Tunisia | Freedom House: Freedom in the World 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L E M a G a Z I N E

LE MAGAZINE D E FRANCE IC PUBLICATIONS L’AFRIQUEoctobre - novembre 2015 | N° 45 609 Bât. A 77, RUE BAYEN 75017 PARIS EN COUVERTURE Tél : + 33 1 44 30 81 00 MAGHREB Fax : + 33 1 44 30 81 11 Courriel : [email protected] 4 LA DIPLOMATIE AFRICAINE www.magazinedelafrique.com ALGÉRIE DE LA FRANCE 50 Bouteflika-Mediène GRANDE-BRETAGNE 5 Hollande et l’Afrique La fin du bras de fer IC PUBLICATIONS 7 COLDBATH SQUARE 8 Les dessous de la nouvelle 53 Nouria Benghabrit, la ministre qui dérange LONDON EC1R 4LQ Tél : + 44 20 7841 32 10 approche française 54 Derrière la langue, l’idéologie Fax : + 44 20 7713 78 98 11 Les généraux « africains » à la manœuvre E.mail : [email protected] MAROC www.newafricanmagazine.com 13 Quels changements 56 Les élections locales confortent le PJD DIRECTEUR DE LA PUBLICATION dans la dépendance africaine ? Afif Ben Yedder TUNISIE ÉDITEUR 58 En quête de gouvernance Omar Ben Yedder 15 Le point de vue des journalistes DIRECTRICE GÉNÉRALE Serge Michel, Jean-Dominique Merchet, LIBYE Leila Ben Hassen [email protected] Malick Diawara, Frédéric Lejeal 60 Le kadhafisme est mort, RÉDACTEUR EN CHEF pas les kadhafistes Hichem Ben Yaïche ENTRETIENS [email protected] 18 Général Lamine Cissé AFRIQUE SUBSAHARIENNE COORDONNATEUR DE LA RÉDACTION La France n’a pas vocation de gendarme Junior Ouattara TCHAD 20 SECRÉTAIRE DE RÉDACTION Herman J. Cohen 62 La guerre intense contre Boko Haram Laurent Soucaille La collaboration est totale entre RÉDACTION la France et les États-Unis NIGER Christian d’Alayer, -

Forming the New Tunisian Government

Viewpoints No. 71 Forming the New Tunisian Government: “Relative Majority” and the Reality Principle Lilia Labidi Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center and former Minister for Women’s Affairs, Tunisia February 2015 After peaceful legislative and presidential elections in Tunisia toward the end of 2014, which were lauded on both the national and international levels, the attempt to form a new government reveals the tensions among the various political forces and the difficulties of constructing a democratic system in the country that was the birthplace of the "Arab Spring." Middle East Program 0 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ On January 23, 2015, Prime Minister Habib Essid announced the members of the new Tunisian government after much negotiation with the various political parties. Did Prime Minister Essid intend to give a political lesson to Tunisians, both to those who had been elected to the Assembly of the People’s Representatives (ARP) and to civil society? The ARP’s situation is worrisome for two reasons. First, 76 percent of the groups in political parties elected to the ARP have not submitted the required financial documents to the appropriate authorities in a timely manner. They therefore run the risk of losing their seats. Second, ARP members are debating the rules and regulations of the parliament as well as the definition of parliamentary opposition. They have been unable to reach an agreement on this last issue; without an agreement, the ARP is unable to vote on approval for a proposed government. There is conflict within a number of political parties in this context. In Nidaa Tounes, some members of the party, including MP Abdelaziz Kotti, have argued that there has been no exchange of information within the party regarding the formation of the government. -

