UD 010 515 Vogt, Carol Busch Why Watts?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PRESS in CROWN HEIGHTS by Carol B. Conaway

FRAMING IDENTITY : THE PRESS IN CROWN HEIGHTS by Carol B. Conaway The Joan Shorenstein Center PRESS ■ POLI TICS Research Paper R-16 November 1996 ■ PUBLIC POLICY ■ Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government FRAMING IDENTITY: THE PRESS IN CROWN HEIGHTS Prologue 1 On the evening of August 19, 1991, the Grand Bystanders quickly formed a crowd around the Rebbe of the Chabad Lubavitch was returning car with the three Lubavitcher men, and several from his weekly visit to the cemetery. Each among them attempted to pull the car off of the week Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, leader of the Cato children and extricate them. Lifsh tried to worldwide community of Lubavitch Hasidic help, but he was attacked by the crowd, consist- Jews, visited the graves of his wife and his ing predominately of the Caribbean- and Afri- father-in-law, the former Grand Rebbe. The car can-Americans who lived on the street. One of he was in headed for the international headquar- the Mercury’s riders tried to call 911 on a ters of the Lubavitchers on Eastern Parkway in portable phone, but he said that the crowd Crown Heights, a neighborhood in the heart of attacked him before he could complete the call. Brooklyn, New York. As usual, the car carrying He was rescued by an unidentified bystander. the Rebbe was preceded by an unmarked car At 8:22 PM two police officers from the 71st from the 71st Precinct of the New York City Precinct were dispatched to the scene of the Police Department. The third and final car in accident. -

Do Guns Preclude Credibility?: Considering the Black Panthers As a Legitimate Civil Rights Organisation

Do Guns Preclude Credibility 7 Do Guns Preclude Credibility?: Considering the Black Panthers as a legitimate Civil Rights organisation Rebecca Abbott Second Year Undergraduate, Monash University Discontent over social, political and racial issues swelled in the United States during the mid- sixties. Even victories for the Civil Rights movement could not stem the dissatisfaction, as evidenced by the Watts riots that broke out in Los Angeles during August 1965, only two weeks after the Voting Rights Act was signed.1 Rioting had become more frequent, thus suggesting that issues existed which the non-violent Civil Rights groups could not fix. In 1966, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders reported that forty-three race riots had occurred across the country, nearly tripling the fifteen previously reported for 1964.2 The loss of faith in mainstream civil rights groups was reflected in a 1970 poll of black communities conducted by ABC-TV in which the Black Panther Party for Self Defense (BPP) was the only black organisation that ‘respondents thought would increase its effectiveness in the future.’3 This was in contrast to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which the majority thought would lose influence.4 Equality at law had been achieved, but that meant little in city ghettoes where the issues of poverty and racism continued to fester.5 It was from within this frustrated atmosphere that in October 1966, 1 See Robert Charles Smith, We Have No Leaders: African Americans in the Post-Civil Rights Era, (New York: State University of New York Press, 1996), 17. -

"The Who Sings My Generation" (Album)

“The Who Sings My Generation”—The Who (1966) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Cary O’Dell Original album Original label The Who Founded in England in 1964, Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Keith Moon are, collectively, better known as The Who. As a group on the pop-rock landscape, it’s been said that The Who occupy a rebel ground somewhere between the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, while, at the same time, proving to be innovative, iconoclastic and progressive all on their own. We can thank them for various now- standard rock affectations: the heightened level of decadence in rock (smashed guitars and exploding drum kits, among other now almost clichéd antics); making greater use of synthesizers in popular music; taking American R&B into a decidedly punk direction; and even formulating the idea of the once oxymoronic sounding “rock opera.” Almost all these elements are evident on The Who’s debut album, 1966’s “The Who Sings My Generation.” Though the band—back when they were known as The High Numbers—had a minor English hit in 1964 with the singles “I’m the Face”/”Zoot Suit,” it wouldn’t be until ’66 and the release of “My Generation” that the world got a true what’s what from The Who. “Generation,” steam- powered by its title tune and timeless lyric of “I hope I die before I get old,” “Generation” is a song cycle worthy of its inclusive name. Twelve tracks make up the album: “I Don’t Mind,” “The Good’s Gone,” “La-La-La Lies,” “Much Too Much,” “My Generation,” “The Kids Are Alright,” “Please, Please, Please,” “It’s Not True,” “The Ox,” “A Legal Matter” and “Instant Party.” Allmusic.com summarizes the album appropriately: An explosive debut, and the hardest mod pop recorded by anyone. -

