Copyright Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deification in the Early Century

chapter 1 Deification in the early century ‘Interesting, dignified, and impressive’1 Public monuments were scarce in Ireland at the begin- in 7 at the expense of Dublin Corporation, was ning of the nineteenth century and were largely con- carefully positioned on a high pedestal facing the seat fined to Dublin, which boasted several monumental of power in Dublin Castle, and in close proximity, but statues of English rulers, modelled in a weighty and with its back to the seat of learning in Trinity College. pompous late Baroque style. Cork had an equestrian A second equestrian statue, a portrait of George I by statue of George II, by John van Nost, the younger (fig. John van Nost, the elder (d.), was originally placed ), positioned originally on Tuckey’s Bridge and subse- on Essex Bridge (now Capel Street Bridge) in . It quently moved to the South Mall in .2 Somewhat was removed in , and was re-erected at the end of more unusually, Birr, in County Offaly, featured a sig- the century, in ,8 in the gardens of the Mansion nificant commemoration of Prince William Augustus, House, facing out over railings towards Dawson Street. Duke of Cumberland (–) (fig. ). Otherwise The pedestal carried the inscription: ‘Be it remembered known as the Butcher of Culloden,3 he was com- that, at the time when rebellion and disloyalty were the memorated by a portrait statue surmounting a Doric characteristics of the day, the loyal Corporation of the column, erected in Emmet Square (formerly Cumber- City of Dublin re-elevated this statue of the illustrious land Square) in .4 The statue was the work of House of Hanover’.9 A third equestrian statue, com- English sculptors Henry Cheere (–) and his memorating George II, executed by the younger John brother John (d.). -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) Had Only Seven Members but Influenced Many Other Artists

1 • Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 2 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

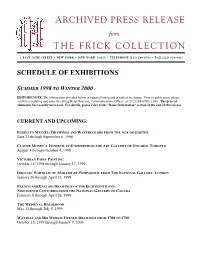

Archived Press Release the Frick Collection

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS SUMMER 1998 TO WINTER 2000 EDITORS NOTE: The information provided below is a partial listing and is subject to change. Prior to publication, please confirm scheduling and dates by calling Heidi Rosenau, Communications Officer, at (212) 288-0700, x 264. The price of admission has recently increased. For details, please refer to the “Basic Information” section at the end of this release. CURRENT AND UPCOMING: FUSELI TO MENZEL: DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLORS FROM THE AGE OF GOETHE June 23 through September 6, 1998 CLAUDE MONET’S VÉTHEUIL IN SUMMER FROM THE ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO, TORONTO August 4 through October 4, 1998 VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 DROUAIS’ PORTRAIT OF MADAME DE POMPADOUR FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON January 26 through April 25, 1999 FRENCH AND ENGLISH DRAWINGS OF THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA February 8 through April 26, 1999 THE MEDIEVAL HOUSEBOOK May 11 through July 5, 1999 WATTEAU AND HIS WORLD: FRENCH DRAWINGS FROM 1700 TO 1750 October 18, 1999 through January 9, 2000 UPCOMING: VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 Critically and commercially popular during the 19th century was the intriguing and distinctly British genre of Victorian fairy painting, the subject of an exhibition that comes this fall to The Frick Collection. The paintings and works on paper, roughly thirty in number, have been selected by Edgar Munhall, Curator of The Frick Collection, from a comprehensive touring exhibition – the first of its type for this subject. -

Lowell Libson Limited

LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 LOWELL LIBSON LIMITED BRITISH PAINTINGS WATERCOLOURS AND DRAWINGS 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · [email protected] www.lowell-libson.com LOWELL LI BSON LTD 2 0 1 0 Our 2010 catalogue includes a diverse group of works ranging from the fascinating and extremely rare drawings of mid seventeenth century London by the Dutch draughtsman Michel 3 Clifford Street · Londonw1s 2lf van Overbeek to the small and exquisitely executed painting of a young geisha by Menpes, an Australian, contained in the artist’s own version of a seventeenth century Dutch frame. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7734 8686 · Email: [email protected] Sandwiched between these two extremes of date and background, the filling comprises Website: www.lowell-libson.com · Fax: +44 (0)20 7734 9997 some quintessentially British works which serve to underline the often forgotten international- The gallery is open by appointment, Monday to Friday ism of ‘British’ art and patronage. Bellucci, born in the Veneto, studied in Dalmatia, and worked The entrance is in Old Burlington Street in Vienna and Düsseldorf before being tempted to England by the Duke of Chandos. Likewise, Boitard, French born and Parisian trained, settled in London where his fluency in the Rococo idiom as a designer and engraver extended to ceramics and enamels. Artists such as Boitard, in the closely knit artistic community of London, provided the grounding of Gainsborough’s early In 2010 Lowell Libson Ltd is exhibiting at: training through which he synthesised -

