Some Reflections on the Liberal Tradition in Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America

P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America LEE WARD Campion College University of Regina iii P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lee Ward 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lee, 1970– The politics of liberty in England and revolutionary America / Lee Ward p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn 0-521-82745-0 1. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 2. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 3. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 4. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 5. United States – History – Revolution, 1775–1783 – Causes. -

The Ojibwa: 1640-1840

THE OJIBWA: 1640-1840 TWO CENTURIES OF CHANGE FROM SAULT STE. MARIE TO COLDWATER/NARROWS by JAMES RALPH HANDY A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts P.JM'0m' Of. TRF\N£ }T:·mf.RRLAO -~ in Histor;y UN1V"RS1TY O " · Waterloo, Ontario, 1978 {§) James Ralph Handy, 1978 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. I authorize the University of Waterloo to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize the University of Waterloo to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the pur pose of scholarly research. 0/· (ii) The University of Waterloo requires the signature of all persons using or photo copying this thesis. Please sign below, and give address and date. (iii) TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1) Title Page (i) 2) Author's Declaration (11) 3) Borrower's Page (iii) Table of Contents (iv) Introduction 1 The Ojibwa Before the Fur Trade 8 - Saulteur 10 - growth of cultural affiliation 12 - the individual 15 Hurons 20 - fur trade 23 - Iroquois competition 25 - dispersal 26 The Fur Trade Survives: Ojibwa Expansion 29 - western villages JO - totems 33 - Midiwewin 34 - dispersal to villages 36 Ojibwa Expansion Into the Southern Great Lakes Region 40 - Iroquois decline 41 - fur trade 42 - alcohol (iv) TABLE OF CONTENTS (Cont'd) Ojibwa Expansion (Cont'd) - dependence 46 10) The British Trade in Southern -

Canada Needs You Volume One

Canada Needs You Volume One A Study Guide Based on the Works of Mike Ford Written By Oise/Ut Intern Mandy Lau Content Canada Needs You The CD and the Guide …2 Mike Ford: A Biography…2 Connections to the Ontario Ministry of Education Curriculum…3 Related Works…4 General Lesson Ideas and Resources…5 Theme One: Canada’s Fur Trade Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 2: Thanadelthur…6 Track 3: Les Voyageurs…7 Key Terms, People and Places…10 Specific Ministry Expectations…12 Activities…12 Resources…13 Theme Two: The 1837 Rebellion Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 5: La Patriote…14 Track 6: Turn Them Ooot…15 Key Terms, People and Places…18 Specific Ministry Expectations…21 Activities…21 Resources…22 Theme Three: Canadian Confederation Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 7: Sir John A (You’re OK)…23 Track 8: D’Arcy McGee…25 Key Terms, People and Places…28 Specific Ministry Expectations…30 Activities…30 Resources…31 Theme Four: Building the Wild, Wild West Songs: Lyrics and Description Track 9: Louis & Gabriel…32 Track 10: Canada Needs You…35 Track 11: Woman Works Twice As Hard…36 Key Terms, People and Places…39 Specific Ministry Expectations…42 Activities…42 Resources…43 1 Canada Needs You The CD and The Guide This study guide was written to accompany the CD “Canada Needs You – Volume 1” by Mike Ford. The guide is written for both teachers and students alike, containing excerpts of information and activity ideas aimed at the grade 7 and 8 level of Canadian history. The CD is divided into four themes, and within each, lyrics and information pertaining to the topic are included. -

Toronto Has No History!’

‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY By Victoria Jane Freeman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto ©Copyright by Victoria Jane Freeman 2010 ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ ABSTRACT ‘TORONTO HAS NO HISTORY!’ INDIGENEITY, SETTLER COLONIALISM AND HISTORICAL MEMORY IN CANADA’S LARGEST CITY Doctor of Philosophy 2010 Victoria Jane Freeman Graduate Department of History University of Toronto The Indigenous past is largely absent from settler representations of the history of the city of Toronto, Canada. Nineteenth and twentieth century historical chroniclers often downplayed the historic presence of the Mississaugas and their Indigenous predecessors by drawing on doctrines of terra nullius , ignoring the significance of the Toronto Purchase, and changing the city’s foundational story from the establishment of York in 1793 to the incorporation of the City of Toronto in 1834. These chroniclers usually assumed that “real Indians” and urban life were inimical. Often their representations implied that local Indigenous peoples had no significant history and thus the region had little or no history before the arrival of Europeans. Alternatively, narratives of ethical settler indigenization positioned the Indigenous past as the uncivilized starting point in a monological European theory of historical development. i i iii In many civic discourses, the city stood in for the nation as a symbol of its future, and national history stood in for the region’s local history. The national replaced ‘the Indigenous’ in an ideological process that peaked between the 1880s and the 1930s. -

Special Series on the Federal Dimensions of Reforming the Supreme Court of Canada

