Canada's Foundations and Their Consequences 1865

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Series on the Federal Dimensions of Reforming the Supreme Court of Canada

SPECIAL SERIES ON THE FEDERAL DIMENSIONS OF REFORMING THE SUPREME COURT OF CANADA The Supreme Court of Canada: A Chronology of Change Jonathan Aiello Institute of Intergovernmental Relations School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University SC Working Paper 2011 21 May 1869 Intent on there being a final court of appeal in Canada following the Bill for creation of a Supreme country’s inception in 1867, John A. Macdonald, along with Court is withdrawn statesmen Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Mackenzie and Edward Blake propose a bill to establish the Supreme Court of Canada. However, the bill is withdrawn due to staunch support for the existing system under which disappointed litigants could appeal the decisions of Canadian courts to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) sitting in London. 18 March 1870 A second attempt at establishing a final court of appeal is again Second bill for creation of a thwarted by traditionalists and Conservative members of Parliament Supreme Court is withdrawn from Quebec, although this time the bill passed first reading in the House. 8 April 1875 The third attempt is successful, thanks largely to the efforts of the Third bill for creation of a same leaders - John A. Macdonald, Télesphore Fournier, Alexander Supreme Court passes Mackenzie and Edward Blake. Governor General Sir O’Grady Haly gives the Supreme Court Act royal assent on September 17th. 30 September 1875 The Honourable William Johnstone Ritchie, Samuel Henry Strong, The first five puisne justices Jean-Thomas Taschereau, Télesphore Fournier, and William are appointed to the Court Alexander Henry are appointed puisne judges to the Supreme Court of Canada. -

Discover Canada the Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE Discover Canada The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship 2 Your Canadian Citizenship Study Guide Message to Our Readers The Oath of Citizenship Le serment de citoyenneté Welcome! It took courage to move to a new country. Your decision to apply for citizenship is Je jure (ou j’affirme solennellement) another big step. You are becoming part of a great tradition that was built by generations of pioneers I swear (or affirm) Que je serai fidèle before you. Once you have met all the legal requirements, we hope to welcome you as a new citizen with That I will be faithful Et porterai sincère allégeance all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. And bear true allegiance à Sa Majesté la Reine Elizabeth Deux To Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second Reine du Canada Queen of Canada À ses héritiers et successeurs Her Heirs and Successors Que j’observerai fidèlement les lois du Canada And that I will faithfully observe Et que je remplirai loyalement mes obligations The laws of Canada de citoyen canadien. And fulfil my duties as a Canadian citizen. Understanding the Oath Canada has welcomed generations of newcomers Immigrants between the ages of 18 and 54 must to our shores to help us build a free, law-abiding have adequate knowledge of English or French In Canada, we profess our loyalty to a person who represents all Canadians and not to a document such and prosperous society. For 400 years, settlers in order to become Canadian citizens. You must as a constitution, a banner such as a flag, or a geopolitical entity such as a country. -

Proquest Dissertations

CSP-^ -OK2 1808 Anti-American and Loyalty Arguments In Toronto During the Federal Election Campaigns of 1872, 1874, and 1878 by Evan W. H. Brewer M. A. Thesis D ^& ^% , LitfRAftitS .> e*Sity o< ° Department of History Faculty of Graduate Studies University of Ottawa 1973 ^f\ EVHn'».B. Brewer, Ottawa, 1973. UMI Number: EC55459 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55459 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 i Acknowledgement This Thesis was prepared under the guidance of Professor Joseph Levitt, Department of History, University of Ottawa. ii Outline Page Introduction 1 Chapter I: The United States of America, The Imperial Tie, and the Dominion: Attitudes of Canadian Politicians 5 A. The Dominion and the United States of America ............ 5 B. The Dominion and the British Empire 12 C. The Dominion . 23 Chapter II: Election of 1872 25 Introduction 25 A. The Treaty of Washington in the Election 25 I. The Washington Conference and the Issues............ 25 II. -

