Garofalo Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America

P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 The Politics of Liberty in England and Revolutionary America LEE WARD Campion College University of Regina iii P1: IwX/KaD 0521827450agg.xml CY395B/Ward 0 521 82745 0 May 7, 2004 7:37 published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge cb2 2ru, uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Lee Ward 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typeface Sabon 10/12 pt. System LATEX 2ε [tb] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ward, Lee, 1970– The politics of liberty in England and revolutionary America / Lee Ward p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. isbn 0-521-82745-0 1. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 2. Political science – Great Britain – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 3. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 17th century. 4. Political science – United States – Philosophy – History – 18th century. 5. United States – History – Revolution, 1775–1783 – Causes. -

Deification in the Early Century

chapter 1 Deification in the early century ‘Interesting, dignified, and impressive’1 Public monuments were scarce in Ireland at the begin- in 7 at the expense of Dublin Corporation, was ning of the nineteenth century and were largely con- carefully positioned on a high pedestal facing the seat fined to Dublin, which boasted several monumental of power in Dublin Castle, and in close proximity, but statues of English rulers, modelled in a weighty and with its back to the seat of learning in Trinity College. pompous late Baroque style. Cork had an equestrian A second equestrian statue, a portrait of George I by statue of George II, by John van Nost, the younger (fig. John van Nost, the elder (d.), was originally placed ), positioned originally on Tuckey’s Bridge and subse- on Essex Bridge (now Capel Street Bridge) in . It quently moved to the South Mall in .2 Somewhat was removed in , and was re-erected at the end of more unusually, Birr, in County Offaly, featured a sig- the century, in ,8 in the gardens of the Mansion nificant commemoration of Prince William Augustus, House, facing out over railings towards Dawson Street. Duke of Cumberland (–) (fig. ). Otherwise The pedestal carried the inscription: ‘Be it remembered known as the Butcher of Culloden,3 he was com- that, at the time when rebellion and disloyalty were the memorated by a portrait statue surmounting a Doric characteristics of the day, the loyal Corporation of the column, erected in Emmet Square (formerly Cumber- City of Dublin re-elevated this statue of the illustrious land Square) in .4 The statue was the work of House of Hanover’.9 A third equestrian statue, com- English sculptors Henry Cheere (–) and his memorating George II, executed by the younger John brother John (d.). -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

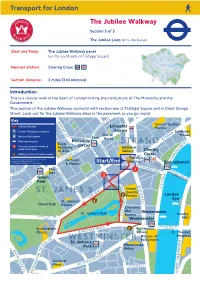

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

History of Britain from the Restoration to 1783

History of Britain from the Restoration to 1783 HIS 334J (39130) & EUS 346 (36220) Fall Semester 2018 Charles II of England in Coronation Robes Pulling Down the Statue of George III at Bowling John Michael Wright, c. 1661-1662 Green in Lower Manhattan William Walcutt, 1857 ART 1.110 Tuesday & Thursday, 12:30 – 2:00 PM Instructor James M. Vaughn [email protected] Office: Garrison 3.218 (ph. 512-232-8268) Office Hours: Friday, 2:30 – 4:30 PM, and by appointment Course Description This lecture course surveys the history of England and, after the union with Scotland in 1707, the history of Great Britain from the English Revolution and the restoration of the Stuart monarchy (c. 1640-1660) to the War of American Independence (c. 1775-1783). The kingdom underwent a remarkable transformation during this period, with a powerful monarchy, a persecuting state church, a traditional society, and an agrarian economy giving way to parliamentary rule, religious toleration, a dynamic civil society, and a commercial and manufacturing-based economy on the eve of industrialization. How and why did this transformation take place? Over the course of the same period, Great Britain emerged as a leading European and world power with a vast commercial and territorial empire stretching across four continents. How and why did this island kingdom off the northwestern coast of Europe, geopolitically insignificant for much of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, become a Great Power and acquire a global empire in the 1 eighteenth century? How did it do so while remaining a free and open society? This course explores these questions as well as others. -

Is the History of Science Essentially Whiggish?

Hist. Sci., li (2013) IS THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE ESSENTIALLY WHIGGISH? David Alvargonzález University of Oviedo 1. THE STIGMATIC LABEL OF ‘WHIGGISM’ In his influential 1931essay The Whig interpretation of history, Herbert Butterfield criticized what he called the “Whig history”, the “study of the past for the sake of the present”; history, he stated, cannot be used to justify certain contents in the present. In particular, he denounced conceiving of history as a succession of goal-directed stages, such that past stages must be seen through the lens of their future goal. As his account goes, any investigation into the causes of historical change is hampered by anachronism, while any teleological, goal-directed narrative proves untenable. Butterfield, in the face of Whig historians, rather preferred an ideal whereby the past be studied “for the sake of the past”,1 whereby the historian become more than a mere observer and one who actually “goes out to meet the past”.2 Chief in the reticle of Butterfield’s book was the political history of the circum- stances leading to the Protestant Reformation and the modern constitution of the English people. There, he contradistinguished Whig history, which understood the Reformation as an inevitable step towards progress, from the Catholic, Tory inter- pretation of the same event; for Butterfield, Luther was nothing of a progressive. Whiggism, for him, was inherently related to what he called “abridged” or “general history” itself rectified, so to speak, by a specialized, technical history of very con- crete, detailed issues. Around the same time as Butterfield, Alexandre Koyré published his well-known Études galiléennes in the field of the history of science.3 In these important essays, Galileo takes shape less as a modern experimentalist (as a hagiographic present- centred history would have it) and more as a speculative Platonist seeking to refute Aristotelianism. -