Political Transition in Tunisia

Political Transition in Tunisia Alexis Arieff Analyst in African Affairs April 15, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21666 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Political Transition in Tunisia Summary On January 14, 2011, President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali fled the country for Saudi Arabia following weeks of mounting anti-government protests. Tunisia’s mass popular uprising, dubbed the “Jasmine Revolution,” appears to have added momentum to anti-government and pro-reform sentiment in other countries across the region, and some policy makers view Tunisia as an important “test case” for democratic transitions elsewhere in the Middle East. Ben Ali’s departure was greeted by widespread euphoria within Tunisia. However, political instability, economic crisis, and insecurity are continuing challenges. On February 27, amid a resurgence in anti-government demonstrations, Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi (a holdover from Ben Ali’s administration) stepped down and was replaced by Béji Caïd Essebsi, an elder statesman from the administration of the late founding President Habib Bourguiba. On March 3, the interim government announced a new transition “road map” that would entail the election on July 24 of a “National Constituent Assembly.” The Assembly would, in turn, be charged with promulgating a new constitution ahead of expected presidential and parliamentary elections, which have not been scheduled. The protest movement has greeted the road map as a victory, but many questions remain concerning its implementation. Until January, Ben Ali and his Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD) party exerted near-total control over parliament, state and local governments, and most political activity. -

Formations Politiques Du Sénat Sont Représentées

Groupe interparlementaire d’amitié France-Tunisie(1) Revenir en Tunisie Pour une reprise durable du tourisme en Tunisie et pour une coopération France-Tunisie en ce domaine Actes du colloque Sénat du 23 mars 2017 Sous le haut patronage de M. Gérard LARCHER, Président du Sénat Palais du Luxembourg Salle Clemenceau (1) Membres du groupe interparlementaire d’amitié France-Tunisie : M. Jean-Pierre SUEUR, Président, Mme Christiane KAMMERMANN, Vice-présidente, M. Claude KERN, Vice-président, M. Charles REVET, Vice-Président, M. Thierry CARCENAC, Secrétaire, Mme Laurence COHEN, Secrétaire, Mme Leila AÏCHI, Mme Éliane ASSASSI, Mme Esther BENBASSA, Mme Marie-Christine BLANDIN, M. Jean-Marie BOCKEL, Mme Corinne BOUCHOUX, M. Jean-Pierre CAFFET, M. Luc CARVOUNAS, M. Ronan DANTEC, Mme Annie DAVID, M. Vincent DELAHAYE, Mme Michelle DEMESSINE, Mme Josette DURRIEU, Mme Françoise FÉRAT, M. Jean-Jacques FILLEUL, M. Thierry FOUCAUD, M. Christophe-André FRASSA, M. Jean-Marc GABOUTY, M. Jean-Pierre GRAND, M. François GROSDIDIER, M. Charles GUENÉ, M. Loïc HERVÉ, M. Joël LABBÉ, M. Jean-Pierre LELEUX, M. Roger MADEC, Mme Catherine TASCA, M. Yannick VAUGRENARD, M. Jean-Pierre VIAL. _________________________________________ N° GA 145 – Mai 2017 - 3 - SOMMAIRE Pages AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................................................................... 5 OUVERTURE ........................................................................................................................... 7 Message de M. Gérard LARCHER, Président -

…De Patrimoine ? …De Guerre À La Corruption ?

…de patrimoine ? Déclaration… …de guerre à la corruption ? La déclaration de patrimoine en Tunisie, évaluation d’une politique publique Sous la direction de Mohamed HADDAD Tunis, juin 2018 La déclaration de patrimoine en Tunisie, évaluation d’une politique publique Présentation « Barr al Aman pour la recherche et les médias » est un média associatif tunisien qui vise à évaluer les politiques publiques notamment par des reportages, des interviews et des débats diffusés sur les réseaux sociaux ou sur les les ondes de la radio, mais aussi à travers des articles et rapports d’analyse. Cette organisation a été cofondée par Mohamed Haddad et Khansa Ben Tarjem à Tunis en 2015. Elle est financée par des contributions propres des membres mais aussi le soutien d’organismes internationaux comme l’organisation canadienne développement et paix, l’agence française de coopération médias – CFI et la délégation de l’Union Européenne en Tunisie. Les avis exprimés dans ce document sont ceux des auteurs et ne reflètent pas nécessairement les points de vue des partenaires techniques et financiers. Le nom de notre association « Barr al Aman » est un jeu de mots en arabe car lu rapidement, il devient « barlamane » ce qui veut dire parlement. Remerciements Merci à tous ceux qui ont contribué à ce rapport directement ou indirectement. Que ce soit pour la recherche, la saisie de données, les analyses, les relectures, corrections, traduction, conseils, etc. Merci particulièrement à BEN TARJEM Khansa, BOUHLEL Chaima, BEN YOUSSEF Mohamed Slim, CHEBAANE Imen, JAIDI Ali, ABDERRAHMANE Aymen, ALLANI Mohamed, MEZZI Rania, AROUS Hedia, BACHA Khaireddine, BENDANA KCHIR Kmar, BOUYSSY Maïté, KLAUS Enrique, TOUIHRI Aymen, SAIDANE Farouk, SILIANI Ghada, NAGUEZ Slim, NSIR Sarra, MERIAH Oussema, SBABTI Ihsen, LARBI Khalil, Pour citer ce rapport : La déclaration de patrimoine en Tunisie, évaluation d’une politique publique, Mohamed HADDAD (dir), Barr al Aman pour la recherche et les médias, Tunis, juin 2018. -

