I I I I of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"The Who Sings My Generation" (Album)

“The Who Sings My Generation”—The Who (1966) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Cary O’Dell Original album Original label The Who Founded in England in 1964, Roger Daltrey, Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Keith Moon are, collectively, better known as The Who. As a group on the pop-rock landscape, it’s been said that The Who occupy a rebel ground somewhere between the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, while, at the same time, proving to be innovative, iconoclastic and progressive all on their own. We can thank them for various now- standard rock affectations: the heightened level of decadence in rock (smashed guitars and exploding drum kits, among other now almost clichéd antics); making greater use of synthesizers in popular music; taking American R&B into a decidedly punk direction; and even formulating the idea of the once oxymoronic sounding “rock opera.” Almost all these elements are evident on The Who’s debut album, 1966’s “The Who Sings My Generation.” Though the band—back when they were known as The High Numbers—had a minor English hit in 1964 with the singles “I’m the Face”/”Zoot Suit,” it wouldn’t be until ’66 and the release of “My Generation” that the world got a true what’s what from The Who. “Generation,” steam- powered by its title tune and timeless lyric of “I hope I die before I get old,” “Generation” is a song cycle worthy of its inclusive name. Twelve tracks make up the album: “I Don’t Mind,” “The Good’s Gone,” “La-La-La Lies,” “Much Too Much,” “My Generation,” “The Kids Are Alright,” “Please, Please, Please,” “It’s Not True,” “The Ox,” “A Legal Matter” and “Instant Party.” Allmusic.com summarizes the album appropriately: An explosive debut, and the hardest mod pop recorded by anyone. -

Time Bruce's Chords

4th Of July, Asbury Park (Sandy) C F C F C Guitar 1: ------|--8-8<5------|---------------|-------------|---------------| -5----|--------8<6--|-5-/-8—6-------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------7-----|-5-----------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|---7-5-5-----|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|---------7-5vvvv-------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|-------------8-| Guitar 2: All ---5--|-8-----------|-18<15---------|-------------|-15-12-12-10-8-| ------|-------------|-------13-12---|-------------|-15-13-13-10-8-| ------|-------------|-------------13<15-----------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| ------|-------------|---------------|-------------|---------------| F C F C Guitar 1: |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |-5vvv\3-|--------------3-|-3/5-8-10/8------| Time Guitar 2: |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |-7\5----|-17\15<13-15-17-|---------|-------| |-----7--|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| |--------|----------------|---------|-------| Sandy C F C Sandy the fireworks are hailin' over Little Eden tonight Am Gsus G Forcin' a light -

UD 010 515 Vogt, Carol Busch Why Watts?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 041 997 24 UD 010 515 AUTHOR Vogt, Carol Busch TITLE Why Watts? An American Dilemma Today: Teacher's Manual; Student's Manual, INSTITUTION Amherst Coll., Mass. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-5-1071 PUB DATE [67] CONTRACT OEC-5-10-158 NOTE 46p.; Public Domain Edition EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-$2.40 DESCRIPTORS *Activism, Civil Disobedience, Community Problems, *Demonstrations (Civil), Family Characteristics, Ghettos, Instructional Materials, *Negro Attitudes, Police Action, Poverty Programs, Prevention, Student Attitudes, Teaching Guides, Unemployment, *Violence IDENTIFIERS California, Los Angeles, *Watts Community ABSTRPCT Designed to invite the senior and junior high school student tO investigate the immediate and underlying causes of riots and what can be done to prevent them, the student manual of this Unit begins with a description of the Watts riots of 1965, The student is encouraged to draw his own conclusions, and to determine the feasibility of a variety of proposed solutions to this problem after consideration of the evidence drawn from a variety of sources, including novels. Ultimately, the student confronts the dilemtna that the riots pose for American values and institutions, and is asked to articulate his personal role in meeting this challenge. The suggestions in the accompanying teacher manual are considered not to restrict the teacher, but the goals and interests of each teacher and each class are held to determine the exact use of the materials. (RJ) EXPERIMENTAL MATERIAL SUBJECT TO REVISION PUBLIC DOMAIN EDITION TEACHER'S MANUAL WAX WATTS? AN AMERICAN DILEMMA TODAY Carol Busch Vogt North Tonawanda Senior High School North Tonawanda, New York U,S. -

"The Culture of the 1970S Reflected Through Bruce Springsteen's Music"