SPECIAL SERIES ON THE FEDERAL DIMENSIONS OF REFORMING THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA The Supreme Court of Canada: A Chronology of Change Jonathan Aiello Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University SC Working Paper 2011 21 May 1869 Intent on there being a final court of appeal in Canada following the Bill for creation of a Supreme country’s inception in 1867, John A. Macdonald, along with Court is withdrawn statesmen Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Mackenzie and Edward Blake propose a bill to establish the Supreme Court of Canada. However, the bill is withdrawn due to staunch support for the existing system under which disappointed litigants could appeal the decisions of Canadian courts to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) sitting in London. 18 March 1870 A second attempt at establishing a final court of appeal is again Second bill for creation of a thwarted by traditionalists and Conservative members of Parliament Supreme Court is withdrawn from Quebec, although this time the bill passed first reading in the House. 8 April 1875 The third attempt is successful, thanks largely to the efforts of the Third bill for creation of a same leaders - John A. Macdonald, Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Supreme Court passes Mackenzie and Edward Blake. Governor General Sir O’Grady Haly gives the Supreme Court Act royal assent on September 17th. 30 September 1875 The Honourable William Johnstone Ritchie, Samuel Henry Strong, The first five puisne justices Jean-Thomas Taschereau, Télesphore Fournier, and William are appointed to the Court Alexander Henry are appointed puisne judges to the Supreme Court of Canada. -

Proquest Dissertations

CSP-^ -OK2 1808 Anti-American and Loyalty Arguments In Toronto During the Federal Election Campaigns of 1872, 1874, and 1878 by Evan W. H. Brewer M. A. Thesis D ^& ^% , LitfRAftitS .> e*Sity o< ° Department of History Faculty of Graduate Studies University of Ottawa 1973 ^f\ EVHn'».B. Brewer, Ottawa, 1973. UMI Number: EC55459 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55459 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 i Acknowledgement This Thesis was prepared under the guidance of Professor Joseph Levitt, Department of History, University of Ottawa. ii Outline Page Introduction 1 Chapter I: The United States of America, The Imperial Tie, and the Dominion: Attitudes of Canadian Politicians 5 A. The Dominion and the United States of America ............ 5 B. The Dominion and the British Empire 12 C. The Dominion . 23 Chapter II: Election of 1872 25 Introduction 25 A. The Treaty of Washington in the Election 25 I. The Washington Conference and the Issues............ 25 II. -

Garofalo Book

Chapter 1 Introduction Fantasies of National Virility and William Wordsworth’s Poet Leader Violent Warriors and Benevolent Leaders: Masculinity in the Early Nineteenth-Century n 1822 British women committed a public act against propriety. They I commissioned a statue in honor of Lord Wellington, whose prowess was represented by Achilles, shield held aloft, nude in full muscular glory. Known as the “Ladies’ ‘Fancy Man,’” however, the statue shocked men on the statue committee who demanded a fig leaf to protect the public’s out- raged sensibilities.1 Linda Colley points to this comical moment in postwar British history as a sign of “the often blatantly sexual fantasies that gathered around warriors such as Nelson and Wellington.”2 However, the statue in its imitation of a classical aesthetic necessarily recalled not only the thrilling glory of Great Britain’s military might, but also the appeal of the defeated but still fascinating Napoleon. After all, the classical aesthetic was central to the public representation of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic regimes. If a classical statue was supposed to apotheosize Wellington, it also inevitably spoke to a revolutionary and mar- tial manhood associated with the recently defeated enemy. Napoleon him- self had commissioned a nude classical statue from Canova that Marie Busco speculates “would have been known” to Sir Richard Westmacott, who cast the bronze Achilles. In fact Canova’s Napoleon was conveniently located in the stairwell of Apsley House after Louis XVIII presented it to the Duke of Wellington.3 These associations with Napoleon might simply have underscored the British superiority the Wellington statue suggested. -

The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns

Choice or Consensus?: The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns Jared J. Wesley PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Calgary Paper for Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan May 30, 2007 Comments welcome. Please do not cite without permission. CHOICE OR CONSENSUS?: THE 2006 FEDERAL LIBERAL AND ALBERTA CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGNS INTRODUCTION Two of Canada’s most prominent political dynasties experienced power-shifts on the same weekend in December 2006. The Liberal Party of Canada and the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta undertook leadership campaigns, which, while different in context, process and substance, produced remarkably similar outcomes. In both instances, so-called ‘dark-horse’ candidates emerged victorious, with Stéphane Dion and Ed Stelmach defeating frontrunners like Michael Ignatieff, Bob Rae, Jim Dinning, and Ted Morton. During the campaigns and since, Dion and Stelmach have been labeled as less charismatic than either their predecessors or their opponents, and both of the new leaders have drawn skepticism for their ability to win the next general election.1 This pair of surprising results raises interesting questions about the nature of leadership selection in Canada. Considering that each race was run in an entirely different context, and under an entirely different set of rules, which common factors may have contributed to the similar outcomes? The following study offers a partial answer. In analyzing the platforms of the major contenders in each campaign, the analysis suggests that candidates’ strategies played a significant role in determining the results. Whereas leading contenders opted to pursue direct confrontation over specific policy issues, Dion and Stelmach appeared to benefit by avoiding such conflict. -