In South Kensington, C. 1850-1900

JEWELS OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM: GENDERED AESTHETICS IN SOUTH KENSINGTON, C. 1850-1900 PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK PH.D. HISTORY OF ART UCL 2 I, PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ______________________________________________ 3 ABSTRACT Several collections of brilliant objects were put on display following the opening of the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington in 1881. These objects resemble jewels both in their exquisite lustre and in their hybrid status between nature and culture, science and art. This thesis asks how these jewel-like hybrids – including shiny preserved beetles, iridescent taxidermised hummingbirds, translucent glass jellyfish as well as crystals and minerals themselves – functioned outside of normative gender expectations of Victorian museums and scientific culture. Such displays’ dazzling spectacles refract the linear expectations of earlier natural history taxonomies and confound the narrative of evolutionary habitat dioramas. As such, they challenge the hierarchies underlying both orders and their implications for gender, race and class. Objects on display are compared with relevant cultural phenomena including museum architecture, natural history illustration, literature, commercial display, decorative art and dress, and evaluated in light of issues such as transgressive animal sexualities, the performativity of objects, technologies of visualisation and contemporary aesthetic and evolutionary theory. Feminist theory in the history of science and new materialist philosophy by Donna Haraway, Elizabeth Grosz, Karen Barad and Rosi Braidotti inform analysis into how objects on display complicate nature/culture binaries in the museum of natural history. -

British Taste in the Nineteenth Century ••

BRITISH TASTE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY •• WILLIAM MULREADY The Sailing Match (S l) BRITISH TASTE IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY AUCKLAND CITY ART GALLERY • MAY 1962 Foreword This exhibition has been arranged for the 1962 Auckland Festival of Arts. We are particularlv grateful to all the owners of pictures who have been so generous with their loans. p. A. TOMORY Director Introduction This exhibition sets out to indicate the general taste of the nineteenth century in Britain. As only New Zealand collections have been used there are certain inevitable gaps, but the main aim, to choose paintings which would reflect both the public and private patronage of the time, has been reasonably accomplished. The period covered is from 1820 to 1880 and although each decade may not be represented it is possible to recognise the effect on the one hand of increasing middle class patronage and on the other the various attempts like the Pre-Raphaelite move ment to halt the decline to sentimental triviality. The period is virtually a history of the Royal Academy, which until 1824, when the National Gallery was opened, provided one of the few public exhibitions of paintings. Its influence, therefore, even late in the century, on the public taste was considerable, and artistic success could onlv be assured by the Academy. It was, however, the rise of the middle class which dictated, more and more as the century progressed, the type of art produced by the artists. Middle class connoisseur- ship was directed almost entirely towards contemporary painting from which it de manded no more than anecdote, moral, sentimental or humorous, and landscapes or seascapes which proclaimed ' forever England.' Ruskin, somewhat apologetically (On the Present State of Modern Art 1867), detected two major characteristics — Compassionateness — which he observed had the tendency of '. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