"The Culture of the 1970s Reflected Through Bruce Springsteen's Music" Senior Honors Thesis Presented To The Honors College Written By Melody S. Jackson Spring, 1983 Advised By Dr. Anthony Edmonds .;,- () -- "The Culture of the 1970s Reflected Through Bruce Springsteen's Music" I have seen the future of rock and roll and it is Bruce Springsteen. Jon Landau the advent of Bruce Springsteen, who made rock and roll a matter of life and death again, seemed nothing short of a miracle to me . Bruce Springsteen is the last of rock's great innocents. Dave Marsh Whether these respected critics see Springsteen as the future of great rock or the end of it, they do regard him with respect for his ability to convey the basic feeling of rock. And they are not alone in this opinion. From the start of his career, Springsteen has received a great deal of critical acclaim. This acclaim, in part because of his performing ability, seems quite fitting since his shows usually last for two and a half hours and often continue for four or even five hours. Relentlessly, he gives of himself to the thousands of fans -- his cult following -- who have come to see their own Rock Messiah. Upon analysis of the lyrics of Springsteen's songs, lyrics which he has written, one sees that he has a unique talent f()r reflecting the situation of the lower-middle class which he grew up in. In fact, in all of the albums he has released up to this time, he has written about the culture of the lower-middle class. -

Runaway American Dream, Hope and Disillusion in the Early Work

Runaway American Dream HOPE AND DISILLUSION IN THE EARLY WORK OF BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN Two young Mexican immigrants who risk their lives trying to cross the border; thousands of factory workers losing their jobs when the Ohio steel industry collapsed; a Vietnam veteran who returns to his hometown, only to discover that he has none anymore; and young lovers learning the hard way that romance is a luxury they cannot afford. All of these people have two things in common. First, they are all disappointed that, for them, the American dream has failed. Rather, it has become a bitter nightmare from which there is no waking up. Secondly, their stories have all been documented by the same artist – a poet of the poor as it were – from New Jersey. Over the span of his 43-year career, Bruce Springsteen has captured the very essence of what it means to dream, fight and fail in America. That journey, from dreaming of success to accepting one’s sour destiny, will be the main subject of this paper. While the majority of themes have remained present in Springsteen’s work up until today, the way in which they have been treated has varied dramatically in the course of those more than forty years. It is this evolution that I will demonstrate in the following chapters. But before looking at something as extensive as a life-long career, one should first try to create some order in the large bulk of material. Many critics have tried to categorize Springsteen’s work in numerous ‘phases’. Some of them have reasonable arguments, but most of them made the mistake of creating strict chronological boundaries between relatively short periods of time1, unfortunately failing to see the numerous connections between chronologically remote works2 and the continuity that Springsteen himself has pointed out repeatedly. -

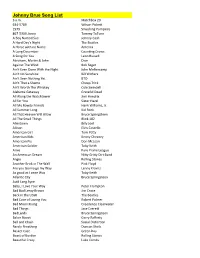

Johnny Brue Song List.Xlsx

Johnny Brue Song List 3 a.m. Matchbox 20 634-5789 Wilson Picke 1979 Smashing Pumpkins 867-5309 Jenny Tommy TuTone A Boy Named Sue Johnny Cash A Hard Day's Night The Beatles A Horse with no Name America A Long December Counng Crows A Song for You Leon Russell Abraham, Marn & John Dion Against The Wind Bob Seger Ain't Even Done With the Night John Mellencamp Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Ain't Seen Nothing Yet BTO Ain't That a Shame Cheap Trick Ain't Worth The Whiskey Cole Swindell Alabama Getaway Grateful Dead All Along the Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All for You Sister Hazel All My Rowdy Friends Hank Williams, Jr. All Summer Long Kid Rock All That Heaven Will Allow Bruce Springsteen All The Small Things Blink 182 Allentown Billy Joel Allison Elvis Costello American Girl Tom Pey American Kids Kenny Chesney American Pie Don McLean American Soldier Toby Keith Amie Pure Prarie League An American Dream Niy Griy Dirt Band Angie Rolling Stones Another Brick in The Wall Pink Floyd Are you Gonna go my Way Lenny Kravitz As good as I once Was Toby Keith Atlanc City Bruce Springsteen Auld Lang Syne Baby, I Love Your Way Peter Frampton Bad Bad Leroy Brown Jim Croce Back in the USSR The Beatles Bad Case of Loving You Robert Palmer Bad Moon Rising Creedence Clearwater Bad Things Jace Evere BadLands Bruce Springsteen Baker Street Gerry Rafferty Ball and Chain Social Distoron Barely Breathing Duncan Sheik Basket Case Green Day Beast of Burden Rolling Stones Beauful Crazy Luke Combs Johnny Brue Song List Beds are Burning Midnight Oil Beer for my Horses Toby -

