The Cordillera Real

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACTIVIDAD SÍSMICA EN EL ENTORNO DE LA FALLA PACOLLO Y VOLCANES PURUPURUNI – CASIRI (2020 - 2021) (Distrito De Tarata – Región Tacna)

ACTIVIDAD SÍSMICA EN EL ENTORNO DE LA FALLA PACOLLO Y VOLCANES PURUPURUNI – CASIRI (2020 - 2021) (Distrito de Tarata – Región Tacna) Informe Técnico N°010-2021/IGP CIENCIAS DE LA TIERRA SÓLIDA Lima – Perú Mayo, 2021 Instituto Geofísico del Perú Presidente Ejecutivo: Hernando Tavera Director Científico: Edmundo Norabuena Informe Técnico Actividad sísmica en el entorno de la falla Pacollo y volcanes Purupuruni - Casiri (2020 – 2021). Distrito de Tarata – Región Tacna Autores Yanet Antayhua Lizbeth Velarde Katherine Vargas Hernando Tavera Juan Carlos Villegas Este informe ha sido producido por el Instituto Geofísico del Perú Calle Badajoz 169 Mayorazgo Teléfono: 51-1-3172300 Actividad sísmica en el entorno de la falla Pacollo y volcanes Purupuruni – Casiri (2020 – 2021) ACTIVIDAD SÍSMICA EN EL ENTORNO DE LA FALLA PACOLLO Y VOLCANES PURUPURUNI - CASIRI (2020 – 2021) Distrito de Tarata – Región Tacna Lima – Perú Mayo, 2021 2 Instituto Geofísico del Perú Actividad sísmica en el entorno de la falla Pacollo y volcanes Purupuruni – Casiri (2020 – 2021) RESUMEN Este estudio analiza las características sismotectónicas de la actividad sísmica ocurrida en el entorno de la falla Pacollo y volcanes Purupuruni- Casiri (distrito de Tarata – región Tacna), durante el periodo julio de 2020 a mayo de 2021. Desde mayo de 2020 hasta mayo de 2021, en el área de estudio se ha producido dos periodos de crisis sísmica separados por otro en donde la ocurrencia de sismos era constante, pero con menor frecuencia. El primer periodo de crisis sísmica ocurrió en el periodo del 15 al 30 de julio del 2020 con la ocurrencia de 3 eventos sísmicos que alcanzaron magnitud de M4.2. -

Races of Maize in Bolivia

RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E. David H. Timothy Efraín DÍaz B. U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Edgar Anderson William L. Brown NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Publication 747 Funds were provided for publication by a contract between the National Academythis of Sciences -National Research Council and The Institute of Inter-American Affairs of the International Cooperation Administration. The grant was made the of the Committee on Preservation of Indigenousfor Strainswork of Maize, under the Agricultural Board, a part of the Division of Biology and Agriculture of the National Academy of Sciences - National Research Council. RACES OF MAIZE IN BOLIVIA Ricardo Ramírez E., David H. Timothy, Efraín Díaz B., and U. J. Grant in collaboration with G. Edward Nicholson Calle, Edgar Anderson, and William L. Brown Publication 747 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL Washington, D. C. 1960 COMMITTEE ON PRESERVATION OF INDIGENOUS STRAINS OF MAIZE OF THE AGRICULTURAL BOARD DIVISIONOF BIOLOGYAND AGRICULTURE NATIONALACADEMY OF SCIENCES- NATIONALRESEARCH COUNCIL Ralph E. Cleland, Chairman J. Allen Clark, Executive Secretary Edgar Anderson Claud L. Horn Paul C. Mangelsdorf William L. Brown Merle T. Jenkins G. H. Stringfield C. O. Erlanson George F. Sprague Other publications in this series: RACES OF MAIZE IN CUBA William H. Hatheway NAS -NRC Publication 453 I957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN COLOMBIA M. Roberts, U. J. Grant, Ricardo Ramírez E., L. W. H. Hatheway, and D. L. Smith in collaboration with Paul C. Mangelsdorf NAS-NRC Publication 510 1957 Price $1.50 RACES OF MAIZE IN CENTRAL AMERICA E. -

Línea Base De Conocimientos Sobre Los Recursos Hidrológicos E Hidrobiológicos En El Sistema TDPS Con Enfoque En La Cuenca Del Lago Titicaca ©Roberthofstede

Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca ©RobertHofstede Oficina Regional para América del Sur La designación de entidades geográficas y la presentación del material en esta publicación no implican la expresión de ninguna opinión por parte de la UICN respecto a la condición jurídica de ningún país, territorio o área, o de sus autoridades, o referente a la delimitación de sus fronteras y límites. Los puntos de vista que se expresan en esta publicación no reflejan necesariamente los de la UICN. Publicado por: UICN, Quito, Ecuador IRD Institut de Recherche pour Le Développement. Derechos reservados: © 2014 Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza y de los Recursos Naturales. Se autoriza la reproducción de esta publicación con fines educativos y otros fines no comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de parte de quien detenta los derechos de autor con tal de que se mencione la fuente. Se prohíbe reproducir esta publicación para venderla o para otros fines comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de quien detenta los derechos de autor. Con el auspicio de: Con la colaboración de: UMSA – Universidad UMSS – Universidad Mayor de San André Mayor de San Simón, La Paz, Bolivia Cochabamba, Bolivia Citación: M. Pouilly; X. Lazzaro; D. Point; M. Aguirre (2014). Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca. IRD - UICN, Quito, Ecuador. 320 pp. Revisión: Philippe Vauchel (IRD), Bernard Francou (IRD), Jorge Molina (UMSA), François Marie Gibon (IRD). Editores: UICN–Mario Aguirre; IRD–Marc Pouilly, Xavier Lazzaro & DavidPoint Portada: Robert Hosfstede Impresión: Talleres Gráficos PÉREZ , [email protected] Depósito Legal: nº 4‐1-196-14PO, La Paz, Bolivia ISBN: nº978‐99974-41-84-3 Disponible en: www.uicn.org/sur Recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos del sistema TDPS Prólogo Trabajando por el Lago Más… El lago Titicaca es único en el mundo. -

Suma Qamaña Y Desarrollo El T'hinkhu Necesario

Suma Qamaña y Desarrollo El t'hinkhu necesario PPPooorrr MMMaaarrriiiooo TTTooorrrrrreeezzz EEEggguuuiiinnnooo Mario Torrez Eguino Suma Qamaña y Desarrollo El t'hinkhu necesario Edición al cuidado de Javier Medina y Simón Yampara Programa Nacional Biocultura Indice Presentación ................................... ..............................................................................9 Prólogo ................................................................................................................11 I. Urakpacha 1. Estructura y proceso de desarrollo del Qamaña. Espacio de bienestar. ...........................................................................15 2. Pacha y ecología ....................................................................................35 3. Ecología aymara: unidad e interacción de fuerzas-energías materiales-espirituales y territoriales para la qamaña, con Simón Yampara ............................41 ® Mario Torrez Eguino 4. Características rememorativas de la ecología D.L.: andina en el Qullasuyu ........................................................................55 5. Ecosistemas ...........................................................................................65 Primera Edición: Marzo 2012 II. Uñjaña Cuidados de edición: Freddy Ramos A. Foto tapa: Archivo CADA 6. El conocimiento hierático en el saber andino, con Simón Yampara .............................................................................75 Diseño de cubierta, diagramación e impresión: 7. Lógica del pensamiento andino -

ILLIMANI and the NAZIS. E. S. G. De La Motte

ILLIMANI AND THE NAZIS ILLIMANI AND THE NAZIS BY E. S. G. DE LA MOTTE E traveller to Bolivia from Buenos Aires spends three and a half weary days in the train with no interesting scenery to relieve the monotony of his existence. He leaves the dead flat Argentine pampas, where the horizon is like the horizon at sea, and passes almost imperceptibly to the equally flat, but much more barren, high tableland of Bolivia situated at 12,ooo ft. above sea-level. There is a difference, however. This tableland runs as a relatively narrow belt for hundreds of miles between the two main Andine ranges, and therefore has the advantage over the dreary expanses of Argentina that mountains of some sort are visible from most parts of it. Nevertheless, it is with relief that towards the end of the journey the immense ice-draped mass of Illimani is seen close at hand. The height of Illimani is still uncertain, as no triangulation has yet been made of it. All those who have climbed it, however, have. taken aneroid readings and these give results varying between 20,700 ft. ·and 22,400 ft. The probability is that the lower limit is nearer the truth, so 21 ,ooo ft. may reasonably be taken as a fair approximation. In any case, whatever the exact height may be, the mountain is a singularly striking one on account of its isolation, its massive form, and its position of domination over La Paz, which is the seat of the Bolivian Government, and from many of whose houses and streets the three heavily iced summits can be seen. -

De L1 a L2: ¿Primero El Castellano Y Después El Aimara? ENSEÑANZA DEL AIMARA COMO SEGUNDA LENGUA EN OPOQUERI (CARANGAS, ORURO)

UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN SIMÓN FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN DEPARTAMENTO DE POST GRADO PROGRAMA DE EDUCACIÓN INTERCULTURAL BILINGÜE PARA LOS PAÍSES ANDINOS PROEIB Andes De L1 a L2: ¿Primero el castellano y después el aimara? ENSEÑANZA DEL AIMARA COMO SEGUNDA LENGUA EN OPOQUERI (CARANGAS, ORURO) Román Mamani Rodríguez Tesis presentada a la Universidad Mayor de San Simón, en cumplimiento parcial de los requisitos para la obtención del título de Magíster en Educación Intercultural Bilingüe con la mención Planificación y Gestión Asesor de tesis: Dr. Gustavo Gottret Requena Cochabamba, Bolivia 2007 La presente tesis “De L1 a L2: ¿Primero el castellano y después el aimara? ENSEÑANZA DEL AIMARA COMO SEGUNDA LENGUA EN OPOQUERI (CARANGAS, ORURO) fue aprobada el ............................................ Asesor Tribunal Tribunal Tribunal Jefe del Departamento de Post-Grado Decano Dedicatoria A las abuelas y abuelos comunarios del ayllu. A los vivientes de nuestro ancestral idioma aimara. A las madres y padres de familia pobladores de Opoqueri. A los dueños usuarios de nuestra milenaria lengua originaria. A las tías y tíos difusores del aimara en diferentes comunidades. A las hermanas y hermanos portadores del aimara en diversas ciudades. A las sobrinas y sobrinos receptores de la herencia cultural y lingüística aimara. A las compañeras y compañeros residentes de Opoqueri en Buenos Aires (Argentina). A las profesoras y profesores facilitadores de nuestro idioma aimara en el Awya Yala. Román Mamani Rodríguez, 2007. Jiwasanakataki Ayllu kumunankiri awicha awichunakaru. Pachpa aymara arusana wiñaya jakiri ajayuparu. Jupuqiri markachirinakana mama tata wilamasinakataki. Pachpa arusana wiñaya qamañasana apnaqawi katxarutapa. Taqituqi kumunanakana aymara qhananchiri tiyanaka tiyunakasataki. -

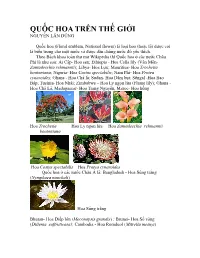

Quốc Hoa Trên Thế Giới

QUỐ C HOA TRÊN THẾ GIỚ I NGUYỄN LÂN DŨNG Quốc hoa (Floral emblem, National flower) là loại hoa (hoăc̣ lá) đươc̣ coi là biểu trưng cho một nước và được dân chúng nước đó yêu thích. Theo Bách khoa toàn thư mở Wikipedia thì Quốc hoa ở các nước Châu Phi là như sau: Ai Câp̣ - Hoa sen; Ethiopia - Hoa Calla lily (Vân Môn- Zantadeschia rehmannii); Libya- Hoa Lưụ ; Mauritius- Hoa Trochetia boutoniana; Nigeria- Hoa Costus spectabilis; Nam Phi- Hoa Protea cynaroides; Ghana - Hoa Chà là; Sudan- Hoa Dâm buṭ ; Sêngal -Hoa Bao Báp; Tusinia- Hoa Nhài; Zimbabwe – Hoa Ly ngoṇ lử a (Flame lily); Ghana - Hoa Chà Là, Madagascar- Hoa Traṇ g Nguyên, Maroc- Hoa hồng Hoa Trochetia Hoa Ly ngọn lửa Hoa Zantadeschia rehmannii boutoniana Hoa Costus spectabilis Hoa Protea cynaroides Quốc hoa ở các nướ c Châu Á là: Bangladesh - Hoa Súng trắng (Nymphaea nouchali) Hoa Súng trắng Bhutan- Hoa Diếp lớ n (Meconopsis grandis) ; Brunei- Hoa Sổ vàng (Dillenia suffruticosa); Cambodia - Hoa Romduol (Mitrella mesnyi) Hoa Sổ vàng Hoa Mâũ Đơn Hoa Romduol Hoa Diếp lớ n Trung Quốc không chính thứ c có quốc hoa, có nơi dùng Hoa Mẫu Đơn (Quốc hoa từ đờ i Nhà Thanh), có nơi dùng Hoa Mai, có nơi dùng hoa Hướ ng Dương; Đài Loan (TQ)-Hoa Mâṇ ; Hồng Công (TQ)- Hoa Móng bò tím (Bauhinia blakeana); Ma Cao (TQ)- Hoa Sen; Ấn Độ -Hoa Sen trắng hồng (Nelumbo nucifera) Hoa Bauhinia blakeana Hoa Nelumbo nucifera Iran- Hoa Tulip; Iraq- Hoa hồng; Israel- Hoa Anh Thảo-Cyclamen (Rakefet) Hoa Anh Thảo Hoa Ratchaphruek Jordan- Hoa Đuôi diều đen (Iris chrysographes); Nhâṭ Bản- Hoa Anh Đào và Hoa Cúc, Triều -

