William Holman Hunt's Portrait of Henry Wentworth Monk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement

Andrea Korda “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) Citation: Andrea Korda, “‘The Streets as Art Galleries’: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring12/korda-on-the-streets-as-art-galleries-hubert- herkomer-william-powell-frith-and-the-artistic-advertisement. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Korda: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 1 (Spring 2012) “The Streets as Art Galleries”: Hubert Herkomer, William Powell Frith, and the Artistic Advertisement by Andrea Korda By the second half of the nineteenth century, advertising posters that plastered the streets of London were denounced as one of the evils of modern life. In the article “The Horrors of Street Advertisements,” one writer lamented that “no one can avoid it.… It defaces the streets, and in time must debase the natural sense of colour, and destroy the natural pleasure in design.” For this observer, advertising was “grandiose in its ugliness,” and the advertiser’s only concern was with “bigness, bigness, bigness,” “crudity of colour” and “offensiveness of attitude.”[1] Another commentator added to this criticism with more specific complaints, describing the deficiencies in color, drawing, composition, and the subjects of advertisements in turn. Using adjectives such as garish, hideous, reckless, execrable and horrible, he concluded that advertisers did not aim to appeal to the intellect, but only aimed to attract the public’s attention. -

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER and STUDIES Volume 27, Number 2 Autumn, 1993

EVELYN WAUGH NEWSLETTER AND STUDIES Volume 27, Number 2 Autumn, 1993 THE AWAKENING CONSCIENCE IN BRIDESHEAD REVISITED By Elaine E. Whitaker (University of Alabama at Birmingham) Crucial to understanding the emotions which underlie Julia Flyte's renunciation of Charles Ryder in Brideshead Revisited is "Ruskin's description" of "a picture of Holman Hunt's cal.led 'The Awakened Conscience'" (290). Julia, who has not seen the picture, concludes from Ryder's reading of Ruskin, "You're perfectly right. That's exactly what I did feel" (290). That these feelings were aroused by her brother Bridey's statement that Julia was "living in sin" (285, 287) has never been in dispute. However, both the title of Hunt's painting and the location of Ruskin's criticism require further explication. Although Waugh, his editors, and his critics have consistently referred to The Awakened Conscience, the title Holman Hunt assigned to this work was not The Awakened Conscience but rather The Awakening Conscience. Waugh's apparent error links Hunt's painting to its Victorian predecessors, The A wakened Conscience by Richard Redgrave and The Awakened Conscience by Thomas Brooks.' Because Waugh was not a casual observer of these Victorian painters, he should not have been prone to such an error. On the contrary, Waugh indicates his interest not only by the allusion in Brides head but also by his prior claim that "The A wakened Conscience ... is, perhaps, the noblest painting by any Englishman."' Thus, Waugh's alteration of Hunt's title deserves investigation. The painting which Waugh praises but mistitles depicts a young woman who has risen from her lover's lap, though her lover continues to hold her with one arm and to touch the keys of a piano with his free hand. -

以『前拉菲爾派』為例 Representation of Shakespeare’S Women in Pre-Raphaelite Art

國立臺灣師範大學國際與社會科學學院歐洲文化與觀光研究所 碩士論文 Graduate Institute of European Cultures and Tourism College of International Studies and Social Sciences National Taiwan Normal University Master Thesis 莎士比亞女角的再現 - 以『前拉菲爾派』為例 Representation of Shakespeare’s Women in Pre-Raphaelite Art 許艾薇 Ivy Tang 指導教授﹕陳學毅 博士 Dr. Hsueh-I CHEN 中華民國 107 年 06 月 June 2018 Acknowledgement This thesis could not have been written without the assistance of and support from numerous individuals. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Hsueh-I Chen for his generous encouragement, consistent guidance, and full support for the completion of this project. I am hugely appreciative to Professor Chen for encouraging me when I faced doubts and questioned myself throughout the process. I am grateful for the guidance and assistance that Professor Dinu Luca provided in the early stages of this thesis. I am fortunate for his close attention and assistance throughout the shaping of this thesis. My appreciation also goes to my thesis committee members Professor Louis Lo and Professor Candida Syndikus, for their careful examination of my thesis. Their comments and advice helped me to consider new interdisciplinary approaches in the study. I thank Professor Lo for the guidance since undergraduate for whom had first introduced me to the study of Ophelia’s madness and representations. Professor Syndikus’s careful reading and probing questioning added depth and coherence to my thesis. This thesis has benefited from the above individual’s vast knowledge of literature, Shakespeare, British art, philosophical theories, Victorian studies, sensitive editing, insightful interpretations of paintings, and sensitive editing. Without the help of them, this thesis would not have been able to be completed. -