Time Bruce's Chords

4th Of July, Asbury Park (Sandy) C F C F C Guitar 1: ------|--8-8<5------|---------------|-------------|---------------| -5----|--------8<6--|-5-/-8—6-------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------7-----|-5-----------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|---7-5-5-----|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|---------7-5vvvv-------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|-------------8-| Guitar 2: All ---5--|-8-----------|-18<15---------|-------------|-15-12-12-10-8-| ------|-------------|-------13-12---|-------------|-15-13-13-10-8-| ------|-------------|-------------13<15-----------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| F C F C Guitar 1: |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |-5vvv\3-|--------------3-|-3/5-8-10/8------| Time Guitar 2: |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |-7\5----|-17\15<13-15-17-|---------|-------| |-----7--|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| Sandy C F C Sandy the fireworks are hailin' over Little Eden tonight Am Gsus G Forcin' a light -

I I I I of The

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. :1 I I REPORT I' ON THE I PROCEEDINGS I I I I OF THE ,I , COMMITTEE OF STATE ASSOCIATIONS I OF CHIEFS OF POLICE I I I EXECUTIVE TRAINING SESSION I I INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CHIEFS OF POLICE "1' II ,.~ CONDUCTED AT ,I 'Q. FARGO. NORTH DAKOTA I JULY 23, 24, AND 25, 1974 I I I I: REPORT ONTRE I PROCEEDINGS OF THE , I COMMITTEE OF STATE ASSOCIATIONS I OF CHIEFS OF POLICE I I EXECUTIVE TRAINING SESSION I I INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF CHIEFS OF POLICE I I CONDUCTED AT I FARGO, NORTH DAKOTA I JULY 23. 24, AND 25, 1974· I I I I ----~----------------_______.,r, _______ I 'I I I I' This Police Executive Training Session was made possible, through Grant Number 74 TA-99-0011. from the Law Enforcement Assistance I Administration. I The authors of this report are the membership of the IACP Committee I of State Associations of Chiefs of Police, and any recommendations. conclusions or opinions expressed herein are those of the authors. and not necessarily those of the Law Enforcement Assistance Admin.is tration. I I I I I I I I I I I I -------------------------. I I BACKGROUND The International Association of Chiefs of Police Committee of State Assoc I iations of Chiefs of Police attained full standing committee status in 1973. Committee membership consists of the current President of each state I association of chiefs of police. I The purpose and goals of the Committee, as outlined in its official Bylaws, are as follows: I "This Committee shall serve as a coordinating body between the several and separate State Associations of Chiefs of I. -

Historical Timeline of the Palms-Mar-Vista-Del

HISTORICAL TIMELINE OF THE Events Significant to Local Development PALMS-MAR-VISTA-DEL REY 1875 Arrival of the Los Angeles & 1920 Independence Railroad into region Formerly known as Barnes 1886 City, Del Rey becomes the Palms (The Palms) is the winter home for Al Barnes’ 1940 first community to be Wild Animal Circus Zoo (zoo Housing subdivisions established in Rancho La moves from Venice, CA) constructed at an 1930 Ballona accelerated rate 1915 Barnes City is officially accommodated Palms is 1927 declared part of the defense-industry annexed to th Special Collections, UCLA Young Research Library Mar Vista is the 70 City of Los Angeles workers during and the City of annexation to Los after World War II Los Angeles Angeles Public domain 1904 1925 Over 500 acres in Ocean Park Heights 1919. California Historical Society Collection, Ocean Park renamed Mar Vista University of Southern California Heights are subdivided and offered for sale 1700 1800 1850 1900 1910 1920 1930 1940 1932 1926 LA hosts Olympic Los Angeles City Hall Games. Later, 1781 athletes’ cottages are constructed 1941 El Pueblo de Los Angeles placed on the beach Pearl Harbor founded as a summer resort. bombed, US enters World War II 1850 California Statehood 1934 1945 US Congress passes the End of World Overland Monthly, August-September 1931 National Housing Act, creating War II Drawing by William Rich Hutton, 1847. USC Digital Library the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Olympic.org Public Domain 1929 Stock Market Crash Events Significant to the Development of the City of Los Angeles 1939 HOLC "redlining" map of central Los Angeles, courtesy of LaDale Winling and urbanoasis.org. -

"The Culture of the 1970S Reflected Through Bruce Springsteen's Music"