1) Jungleland

60) Murder Incorporated So the comfort that you keep's a gold-plated, snub-nosed .32 Not quite sure why this doesn’t get more plays. It is a real belter, pumps you up, would be a great show opener. Would have been right at home on Darkness. Has you rocking from go to woe. Bruce leaves nobody behind on this and you’re taken on a six minute power ride, and there is no time for stopping. This was initially recorded back in 1982 with the Born In The USA sessions, but did not see an official release until the release of greatest hits in 1995. From the get go it sounds like classic Springsteen. The thud of Max’s drums, followed with the intro of the guitars. The organs feature prominently too. And for the next six minutes, you feel compelled to tap your foot to the beat and fill with anger, because let’s face it, this song doesn’t exactly put a smile on your face. That’s not to say songs need to have a happy vibe about them to enjoy them. The sax solo feels like it’s just been shoved in for the sake of it. But somehow Bruce managed to make it work. Nils’ wows us with a blistering solo before the bridge and we are treated to one final verse and raspy Bruce belts out a “I could tell you were just frustrated livin with Murder Incoporated.” Bruce struts his stuff and nearly sets his guitar on fire, Stevie throws a punch back (much like the Saint duel at Hammersmith), but Bruce shows why he’s Boss. -

Bruce Springsteen Släpper 'London Calling: Live in Hyde Park'

2010-04-21 16:14 CEST Bruce Springsteen släpper 'London Calling: Live in Hyde Park' Den 23 juni släpper Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band's 'London Calling: Live In Hyde Park' – en inspelning från Hard Rock Calling Festival den 28 juni, 2009 i London. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -------------- COLUMBIA RECORDS TO RELEASE BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN & THE E STREET BAND'S 'LONDON CALLING: LIVE IN HYDE PARK' CONCERT FILM ON JUNE 23 ELEASE MARKS FIRST SPRINGSTEEN OUTDOOR CONCERT FILM AND FIRST FROM A FESTIVAL SETTING On June 23, Columbia Records will release Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band's 'London Calling: Live In Hyde Park' concert film on one Blu-Ray disc and as a two DVD set. Captured in London at the Hard Rock Calling Festival on June 28, 2009 in HD, the 163-minute film documents 26 tracks of live Springsteen that begin in daylight and progress through a gorgeous sunset into night. 'London Calling: Live In Hyde Park' conveys both the experience of being on- stage and the vast crowd experience of the festival environment. Viewers are able to see Springsteen spontaneously directing the E Street Band and shaping the show as it evolves. The set list spans from 'Born To Run' era to 'Working On a Dream' and includes rare covers such as The Clash's "London Calling," Jimmy Cliff's "Trapped," The Young Rascals' "Good Lovin'," and Eddie Floyd's "Raise Your Hand." Springsteen also performs fan favorite "Hard Times (Come Again No More)," written by Stephen Foster in 1854. Brian Fallon from The Gaslight Anthem joins the band as a guest vocalist on Springsteen's own "No Surrender." The concert earned rave reviews. -

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie Van Varik

BOBBY CHARLES LYRICS Compiled by Robin Dunn & Chrissie van Varik. Bobby Charles was born Robert Charles Guidry on 21st February 1938 in Abbeville, Louisiana. A native Cajun himself, he recalled that his life “changed for ever” when he re-tuned his parents’ radio set from a local Cajun station to one playing records by Fats Domino. Most successful as a songwriter, he is regarded as one of the founding fathers of swamp pop. His own vocal style was laidback and drawling. His biggest successes were songs other artists covered, such as ‘See You Later Alligator’ by Bill Haley & His Comets; ‘Walking To New Orleans’ by Fats Domino – with whom he recorded a duet of the same song in the 1990s – and ‘(I Don’t Know Why) But I Do’ by Clarence “Frogman” Henry. It allowed him to live off the songwriting royalties for the rest of his life! Two other well-known compositions are ‘The Jealous Kind’, recorded by Joe Cocker, and ‘Tennessee Blues’ which Kris Kristofferson committed to record. Disenchanted with the music business, Bobby disappeared from the music scene in the mid-1960s but returned in 1972 with a self-titled album on the Bearsville label on which he was accompanied by Rick Danko and several other members of the Band and Dr John. Bobby later made a rare live appearance as a guest singer on stage at The Last Waltz, the 1976 farewell concert of the Band, although his contribution was cut from Martin Scorsese’s film of the event. Bobby Charles returned to the studio in later years, recording a European-only album called Clean Water in 1987. -