The Afterglow in Egypt Teachers' Notes

Teacher guidance notes The Afterglow in Egypt 1861 A zoomable image of this painting is available by William Holman Hunt on our website to use in the classroom on an interactive whiteboard or projector oil on canvas 82 x 37cm www.ashmolean.org/learning-resources These guidance notes are designed to help you use paintings from our collection as a focus for cross- curricular teaching and learning. A visit to the Ashmolean Museum to see the painting offers your class the perfect ‘learning outside the classroom’ opportunity. Starting questions Questions like these may be useful as a starting point for developing speaking and listening skills with your class. What catches your eye first? What is the lady carrying? Can you describe what she is wearing? What animals can you see? Where do you think the lady is going? What do you think the man doing? Which country do you think this could be? What time of day do you think it is? Why do you think that? If you could step into the painting what would would you feel/smell/hear...? Background Information Ideas for creative planning across the KS1 & 2 curriculum The painting You can use this painting as the starting point for developing pupils critical and creative thinking as well as their Hunt painted two verions of ‘The Afterglow in Egypt’. The first is a life-size painting of a woman learning across the curriculum. You may want to consider possible ‘lines of enquiry’ as a first step in your cross- carrying a sheaf of wheat on her head, which hangs in Southampton Art Gallery. -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

Art Et Littérature À L'époque Victorienne. Home Sweet Home Or

HOME, SWEET HOME OR BLEAK HOUSE ? Art et littérature à l'époque Victorienne Dans la même série, les Annales Littéraires de l'Université de Besançon ont publié en 1977, sous le numéro 198 : THE ARTIST'S PROGRESS Art, littérature et société en Grande-Bretagne Sommaire : PELTRAULT Claude, L'Enfer ou l'architecture de l'illusion. HAMARD Marie-Claire, L'enfant dans l'art anglais du XVIe au XVIIe siècle. CARRÉ Jacques, Alexander Pope et l'architecture. FERRER Daniel, A The Rake 's Progress, Hogarth-Stravinsky. LEHMANN Gilly, L'art de la table en Angleterre au XVIIIe siècle. TATU Chantal, Présence, fonction et signification des arts dans Les Mystères d'Udolphe d'Anne Radcliffe. MARTIN Jean-Paul, Comment Constable peint la peinture. ROSSITER Andrew, La critique d'art de William Thackeray : un aperçu sur la Royal Academy aux alentours de 1840. Cet ouvrage de 161 pages, illustré de 11 planches, est distribué par Les Belles Lettres, 95, Boulevard Raspail, Paris VIe, au prix de 120 FF. Les Annales ont aussi publié en 1982, sous le numéro 267 : LIFT NOT THE PAINTED VEIL... Recherches sur la peinture anglaise et américaine. Sommaire : CARRÉ Jacques, Un aristocrate et son image les portraits de Lord Burlington. BRUCKMULLER-GENLOT Danielle, Un intransigeant victorien : William Holman Hunt, ou la voie étroite du préraphaélitisme. LEHMANN Patrick-André, «Hughes vs Hughes» ou le premier illustra- teur de Tom Brown 's Schooldays. HAMARD Marie-Claire, Les premières années du New English Art Club. HAMARD Marie -Claire, Les illustrateurs du Yellow Book. MARTIN Jean-Pierre, Ce que peint Francis Bacon (tentative de description). -

St Barnabas and St Paul, with St Thomas the Martyr Parish Profile

September 2018 St Barnabas and St Paul, with St Thomas the Martyr Parish profile Unity and Mutual Respect United, friendly and welcoming – we hope that is the impression our congregation might Why I worship here: make on a first-time visitor to our principal service, the 10.30am Sunday High Mass at St Traditional liturgy with Barnabas. Ours is not a predominantly elderly congregation: we have young families as well its timeless beauty and as people who have worshipped here for many decades, and everything in between. holiness. Originally worshippers came predominantly from the parish itself, then an industrial suburb; now they come from all over Oxford and beyond – indeed, all over the world – drawn by our Tractarian heritage, with its beautiful liturgy, excellent music, and sound but concise sermons. The congregation also reflects Oxford’s place in the wider world; many nationalities and backgrounds are represented, pointing to the profound truth that we are one Contents: in Christ. Unity and Mutual Respect Our New Incumbent History Liturgy and Worship Music Church Life Parish Links About the Parish Vicarage Properties Challenges and Opportunities From the Bishop The Oxford Deanery This fellowship is also expressed socially. The newly-installed kitchen/servery at the west Appendices: end of the church not only encourages a lively coffee-time after Mass but enables us to Summary Accounts 2017 gather for Lent courses and study days over a shared lunch and to celebrate feast days in some style. Motion & Statement of Need Map of Parish Throughout this profile the reader will find occasional statements headed ‘Why I worship here’. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) Had Only Seven Members but Influenced Many Other Artists