The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns

Choice or Consensus?: The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns Jared J. Wesley PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Calgary Paper for Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan May 30, 2007 Comments welcome. Please do not cite without permission. CHOICE OR CONSENSUS?: THE 2006 FEDERAL LIBERAL AND ALBERTA CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGNS INTRODUCTION Two of Canada’s most prominent political dynasties experienced power-shifts on the same weekend in December 2006. The Liberal Party of Canada and the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta undertook leadership campaigns, which, while different in context, process and substance, produced remarkably similar outcomes. In both instances, so-called ‘dark-horse’ candidates emerged victorious, with Stéphane Dion and Ed Stelmach defeating frontrunners like Michael Ignatieff, Bob Rae, Jim Dinning, and Ted Morton. During the campaigns and since, Dion and Stelmach have been labeled as less charismatic than either their predecessors or their opponents, and both of the new leaders have drawn skepticism for their ability to win the next general election.1 This pair of surprising results raises interesting questions about the nature of leadership selection in Canada. Considering that each race was run in an entirely different context, and under an entirely different set of rules, which common factors may have contributed to the similar outcomes? The following study offers a partial answer. In analyzing the platforms of the major contenders in each campaign, the analysis suggests that candidates’ strategies played a significant role in determining the results. Whereas leading contenders opted to pursue direct confrontation over specific policy issues, Dion and Stelmach appeared to benefit by avoiding such conflict. -

20-4.4 Canadian National Identity

20-4.4 Canadian National Identity National Identity 1. Survey your classmates to find out what being Canadian means to them. Fill out the organizer below. Student’s Name What being a Canadian means to him or her: Share your answers with classmates and create a class poster that illustrates what being Canadian means to students in your class. Knowledge and Employability Studio Social Studies 20-4.4 Canadian National Identity ©Alberta Education, April 2019 (www.LearnAlberta.ca) National Identity 1/11 2. Did the people in your class express different points of view on Canadian identity? Your culture and personal experiences may affect your perspective on what it means to be Canadian. Find out how the different types of Canadians below feel about Canadian identity and fill in the diagram with key words that describe their feelings. First Nations French New Canadians Immigrants Canadian Identity Urban Descendants Dwellers of European Settlers Rural Dwellers Knowledge and Employability Studio Social Studies 20-4.4 Canadian National Identity ©Alberta Education, April 2019 (www.LearnAlberta.ca) National Identity 2/11 3. Choose one of the groups from the previous Use these tools: question or another group and conduct a more thorough investigation of how people in that Getting Started with Research group feel about Canadian identity. Create a Recording Information simple presentation of your findings. If possible, include interviews and quotes. 4. To better understand symbols that promote a collective identity in Canada, follow these steps. Step one: Explain the history and importance of the following symbols of Canadian national identity. The Canadian Coat of Arms The Canadian Flag (Maple Leaf) The Canadian National Anthem (O Canada) Step two: Identify 10 Where to Start on the Web other symbols that promote Canadian https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian- identity and what each heritage/services/official-symbols-canada.html represents. -

University of Toronto Archives George Mackinnon

University of Toronto Archives and Record Management Services Finding Aid – George M. Wrong Family fonds Contains the following accessions: • B1980-0019 • B2003-0005 • B2004-0010 • B2006-0001 Wrong Family B1980-0019 Item No. Title and/or subject Date Size (cm) Photographer :0001 The prep school, Upper Canada College, when Humphrey Hume Wrong n.d. 24 x 19 Galbraith Photo Co., was there Toronto :0002 The prep school, Upper Canada College, when Humphrey Hume Wrong n.d. 24 x 19 was there :0003 Harold Verschoyle Wrong with his company of Lancashire Fusiliers at 1914 or 1915 28 x 23 Conway, Wales :0004 The Officers, 15th (Service) Battalion (1st Salford) Lancashire Fusiliers. 1915 29 x 17 Gale & Polden Ltd., Morfa Camp, Conway, Wales, 1915; 2nd-Lt. H. V. Wrong is present Aldershort :0005 University College Dinner Committee, 1910-1911, includes Edward 1911 35 x 27 Park Bros., Toronto Murray Wrong :0006 "The Varsity", 1882-1883. Includes George MacKinnon Wrong 1883 33 x 24 :0007 Students of Wycliffe College, 1885-86 1886 34 x 23 Stanton, Toronto :0008 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. H. Wrong and H. V. Wrong [ca. 1911-1913] 32 x 42 Park Bros., Toronto :0009 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. V. Wrong [ca. 1909-1911] 32 x 41 Park Bros., Toronto :0010 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. H. Wrong and H. V. Wrong [ca. 1911-1913] 30 x 42 Park Bros., Toronto :0011 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. Includes H. V. Wrong [ca. 1909-1911] 30 x 42 Park Bros., Toronto :0012 Kappa Alpha Fraternity, n.d. -