Evaluación Del Riesgo Volcánico En El Sur Del Perú

EVALUACIÓN DEL RIESGO VOLCÁNICO EN EL SUR DEL PERÚ, SITUACIÓN DE LA VIGILANCIA ACTUAL Y REQUERIMIENTOS DE MONITOREO EN EL FUTURO. Informe Técnico: Observatorio Vulcanológico del Sur (OVS)- INSTITUTO GEOFÍSICO DEL PERÚ Observatorio Vulcanológico del Ingemmet (OVI) – INGEMMET Observatorio Geofísico de la Univ. Nacional San Agustín (IG-UNSA) AUTORES: Orlando Macedo, Edu Taipe, José Del Carpio, Javier Ticona, Domingo Ramos, Nino Puma, Víctor Aguilar, Roger Machacca, José Torres, Kevin Cueva, John Cruz, Ivonne Lazarte, Riky Centeno, Rafael Miranda, Yovana Álvarez, Pablo Masias, Javier Vilca, Fredy Apaza, Rolando Chijcheapaza, Javier Calderón, Jesús Cáceres, Jesica Vela. Fecha : Mayo de 2016 Arequipa – Perú Contenido Introducción ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Objetivos ............................................................................................................................................ 3 CAPITULO I ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Volcanes Activos en el Sur del Perú ........................................................................................ 4 1.1 Volcán Sabancaya ............................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Misti .................................................................................................................................. -

1 Living with Glaciers, Adapting to Change the Experience of The

Living with glaciers, adapting to change the experience of the Illimani project in Bolivia J. C. Alurralde, E. Ramirez, M. García, P. Pacheco, D. Salazar, R.S. Mamani Proyecto Illimani, UMSA – AGUA SUSTENTABLE, Bolivia Abstract Glaciers retreat’s rate and its impact on rural livelihoods in the tropical Andes were studied and modeled. Tropical glaciers are more affected by climate change than their temperate counterparts due to larger sun exposure and the coincidence of the rainy season with the summer which reduces snow accumulation. Global warming is occurring faster at high altitudes, causing glaciers’ shrinking and affecting downstream communities’ livelihoods where glaciers, important natural water regulators, are the only domestic and productive water source during dry seasons. Changing crop patterns and upward expanding of productive areas are also effects of the climate change. The project studies the Illimani dependent area in a physical and socio-productive context to evaluate its vulnerability to climate change and climate variability, and the already taken autonomous adaptation strategies. Multidisciplinary results are integrated in watershed management models to develop technically and socially validated descriptions of the dynamics between the glacier and the basin, for actual and future scenarios, resulting in proposals for adaptation actions. The findings reveal that climate is not the only triggering factor for autonomous adaptation and the strong heterogeneity of adaptation requirements in mountainous areas even within -

Contents Contents

Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU CONTENTS CONTENTS PERU, THE NATURAL DESTINATION BIRDS Northern Region Lambayeque, Piura and Tumbes Amazonas and Cajamarca Cordillera Blanca Mountain Range Central Region Lima and surrounding areas Paracas Huánuco and Junín Southern Region Nazca and Abancay Cusco and Machu Picchu Puerto Maldonado and Madre de Dios Arequipa and the Colca Valley Puno and Lake Titicaca PRIMATES Small primates Tamarin Marmosets Night monkeys Dusky titi monkeys Common squirrel monkeys Medium-sized primates Capuchin monkeys Saki monkeys Large primates Howler monkeys Woolly monkeys Spider monkeys MARINE MAMMALS Main species BUTTERFLIES Areas of interest WILD FLOWERS The forests of Tumbes The dry forest The Andes The Hills The cloud forests The tropical jungle www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 1 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU ORCHIDS Tumbes and Piura Amazonas and San Martín Huánuco and Tingo María Cordillera Blanca Chanchamayo Valley Machu Picchu Manu and Tambopata RECOMMENDATIONS LOCATION AND CLIMATE www.peru.org.pe [email protected] 2 Traveler’s Guide WILDLIFE WATCHINGTraveler’s IN PERU Guide WILDLIFE WATCHING IN PERU Peru, The Natural Destination Peru is, undoubtedly, one of the world’s top desti- For Peru, nature-tourism and eco-tourism repre- nations for nature-lovers. Blessed with the richest sent an opportunity to share its many surprises ocean in the world, largely unexplored Amazon for- and charm with the rest of the world. This guide ests and the highest tropical mountain range on provides descriptions of the main groups of species Pthe planet, the possibilities for the development of the country offers nature-lovers; trip recommen- bio-diversity in its territory are virtually unlim- dations; information on destinations; services and ited. -

