PNAAH514.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Línea Base De Conocimientos Sobre Los Recursos Hidrológicos E Hidrobiológicos En El Sistema TDPS Con Enfoque En La Cuenca Del Lago Titicaca ©Roberthofstede

Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca ©RobertHofstede Oficina Regional para América del Sur La designación de entidades geográficas y la presentación del material en esta publicación no implican la expresión de ninguna opinión por parte de la UICN respecto a la condición jurídica de ningún país, territorio o área, o de sus autoridades, o referente a la delimitación de sus fronteras y límites. Los puntos de vista que se expresan en esta publicación no reflejan necesariamente los de la UICN. Publicado por: UICN, Quito, Ecuador IRD Institut de Recherche pour Le Développement. Derechos reservados: © 2014 Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza y de los Recursos Naturales. Se autoriza la reproducción de esta publicación con fines educativos y otros fines no comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de parte de quien detenta los derechos de autor con tal de que se mencione la fuente. Se prohíbe reproducir esta publicación para venderla o para otros fines comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de quien detenta los derechos de autor. Con el auspicio de: Con la colaboración de: UMSA – Universidad UMSS – Universidad Mayor de San André Mayor de San Simón, La Paz, Bolivia Cochabamba, Bolivia Citación: M. Pouilly; X. Lazzaro; D. Point; M. Aguirre (2014). Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca. IRD - UICN, Quito, Ecuador. 320 pp. Revisión: Philippe Vauchel (IRD), Bernard Francou (IRD), Jorge Molina (UMSA), François Marie Gibon (IRD). Editores: UICN–Mario Aguirre; IRD–Marc Pouilly, Xavier Lazzaro & DavidPoint Portada: Robert Hosfstede Impresión: Talleres Gráficos PÉREZ , [email protected] Depósito Legal: nº 4‐1-196-14PO, La Paz, Bolivia ISBN: nº978‐99974-41-84-3 Disponible en: www.uicn.org/sur Recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos del sistema TDPS Prólogo Trabajando por el Lago Más… El lago Titicaca es único en el mundo. -

Cuadro De Tarifas En El Departamento De Oruro

Gobierno Autónomo Departamental de Oruro Oruro - Bolivia CUADRO DE TARIFAS EN EL DEPARTAMENTO DE ORURO PROVINCIA SABAYA ORIGEN DESTINO MODALIDAD PASAJE REFERENCIAL EN Bs. PASAJE SIST. TARIFARIO EN Bs. ORURO SABAYA OMNIBUS 30 29,75 ORURO SABAYA MINIBUS 35 34,17 ORURO PISIGA OMNIBUS 35 33,36 ORURO PISIGA MINIBUS 40 37,24 ORURO COIPASA OMNIBUS 35 33,92 ORURO COIPASA MINIBUS 40 37,11 ORURO CHIPAYA OMNIBUS 30 28,89 ORURO CHIPAYA MINIBUS 35 34,43 PROVINCIA MEJILLONES ORIGEN DESTINO MODALIDAD PASAJE REFERENCIAL EN Bs. PASAJE SIST. TARIFARIO EN Bs. ORURO HUACHACALLA OMNIBUS 20 19,37 ORURO HUACHACALLA MINIBUS 25 24,39 ORURO TODOS SANTOS OMNIBUS 35 33,21 ORURO TODOS SANTOS MINIBUS 40 37,11 PROVINCIA CERCADO ORIGEN DESTINO MODALIDAD PASAJE REFERENCIAL EN Bs. PASAJE SIST. TARIFARIO EN Bs. ORURO CARACOLLO MINIVAN 5 4,69 ORURO LA JOYA MINIBUS 7 5,57 ORURO (VINTO) HUAYÑAPASTO TAXIVAGONETA 4 4,13 ORURO SORACACHI (OBRAJES)MINIVAN 6 5,99 ORURO SORACACHI (PARIA) MINIBUS 5 4,05 ORURO SORACACHI (SORACACHI)MINIBUS 5 4,61 ORURO SORACACHI (CAYHUASI)MINIBUS 6 6,25 ORURO SORACACHI (LEQUEPALCA)MINIBUS 10 9,1 ORURO EL CHORO OMNIBUS 10 9,02 ORURO EL CHORO MINIBUS 10 9,71 PROVINCIA TOMAS BARRON ORIGEN DESTINO MODALIDAD PASAJE REFERENCIAL EN Bs. PASAJE SIST. TARIFARIO EN Bs. ORURO EUCALIPTUS MINIVAN 10 9,88 PROVINCIA PANTALEON DALENCE ORIGEN DESTINO MODALIDAD PASAJE REFERENCIAL EN Bs. PASAJE SIST. TARIFARIO EN Bs. ORURO HUANUNI MINIBUS 5 5,16 ORURO HUANUNI OMNIBUS 5 4,92 ORURO MACHAMARCA MINIBUS 3,5 3,35 Plaza 10 de Febrero, Presidente Montes, Bolívar y Adolfo Mier www.oruro.gob.bo Gobierno Autónomo Departamental de Oruro Oruro - Bolivia PROVINCIA POOPO ORIGEN DESTINO MODALIDAD PASAJE REFERENCIAL EN Bs. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 14490-BO STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT BOLIVIA Public Disclosure Authorized RURAL WATER AND SANITATION PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized DECEMBER 15, 1995 Public Disclosure Authorized Country Department III Environment and Urban Development Division Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Office Currency Equivalents Currency unit = Boliviano US$1 = 4.74 Bolivianos (March 31, 1995) All figures in U.S. dollars unless otherwise noted Weights and Measures Metric Fiscal Year January 1 - December 31 Abbreviations and Acronyms DINASBA National Directorate of Water and Sanitation IDB International Development Bank NFRD National Fund for Regional Development NSUA National Secretariat for Urban Affairs OPEC Fund Fund of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries PROSABAR Project Management Unit within DINASBA UNASBA Departmental Water and Sanitation Unit SIF Social Investment Fund PPL Popular Participation Law UNDP United Nations Development Programme Bolivia Rural Water and Sanitation Project Staff Appraisal Report Credit and Project Summary .................................. iii I. Background .................................. I A. Socioeconomic setting .................................. 1 B. Legal and institutional framework .................................. 1 C. Rural water and sanitation ............................. , , , , , , . 3 D. Lessons learned ............................. 4 II. The Project ............................. 5 A. Objective ............................ -

LISTASORURO.Pdf

LISTA DE CANDIDATAS Y CANDIDATOS PRESENTADOS POR LAS ORGANIZACIONES POLITICAS ANTE EL TRIBUNAL ELECTORAL DEPARTAMENTAL DE ORURO EN FECHA: 28 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2020 sigla PROVINCIA MUNICIPIO NOMBRE CANDIDATURA TITULARIDAD POSICION NOMBRES PRIMER APELLIDO SEGUNDO APELLIDO APU Carangas CORQUE Alcaldesa(e) Titular 1 FELIX MAMANI FERNANDEZ APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Titular 1 RUTH MARINA CHOQUE CARRIZO APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Suplente 1 RENE TAPIA BENAVIDES APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Titular 2 JOEL EDIBERTO CHOQUE CHURA APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Suplente 2 REYNA GOMEZ NINA APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Titular 3 LILIAN MORALES GUTIERREZ APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Suplente 3 IVER TORREZ CONDE APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Titular 4 ROMER CARRIZO BENAVIDES APU Carangas CORQUE Concejalas(es) Suplente 4 FLORINDA COLQUE MUÑOZ BST Cercado Oruro Gobernadora (or) Titular 1 EDDGAR SANCHEZ AGUIRRE BST Cercado Oruro Asambleista Departamental por Territorio Titular 1 EDZON BLADIMIR CHOQUE LAZARO BST Cercado Oruro Asambleista Departamental por Territorio Suplente 1 HELEN OLIVIA GUTIERREZ BST Carangas Corque Asambleista Departamental por Territorio Titular 1 ANDREA CHOQUE TUPA BST Carangas Corque Asambleista Departamental por Territorio Suplente 1 REYNALDO HUARACHI HUANCA BST Abaroa Challapata Asambleista Departamental por Territorio Titular 1 GUIDO MANUEL ENCINAS ACHA BST Abaroa Challapata Asambleista Departamental por Territorio Suplente 1 JAEL GABRIELA COPACALLE ACHA BST Poopó Poopó Asambleista Departamental -

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of Hist

Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 ABSTRACT Conscript Nation: Negotiating Authority and Belonging in the Bolivian Barracks, 1900-1950 by Elizabeth Shesko Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ John D. French, Supervisor ___________________________ Jocelyn H. Olcott ___________________________ Peter Sigal ___________________________ Orin Starn ___________________________ Dirk Bönker An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Elizabeth Shesko 2012 Abstract This dissertation examines the trajectory of military conscription in Bolivia from Liberals’ imposition of this obligation after coming to power in 1899 to the eve of revolution in 1952. Conscription is an ideal fulcrum for understanding the changing balance between state and society because it was central to their relationship during this period. The lens of military service thus alters our understandings of methods of rule, practices of authority, and ideas about citizenship in and belonging to the Bolivian nation. In eliminating the possibility of purchasing replacements and exemptions for tribute-paying Indians, Liberals brought into the barracks both literate men who were formal citizens and the non-citizens who made up the vast majority of the population. -

Oatao.Univ-Toulouse.Fr/ Eprints ID: 5602

Open Archive Toulouse Archive Ouverte (OATAO) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author-deposited version published in: http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/ Eprints ID: 5602 To cite this version: Salvarredy-Aranguren, Matias Miguel and Probst, Anne and Roulet, Marc Evidencias sedimentarias y geoquimicas de la pequeño edad de hielo en el lago milluni grande del altiplano boliviano. (2009) Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina, vol. 65 (n°4). pp. 660-673. ISSN 1851-8249 Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to the repository administrator: [email protected] EVIDENCIAS SEDIMENTARIAS Y GEOQUIMICAS DE LA PEQUEÑA EDAD DE HIELO EN EL LAGO MILLUNI GRANDE DEL ALTIPLANO BOLIVIANO Matías Miguel SALVARREDY-ARANGUREN a,b,1* ¤ , Anne PROBST c,d y Marc ROULET a,e,† a Laboratoire des Mécanismes et Transferts en Géologie (LMTG), Toulouse, Francia. Email: [email protected] b Instituto de Geología y Recursos Minerales, Servicio Geológico Minero Argentino, Buenos Aires. c Université de Toulouse , UPS, INP , EcoLab (Laboratoire d'écologie fonctionnelle), Castanet-Tolosan, France d CNRS , EcoLab, Castanet-Tolosan, France, Email:[email protected] e Institut de Recherche pour le Développement, HYBAM, La Paz, Bolivia† † fallecido en 2006 RESUMEN El lago de Milluni Grande (LMG) está ubicado en el flanco occidental de los Andes Orientales en el valle de Milluni que po- see una clásica forma en U dado que se encuentra en una región glacial. El lago es el más grande de este valle, y dado que se halla situado al cierre de cuenca, resulta estratégico para albergar un registro sedimentario de los últimos 450 años. -

Ayllus Y Comunidades De Ex Hacienda

Tierra y territorio: thaki en los ayllus y comunidades de ex hacienda INVESTIGACIONES REGIONALES I Tierra y territorio: thaki en los ayllus y comunidades de ex hacienda Eliseo Quispe López Alberto Luis Aguilar Calle Ruth Carol Rocha Grimoldi Norka Araníbar Cossío Blanca Huanacu Bustos Walter Condori Uño Dirección de Postgrado Centro de Ecología Programa de Investigación e Investigación Científica y Pueblos Andinos Estratégica en Bolivia de la Universidad Técnica de Oruro La Paz, 2002 III Esta publicación cuenta con el auspicio del Directorio General para la Cooperación Internacional del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de los Países Bajos (DGIS). Quispe López, Eliseo Tierra y territorio : thaki en los ayllus y comunidades de ex hacienda / Eliseo Quispe López; Alberto Luis Aguilar Calle; Ruth Carol Rocha Grimoldi; Norka Aranibar Cossio; Blanca Huanacu Bustos; Walter Condori Uño. — La Paz : FUNDACIÓN PIEB, Julio 2002. xiv.; 220 p. , tbls. ; 21 cm. — (Investigaciones Regionales ; no. 4) D.L. : 4-1-978-02 ISBN: 99905-817-9-7 : Encuadernado SOCIOLOGÍA RURAL / PARCELACIÓN DE LA TIERRA / PROPIEDAD DE LA TIERRA / TIERRAS COMUNALES / IDENTIDAD CULTURAL / REFORMA DE TENENCIA DE LA TIERRA / ORURO 1. título 2. serie D.R. © FUNDACION PIEB, julio 2002 Edificio Fortaleza, Piso 6, Of. 601 Av. Arce Nº 2799, esquina calle Cordero, La Paz Teléfonos: 243 25 82 - 243 52 35 Fax: 243 18 66 Correo electrónico: [email protected] website: www.pieb.org Casilla postal: 12668 Diseño gráfico de cubierta: Alejandro Salazar Edición: entrelíneas.COMUNICACION EDITORIAL Wilmer Urrelo Producción: Editorial Offset Boliviana Ltda. Calle Abdón Saavedra 2101 Tels.: 241-0448 • 241-2282 • 241-5437 Fax: 242-3024 – La Paz - Bolivia Impreso en Bolivia Printed in Bolivia IV Índice Presentación ...................................................................................................................... -

20150331191630 0.Pdf

2 3 Esta publicación cuenta con el auspicio del Fondo Climático de Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Alemania y de la Embajada de la República Federal de Alemania en Bolivia. Glaciares Bolivia Testigos del 12 cambio climático Concepto, textos y edición general: Teresa Torres-Heuchel Edición gráfica:Gabriela Fajardo E. Diseño de portada y diagramación: Erik Rodríguez Archivo gráfico y documentación: Heidi Stache, Ekkehard Jordan, Deutscher Alpenverein (DAV), Instituto Boliviano de la Montaña (BMI) Fotografía de portada: Dirk Hoffmann Colaboradoras: Alicia de Mier, Johanna Hömberg El contenido de la presente publicación es de responsabilidad del Instituto Boliviano de la Montaña (BMI) Urbanización La Barqueta, Achumani Calle 28 B esquina calle 4 C Sajama 5 Teléfono: 2.71.24.32. Correo electrónico: [email protected] Casilla: 3-12417 La Paz, Bolivia Depósito Legal: 4–1–2654–14 Impreso por CREATIVA 2 488 588 (La Paz) 4 5 Vista de Mina Pacuni, Quimsa Cruz (BMI / 2014) 6 Glaciares Bolivia Testigos del 12 cambio climático Indice Prólogo Presentación 12 Glaciares I. Sajama II. San Enrique III. Illimani IV. Picacho Kasiri V. Wila Manquilisani VI. Chacaltaya VII. Chiar Kerini VIII. Zongo IX. Lengua Quebrada X. Maria Lloco XI. Wila Llojeta XII. Culin Thojo La vida en torno al glaciar Glaciares y el ciclo hídrico Bofedales, tesoros de montaña Lagunas glaciares y los nuevos riesgos para la población de montaña El cambio climático en Bolivia Bolivia y los bolivianos en el cambio climático Buscando limitar el calentamiento global a 2º C COP 20 en puertas, glaciares andinos expuestos a ojos del mundo 7 8 Región Nigruni, Cordillera Oriental (BMI / 2014) Prólogo Frenar el calentamiento global y desarrollar soluciones para la adaptación al cambio climático es una tarea global. -

The Cordillera Real

44 THE CORDILLERA REAL THE CORDILLERA REAL , BY EVELIO ECHEVARRIA C. HE lovely ranges of Southern Peru slope gradually down to the shores of Lake Titicaca, but this is not their end; to the east of Carabaya knot springs another ridge, which enters Bolivia and reaches its maximum elevation and magnificence in the Cordillera Real of the latter country. The name Cordillera Real was given by the Spaniards as homage to a range of royal dignity; it is located in the north-west of Bolivia, between I5° 40" and 16° 40" S., running roughly north-west to south east for an approximate length of 100 miles. This range was termed by Austrian mountaineers ' der Himalaya der N euen Welt'. Although this honour may now be disputed by several Peruvian cordilleras, it contains nevertheless mountain scenery of Himalayan grandeur; six twenty-thousanders and scores of lesser peaks are found in the region between Illampu (20,873 ft.) and Illimani (21 ,201 ft.), the mighty pillars of each extreme. The Cordillera Real is a snow and ice range; it forms a lovely back ground for that remarkable high plateau, the Bolivian Altiplano, and is in full sight nine months a year. The white peaks, the steppe-like plain and the empty, blue skies have given to this part of Bolivia a Tibetan air that many travellers have noticed; and the Mongolian features of the Aymara Indians, stolidly facing the chill winds, reinforce this opinion. General description In the north and in the south the Cordillera Real rises over deep mountain basins ; peaks like Illimani soar well above the wooded hills of Coroico and Inquisive, towns only 4,700 ft. -

Condoriri Laguna Chiar Khota Cumbre Huayna Potosí

Condoriri Laguna Chiar Khota Cumbre Huayna Potosí Pocas ciudades provocan sensaciones tan extraordinarias como La Paz. Rodeada por la Cordillera de Los Andes y teniendo al Illimani como su montaña tutelar, encierra atractivos naturales tan imponentes y contrastantes como el Valle de la Luna, el Valle de Zongo, con sus siete diferentes pisos ecológicos y las lagunas de Pampalarama, al pie del nevado Wilamankilisani en las que nace, cristalino, el rio Choqueyapu. Esta Guía de Montañas ofrece al turista de aventura, la posibilidad de admirar el paisaje maravilloso de la Cordillera de los Andes y enfrentar, si desea, el desafío de escalar sus picos más altos, una prueba en que el hombre se propone vencer los obstáculos de la naturaleza, quizás con el secreto afán de encontrar sus propios límites y posibilidades. La guía invita a propios y visitantes a recorrer los espectaculares paseos que ofrece la Cordillera, para la práctica del trekking, escalada en roca, alpinismo, camping, safari fotográfico, desde donde se aprecia la naturaleza multifacética y de grandes retos. Bienvenidos sean todos a conocer o a redescubrir la magia que surge del espléndido entorno natural que circunda a la ciudad de La Paz. Luis Revilla Herrero Alcalde de La Paz HUAYNA POTOSÍ 05 LAGUNA MAMANCOTA 06 TREKKING COHONI BASE CAMP 20 GLACIAR VIEJO 06 TREKKING UNNI - PINAYA - COHONI - TAHUAPALCA (PEQUEÑO ILLIMANI) 1 2 CHARQUINI 06 TREKKING COHONI - LAMBATE (GRAN ILLIMANI) 21 LAKE MAMANCOTA 07 TREKKING PINAYA - COHONI - TAHUAPALCA (SMALL ILLIMANI) 22 THE OLD GLACIER 07 TREKKING -

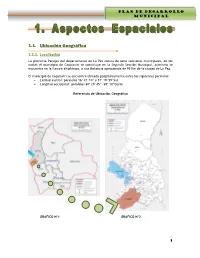

1.1. Ubicación Geográfica

PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI 1.1. Ubicación Geográfica 1.1.1. Localización La provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz consta de ocho secciones municipales, de los cuales el municipio de Caquiaviri se constituye en la Segunda Sección Municipal, asimismo se encuentra en la llanura altiplánica, a una distancia aproximada de 95 Km de la ciudad de La Paz. El municipio de Caquiaviri se encuentra ubicado geográficamente entre los siguientes paralelos: Latitud austral: paralelos 16º 47´10” y 17º 19´59”Sur Longitud occidental: paralelos 68º 29´45”- 69º 10”Oeste Referencia de Ubicación Geográfica GRAFICO Nº1 GRAFICO Nº2 1 PLAN DE DESARROLLO MUNICIPAL G.M. CAQUIAVIRI Ubicación del Municipio Caquiaviri en la Provincia Pacajes GRAFICO Nº3 1.1.2. Límites Territoriales El municipio de Caquiaviri tiene la siguiente delimitación: Límite Norte; Municipios de Jesús de Machaca y San Andrés de Machaca de la provincia Ingavi y el Municipio Nazacara de Pacajes que es la Séptima Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Sur; Municipios Coro Coro, Calacoto y Charaña que son Primera, Tercera y Quinta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Este; Municipio Comanche que es Cuarta Sección de la provincia Pacajes del departamento de La Paz. Límite Oeste; Municipio de Santiago de Machaca de la provincia José Manuel Pando del departamento de La Paz. 1.1.3. Extensión La Provincia Pacajes posee una extensión total de 10.584 km², de la cual la Segunda Sección Municipal Caquiaviri representa el 14 % del total de la provincia, lo que equivale a una superficie de 1.478 Km². -

Caryophyllaceae)

4 LUNDELLIA DECEMBER, 2017 NOMENCLATURAL NOTES ON THE ANDEAN GENERA PYCNOPHYLLOPSIS AND PYCNOPHYLLUM (CARYOPHYLLACEAE) Martın´ E. Timana´ Departamento de Humanidades, Seccion´ Geografıa,´ and Centro de Investigacion´ en Geografıa´ Aplicada (CIGA) Pontificia Universidad Catolica´ del Peru,´ Av. Universitaria 1801, San Miguel, Lima 32. Peru´ Email: [email protected] Abstract: The nomenclature of the high Andean genera Pycnophyllopsis Skottsb. and Pycnophyllum J. Remy´ is examined. Eight species of Pycnophyllopsis are recognized; lectotypes or neotypes are selected when required; a new species, Pycnophyllopsis smithii is proposed and two new combinations are made. The genus Plettkea Mattf. is reduced to a synonym of Pycnophyllopsis. Ten species of Pycnophyllum are accepted, including a new species, Pycnophyllum huascaranum and lectotypes or neotypes are selected when needed. Resumen: Se examina la nomenclatura de los generos´ altoandinos Pycnophyllopsis Skottsb. y Pycnophyllum J. Remy.´ Se reconocen ocho especies de Pycnophyllopsis; se designan lectotipos y neotipos cuando es requerido; se propone una nueva especie, Pycnophyllopsis smithii, y dos nuevas combinaciones. Se aceptan diez especies de Pycnophyllum, incluyendo una nueva especie, Pycnophyllum huascaranum; se designan lectotipos y neotipos cuando es requerido. Keywords: Caryophyllaceae, Alsinoideae, Pycnophyllopsis, Pycnophyllum, Plettkea, Andes, nomenclature, Peru, Bolivia. The Caryophyllaceae consists of 100 Andes and the mountain regions of North genera and almost 3000 species (Herna´ndez and Central America. Some genera (includ- et al., 2015). Traditionally, the family has ing several endemics) of the Caryophyllaceae been divided into three subfamilies (Alsi- reach the southern hemisphere, particularly noideae Fenzl, Caryophylloideae Arnott , the high Andes and the south temperate and and Paronychioideae Meisner, but see Har- sub-Antarctic regions.