Deification in the Early Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845

Women, Slavery, and British Imperial Interventions in Mauritius, 1810–1845 Tyler Yank Department of History and Classical Studies Faculty of Arts McGill University, Montréal October 2019 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy © Tyler Yank 2019 ` Table of Contents ! Table of Contents .......................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Résumé ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................... 7 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 10 History & Historiography ............................................................................................................. 15 Definitions ..................................................................................................................................... 21 Scope of Study ............................................................................................................................. -

Oxford Book Fair List 2014

BERNARD QUARITCH LTD OXFORD BOOK FAIR LIST including NEW ACQUISITIONS ● APRIL 2014 Main Hall, Oxford Brookes University (Headington Hill Campus) Gipsy Lane, Oxford OX3 0BP Stand 87 Saturday 26th April 12 noon – 6pm - & - Sunday 27th April 10am – 4pm A MEMOIR OF JOHN ADAM, PRESENTED TO THE FORMER PRIME MINISTER LORD GRENVILLE BY WILLIAM ADAM 1. [ADAM, William (editor).] Description and Representation of the Mural Monument, Erected in the Cathedral of Calcutta, by General Subscription, to the Memory of John Adam, Designed and Executed by Richard Westmacott, R.A. [?Edinburgh, ?William Adam, circa 1830]. 4to (262 x 203mm), pp. [4 (blank ll.)], [1]-2 (‘Address of the British Inhabitants of Calcutta, to John Adam, on his Embarking for England in March 1825’), [2 (contents, verso blank)], [2 (blank l.)], [2 (title, verso blank)], [1]-2 (‘Description of the Monument’), [2 (‘Inscription on the Base of the Tomb’, verso blank)], [2 (‘Translation of Claudian’)], [1 (‘Extract of a Letter from … Reginald Heber … to … Charles Williams Wynn’)], [2 (‘Extract from a Sermon of Bishop Heber, Preached at Calcutta on Christmas Day, 1825’)], [1 (blank)]; mounted engraved plate on india by J. Horsburgh after Westmacott, retaining tissue guard; some light spotting, a little heavier on plate; contemporary straight-grained [?Scottish] black morocco [?for Adam for presentation], endpapers watermarked 1829, boards with broad borders of palmette and flower-and-thistle rolls, upper board lettered in blind ‘Monument to John Adam Erected at Calcutta 1827’, turn-ins roll-tooled in blind, mustard-yellow endpapers, all edges gilt; slightly rubbed and scuffed, otherwise very good; provenance: William Wyndham Grenville, Baron Grenville, 3 March 1830 (1759-1834, autograph presentation inscription from William Adam on preliminary blank and tipped-in autograph letter signed from Adam to Grenville, Edinburgh, 6 March 1830, 3pp on a bifolium, addressed on final page). -

Garofalo Book

Chapter 1 Introduction Fantasies of National Virility and William Wordsworth’s Poet Leader Violent Warriors and Benevolent Leaders: Masculinity in the Early Nineteenth-Century n 1822 British women committed a public act against propriety. They I commissioned a statue in honor of Lord Wellington, whose prowess was represented by Achilles, shield held aloft, nude in full muscular glory. Known as the “Ladies’ ‘Fancy Man,’” however, the statue shocked men on the statue committee who demanded a fig leaf to protect the public’s out- raged sensibilities.1 Linda Colley points to this comical moment in postwar British history as a sign of “the often blatantly sexual fantasies that gathered around warriors such as Nelson and Wellington.”2 However, the statue in its imitation of a classical aesthetic necessarily recalled not only the thrilling glory of Great Britain’s military might, but also the appeal of the defeated but still fascinating Napoleon. After all, the classical aesthetic was central to the public representation of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic regimes. If a classical statue was supposed to apotheosize Wellington, it also inevitably spoke to a revolutionary and mar- tial manhood associated with the recently defeated enemy. Napoleon him- self had commissioned a nude classical statue from Canova that Marie Busco speculates “would have been known” to Sir Richard Westmacott, who cast the bronze Achilles. In fact Canova’s Napoleon was conveniently located in the stairwell of Apsley House after Louis XVIII presented it to the Duke of Wellington.3 These associations with Napoleon might simply have underscored the British superiority the Wellington statue suggested. -