Nordafrikas Säkulare Zivilgesellschaften

NORDAFRIKAS SÄKULARE ZIVILGESELLSCHAFTEN IHR BEITRAG ZUR STÄRKUNG VON DEMOKRATIE UND MENSCHENRECHTEN SIGRID FAATH (HRSG.) NORDAFRIKAS SÄKULARE ZIVILGESELLSCHAFTEN NORDAFRIKAS SÄKULARE ZIVILGESELLSCHAFTEN IHR BEITRAG ZUR STÄRKUNG VON DEMOKRATIE UND MENSCHENRECHTEN Sigrid Faath (Hrsg.) Berlin, September 2016 © 2016, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e. V. unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. www.kas.de Satz: Rotkel Textwerkstatt, Berlin Umschlagfoto: Xavier Allard – Fotolia.com Die Publikation wurde gedruckt mit finanzieller Unterstützung der Bundes- republik Deutschland. ISBN 978-3-95721-214-6 INHALT 7 | VORWORT Hans-Gert Pöttering 11 | VORBEMERKUNG DER HERAUSGEBERIN Sigrid Faath 15 | NORDAFRIKAS ZIVILGESELLSCHAFTLICHE WEGBEREITER FÜR DEMOKRATIE UND PLURALISMUS: ZUM UNTERSUCHUNGSGEGENSTAND Sigrid Faath 29 | LÄNDERANALYSEN 31 | IN DER SACKGASSE: ÄGYPTENS MENSCHENRECHTSORGANISATIONEN IM VISIER DES SICHERHEITSSTAATES Jannis Grimm und Stephan Roll 53 | ALGERIENS SÄKULARE ZIVILGESELLSCHAFT: ZWISCHEN REFORMBEITRÄGEN UND SYSTEMERHALT Jasmin Lorch 85 | DIE SÄKULAREN ZIVILGESELLSCHAFTLICHEN ORGANISATIONEN IN LIBYEN SEIT 2011: ÜBERLEBEN IM CHAOS Ali Algibbeshi und Hanspeter Mattes 117 | MAROKKOS SÄKULARE ZIVILGESELLSCHAFT: VON DER VERFASSUNG GESTÄRKT, IN DER PRAXIS VOR EINER UNGEWISSEN -

Economic Will Be the Test of Tunisian Exceptionalism

CIDOB • Barcelona Centre for International for Affairs Centre CIDOB • Barcelona notesISSN: 2013-4428 internacionals CIDOB 109 ECONOMICS WILL BE THE TEST OF FEBRUARY TUNISIAN EXCEPTIONALISM 2015 Francis Ghilès, Senior Research Fellow, Barcelona Centre for International Affairs The challenges Tunisia has faced over the past four years have not gone away. Economic conditions have deteriorated. Getting the country back he revolts which star- to work, rebuilding the trust of the private sector, ensuring that public An encouraging start for investment is actually made, will be the acid test of whether Tunisia can the new leaders ted four years ago double its growth rate to 5-6% over the next few years. ushered in a pe- Triod of change in the Arab All the political nous the key actors in the presidency and government Mr Essebsi enjoyed a long world which has been can muster will be required if desperately needed jobs are to be created. career in the 1970s and 1980s Failure would spell social and political strife and an eventual reschedu- more violent and chaotic ling of foreign debt would impose its own cold logic. as minister of Foreign Affairs, that most observers fore- Defence and the Interior of saw. Syria is self-destruct- The private sector accounts for a paltry 20% of total investment. Half the founder of modern Tuni- ing. Libya is disintegrat- of the budgeted public sector investment has not been made since 2011. sia, Habib Bourguiba. He is Growth has been fuelled by private consumption, sucking in imports ing. Egypt has reverted to and not investment. -