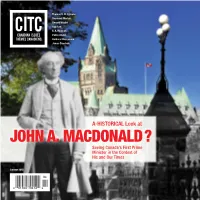

JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times

Thomas H. B. Symons Desmond Morton Donald Wright Bob Rae E. A. Heaman Patrice Dutil Barbara Messamore James Daschuk A-HISTORICAL Look at JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times Summer 2015 Introduction 3 Macdonald’s Makeover SUMMER 2015 Randy Boswell John A. Macdonald: Macdonald's push for prosperity 6 A Founder and Builder 22 overcame conflicts of identity Thomas H. B. Symons E. A. Heaman John Alexander Macdonald: Macdonald’s Enduring Success 11 A Man Shaped by His Age 26 in Quebec Desmond Morton Patrice Dutil A biographer’s flawed portrait Formidable, flawed man 14 reveals hard truths about history 32 ‘impossible to idealize’ Donald Wright Barbara Messamore A time for reflection, Acknowledging patriarch’s failures 19 truth and reconciliation 39 will help Canada mature as a nation Bob Rae James Daschuk Canadian Issues is published by/Thèmes canadiens est publié par Canada History Fund Fonds pour l’histoire du Canada PRÉSIDENT/PResIDENT Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens is a quarterly publication of the Association for Canadian Jocelyn Letourneau, Université Laval Studies (ACS). It is distributed free of charge to individual and institutional members of the ACS. INTRODUCTION PRÉSIDENT D'HONNEUR/HONORARY ChaIR Canadian Issues is a bilingual publication. All material prepared by the ACS is published in both The Hon. Herbert Marx French and English. All other articles are published in the language in which they are written. SecRÉTAIRE DE LANGUE FRANÇAISE ET TRÉSORIER/ MACDONALd’S MAKEOVER FRENch-LaNGUAGE SecRETARY AND TReasURER Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Vivek Venkatesh, Concordia University the ACS. -

5 Confederation Won Celebration!

063-073 120820 11/1/04 2:34 PM Page 63 Chapter 5 Confederation Won Celebration! With the first dawn of this summer morn- mourning. A likeness of Dr. Tupper is burned ing, we hail the birthday of a new nation. side-by-side with a rat in Nova Scotia. In A united British America takes its place New Brunswick, a newspaper carries a death among the nations of the world. notice on its front page: “Died—at her resi- dence in the city of Fredericton, The Prov- —George Brown ince of New Brunswick, in the 83rd year of her age.” It is 1 July 1867. The church bells start to ring at midnight. Early in the morning guns roar a salute from Halifax in the east to Sarnia in the west. Bonfires and fireworks light up the sky in cities and towns across the new country. It is the birthday of the new Dominion of Canada and the people of Ontario, Québec, New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia are cele- brating. Under blue skies and sunshine, people of all religious faiths gather to offer prayers for the future of the nation. In Toronto, there is a great celebration at the Horticultural Gardens. The gardens are lit with Chinese lanterns. Fresh strawberries and ice cream are served. A concert is followed by dancing. Tickets are 25¢; children’s tickets are 10¢. In another part of the city, a huge ox is roasted and the meat is distributed to the poor. In Québec, boat races on the river, horse races, and a cricket match are held. -

209 AMENDING the BRITISH NORTH AMERICA ACT. Every

209 AMENDING THE BRITISH NORTH AMERICA ACT. Every Canadian should be inspired by the vision of the Fathers of Confederation in their conception of one vast nation of the British Provinces in North America, stretching from sea to sea, and by the ability and courage they displayed in putting their patriotic vision into practical effect. But the B .N.A. Act makes no special provision for its amendment and the suggestion is sometimes made that this point was overlooked. I believe the Fathers of Confederation assumed that any amendments to the Act would, as the occasion arose, be made by the Imperial Parliament . I can find no reference in pre-Confederation speeches to the amendment of the proposed Act, except that in the debates of the Canadian Parliament of 1865 the Hon . D'Arcy McGee said :- "We go to the Imperial Government, the common arbiter of us all, in our true Federal metropolis-we go there to ask for our fundamental Charter. We hope, by having that Charter can that only be amended by the authority that made it, that we will lay the basis of permanency for our future government." -"Canada Confederation Debates", (1865) page 146. There is a very substantial part of the Canadian Constitution outside the B.N.A. Act, which, following British precedent, grows. and develops. The B .N.A. Act, however, can only be amended by statute and, defining as it does the legislative power of the Dominion and provinces respectively, the question as to how it should be amended has of late years become a matter of increasing importance . -