"The Culture of the 1970s Reflected Through Bruce Springsteen's Music" Senior Honors Thesis Presented To The Honors College Written By Melody S. Jackson Spring, 1983 Advised By Dr. Anthony Edmonds .;,- () -- "The Culture of the 1970s Reflected Through Bruce Springsteen's Music" I have seen the future of rock and roll and it is Bruce Springsteen. Jon Landau the advent of Bruce Springsteen, who made rock and roll a matter of life and death again, seemed nothing short of a miracle to me . Bruce Springsteen is the last of rock's great innocents. Dave Marsh Whether these respected critics see Springsteen as the future of great rock or the end of it, they do regard him with respect for his ability to convey the basic feeling of rock. And they are not alone in this opinion. From the start of his career, Springsteen has received a great deal of critical acclaim. This acclaim, in part because of his performing ability, seems quite fitting since his shows usually last for two and a half hours and often continue for four or even five hours. Relentlessly, he gives of himself to the thousands of fans -- his cult following -- who have come to see their own Rock Messiah. Upon analysis of the lyrics of Springsteen's songs, lyrics which he has written, one sees that he has a unique talent f()r reflecting the situation of the lower-middle class which he grew up in. In fact, in all of the albums he has released up to this time, he has written about the culture of the lower-middle class. -

The History of Black Firefighters in Los Angeles

THE HISTORY OF BLACK FIREFIGHTERS IN LOS ANGELES Year: Event: 1781 City of Los Angeles is founded. 1850 Los Angeles is incorporated as a city. 1857 U.S. Supreme court rules in Dred Scott vs. Sandford. A black man has no rights that a white man is bound to respect because blacks are not citizens. 1886 Los Angeles Fire Department is organized as a paid Department. 1888 Sam Haskins, born a slave in 1840 from Virginia is listed in the census as an employed Fireman for the city of Los Angeles and assigned to Engine Company #4. 1892 Sam Haskins is appointed as a Call Man and assigned to Engine 2, making him the first black man hired by the Los Angeles Fire Department (LAFD). 1895 Sam Haskins is fatally injured on November 19, while responding down First Street to a fire call. When the steamer he was riding on, hit a bump in the road, Haskins lost his balance and fell between the steamer’s boiler and the wheel. It took firemen and citizens ten minutes to remove the wheel. He was carried back to Engine 2’s quarters where he died that night. 1896 U.S. Supreme Court rules in Plessy vs. Ferguson that “Separate But Equal” is the law of the land. 1897 George Bright is hired as the second black fireman in the LAFD. 1900 William Glenn is hired as the third black fireman in the LAFD. 1902 George Bright obtains the endorsement of the Second Baptist Church and is promoted to Lieutenant. This makes him the first black officer in the Department. -

Runaway American Dream, Hope and Disillusion in the Early Work

Runaway American Dream HOPE AND DISILLUSION IN THE EARLY WORK OF BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Two young Mexican immigrants who risk their lives trying to cross the border; thousands of factory workers losing their jobs when the Ohio steel industry collapsed; a Vietnam veteran who returns to his hometown, only to discover that he has none anymore; and young lovers learning the hard way that romance is a luxury they cannot afford. All of these people have two things in common. First, they are all disappointed that, for them, the American dream has failed. Rather, it has become a bitter nightmare from which there is no waking up. Secondly, their stories have all been documented by the same artist – a poet of the poor as it were – from New Jersey. Over the span of his 43-year career, Bruce Springsteen has captured the very essence of what it means to dream, fight and fail in America. That journey, from dreaming of success to accepting one’s sour destiny, will be the main subject of this paper. While the majority of themes have remained present in Springsteen’s work up until today, the way in which they have been treated has varied dramatically in the course of those more than forty years. It is this evolution that I will demonstrate in the following chapters. But before looking at something as extensive as a life-long career, one should first try to create some order in the large bulk of material. Many critics have tried to categorize Springsteen’s work in numerous ‘phases’. Some of them have reasonable arguments, but most of them made the mistake of creating strict chronological boundaries between relatively short periods of time1, unfortunately failing to see the numerous connections between chronologically remote works2 and the continuity that Springsteen himself has pointed out repeatedly. -