Condoriri East Peak, Illampu West Face, and Climbs in the Apolobamba

Condoriri East Peak, Illampu West Face, and Climbs in the Apolobamba. The 1997 University of Edinburgh Apolobamba Expedition comprised Tom Bridgeland, Sam Chinnery, Rob Goodier, Jane McKay, Heather Smith and me. We spent July and August climbing in Bolivia’s Cordillera Real and the Apolobamba Range. We first went to the Condoriri area and climbed Pequeño Alpamayo (5370m) and the main summit of Condoriri (5648m) by the normal routes. Condoriri’s East Peak (Ala Derecha, 5330m) has four prominent couloirs visible from base camp. The right-hand couloir is the most obvious and was climbed by Mesili in 1976, but now appears to be badly melted out. On July 16, Sam and I climbed the narrow left-most couloir (Scottish VI/6,450m) of the four (possible second ascent). This was an excellent line, reminiscent of classic Scottish gully routes. There were three sections of vertical ice and a hard mixed section where the ice was discontinuous. We think this is probably the Couloir Colibri climbed by Gabbarou and Astier in 1989 (who reportedly found it hard). On the same day Rob and Tom climbed the second couloir (Scottish III/4, 450m) from the left (sans ropes), which was mostly névé with sections of steeper ice. It was probably a first ascent. On July 19, Jane and Heather climbed Huayna Potosi (6088m) by the normal route on the east side, while Rob, Tom, Sam and I climbed the West Face (1000m of 55° névé). Jane and Heather then climbed Illimani (6438m) by the standard route. After this Sam and I traveled to the Illampu region, and on the east side of the range we climbed, together with Jenz Richter, the Austrian Route on Pico del Norte (6045m). -

Dirección De Preparación Cepig

DIRECCIÓN DE PREPARACIÓN CEPIG INFORME DE POBLACIÓN EXPUESTA ANTE CAÍDA DE CENIZAS Y GASES, PRODUCTO DE LA ACTIVIDAD DEL VOLCÁN UBINAS PARA ADOPTAR MEDIDAS DE PREPARACIÓN Fuente: La República ABRIL, 2015 1 INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE DEFENSA CIVIL (INDECI) CEPIG Informe de población expuesta ante caída de cenizas y gases, producto de la actividad del volcán Ubinas para adoptar medidas de preparación. Instituto Nacional de Defensa Civil. Lima: INDECI. Dirección de Preparación, 2015. Calle Dr. Ricardo Angulo Ramírez Nº 694 Urb. Corpac, San Isidro Lima-Perú, San Isidro, Lima Perú. Teléfono: (511) 2243600 Sitio web: www.indeci.gob.pe Gral. E.P (r) Oscar Iparraguirre Basauri Director de Preparación del INDECI Ing. Juber Ruiz Pahuacho Coordinador del CEPIG - INDECI Equipo Técnico CEPIG: Lic. Silvia Passuni Pineda Lic. Beneff Zuñiga Cruz Colaboradores: Pierre Ancajima Estudiante de Ing. Geológica 2 I. JUSTIFICACIÓN En el territorio nacional existen alrededor de 400 volcanes, la mayoría de ellos no presentan actividad. Los volcanes activos se encuentran hacia el sur del país en las regiones de Arequipa, Moquegua y Tacna, en parte de la zona volcánica de los Andes (ZVA), estos son: Coropuna, Valle de Andagua, Hualca Hualca, Sabancaya, Ampato, Misti en la Región Arequipa; Ubinas, Ticsani y Huaynaputina en la región Moquegua, y el Yucamani y Casiri en la región Tacna. El Volcán Ubinas es considerado el volcán más activo que tiene el Perú. Desde el año 1550, se han registrado 24 erupciones aprox. (Rivera, 2010). Estos eventos se presentan como emisiones intensas de gases y ceniza precedidos, en algunas oportunidades, de fuertes explosiones. Los registros históricos señalan que el Volcán Ubinas ha presentado un Índice máximo de Explosividad Volcánica (IEV) (Newhall & Self, 1982) de 3, considerado como moderado a grande.