Childish Ways: Anne Damer and Other Precursors to Childe Harold's

1 CHILDISH WAYS : ANNE DAMER AND OTHER PRECURSORS TO CHILDE HAROLD ’S PILGRIMAGE JONATHAN GROSS DE PAUL UNIVERSITY How did Anne Damer and William Beckford anticipate, and in a sense make possible, Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage ? A brief overview of these Byron precursors might be helpful. In 1787, William Beckford (author of Vathek) visited Lisbon as a social outcast after his reputed affair with William Courtenay in the Powderham scandal; he struggled unsuccessfully to be admitted to the King and Queen of Portugal and kept a journal recounting the events. Four years later, in 1791, Anne Damer arrived in the same city to recover her health. Her husband had committed suicide in 1776 and she lived a precarious life as an amateur actress, sculptress, and novelist. In fact, she wrote the rough draft of Belmour (1801) during her stay. In 1808, Byron had to consider whether he would be a politician (potentially a soldier), or a writer when he came to Lisbon. Though he had written several poems, they had received mixed reviews, and it was not clear whether Byron would ever mature successfully from the poetic persona he had established in Fugitive Pieces , Hours of Idleness , and English Bards and Scotch Reviewers . When he began the poem that made him famous in Cintra at the St. Lawrence hotel, Byron’s future was not firmly established. All three figures, Beckford, Damer, and Byron, viewed Portugal and Cintra, as places to recover their lost youth, and to celebrate the creative values associated with childishness which they explored in their art, whether in Vathek , Belmour , or Childe Harold . -

Stuart Debauchery in Restoration Satire

Stuart Debauchery in Restoration Satire Neal Hackler A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the PhD degree in English Supervised by Dr. Nicholas von Maltzahn Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Neal Hackler, Ottawa, Canada, 2015. ii Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ iii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures and Illustrations.............................................................................................v List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................... vi Note on Poems on Affairs of State titles ............................................................................. vii Stuart Debauchery in Restoration Satire Introduction – Making a Merry Monarch...................................................................1 Chapter I – Abundance, Excess, and Eikon Basilike ..................................................8 Chapter II – Debauchery and English Constitutions ................................................. 66 Chapter III – Rochester, “Rochester,” and more Rochester .................................... 116 Chapter IV – Satirists and Secret Historians .......................................................... 185 Conclusion -

Constitutional Reform and State Capacity Building: the Case of The

Constitutional reform and state capacity building: The case of the Glorious Revolution Elena Seghezza1 Abstract In the work we have tried try to explain why the delay in lowering the interest rate on English government debt after the Glorious Revolution is consistent with North and Weingast’s thesis. The transfer of political power from the Crown to Parliament was followed not only by an increase in tax revenue but also by substantial changes in its composition, namely a significant increase in the share of excise taxes relative to total revenue. Before the Glorious Revolution, Parliament was against the king having a predictable and reliable revenue, such as that raised by excise duty. The availability of this income would have allowed the king to count on continuous and abundant resources, freeing him from the need, in times of war, to convene Parliament to ask for authorization to increase taxes. Having a large amount of predictable and certain resources at his disposal, the king could maintain a standing army. By eliminating this risk the Glorious Revolution allowed the state to pursue the intensive growth of excise revenues. This policy choice was made by a coalition of interest groups represented in Parliament, namely the landowners and monied interests. These groups decided to set up a bureaucracy and increase the revenue from indirect taxes. By this decision the groups represented in Parliament shifted the tax burden of increasing public spending on to interest groups that had no political representation. Introduction This paper is a re-assessment of North and Weingast’s thesis according to which the ascent to the throne of England by William of Orange was accompanied by a reconfiguration of the distribution of political power 1 Elena Seghezza, Department of Economics, Genoa University, Italy. -

Locke, Lockean Ideas, and the Glorious Revolution Author(S): Lois G

Locke, Lockean Ideas, and the Glorious Revolution Author(s): Lois G. Schwoerer Source: Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Oct. - Dec., 1990), pp. 531-548 Published by: University of Pennsylvania Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2709645 Accessed: 16-05-2017 18:43 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2709645?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of Pennsylvania Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the History of Ideas This content downloaded from 128.111.121.42 on Tue, 16 May 2017 18:43:52 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Locke, Lockean Ideas, and the Glorious Revolution Lois G. Schwoerer The role and significance of John Locke's political ideas in English history and the part Locke played in English politics have been reinter- preted during the past twenty years or so. Thanks to the work of John Dunn, Peter Laslett, Martyn Thompson, -

Katharine Esdaile Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8x63sn4 No online items Katharine Esdaile Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by John Houlton, Marilyn Olsen, Catherine Wehrey, and Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © November 2016 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Katharine Esdaile Papers: Finding mssEsdaile 1 Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Katharine Esdaile Papers Dates (inclusive): 1845-1961 Bulk dates: 1900-1950 Collection Number: mssEsdaile Collector: Esdaile, Katharine Ada, 1881-1950 Extent: 101 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2203 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of English art historian Katharine Ada Esdaile (1881-1950). Much of the collection relates to her research of British monumental sculpture. Notably the collection includes more than 600 chiefly pre-World War II visitor booklets and pamphlets produced locally by British churches and approximately 3500 photographs taken or collected by Esdaile of sculpture, often funerary monuments in English churches. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher.