The Bureau of Navigation, 1862-1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

Women Ashore: the Contribution of WAVES to US Naval Science and Technology in World War II

Women Ashore: The Contribution of WAVES to US Naval Science and Technology in World War II Kathleen Broome Williams On 30 July 1947, US Navy (USN) women celebrated their fifth anniversary as WAVES: Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Se rv ice. In ceremonies across the count ry, flags snapped and crisp young women saluted. Congratulatory messages arrived from navy brass around the globe. The Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the Atlantic Fleet, Admiral William H.P. Blandy, noted (perhaps too optimistically) that "the splendid serv ices rendered by the WAVES...and their uncomplaining spirit of sacrifice and devotion to duty at all times" would never be forgotten by "a grateful navy."' Admiral Louis E. Denfeld, C-in-C Pacific, wrote more perceptively that "the vital role" played by the WAVES "in the defeat of the Axis nations is known to all and, though often unsung in peacetime, their importance has not decreased." Significantly, Admiral Denfeld added that he would welcome the addition of the WAVES "to the Regular Naval Establishment," an issue then hanging in the balance.' Indeed, for all the anniversary praise, the WAVES' contribution to wartime successes did not even guarantee them a permanent place in the navy once peace returned nor, until recently, has their "vital role" in the Allied victory received much scholarly attention. This article helps to round out the historical record by briefly surveying one aspect of the role of the WAVES: their contribution to naval science and technology. The navy has always been a technical service but World War II was the first truly technological war. -

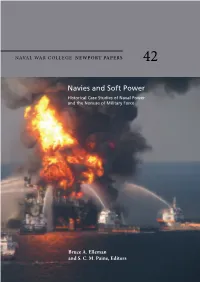

Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 42 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 42 Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil-rig fire—fighting the blaze and searching for survivors. U.S. Coast Guard photograph, available at “USGS Multimedia Gallery,” USGS: Science for a Changing World, gallery.usgs.gov/. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its au thenticity. ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4 (e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1) is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superinten- dent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Navies and Soft Power: Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force, edited by Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, as an official publica tion of the College. It is prohibited to use NWC’s logo on any republication of this book without the express, written permission of the Editor, Naval War College Press, or the editor’s designee. For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-00001 ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4; e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1 Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force Bruce A. -

The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF THE ATOMIC BOMB: A SUBMERGED CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF THE SUNKEN FLEET OF OPERATION CROSSROADS AT BIKINI AND KWAJALEIN ATOLL LAGOONS REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS Prepared for: The Kili/Bikini/Ejit Local Government Council By: James P. Delgado Daniel J. Lenihan (Principal Investigator) Larry E. Murphy Illustrations by: Larry V. Nordby Jerry L. Livingston Submerged Cultural Resources Unit National Maritime Initiative United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers Number 37 Santa Fe, New Mexico 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS ... LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ......................................... 111 FOREWORD ................................................... vii Secretary of the Interior. Manuel Lujan. Jr . ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................... ix CHAPTER ONE: Introduction ........................................ 1 Daniel J. Lenihan Project Mandate and Background .................................. 1 Methodology ............................................... 4 Activities ................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: Operation Crossroads .................................. 11 James P. Delgado The Concept of a Naval Test Evolves ............................... 14 Preparing for the Tests ........................................ 18 The AbleTest .............................................. 23 The Baker Test ............................................. 27 Decontamination Efforts ....................................... -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

Hydrography, the Marine Environment, and the Culture of Nautical Charts in the United States Navy, 1838-1903

CONTROLLING THE GREAT COMMON: HYDROGRAPHY, THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT, AND THE CULTURE OF NAUTICAL CHARTS IN THE UNITED STATES NAVY, 1838-1903 A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Jason W. Smith August 2012 Examining Committee Members: Gregory J.W. Urwin, Temple University Beth Bailey, Temple University Andrew C. Isenberg, Temple University John B. Hattendorf, United States Naval War College i © Copyright 2012 by Jason W. Smith All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT This dissertation uses hydrography as a lens to examine the way the United States Navy has understood, used, and defined the sea during the nineteenth century. It argues, broadly, that naval officers and the charts and texts they produced framed the sea as a commercial space for much of the nineteenth century, proceeding from a scientific ethos that held that the sea could be known, ordered, represented, and that it obeyed certain natural laws and rules. This proved a powerful alternative to existing maritime understandings, in which mariners combined navigational science with folkloric ideas about how the sea worked. Hydrography was an important aspect of the American maritime commercial predominance in the decades before the Civil War. By the end of the century, however, new strategic ideas, technologies, and the imperatives of empire caused naval officers and hydrographers to think about the sea in new ways. After the Spanish-American War of 1898, the Navy pursued hydrography with increased urgency, faced with defending the waters of a vast new oceanic empire. Surveys, charts, and the language of hydrography became central to the Navy’s war planning and war gaming, to the strategic debate over where to establish naval bases, and, ultimately, it figured significantly in determining the geography of the American empire. -

An Interview with CAPT Tom Anderson, USN, Littoral Combat Ship Program Manger, PEO Littoral Combat Ships Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret)

SURFACE SITREP Page 1 P PPPPPPPPP PPPPPPPPPPP PP PPP PPPPPPP PPPP PPPPPPPPPP Volume XXXIII, Number 2 July 2017 An Interview with CAPT Tom Anderson, USN, Littoral Combat Ship Program Manger, PEO Littoral Combat Ships Conducted by CAPT Edward Lundquist, USN (Ret) What can you tell us about the testing and evaluation being We had already conducted the IOT&E for the Freedom (monohull) conducted for the littoral combat ship (LCS) seaframes? variant awhile back in USS Fort Worth (LCS 3). So both variants In 2016, we completed Initial Operational Test and Evaluation have achieved Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and both have (IOT&E) in the Independence-variant, with multiple associated now deployed. tests, including at-sea firing of SEARAM, which is the ship’s Anti- Ship Cruise Missile system. It was successful, scoring a direct hit In 2016, we also conducted live-fire testing in the form of shock on BQM target drones. We also conducted swarm raids by surface trials in both variants aboard USS Milwaukee (LCS 5) and USS fast attack craft. One of the strengths of LCS, with its focused- Jackson (LCS 6). mission Surface Warfare (SUW) mission package embarked, is its So both variants have been through their ability to counter swarm raids. With initial operational testing. the 57mm and the 30 mm guns, we Yes. We had already conducted the IOT&E went out and conducted successful for the Freedom variant awhile back in LCS 3 operations against swarm raids, (in 2013). Now both variants have completed scoring mission kill hits on multiple IOT&E, achieved IOC, and both have now high speed maneuverable seaborne deployed. -

Bureau of Naval Weapons Stored at the Washington National Records

. LEAVE BLANK REQUEST FOR RECORDS •DISPOSITION AUTHORITY JOB •NO. (See Instructions on reverse) N1-402-89-1 TO: GENERAL SERVICES ADMINISTRATION DATE REC//;~/9/ NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE, WASHINGTON, DC 20408 -- 1. FROM (Agency or establishment) NOTIFICATION TO AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY In accordance with the provisions of 44 U.S.C 3303a 2. MAJOR SUBDIVISION the disposal request. including amendments. is approved except for items that may be marked "disposition not BUREAU OF NAVAL WEAPONS approved" or "withdrawn" in column 10. If no records 3. MINOR SUBDIVISION are proposed for disposal. the Signature of the Archivist is not required. \,. - 4. NAME OF PERSON WITH WHOM TO CONFER 5. TELEPHONE EXT. ARCHIVIST OF THE UNITEO STATES R.W. MACKAY (202)501-6048 D~;11( ~ -::::::--.,~ 6. CERTIFICATE OF AGENCY REPRESENTATIVE I hereby certify that I am authorized to act for this agency in matters pertaining to the disposal of the agency's records; that the records proposed for disposal in this Request of 64 page(s) are not now needed for the business of this agency or will not be needed after the retention periods specified; and that written concurrence from the General Accounting Office, if required under the provisions of Title 8 of the GAO Manual for Guidance of Federal Agencies, is attached. A. GAO concurrence: D is attached; or ~ is unnecessary. B. DATE - D. TITLE C. ~TU~E 0 GE~ESENTATIVE ~ ~.~~ E.W. ALLER, CAPT, ~SN DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY RECORDS MANAGER 9. GRS OR 10. ACTION 7. 8. DESCRIPTION OF ITEM SUPERSEDED TAKEN ITEM (With Inclusive Dates or Retention Periods) JOB (NARSUSE NO. -

The Sensory Environments of Civil War Prisons

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2015 The eS nsory Environments of Civil War Prisons Evan A. Kutzler University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Kutzler, E. A.(2015). The Sensory Environments of Civil War Prisons. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3572 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SENSORY ENVIRONMENTS OF CIVIL WAR PRISONS by Evan A. Kutzler Bachelor of Arts Centre College, 2010 Master of Arts University of South Carolina, 2012 _____________________________________________ Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Mark M. Smith, Major Professor Don Doyle, Committee Member Lacy K. Ford, Committee Member Stephen Berry, Committee Member Lacy K. Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Evan A. Kutzler, 2015 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Neither the sound of bells, nor the smell of privies, nor the feeling of lice factored into my imagined dissertation when I matriculated at the University of South Carolina in 2010. The Civil War, however, had always loomed large. As a child, my mother often took me metal detecting in the woods, fields, and streams of middle Tennessee in what became our shared hobby. An early lesson in sensory history occurred one summer in a cow pasture (with owner’s permission) along the Nashville and Decatur Railroad. -

Ships of the United States Navy and Their Sponsors 1797-1913

Ships of the United States Navy and Their Sponsors I I J 2 9 3— 9 3 MA t 1 OD*sC&~y.1 <;V, 1 *- . I<f-L$ (~<r*J 7/. / 2_ COPYRIGHT, 1925 BY THE SOCIETY OF SPONSORS OF THE UNITED STATES NAVY • « • « « • t « » * . « » • : •: • • • • c , THE-PEfMPTON-PKES'a ' NORWOOD • MASS. D-8> A • • ••• • ••• • *:•• : . ft>. • • • • • . ••• . > .• ••• FOREWORD HIS volume is supplementary to "Ships of the United States Navy and their Sponsors, 1797-1913," published in 1913 to bring together from widely separated and in- accessible sources all obtainable facts relating to the launch- ing and naming of the fighting craft of our Navy, old and new, and the bestowal of the names upon these vessels by sponsors. Records of Navy launchings and namings had been preserved nowhere in book form up to that time. La- borious research in many directions was necessary to col- lect and verify fragmentary data. The present volume has been prepared primarily for the Society of Sponsors of the United States Navy, and also in response to requests for an up-to-date book, from non- members and from libraries. Full accounts of all launchings would be repetition. Typical accounts only are given. Complete biographies of individuals, or complete histo- ries of vessels are manifestly impossible in this volume. Historical notes are not given as complete histories. Bi- ographical notes of patriots for whom Navy vessels have been named are not given as complete biographies. Con- spicuous facts of biographies and of histories are set forth for the purpose of interesting and unmistakable identifi- cation and for the inspiration of every reader with patriotic pride in the achievements of our Navy. -

Missouri's Hidden Civil

MISSOURI’S HIDDEN CIVIL WAR: FINANCIAL CONSPSIRACY AND THE DECLINE OF THE PLANTER ELITE, 1861-1865 _________________________________________ A dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________________ In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________________ by MARK W. GEIGER Dr. LeeAnn Whites, Supervisor May 2006 © Copyright by Mark W. Geiger 2006 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition to the persons listed below who provided helpful criticism and comments in the preparation of this manuscript, I also wish to acknowledge the financial support of the Richard S. Brownlee Fund, William Woods University, the Frank F. and Louis I. Stephens Dissertation Fellowship Fund, the Allen Cook White Jr. Fellowship Fund, and the Business History Conference which enabled me to do the research on which this dissertation is based. Audiences at the Missouri Conference on History, the State Historical Society of Missouri, the Business History Conference, the Southern History Association, and the American Historical Association all provided important feedback. Prof. LeeAnn Whites Prof. Susan Flader Prof. Theodore Koditschek Prof. Ronald Ratti Prof. Robert Weems, Jr. Prof. Lisa Ruddick Prof. Michael Fellman Prof. Mark Neely, Jr. Prof. Christopher Phillips Prof. Amy Dru Stanley Prof. Amy Murrell Taylor Prof. Christopher Waldrep ii Dr. Gary Kremer Prof. Laurel Wilson Robert Dyer Mary Carraway Margie Gurwit Mrs. Mary Holmes Ara Kaye Jack Kennedy T. J. Stiles iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii List of Illustrations vii Maps, Tables, and Charts ix Abstract xi Introduction 1 Historiographical Overview Chapter Summaries Section I: Financial Conspiracy 1. Missouri Banks in the Secession Crisis 27 2. -

The Capital Ship Program in the United States Navy, 1934

THE CAPITAL SHIP PROGRAM IN THE UNITED STATES NAVY, 1934-1945 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Malcolm Muir, Jr. ***** The Ohio State University 1976 Reading Committee: Approved By Professor Allan R. Millett Professor Harry L. Coles Adviser Professor Marvin R. Zahniser Department of History ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In reviewing the course of this project, it is sur prising to realize how many people have had a hand in it. The genesis of the paper can be traced to my father who gave me, along with so much else, an abiding interest in maritime matters and especially in the great ships. More immediately I owe much of the basic outline of this paper to my advisor. Professor Allan R. Millett of the Depart ment of History, The Ohio State University, who kept the project in focus through prompt and thorough editing. I would like to thank Professors Harry L. Coles and Marvin Zahniser for reading the manuscript. In gathering materials, I received aid from a great number of people, particularly the staffs of the Naval His torical Center, the National Archives (including both the main and the Suitland branches), the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, the Naval War College Archives, and The Ohio State Univ ersity Library. I especially appreciated the kindness of such people as Ms. Mae C. Seaton of the Naval Historical Center, Dr. Gibson B. Smith of the National Archives, and Dr. Anthony Nicolosi of the Naval War College.