1 • Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 2 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013

Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM Last updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 Updated Wednesday, February 13, 2013 | 2:36:43 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Art and Design, 1848-1900 February 17, 2013 - May 19, 2013 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required (*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. Ford Madox Brown The Seeds and Fruits of English Poetry, 1845-1853 oil on canvas 36 x 46 cm (14 3/16 x 18 1/8 in.) framed: 50 x 62.5 x 6.5 cm (19 11/16 x 24 5/8 x 2 9/16 in.) The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Presented by Mrs. W.F.R. Weldon, 1920 William Holman Hunt The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, 1854-1860 oil on canvas 85.7 x 141 cm (33 3/4 x 55 1/2 in.) framed: 148 x 208 x 12 cm (58 1/4 x 81 7/8 x 4 3/4 in.) Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Presented by Sir John T. -

Archived Press Release the Frick Collection

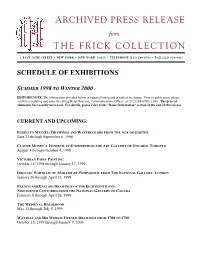

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 SCHEDULE OF EXHIBITIONS SUMMER 1998 TO WINTER 2000 EDITORS NOTE: The information provided below is a partial listing and is subject to change. Prior to publication, please confirm scheduling and dates by calling Heidi Rosenau, Communications Officer, at (212) 288-0700, x 264. The price of admission has recently increased. For details, please refer to the “Basic Information” section at the end of this release. CURRENT AND UPCOMING: FUSELI TO MENZEL: DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLORS FROM THE AGE OF GOETHE June 23 through September 6, 1998 CLAUDE MONET’S VÉTHEUIL IN SUMMER FROM THE ART GALLERY OF ONTARIO, TORONTO August 4 through October 4, 1998 VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 DROUAIS’ PORTRAIT OF MADAME DE POMPADOUR FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON January 26 through April 25, 1999 FRENCH AND ENGLISH DRAWINGS OF THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES FROM THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF CANADA February 8 through April 26, 1999 THE MEDIEVAL HOUSEBOOK May 11 through July 5, 1999 WATTEAU AND HIS WORLD: FRENCH DRAWINGS FROM 1700 TO 1750 October 18, 1999 through January 9, 2000 UPCOMING: VICTORIAN FAIRY PAINTING October 14, 1998 through January 17, 1999 Critically and commercially popular during the 19th century was the intriguing and distinctly British genre of Victorian fairy painting, the subject of an exhibition that comes this fall to The Frick Collection. The paintings and works on paper, roughly thirty in number, have been selected by Edgar Munhall, Curator of The Frick Collection, from a comprehensive touring exhibition – the first of its type for this subject. -

Art in the Modern World

Art in the Modern World A U G U S T I N E C O L L E G E Beata Beatrix 1863 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI The Girlhood of Mary 1849 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Ecce ancilla Domini 1850 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Our English Coasts William Holman HUNT | 1852 Our English Coasts detail 1852 William Holman HUNT The Hireling Shepherd 1851 | William Holman HUNT The Awakening Conscience 1853 William Holman HUNT The Scapegoat 1854 | William Holman HUNT The Shadow of Death 1870-73 William Holman HUNT Christ in the House of His Parents 1849 | John Everett MILLAIS Portrait of John Ruskin 1854 John Everett MILLAIS Ophelia 1852 | John Everett MILLAIS George Herbert at Bemerton 1851 | William DYCE The Man of Sorrows 1860 | William DYCE Louis XIV & Molière 1862 | Jean-Léon GÉRÔME Harvester 1875 William BOUGUEREAU Solitude 1890 Frederick Lord LEIGHTON Seaside 1878 James Jacques Joseph TISSOT The Awakening Heart 1892 William BOUGUEREAU The Beguiling of Merlin 1874 | Edward BURNE JONES Innocence 1873 William BOUGUEREAU Bacchante 1894 William BOUGUEREAU The Baleful Head 1885 Edward BURNE JONES Springtime 1873 Pierre-Auguste COT The Princesse de Broglie James Joseph Jacques TISSOT A Woman of Ambition 1883-85 James Joseph Jacques TISSOT Prayer in Cairo Jean-Léon GEROME The Boyhood of Raleigh 1870 | John Everett MILLAIS Flaming June 1895 Frederick Lord LEIGHTON Lady Lilith 1864 Dante Gabriel ROSSETTI Holyday 1876 | James Joseph Jacques TISSOT Autumn on the Thames 1871 James Joseph Jacques TISSOT A Dream of the Past: Sir Isumbras at the Ford 1857 | John Everett MILLAIS A Reading