Lyrics by Bill Ring

faithless angels Lyrics by Bill Ring faithless angels f Bill Ring & Ironwood a a 1. Nobody Wants a Wanted Man (2:35) Bill Ring - vocal, acoustic guitars, i 2. Ghost in the Road (4:03) harmonica, percussion n 3. Brave New World (4:42) Dave Redmond - electric guitar 4. Into the Shadows (6:02) Joe Crum - electric bass t 5. Waiting for Caligula (6:04) Angie Beeler - vocal (track 2-6, 8, 9, 11) g 6. Here for the Beer (3:12) Stacy Farina - vocal (track 1, 13) 7. House Money (4:17) Barry Miller - drums h 8. There Ain't No Train (5:49) Joey Dugan - flute e 9. Faithless Angels (5:20) Suzanne Schwartz - cello 10. Ride to California (4:23) l 11. I Just Can't Find the Blues (4:25) All songs written, arranged, and l 12. The End of History (2:15) mixed by Bill Ring 13. Cool to Black (6:01) e 14. The Lake (5:00) c P 2018 William G. Ring s Folksmith Visit www.folksmith.com s for pictures, lyrics, notes, and more on the songs and the artists. TM s All rights reserved by the copyright holder Permission to perform or record these songs will be given on request, but you must ask first. c P 2018 William G. Ring Brave New World - Bill Ring Page 1 of 2 I woke up this morning and I opened my eyes, Took a long look around and to my surprise, I don't know how and I don't know why, But I’m living in a brave new world. -

The B-Street Band Song List - Springsteen Songs

THE B-STREET BAND SONG LIST - SPRINGSTEEN SONGS THE RIVER THUNDER ROAD FOR YOU GROWING UP SHE'S THE ONE BORN TO RUN BRILLIANT DISGUISE DARLINGTON COUNTY HIGH HOPES BLINDED BY THE LIGHT SAINT IN THE CITY INDEPENDENCE DAY MEETING ACROSS RIVER POINT BLANK PROVE IT ALL NIGHT OUT IN THE STREET BADLANDS FIRE/I'M ON FIRE PROMISELAND CANDY'S ROOM BOBBY JEAN BORN IN THE USA COVER ME WORKING/HIGHWAY DOWNBOUND TRAIN GOIN' DOWN GLORY DAYS DANCING IN THE DARK ADAM RAISED THE CAIN SPIRIT IN THE NIGHT SANDY BACKSTREETS ROSALITA ALL OR NOTHING MAN'S JOB ROLL OF THE DICE BETTER DAYS LUCKY TOWN IF I SHOULD FALL BEHIND ATLANTIC CITY HUMAN TOUCH TUNNEL OF LOVE TIES THAT BIND HUNGRY HEART MY HOME TOWN STREETS OF PHILA RACING IN THE STREET 10TH AVENUE SHERRY DARLING JERSEY GIRL HEAVEN WILL ALLOW VIVA LAS VEGAS JUNGLELAND SANTA CLAUS BECAUSE THE NIGHT SOMETHING IN THE NIGHT NO SURRENDER TRAPPED YOU CAN LOOK DARKNESS ON THE EDGE MURDER INCORPORATED RAMROD NIGHT TWO HEARTS LOVE WON’T LET YOU DOWN THE RISING LONESOME DAY WAITIN ON A SUNNY DAY MARY’S PLACE LAND OF HOPE AND DREAMS PARADISE BY THE SEA MERRY XMAS BABY PAY ME MY MONEY DOWN E-STREET SHUFFLE RADIO NOWHERE LONG WALK HOME LIVIV IN THE FUTURE CADDILLAC RANCH WORK FOR YOUR LOVE GIRLS IN THEIR SUMMER PINK CADDILLAC SMALL THINGS MAMA QUARTER TO THREE AMERICAN LAND WRECKING BALL TAKE CARE OF OUR OWN FRANKIE FELL IN LOVE MEET ME IN THE CITY . -

Bruce Springsteen, Jungleland

Bruce Springsteen, Jungleland The rangers had a homecoming in Harlem late last night And the Magic Rat drove his sleek machine over the Jersey state line Barefoot girl sitting on the hood of a Dodge Drinking warm beer in the soft summer rain The Rat pulls into town rolls up his pants Together they take a stab at romance and disappear down Flamingo Lane Well the Maximum Lawman run down Flamingo chasing the Rat and the barefoot girl And the kids round here look just like shadows always quiet, holding hands From the churches to the jails tonight all is silence in the world As we take our stand down in Jungleland The midnight gang's assembled and picked a rendezvous for the night They'll meet `neath that giant Exxon sign that brings this fair city light Man there's an opera out on the Turnpike There's a ballet being fought out in the alley Until the local cops, Cherry Tops, rips this holy night The street's alive as secret debts are paid Contacts made, they vanished unseen Kids flash guitars just like switch-blades hustling for the record machine The hungry and the hunted explode into rock'n'roll bands That face off against each other out in the street down in Jungleland In the parking lot the visionaries dress in the latest rage Inside the backstreet girls are dancing to the records that the D.J. plays Lonely-hearted lovers struggle in dark corners Desperate as the night moves on, just a look and a whisper, and they're gone Beneath the city two hearts beat Soul engines running through a night so tender in a bedroom locked In whispers of