic questions: What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again? To respond to these questions, we have undertaken a broad range of studies and investigations. -

Fundamentos De La Ley 14784

Fundamentos de la Ley 14784 Abelardo Castillo nació en Buenos Aires, en 1.935, y enseguida su familia se trasladó a la localidad de San Pedro, en la provincia de Buenos Aires. Será por eso que desde siempre eligió identificarse como “sampedrino” y es en esa ciudad donde reside en la actualidad. Castillo es uno de los escritores nacionales más importantes, abordando a lo largo de su carrera todos los géneros: poesía, ensayo, cuento, novela y este año publicó sus memorias en forma de diarios. Comenzó a escribir a los 12 años, se formó bajo la influencia de Jean-Paul Sartre y de Albert Camus. Su obra literaria responde a intereses variados y a su propia vida. Desde muy chico, leía con voracidad y alcanzó un reconocimiento considerable cuando aún no había cumplido los 30 años. Junto a otros prestigiosos escritores fundó la revista de literatura El Grillo de Papel, de la que llegaron a aparecer seis números, ya que el gobierno de Arturo Frondizi prohibió la publicación por su adscripción al pensamiento de izquierda y, singularmente, a la lectura del marxismo desarrollada por Jean-Paul Sartre. En 1961 fundó y dirigió, conjuntamente con Liliana Heker, El Escarabajo de Oro. Esta revista -editada hasta el año 1.974- apuntó a una fuerte proyección latinoamericana y fue considerada una de las más representativas de la generación del 60. Formaron parte de su Consejo de Colaboradores: Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Augusto Roa Bastos, Juan Goytisolo, Félix Grande, Ernesto Sábato, Roberto Fernández Retamar, Beatriz Guido, Dalmiro Sáenz, entre otros. Allí publicaron por primera vez sus textos Liliana Heker, Ricardo Piglia, Humberto Constantini, Miguel Briante, Jorge Asís, Alejandra Pizarnik y Haroldo Conti. -

THE PRESS in CROWN HEIGHTS by Carol B. Conaway

FRAMING IDENTITY : THE PRESS IN CROWN HEIGHTS by Carol B. Conaway The Joan Shorenstein Center PRESS ■ POLI TICS Research Paper R-16 November 1996 ■ PUBLIC POLICY ■ Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government FRAMING IDENTITY: THE PRESS IN CROWN HEIGHTS Prologue 1 On the evening of August 19, 1991, the Grand Bystanders quickly formed a crowd around the Rebbe of the Chabad Lubavitch was returning car with the three Lubavitcher men, and several from his weekly visit to the cemetery. Each among them attempted to pull the car off of the week Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, leader of the Cato children and extricate them. Lifsh tried to worldwide community of Lubavitch Hasidic help, but he was attacked by the crowd, consist- Jews, visited the graves of his wife and his ing predominately of the Caribbean- and Afri- father-in-law, the former Grand Rebbe. The car can-Americans who lived on the street. One of he was in headed for the international headquar- the Mercury’s riders tried to call 911 on a ters of the Lubavitchers on Eastern Parkway in portable phone, but he said that the crowd Crown Heights, a neighborhood in the heart of attacked him before he could complete the call. Brooklyn, New York. As usual, the car carrying He was rescued by an unidentified bystander. the Rebbe was preceded by an unmarked car At 8:22 PM two police officers from the 71st from the 71st Precinct of the New York City Precinct were dispatched to the scene of the Police Department. The third and final car in accident. -

Do Guns Preclude Credibility?: Considering the Black Panthers As a Legitimate Civil Rights Organisation

Do Guns Preclude Credibility 7 Do Guns Preclude Credibility?: Considering the Black Panthers as a legitimate Civil Rights organisation Rebecca Abbott Second Year Undergraduate, Monash University Discontent over social, political and racial issues swelled in the United States during the mid- sixties. Even victories for the Civil Rights movement could not stem the dissatisfaction, as evidenced by the Watts riots that broke out in Los Angeles during August 1965, only two weeks after the Voting Rights Act was signed.1 Rioting had become more frequent, thus suggesting that issues existed which the non-violent Civil Rights groups could not fix. In 1966, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders reported that forty-three race riots had occurred across the country, nearly tripling the fifteen previously reported for 1964.2 The loss of faith in mainstream civil rights groups was reflected in a 1970 poll of black communities conducted by ABC-TV in which the Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP) was the only black organisation that ‘respondents thought would increase its effectiveness in the future.’3 This was in contrast to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which the majority thought would lose influence.4 Equality at law had been achieved, but that meant little in city ghettoes where the issues of poverty and racism continued to fester.5 It was from within this frustrated atmosphere that in October 1966, 1 See Robert Charles Smith, We Have No Leaders: African Americans in the Post-Civil Rights Era, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1996), 17. -

OD 1413 DFM.Pmd

CAMARA DE DIPUTADOS DE LA NACION O.D. Nº 1.413 1 SESIONES DE PRORROGA 2008 ORDEN DEL DIA Nº 1413 COMISION DE CULTURA Impreso el día 9 de diciembre de 2008 Término del artículo 113: 18 de diciembre de 2008 SUMARIO: Revista “PROA en las Letras y en las INFORME Artes”, de ALLONI/PROA Editores. Declaración de interés de la Honorable Cámara. Genem. (5.835- Honorable Cámara: D.-2008.) La Comisión de Cultura ha considerado el pro- yecto de declaración de la señora diputada Genem, Dictamen de comisión por el que se declara de interés de la Honorable Cá- mara la revista “PROA en las Letras y en las Artes” Honorable Cámara: de ALLONI/PROA Editores. Las señoras y señores diputados, al iniciar el estudio de esta iniciativa, han La Comisión de Cultura ha considerado el pro- tenido en cuenta que por su vasta trayectoria la re- yecto de declaración de la señora diputada Genem, vista “PROA en las Letras y en las Artes” es consi- por el que se declara de interés de la Honorable Cá- derada decana de los medios literarios de América. mara la revista “PROA en las Letras y en las Ar- Su fundación data de 1922 por iniciativa de Jorge tes”, de ALLONI/PROA Editores; y, por las razones Luis Borges, Macedonio Fernández y Ricardo expuestas en el informe que se acompaña y las que Güiraldes; y, desde 1988, recorre su tercera etapa dará el miembro informante, aconseja la aprobación con una frecuencia bimestral, una tirada de 15.000 del siguiente ejemplares y manteniendo el formato de libro, que le conserva sus características literarias y estéticas. -

Sabato/Borges: Sobre El Cielo Y El Infierno

SABATO/BORGES: SOBRE EL CIELO Y EL INFIERNO POR LELIA M. MADRID University of Western Ontario 4Elaborar otra versi6n sobre el cielo y el infierno? Borges -y Adolfo Bioy Casares-- responden con una antologia, el Libro del cielo y el infierno'. El prologo es de 1959. En 1966, Ernesto Sabato proponia su propia "historia" del cielo y del infierno2. "Sobre la existencia del infierno" es una pieza personal; asi, en efecto, lo declara su autor: (L)a teorfia ... (s)e me ha ocurrido como consecuencia de algunas experiencias personales y, seguramente, bajo la presi6n de fuertes obsesiones inconscientes (217). Mas adelante, aiiade otro comentario de un tenor parecido: No mencionar6 aquf mis experiencias personales que, por serlo, son para mi de enorme e impresionante importancia, pero que para los otros carecen de valor probatorio; debo decir, sin embargo, que son estas experiencias personales, asi como el sonambulismo que me aquej6 de nifio, los que me han empujado hacia el estudio de la parapsicologfa (217). 1 Se hace referencia a la edici6n de Jorge L. Borges y Adolfo Bioy Casares, Libro del cielo y del infierno (Buenos Aires: Sur, 1975). 2 "Sobre la existencia del infierno", fue primeramente publicado en la revista Janus, 6 (Buenos Aires,julio-set. 1966): 91-94 y reimpresa posteriormente en diversos volimenes de ensayos: La robotizacidn del hombre y otros ensayos (Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de Am6rica Latina, 1981): 25-31; tambi6n enPdginas de Ernesto Sdbato (Buenos Aires: Celtia, 1983): 217-222; asimismo, v6ase la p. 305 de la novela Abadd6n el exterminador (Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1978). -

ERNESTO SÁBATO (1911-2011) Pablo Ruiz Tufts University Ernesto

REVISTA DE CRÍTICA LITERARIA LATINOAMERICANA Año XXXVII, No 73. Lima-Boston, 1er semestre de 2011, pp. 467-470 ERNESTO SÁBATO (1911-2011) Pablo Ruiz Tufts University Ernesto Sábato, escritor argentino, ha muerto en su casa de San- tos Lugares, en la provincia de Buenos Aires, el 30 de abril de este año. Autor de tres novelas y varios libros de ensayos, recibió los máximos honores de las letras en lengua española, incluido el Pre- mio Cervantes, y múltiples reconocimientos internacionales por su actividad literaria y política. Había nacido casi cien años antes, el 24 de junio de 1911, en el pequeño pueblo de Rojas, a más de doscientos kilómetros de la ciu- dad de Buenos Aires. Sus padres eran inmigrantes italianos llegados de Calabria a fines del siglo XIX. Fue el décimo de once hijos varo- nes y fue bautizado Ernesto en homenaje al noveno, muerto poco antes de que él naciera. Producto de la educación pública argentina, fue a la escuela primaria en Rojas y al secundario en la ciudad de La Plata, donde fue alumno de Pedro Henríquez Ureña, el gran intelec- tual dominicano, y de Ezequiel Martínez Estrada. En 1929 ingresó a la Facultad de Ciencias Físico-Matemáticas de la Universidad de La Plata, aunque su gran vocación temprana fue la política. En 1930 dictó un curso informal sobre el marxismo, una de cuyas alumnas, Matilde Kusminsky-Richter, sería su futura esposa. En 1933 aban- donó los estudios para dedicarse por completo a la militancia. Fue miembro activo del Partido Comunista y hasta llevó una breve vida clandestina en la localidad de Avellaneda, pero pronto el desencanto con el estalinismo lo llevó a abandonar el comunismo y a retomar sus estudios de física. -