Animal Painters of England from the Year 1650

JOHN A. SEAVERNS TUFTS UNIVERSITY l-IBRAHIES_^ 3 9090 6'l4 534 073 n i«4 Webster Family Librany of Veterinary/ Medicine Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine at Tuits University 200 Westboro Road ^^ Nortli Grafton, MA 01536 [ t ANIMAL PAINTERS C. Hancock. Piu.xt. r.n^raied on Wood by F. Bablm^e. DEER-STALKING ; ANIMAL PAINTERS OF ENGLAND From the Year 1650. A brief history of their lives and works Illustratid with thirty -one specimens of their paintings^ and portraits chiefly from wood engravings by F. Babbage COMPILED BV SIR WALTER GILBEY, BART. Vol. II. 10116011 VINTOX & CO. 9, NEW BRIDGE STREET, LUDGATE CIRCUS, E.C. I goo Limiiei' CONTENTS. ILLUSTRATIONS. HANCOCK, CHARLES. Deer-Stalking ... ... ... ... ... lo HENDERSON, CHARLES COOPER. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... i8 HERRING, J. F. Elis ... 26 Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 32 HOWITT, SAMUEL. The Chase ... ... ... ... ... 38 Taking Wild Horses on the Plains of Moldavia ... ... ... ... ... 42 LANDSEER, SIR EDWIN, R.A. "Toho! " 54 Brutus 70 MARSHALL, BENJAMIN. Portrait of the Artist 94 POLLARD, JAMES. Fly Fishing REINAGLE, PHILIP, R.A. Portrait of Colonel Thornton ... ... ii6 Breaking Cover 120 SARTORIUS, JOHN. Looby at full Stretch 124 SARTORIUS, FRANCIS. Mr. Bishop's Celebrated Trotting Mare ... 128 V i i i. Illustrations PACE SARTORIUS, JOHN F. Coursing at Hatfield Park ... 144 SCOTT, JOHN. Portrait of the Artist ... ... ... 152 Death of the Dove ... ... ... ... 160 SEYMOUR, JAMES. Brushing into Cover ... 168 Sketch for Hunting Picture ... ... 176 STOTHARD, THOMAS, R.A. Portrait of the Artist 190 STUBBS, GEORGE, R.A. Portrait of the Duke of Portland, Welbeck Abbey 200 TILLEMAN, PETER. View of a Horse Match over the Long Course, Newmarket .. -

William Holman Hunt's Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 William Holman Hunt’s Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk Jennie Mae Runnels Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4920 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. William Holman Hunt’s Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History at Virginia Commonwealth University. Jennie Runnels Virginia Commonwealth University Department of Art History MA Thesis Spring 2017 Director: Catherine Roach Assistant Professor Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia April 2017 Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1 Holman Hunt and Henry Monk: A Chance Meeting Chapter 2 Jan van Eyck: Rediscovery and Celebrity Chapter 3 Signs, Symbols and Text Conclusion List of Images Selected Bibliography Acknowledgements In writing this thesis I have benefitted from numerous individuals who have been generous with their time and encouragement. I owe a particular debt to Dr. Catherine Roach who was the thesis director for this project and truly a guiding force. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Eric Garberson and Dr. Kathleen Chapman who served on the panel as readers and provided valuable criticism, and Dr. Carolyn Phinizy for her insight and patience. -

Three Centuries of British Art

Three Centuries of British Art Three Centuries of British Art Friday 30th September – Saturday 22nd October 2011 Shepherd & Derom Galleries in association with Nicholas Bagshawe Fine Art, London Campbell Wilson, Aberdeenshire, Scotland Moore-Gwyn Fine Art, London EIGHTEENTH CENTURY cat. 1 Francis Wheatley, ra (1747–1801) Going Milking Oil on Canvas; 14 × 12 inches Francis Wheatley was born in Covent Garden in London in 1747. His artistic training took place first at Shipley’s drawing classes and then at the newly formed Royal Academy Schools. He was a gifted draughtsman and won a number of prizes as a young man from the Society of Artists. His early work consists mainly of portraits and conversation pieces. These recall the work of Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) and Benjamin Wilson (1721–1788), under whom he is thought to have studied. John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–1779), his friend and occasional collaborator, was also a considerable influence on him in his early years. Despite some success at the outset, Wheatley’s fortunes began to suffer due to an excessively extravagant life-style and in 1779 he travelled to Ireland, mainly to escape his creditors. There he survived by painting portraits and local scenes for patrons and by 1784 was back in England. On his return his painting changed direction and he began to produce a type of painting best described as sentimental genre, whose guiding influence was the work of the French artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805). Wheatley’s new work in this style began to attract considerable notice and in the 1790’s he embarked upon his famous series of The Cries of London – scenes of street vendors selling their wares in the capital. -

3. Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

• Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 1 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works.