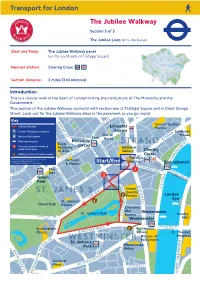

The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5

Transport for London. The Jubilee Walkway. Section 5 of 5. The Jubilee Loop (anti-clockwise). Start and finish: The Jubilee Walkway panel (on the south side of Trafalgar Square). Nearest station: Charing Cross . Section distance: 2 miles (3 kilometres). Introduction. This is a circular walk in the heart of London linking the institutions of The Monarchy and the Government. This section of the Jubilee Walkway connects with section one at Trafalgar Square and at Great George Street. Look out for the Jubilee Walkway discs in the pavement as you go round. Directions. This walk starts from Trafalgar Square. Did you know? Trafalgar Square was laid out in 1840 by Sir Charles Barry, architect of the new Houses of Parliament. The square, which is now a 'World Square', is a place for national rejoicing, celebrations and demonstrations. It is dominated by Nelson's Column with the 18-foot statue of Lord Nelson standing on top of the 171-foot column. It was erected in honour of his victory at Trafalgar. With Trafalgar Square behind you and keeping Canada House on the right, cross Cockspur Street and keep right. Go around the corner, passing the Ugandan High Commission to enter The Mall under the large stone Admiralty Arch - go through the right arch. Keep on the right-hand side of the broad avenue that is The Mall. Did you know? Admiralty Arch is the gateway between The Mall, which extends southwest, and Trafalgar Square to the northeast. The Mall was laid out as an avenue between 1660-1662 as part of Charles II's scheme for St James's Park. -

GIPE-002303-Contents.Pdf (2.817Mb)

HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRIOA.:" SINCE-~~;T;~~~;~r .-- G d IL - DhananJayarao a gl 1111111111111111111111111111111111 GIPE-PUNE-002: BY GEORGE MCCALL THEAL, LITT.D., "rLir' ... ,08&IQ. ..aIlB&R o. I'R. ROYAL .ACADBKY or am ••o • ., ~ ___B1i8!'01rDIN<! IIBIIBD o. '1'&. BOY.., .......M •• tMM:mnT, LONDON, BTC. t BT<J., ETC., PO •••RLV ~".P.B O' UB AILOBIV" O' TnB CA.PB COLORY, AND .£.'1: PRB81!1NT COLONIAL BI&'J'OBIOOaAPSBB WITH SIXTEEN MAPS AND CHARTS I~ FIVE VOLUMES VOL. II. THE CAPE COLONY FROM 1828 TO 1846, NATAL FROM 1824 TO 1845, AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE EMIGRANT FARMERS It'ROM 1836 TO 1847 LONDON SWA N SONNENSCHEIN & CO., LIM. 25 HIGH STREET, BLOOMSBlTRY 1908 _ All riyht. .........a HISTORY- - OF 'SOUTH AFRICA. The latest 'and most complet~ edition of this work consists of :---- History' and' Ethnography of A/rica south 0/ the Zambesi from the .settlement 0/ the Portuguese at So/ala in September I505 to' the conquest 0/ the Cape Colony by the BriHsh in September I795. In three volumes. Volume I contains a description of the Bushmen, H~tten tots, and Bantu, aI). account,o{the first voyages round the Cape ..¢:-GoocrHope of the Portuguese, the French, the English, and .- the Dutch, and a history of the Portuguese in South Africa in early times. Volumes II and III contain a history of the administration of the Dutch-East India Company'in South Africa, &c., &c. History 0/ South A/rica since' September I795. In five volumes. Volume I contains a history of the Cape Colony from 1795 to 1828 and an account of the Zulu wars of devastation and the formation of new Bantu communities. -

Copyright Statement

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2017 Dogs and Domesticity Reading the Dog in Victorian British Visual Culture Robson, Amy http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/10097 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. i ii Dogs and Domesticity Reading the Dog in Victorian British Visual Culture by Amy Robson A thesis submitted to Plymouth University in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD Art History, 2017 Humanities and Performing Arts 2017 iii Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisors, Dr James Gregory and Dr Jenny Graham, for their ongoing support throughout this project. I would also like to extend immeasurable thanks to Dr Gemma Blackshaw, who was involved in the early and later stages of my research project. Each of these individuals brought with them insights, character, and wit which helped make the PhD process all the more enjoyable. -

The Memory of Slavery in Liverpool in Public Discourse from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day

The Memory of Slavery in Liverpool in Public Discourse from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day Jessica Moody PhD University of York Department of History April 2014 Abstract This thesis maps the public, collective memory of slavery in Liverpool from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the present day. Using a discourse-analytic approach, the study draws on a wide range of ‘source genres’ to interrogate processes of collective memory across written histories, guidebooks, commemorative occasions and anniversaries, newspapers, internet forums, black history organisations and events, tours, museums, galleries and the built environment. By drawing on a range of material across a longue durée, the study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how this former ‘slaving capital of the world’ has remembered its exceptional involvement in transatlantic slavery across a two hundred year period. This thesis demonstrates how Liverpool’s memory of slavery has evolved through a chronological mapping (Chapter Two) which places memory in local, national and global context(s). The mapping of memory across source areas is reflected within the structure of the thesis, beginning with ‘Mapping the Discursive Terrain’ (Part One), which demonstrates the influence and intertextuality of identity narratives, anecdotes, metaphors and debates over time and genre; ‘Moments of Memory’ (Part Two), where public commemorative occasions, anniversaries and moments of ‘remembrance’ accentuate issues of ‘performing’ identity and the negotiation of a dissonant past; and ‘Sites of Memory’ (Part Three), where debate and discourse around particular places in Liverpool’s contested urban terrain have forged multiple lieux de memoire (sites of memory) through ‘myths’ of slave bodies and contestations over race and representation. -