Transitional Justice and the Legacy of Child Sexual Abuse in the Catholic Church

CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE AND THE LEGACY OF CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Elizabeth B. Ludwin King* I. INTRODUCTION In 1998, John Geoghan, a Massachusetts priest, was defrocked— stripped of any rights to perform as an ordained priest—for molesting children.1 Four years later, the Archbishop of Boston, Bernard Law, arguably one of the most influential people in the state, resigned from his position upon revelations that he knew of Geoghan’s actions and yet chose to send him to other parishes where he would still be in an environment with minors.2 In other parishes around and outside the United States, similar scenarios were, and had been, occurring for years: priests using their positions in order to engage in sexual acts with minors.3 When survivors began to speak up, they and their families were often offered “hush money” in order to prevent a scandal.4 Although the sexual abuse crisis came to the forefront in 2002 due to the investigative journalist team at the Boston Globe, reports of the sexual abuse of children by members of the clergy had been * Adjunct Professor, University of Denver Sturm School of Law. Many thanks to Kate Devlin for her research assistance. 1 See CNN, Priest in Sex Abuse Scandal Killed in Prison, CNN.COM (Aug. 23, 2003), http://www.cnn.com/2003/US/08/23/geoghan/. 2 See Rev. Raymond C. O’Brien, Clergy, Sex and the American Way, 31 PEPP. L. REV. 363, 373, 374 (2004). Law died on December 20, 2017 in Rome. -

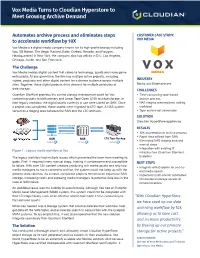

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand

Vox Media Turns to Cloudian Hyperstore to Meet Growing Archive Demand Automates archive process and eliminates steps CUSTOMER CASE STUDY: to accelerate workflow by 10X VOX MEDIA Vox Media is a digital media company known for its high-profile brands including Vox, SB Nation, The Verge, Racked, Eater, Curbed, Recode, and Polygon. Headquartered in New York, the company also has offices in D.C, Los Angeles, Chicago, Austin, and San Francisco. The Challenge Vox Media creates digital content that caters to technology, sports and video game enthusiasts. At any given time, the firm has multiple active projects, including videos, podcasts and other digital content for a diverse audience across multiple INDUSTRY sites. Together, these digital projects drive demand for multiple petabytes of Media and Entertainment data storage. CHALLENGES Quantum StorNext provides the central storage management point for Vox, • Time-consuming tape-based connecting users to both primary and Linear Tape Open (LTO) archival storage. In archive process their legacy workflow, the digital assets currently in use were stored on SAN. Once • NAS staging area required, adding a project was completed, those assets were migrated to LTO tape. A NAS system workload served as a staging area between the SAN and the LTO archives. • Tape archive not searchable SOLUTION Cloudian HyperStore appliances PROJECT COMPLETE RESULTS PROJECT RETRIEVAL • 10X acceleration of archive process • Rapid data offload from SAN SAN NAS LTO Tape Backup • Eliminated NAS staging area and manual steps • Integration with existing IT Figure 1 : Legacy media workflow at Vox infrastructure (Quantum StorNext, The legacy workflow had multiple issues which prevented the team from meeting its Evolphin) goals. -

UD 010 515 Vogt, Carol Busch Why Watts?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 041 997 24 UD 010 515 AUTHOR Vogt, Carol Busch TITLE Why Watts? An American Dilemma Today: Teacher's Manual; Student's Manual, INSTITUTION Amherst Coll., Mass. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-5-1071 PUB DATE [67] CONTRACT OEC-5-10-158 NOTE 46p.; Public Domain Edition EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$2.40 DESCRIPTORS *Activism, Civil Disobedience, Community Problems, *Demonstrations (Civil), Family Characteristics, Ghettos, Instructional Materials, *Negro Attitudes, Police Action, Poverty Programs, Prevention, Student Attitudes, Teaching Guides, Unemployment, *Violence IDENTIFIERS California, Los Angeles, *Watts Community ABSTRPCT Designed to invite the senior and junior high school student tO investigate the immediate and underlying causes of riots and what can be done to prevent them, the student manual of this Unit begins with a description of the Watts riots of 1965, The student is encouraged to draw his own conclusions, and to determine the feasibility of a variety of proposed solutions to this problem after consideration of the evidence drawn from a variety of sources, including novels. Ultimately, the student confronts the dilemtna that the riots pose for American values and institutions, and is asked to articulate his personal role in meeting this challenge. The suggestions in the accompanying teacher manual are considered not to restrict the teacher, but the goals and interests of each teacher and each class are held to determine the exact use of the materials. (RJ) EXPERIMENTAL MATERIAL SUBJECT TO REVISION PUBLIC DOMAIN EDITION TEACHER'S MANUAL WAX WATTS? AN AMERICAN DILEMMA TODAY Carol Busch Vogt North Tonawanda Senior High School North Tonawanda, New York U,S.