“Pistol Fever”: Regulating Revolvers in Late-Nineteenth-Century Canada"

Article "“Pistol Fever”: Regulating Revolvers in Late-Nineteenth-Century Canada" Blake Brown Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, vol. 20, n° 1, 2009, p. 107-138. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/039784ar DOI: 10.7202/039784ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 12 février 2017 11:48 “Pistol fever”: Regulating Revolvers in Late- nineteenth-Century Canada BLAkE BROwn* Abstract This paper examines the debates over the regulation of pistols in Canada from confederation to the passage of nation’s first Criminal Code in 1892. It demon- strates that gun regulation has long been an important and contentious issue in Canada. Cheap revolvers were deemed a growing danger by the 1870s. A per- ception emerged that new forms of pistols increased the number of shooting accidents, encouraged suicide, and led to murder. -

The Day of Sir John Macdonald – a Chronicle of the First Prime Minister

.. CHRONICLES OF CANADA Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton In thirty-two volumes 29 THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD BY SIR JOSEPH POPE Part VIII The Growth of Nationality SIR JOHX LIACDONALD CROSSING L LALROLAILJ 3VER TIIE XEWLY COSSTRUC CANADI-IN P-ICIFIC RAILWAY, 1886 From a colour drawinrr bv C. \TT. Tefferv! THE DAY OF SIR JOHN MACDONALD A Chronicle of the First Prime Minister of the Dominion BY SIR JOSEPH POPE K. C. M. G. TORONTO GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY 1915 PREFATORY NOTE WITHINa short time will be celebrated the centenary of the birth of the great statesman who, half a century ago, laid the foundations and, for almost twenty years, guided the destinies of the Dominion of Canada. Nearly a like period has elapsed since the author's Memoirs of Sir John Macdonald was published. That work, appearing as it did little more than three years after his death, was necessarily subject to many limitations and restrictions. As a connected story it did not profess to come down later than the year 1873, nor has the time yet arrived for its continuation and completion on the same lines. That task is probably reserved for other and freer hands than mine. At the same time, it seems desirable that, as Sir John Macdonald's centenary approaches, there should be available, in convenient form, a short r6sum6 of the salient features of his vii viii SIR JOHN MACDONALD career, which, without going deeply and at length into all the public questions of his time, should present a familiar account of the man and his work as a whole, as well as, in a lesser degree, of those with whom he was intimately associated. -

Monday, April 10, 2000

CANADA 2nd SESSION • 36th PARLIAMENT • VOLUME 138 • NUMBER 46 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, April 10, 2000 THE HONOURABLE GILDAS L. MOLGAT SPEAKER CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue.) Debates: Chambers Building, Room 943, Tel. 996-0193 Published by the Senate Available from Canada Communication Group — Publishing, Public Works and Government Services Canada, Ottawa K1A 0S9, Also available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1057 THE SENATE Monday, April 10, 2000 The Senate met at 4:00 p.m., the Speaker in the Chair. He is equally familiar with the economic engine of Saskatchewan, namely, the agricultural industry. When he said Prayers. that agriculture was something he had done all his life, he was not exaggerating. Senator Wiebe is a long-time farmer. He has NEW SENATORS been very involved with the cooperative movement and has served on the Main Center Wheat Pool Committee, the Herbert The Hon. the Speaker: Honourable senators, I have the Credit Union, the Herbert Co-op, and the Saskatchewan honour to inform the Senate that the Clerk has received Co-operative Advisory Board. From 1970 to 1986, he was owner certificates from the Registrar General of Canada showing that and president of L&W Feeders Ltd. the following persons, respectively, have been summoned to the Senate: His personal success, balanced with a strong commitment of public service to his province and to his community, has made John Edward Neil Wiebe Senator Wiebe sensitive to the aspirations and challenges of Thomas Benjamin Banks, O.C. fellow citizens. As Premier Romanow said earlier this year: INTRODUCTION Jack Wiebe has a tremendous capacity to relate to the everyday issues and concerns of the people of this province.