University of Toronto Archives George Mackinnon

University of Toronto Archives and Record Management Services Finding Aid – George M. Wrong Family fonds Contains the following accessions: • B1980-0019 • B2003-0005 • B2004-0010 • B2006-0001 Wrong Family B1980-0019 Item No. Title and/or subject Date Size (cm) Photographer :0001 The prep school, Upper Canada College, when Humphrey Hume Wrong n.d. 24 x 19 Galbraith Photo Co., was there Toronto :0002 The prep school, Upper Canada College, when Humphrey Hume Wrong n.d. 24 x 19 was there :0003 Harold Verschoyle Wrong with his company of Lancashire Fusiliers at 1914 or 1915 28 x 23 Conway, Wales :0004 The Officers, 15th (Service) Battalion (1st Salford) Lancashire Fusiliers. 1915 29 x 17 Gale & Polden Ltd., Morfa Camp, Conway, Wales, 1915; 2nd-Lt. H. V. Wrong is present Aldershort :0005 University College Dinner Committee, 1910-1911, includes Edward 1911 35 x 27 Park Bros., Toronto Murray Wrong :0006 "The Varsity", 1882-1883. Includes George MacKinnon Wrong 1883 33 x 24 :0007 Students of Wycliffe College, 1885-86 1886 34 x 23 Stanton, Toronto :0008 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. H. Wrong and H. V. Wrong [ca. 1911-1913] 32 x 42 Park Bros., Toronto :0009 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. V. Wrong [ca. 1909-1911] 32 x 41 Park Bros., Toronto :0010 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. H. Wrong and H. V. Wrong [ca. 1911-1913] 30 x 42 Park Bros., Toronto :0011 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. V. Wrong [ca. 1909-1911] 30 x 42 Park Bros., Toronto :0012 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. -

History 3231F

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Autumn 2012 HISTORY 3231F “Yours to Discover”: A History of Ontario Roger Hall Time: Wed” 1:30-3:30 Lawson Hall 2228 Place: STVH 2166 [email protected] The course is a survey of Ontario’s rich and varied past commencing with its founding as the colony of Upper Canada in the aftermath of the American Revolution and stretching to the modern day. Conducted in the form of a workshop with instructor and students both participating, a chronological frame is followed although individual sessions will pursue separate themes revealing the changing politics, society and economy. Each session, of which there will be two per weekly meeting, will include a brief introduction to the topic by the instructor, and then a verbal report prepared by a student, followed by questions and discussion. Assigned readings should make the discussion informative. Readings will be from prescribed texts, internet and library sources and handouts. There will be no mid-terms in this course. Reports will be made by students throughout the course; the essay themes can be the same as the reports—needless to say a superior performance will be expected in written work. There will be ONE essay and a final examination. GRADE BREAKDOWN Reports: 30% General Class Participation: 20% Essay 25% Final Exam 25% TEXTS: Randall White, Ontario, 1610-1985 (Toronto, Dundurn Press). Edgar-Andre Montigny and Lori Chambers, Ontario since Confederation, A Reader (Toronto, University of Toronto Press) R. Hall, W. Westfall and L. Sefton MacDowell, Patterns of the Past: Interpreting Ontario’s History (Toronto, Dundurn Press). -

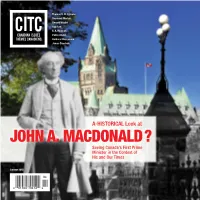

JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times

Thomas H. B. Symons Desmond Morton Donald Wright Bob Rae E. A. Heaman Patrice Dutil Barbara Messamore James Daschuk A-HISTORICAL Look at JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times Summer 2015 Introduction 3 Macdonald’s Makeover SUMMER 2015 Randy Boswell John A. Macdonald: Macdonald's push for prosperity 6 A Founder and Builder 22 overcame conflicts of identity Thomas H. B. Symons E. A. Heaman John Alexander Macdonald: Macdonald’s Enduring Success 11 A Man Shaped by His Age 26 in Quebec Desmond Morton Patrice Dutil A biographer’s flawed portrait Formidable, flawed man 14 reveals hard truths about history 32 ‘impossible to idealize’ Donald Wright Barbara Messamore A time for reflection, Acknowledging patriarch’s failures 19 truth and reconciliation 39 will help Canada mature as a nation Bob Rae James Daschuk Canadian Issues is published by/Thèmes canadiens est publié par Canada History Fund Fonds pour l’histoire du Canada PRÉSIDENT/PResIDENT Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens is a quarterly publication of the Association for Canadian Jocelyn Letourneau, Université Laval Studies (ACS). It is distributed free of charge to individual and institutional members of the ACS. INTRODUCTION PRÉSIDENT D'HONNEUR/HONORARY ChaIR Canadian Issues is a bilingual publication. All material prepared by the ACS is published in both The Hon. Herbert Marx French and English. All other articles are published in the language in which they are written. SecRÉTAIRE DE LANGUE FRANÇAISE ET TRÉSORIER/ MACDONALd’S MAKEOVER FRENch-LaNGUAGE SecRETARY AND TReasURER Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Vivek Venkatesh, Concordia University the ACS. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... ..........................................................................