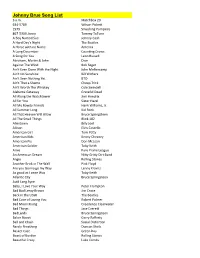

Johnny Brue Song List.Xlsx

Johnny Brue Song List 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 634-5789 Wilson Picke 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 867-5309 Jenny Tommy TuTone A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash A Hard Day's Night The Beatles A Horse with no Name America A Long December Counng Crows A Song for You Leon Russell Abraham, Marn & John Dion Against The Wind Bob Seger Ain't Even Done With the Night John Mellencamp Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't Seen Nothing Yet BTO Ain't That a Shame Cheap Trick Ain't Worth The Whiskey Cole Swindell Alabama Getaway Grateful Dead All Along the Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All for You Sister Hazel All My Rowdy Friends Hank Williams, Jr. All Summer Long Kid Rock All That Heaven Will Allow Bruce Springsteen All The Small Things Blink 182 Allentown Billy Joel Allison Elvis Costello American Girl Tom Pey American Kids Kenny Chesney American Pie Don McLean American Soldier Toby Keith Amie Pure Prarie League An American Dream Niy Griy Dirt Band Angie Rolling Stones Another Brick in The Wall Pink Floyd Are you Gonna go my Way Lenny Kravitz As good as I once Was Toby Keith Atlanc City Bruce Springsteen Auld Lang Syne Baby, I Love Your Way Peter Frampton Bad Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce Back in the USSR The Beatles Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Bad Things Jace Evere BadLands Bruce Springsteen Baker Street Gerry Rafferty Ball and Chain Social Distoron Barely Breathing Duncan Sheik Basket Case Green Day Beast of Burden Rolling Stones Beauful Crazy Luke Combs Johnny Brue Song List Beds are Burning Midnight Oil Beer for my Horses Toby -

FREE SPEECH MOVEMENT TIMELINE Berkeley, California 1964-1965

FREE SPEECH MOVEMENT TIMELINE Berkeley, California 1964-1965 September 14: Dean of Students Katherine Towle sends a letter banning tables from the Bancroft strip 30: SNCC and CORE students are suspended for tabling; 500 people sit in at Sproul Hall October 1-2: Jack Weinberg (CORE) is arrested; students surround the police car; Mario Savio speaks; more than 7,000 rally until an agreement at 7:30pm the next day 3-5: Students organize to create the Free Speech Movement November 7: The administration opposes campus political advocacy; will discipline offenders 9: Students table on Sproul Plaza during negotiations of the committee on political activity 20: Regents meet; probation for Savio and Goldberg; “illegal advocacy” will still be punished 20: Following the meeting, 3,000 students rally to demand full free speech on campus 23: Rally with intra-FSM debate as well as a statement by Vice-Chancellor Seary; Sproul sit-in 24: Academic Senate meeting defeats a motion to limit regulation of political activity 28: Mario Savio and others receive letters stating they may be expelled December 2-4: Savio speaks at Sproul Hall: “You’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears”; Sproul hall is occupied by 800 students; police intervene and over 800 people are arrested 3: General strike led by the Teaching Assistants; picketing on Sproul Plaza 5: Department chairmen create a proposal meeting some of FSM demands; Kerr agrees 7: 16,000 assemble in the Greek Theatre to hear the agreement; amnesty for offenders 8: Academic Senate vote: the University may regulate only time, place, and manner of political activity, with no restrictions on content of speech Jan 2: Chancellor Strong is replaced by Martin Meyerson as Acting Chancellor 3: Meyerson address: Sproul Hall steps and Sproul Plaza are open for tables and discussion BLACK PANTHER PARTY Relevant dates for California activities February 1965: Malcolm X is assassinated August 1965: Watts riots in Los Angeles; Martin Luther King, Jr. -

Race and Race Relations in Los Angeles During the 1990S : the L.A. Times' News Coverage on the Rodney King Incident And

RACE AND RACE RELATIONS IN LOS ANGELES DURING THE 1990s. THE L.A. TIMES’ NEWS COVERAGE ON THE RODNEY KING INCIDENT AND THE ‘L.A. RIOTS’ I N A U G U R A L D I S S E R T A T I O N zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie in der FAKULTÄT FÜR GESCHICHTSWISSENSCHAFT der RUHR UNIVERSITÄT BOCHUM vorgelegt von Kathrin Muschalik Referent: Prof. Dr. Michael Wala Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Josef Raab Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 08.06.2016 Veröffentlicht mit Genehmigung der Fakultät für Geschichtswissenschaft der Ruhr Universität Bochum Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 A History of Cultural, Social and Economic Urban Transformation – Black Los Angeles from 1945 until 1991 .................................................................................................. 14 2.1 Setting the Scene ....................................................................................................... 14 2.2 African American Job and Housing Situation in Postwar Los Angeles ................... 15 2.3 Criss-Crossing Los Angeles – Building Streets for Whites? .................................... 18 2.4 Paving the Way to Watts – Unemployment, Poverty, and Police Brutality ............. 19 2.5 The Aftermath of the Watts ‘Riots’ – Cause Studies and Problem-Solving Approaches ...................................................................................................................... 25 2.6 Of Panthers, Crips, and