Childish Ways: Anne Damer and Other Precursors to Childe Harold's

1 CHILDISH WAYS : ANNE DAMER AND OTHER PRECURSORS TO CHILDE HAROLD ’S PILGRIMAGE JONATHAN GROSS DE PAUL UNIVERSITY How did Anne Damer and William Beckford anticipate, and in a sense make possible, Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage ? A brief overview of these Byron precursors might be helpful. In 1787, William Beckford (author of Vathek) visited Lisbon as a social outcast after his reputed affair with William Courtenay in the Powderham scandal; he struggled unsuccessfully to be admitted to the King and Queen of Portugal and kept a journal recounting the events. Four years later, in 1791, Anne Damer arrived in the same city to recover her health. Her husband had committed suicide in 1776 and she lived a precarious life as an amateur actress, sculptress, and novelist. In fact, she wrote the rough draft of Belmour (1801) during her stay. In 1808, Byron had to consider whether he would be a politician (potentially a soldier), or a writer when he came to Lisbon. Though he had written several poems, they had received mixed reviews, and it was not clear whether Byron would ever mature successfully from the poetic persona he had established in Fugitive Pieces , Hours of Idleness , and English Bards and Scotch Reviewers . When he began the poem that made him famous in Cintra at the St. Lawrence hotel, Byron’s future was not firmly established. All three figures, Beckford, Damer, and Byron, viewed Portugal and Cintra, as places to recover their lost youth, and to celebrate the creative values associated with childishness which they explored in their art, whether in Vathek , Belmour , or Childe Harold . -

Annual Report 2017−2018

ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT REPORT COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL ROYAL 2017−2018 www.royalcollection.org.uk ANNUAL REPORT 2017−2018 ROYA L COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2018 www.royalcollection.org.uk AIMS OF THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST In fulfilling The Trust’s objectives, the Trustees’ aims are to ensure that: ~ the Royal Collection (being the works of art ~ the Royal Collection is presented and held by The Queen in right of the Crown interpreted so as to enhance public and held in trust for her successors and for the appreciation and understanding; nation) is subject to proper custodial control and that the works of art remain available ~ access to the Royal Collection is broadened to future generations; and increased (subject to capacity constraints) to ensure that as many people as possible are ~ the Royal Collection is maintained and able to view the Collection; conserved to the highest possible standards and that visitors can view the Collection ~ appropriate acquisitions are made when in the best possible condition; resources become available, to enhance the Collection and displays of exhibits ~ as much of the Royal Collection as possible for the public. can be seen by members of the public; When reviewing future plans, the Trustees ensure that these aims continue to be met and are in line with the Charity Commission’s general guidance on public benefit. This Report looks at the achievements of the previous 12 months and considers the success of each key activity and how it has helped enhance the benefit to the nation. -

Annual Report 2018−2019

ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT REPORT COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL ROYAL 2018−2019 www.rct.uk ANNUAL REPORT 2018−2019 ROYA L COLLECTION TRUST ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2019 www.rct.uk AIMS OF THE ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST CONTENTS In fulfilling The Trust’s objectives, the Trustees’ aims are to ensure that: ~ the Royal Collection (being the works of art ~ the Royal Collection is presented and CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 5 held by The Queen in right of the Crown interpreted so as to enhance public DIRECTOR’S INTRODUCTION 7 and held in trust for her successors and for the appreciation and understanding; nation) is subject to proper custodial control PRESENTATION AND PARTICIPATION 9 and that the works of art remain available ~ access to the Royal Collection is broadened Visiting the Palaces 9 to future generations; and increased (subject to capacity constraints) ~ Buckingham Palace 9 to ensure that as many people as possible are ~ The Royal Mews 11 ~ the Royal Collection is maintained and able to view the Collection; ~ Windsor Castle 12 conserved to the highest possible standards ~ Clarence House 12 and that visitors can view the Collection ~ appropriate acquisitions are made when ~ Palace of Holyroodhouse 16 in the best possible condition; resources become available, to enhance Exhibitions 21 the Collection and displays of exhibits Historic Royal Palaces & Loans 33 ~ as much of the Royal Collection as possible for the public. INTERPRETATION 37 can be seen by members of the public; Learning 37 Publishing 39 When reviewing future plans, the Trustees ensure that these aims continue to be met and are CARE OF THE COLLECTION 43 in line with the Charity Commission’s general guidance on public benefit. -

Introduction Enniskillen Papers

INTRODUCTION ENNISKILLEN PAPERS November 2007 Enniskillen Papers (D1702, D3689 and T2074) Table of Contents Summary .................................................................................................................3 Family estates..........................................................................................................4 The Wiltshire estate .................................................................................................5 The estates in 1883 .................................................................................................6 Family history...........................................................................................................9 Sir William Cole (1575?-1653) ...............................................................................10 'A brave, forward and prudent gentleman' .............................................................11 Sir John Cole, 1st Bt ..............................................................................................12 The Montagh estate...............................................................................................13 Sir Michael Cole.....................................................................................................14 The Florence Court conundrum .............................................................................15 Richard Castle's contribution in the 1730s?...........................................................16 The Ranelagh inheritance......................................................................................17