Tunisia: in Brief

Tunisia: In Brief Updated July 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21666 Tunisia: In Brief Summary Tunisia has taken key steps toward democracy since its 2011 “Jasmine Revolution,” and has so far avoided the violent chaos and/or authoritarian resurrection seen elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa region. Tunisians adopted a new constitution in 2014 and held national elections the same year, marking the completion of a four-year transitional period. In May 2018, Tunisia held elections for newly created local government posts, a move toward political decentralization that activists and donors have long advocated. The government has also pursued gender equality reforms and enacted a law in 2017 to counter gender-based violence. Tunisians have struggled, however, to address steep economic challenges and overcome political infighting. Public opinion polls have revealed widespread anxiety about the future. Tunisia’s ability to counter terrorism appears to have improved since a string of large attacks in 2015-2016, although turmoil in neighboring Libya and the return of some Tunisian foreign fighters from Syria and Libya continue to pose threats. Militant groups also operate in Tunisia’s border regions. U.S. diplomatic contacts and aid have expanded significantly since 2011. President Trump spoke on the phone with Tunisian President Béji Caïd Essebsi soon after taking office in early 2017, and Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan visited Tunisia in November 2017. President Obama designated Tunisia a Major Non- North Atlantic Treaty Organization Ally in 2015 after meeting with President Caïd Essebsi at the White House. United States Aid for International Development opened an office in Tunis in 2014, reflecting increased bilateral economic aid allocations. -

The Initiators of the Arab Spring, Tunisia's Democratization Experience

The Initiators of the Arab Spring: Tunisia's Democratization Experience Uğur Pektaş Tunisia is seen as the birthplace of the Arab Spring, which is described as pro-democracy popular protests aimed at eliminating authoritarian governments in various Arab countries. The protests in Tunisia, which started with Mohamed Bouazizi's burning on December 17, 2010, ended without causing violence with the effect of Zine el Abidine Ben Ali’s departure from the country on January 14th. With its relatively low level of violence, Tunisia achieved the most successful outcome among the countries where the Arab Spring protests took place. In the decade after the authoritarian leader Ben Ali fled the country, significant progress has been made on the way to democracy in Tunisia. However, it can be said that the country's transition to democracy is still in limbo. Although 10 years have passed, Tunisians barely gained some political rights, but a backward economy and deterioration of the political fabric prevented these protests from reaching their goals. In the last 10 years, protesters took to the streets from time to time. If we take a general look at what happened in Tunisia in the last decade, it may be easier to understand the situation in question. An emergency was declared on January 14, 2011, following ongoing street protests. It has been announced that the government has dissolved and that general elections will be held within six months. Even this development did not end the protests and Ben Ali left the country. Fouad Mebazaa, the former spokesperson of the lower wing of the Tunisian Assembly, became the temporary president. -

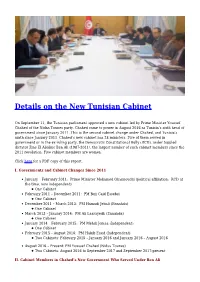

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet On September 11, the Tunisian parliament approved a new cabinet led by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed of the Nidaa Tounes party. Chahed came to power in August 2016 as Tunisia’s sixth head of government since January 2011. This is the second cabinet change under Chahed, and Tunisia’s ninth since January 2011. Chahed’s new cabinet has 28 ministers. Five of them served in government or in the ex-ruling party, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), under toppled dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (1987-2011), the largest number of such cabinet members since the 2011 revolution. Five cabinet members are women. Click here for a PDF copy of this report. I. Governments and Cabinet Changes Since 2011 January – February 2011: Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi (political affiliation: RCD at the time, now independent) One Cabinet February 2011 – December 2011: PM Beji Caid Essebsi One Cabinet December 2011 – March 2013: PM Hamadi Jebali (Ennahda) One Cabinet March 2013 – January 2014: PM Ali Laarayedh (Ennahda) One Cabinet January 2014 – February 2015: PM Mehdi Jomaa (Independent) One Cabinet February 2015 – August 2016: PM Habib Essid (Independent) Two Cabinets: February 2015 – January 2016 and January 2016 – August 2016 August 2016 – Present: PM Youssef Chahed (Nidaa Tounes) Two Cabinets: August 2016 to September 2017 and September 2017-present II. Cabinet Members in Chahed’s New Government Who Served Under Ben Ali Radhouane Ayara – Minister of Transportation Political affiliation: Nidaa Tounes New position, -

Political Transition in Tunisia

Political Transition in Tunisia Alexis Arieff Analyst in African Affairs Carla E. Humud Analyst in Middle Eastern and African Affairs February 10, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21666 Political Transition in Tunisia Summary Tunisia has taken key steps toward democracy since the “Jasmine Revolution” in 2011, and has so far avoided the violent chaos and/or authoritarian resurrection seen in other “Arab Spring” countries. Tunisians adopted a new constitution in January 2014 and held national elections between October and December 2014, marking the completion of a four-year transitional period. A secularist party, Nidaa Tounes (“Tunisia’s Call”), won a plurality of seats in parliament, and its leader Béji Caïd Essebsi was elected president. The results reflect a decline in influence for the country’s main Islamist party, Al Nahda (alt: Ennahda, “Awakening” or “Renaissance”), which stepped down from leading the government in early 2014. Al Nahda, which did not run a presidential candidate, nevertheless demonstrated continuing electoral appeal, winning the second-largest block of legislative seats and joining a Nidaa Tounes-led coalition government. Although many Tunisians are proud of the country’s progress since 2011, public opinion polls also show anxiety over the country’s future. Tangible improvements in the economy or government service-delivery are few, while security threats have risen. Nidaa Tounes leaders have pledged to improve counterterrorism efforts and boost economic growth, but have not provided many concrete details on how they will pursue these ends. The party may struggle to achieve internal consensus on specific policies, as it was forged from disparate groups united largely in their opposition to Islamism. -

Inside the Complexity of Iran-Tunisia Relations: Khomeinism, Bourguibism, Realpolitik

INSIDE THE COMPLEXITY OF About İRAM IRAN-TUNISIA RELATIONS: KHOMEINISM, BOURGUIBISM, dedicated to promoting innovative research and ideas on Iranian REALPOLITIK up-to-date and accurate knowledge about Iran’s politics, economy and society. İRAM’s research agenda is guided by three key princi ples – factuality, quality and responsibility. Hafssa Fakher El Abiari Oğuzlar Mh. 1397. Sk. No: 14 06520 Çankaya, Balgat, Ankara, Turkey Phone: +90 312 284 55 02 - 03 Fax: +90 312 284 55 04 e-mail: [email protected] www.iramcenter.org All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or Report November 2019 transmitted without the prior written permission of İRAM. © 2019 Center for Iranian Studies in Ankara (İRAM). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be fully reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published or broadcast without the prior written permission from İRAM. For electronic copies of this publication, visit iramcenter.org. Partial reproduction of the digital copy is possibly by giving an active link to www.iramcenter.org The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of İRAM, its staff, or its trustees. For electronic copies of this report, visit www. iramcenter.org. Editor : Jennifer Enzo Graphic Design : Hüseyin Kurt ISBN : Center for Iranian Studies in Ankara Oğuzlar, 1397. St, 06520, Çankaya, Ankara / Türkiye Phone: +90 (312) 284 55 02-03 | Fax: +90 (312) 284 55 04 e-mail : [email protected] | www.iramcenter.org Inside The Complexity Of Iran-Tunisia Relations: Khomeinism, Bourguibism, Realpolitik İran-Tunus İlişkilerindeki Karmaşikliğin İç Yüzü: Humeynicilik, Burgibacılık, Reel Politik بررسی ماهیت روابط ایران و تونس: خمینی گرایی، بورقیبه گرایی، سیاست واقع گرایانه Hafssa Fakher el Abiari Hafssa Fakher el Abiari is an International Relations student at Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane, Morocco.