November 1960

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ariadne and Dionysus

Ariadne and Dionysus. Foreword. The Greek legends, as we know them from Homer, Hesiod, and other ancient sources, have their origins in the Bronze Age about the time of the thirteenth century B.C., which is when many scholars think something resembling the Trojan War may have taken place. The biblical Abraham may be of the same period. It was a time when the concept of Earth as the great Mother-Goddess, immanent in all things as all things were in Her, was being replaced throughout the region by the idea of an external Sky God, probably introduced by the marauding nom- adic tribes coming down from the north. At the same time, and for the same reasons, the principle of matriarchy was being replaced by patriarchy. The transformation was slow and spor- adic but eventually complete, at least on the surface. The legends, repeated by story-tellers for centuries before they were written down, probably with many deviations from the original, were meant to be pleasing to men. It has been my object to imagine the same events from the point of view of the women concerned. To this end I have added "fictional" material of my own. The more familiar version of the story of Ariadne and Dionysus is that she married him after being abandoned by Theseus. Dionysus was either man or god, as with many of the old myth- ical characters. I have imagined that she gave birth to him. Some may complain of the way I tell it, but after so long a time, who knows? In all the legends there are different known versions. -

Annotated Books Received

ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED A SUPPLEMENT OF TRANSLATION REVIEW Volume 9, No. 2 December 2003 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to Translation Review The University of Texas at Dallas Box 830688 - JO51 Richardson, TX 75083-0688 Telephone: (972) 883-2092 or 883-2093 Fax: (972) 883-6303, e-mail: [email protected] Annotated Books Received, published twice a year, is a Supplement of Translation Review, a joint publication of the American Literary Translators Association and the Center for Translation Studies at The University of Texas at Dallas. ISSN 0737-4836 Copyright © 2003 by Translation Review. The University of Texas at Dallas is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer. ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Arabic...................................................................................................................................1 Bosnian ................................................................................................................................1 Bulgarian..............................................................................................................................1 Catalan .................................................................................................................................1 Chinese.................................................................................................................................1 Dutch....................................................................................................................................4 -

Matthew Herrald

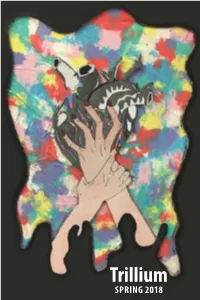

Trillium Issue 39, 2018 The Trillium is the literary and visual arts publication of the Glenville State College Department of Language and Literature Jacob Cline, Student Editor Heather Coleman, Art Editor Dr. Jonathan Minton, Faculty Advisor Dr. Marjorie Stewart, Co-Advisor Dustin Crutchfield, Designer Cover Artwork by Cearra Scott The Trillium welcomes submissions and correspondence from Glenville State College students, faculty, staff, and our extended creative community. Trillium Department of Language and Literature Glenville State College 200 High Street | Glenville, WV 26351 [email protected] http://www.glenville.edu/life/trillium.php The Trillium acquires printing rights for all published materials, which will also be digitally archived. The Trillium may use published artwork for promotional materials, including cover designs, flyers, and posters. All other rights revert to the authors and artists. POETRY Alicia Matheny 01 Return To Expression Jonathan Minton 02 from LETTERS Wayne de Rosset 03 Healing On the Way Brianna Ratliff 04 Untitled Matthew Herrald 05 Cursed Blood Jared Wilson 06 The Beast (Rise and Fall) Brady Tritapoe 09 Book of Knowledge Hannah Seckman 12 I Am Matthew Thiele 13 Stop Making Sense Logan Saho 15 Consequences Megan Stoffel 16 One Day Kerri Swiger 17 The Monsters Inside of Us Johnny O’Hara 18 This Love is Alive Paul Treadway 19 My Mistress Justin Raines 20 Patriotism Kitric Moore 21 The Day in the Life of a College Student Carissa Wood 22 7 Lives of a House Cat Hannah Curfman 23 Earth’s Pure Power Jaylin Johnson 24 Empty Chairs William T. K. Harper 25 Graffiti on the Poet Lauriat’s Grave Kristen Murphy 26 Mama Always Said Teddy Richardson 27 Flesh of Ash Randy Stiers 28 Fussell Said; Caroline Perkins 29 RICHWOOD Sam Edsall 30 “That Day” PROSE Teddy Richardson 33 The Fall of McBride Logan Saho 37 Untitled Skylar Fulton 39 Prayer Weeds David Moss 41 Hot Dogs Grow On Trees Hannah Seckman 42 Of Teeth Berek Clay 45 Lost Beach Sam Edsall 46 Black Magic 8-Ball ART Harold Reed 57 Untitled Maurice R. -

FULL LIST of WINNERS the 8Th International Children's Art Contest

FULL LIST of WINNERS The 8th International Children's Art Contest "Anton Chekhov and Heroes of his Works" GRAND PRIZE Margarita Vitinchuk, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “The Lucky One” Age Group: 14-17 years olds 1st place awards: Anna Lavrinenko, aged 14 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Ward No. 6” Xenia Grishina, aged 16 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chameleon” Hei Yiu Lo, aged 17 Hongkong for “The Wedding” Anastasia Valchuk, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Ward Number 6” Yekaterina Kharagezova, aged 15 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Portrait of Anton Chekhov” Yulia Kovalevskaya, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Oversalted” Valeria Medvedeva, aged 15 Serov, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Russia for “Melancholy” Maria Pelikhova, aged 15 Penza, Russia for “Ward Number 6” 1 2nd place awards: Anna Pratsyuk, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “Fat and Thin” Maria Markevich, aged 14 Gomel, Byelorussia for “An Important Conversation” Yekaterina Kovaleva, aged 15 Omsk, Russia for “The Man in the Case” Anastasia Dolgova, aged 15 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Happiness” Tatiana Stepanova, aged 16 Novocherkassk, Rostov Oblast, Russia for “Kids” Katya Goncharova, aged 14 Gatchina, Leningrad Oblast, Russia for “Chekhov Reading Out His Stories” Yiu Yan Poon, aged 16 Hongkong for “Woman’s World” 3rd place awards: Alexander Ovsienko, aged 14 Taganrog, Russia for “A Hunting Accident” Yelena Kapina, aged 14 Penza, Russia for “About Love” Yelizaveta Serbina, aged 14 Prokhladniy, Kabardino-Balkar Republic, Russia for “Chameleon” Yekaterina Dolgopolova, aged 16 Sovetsk, Kaliningrad Oblast, Russia for “The Black Monk” Yelena Tyutneva, aged 15 Sayansk, Irkutsk Oblast, Russia for “Fedyushka and Kashtanka” Daria Novikova, aged 14 Smolensk, Russia for “The Man in a Case” 2 Masha Chizhova, aged 15 Gatchina, Russia for “Ward No. -

Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre

The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre Florence Goyet THE CLASSIC SHORT STORY The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925 Theory of a Genre Florence Goyet http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Florence Goyet This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that she endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Goyet, Florence. The Classic Short Story, 1870-1925: Theory of a Genre. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0039 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/199#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available on our website at http://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/199#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-909254-75-6 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-909254-76-3 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-909254-77-0 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-909254-78-7 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 978-1-909254-79-4 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0039 Cover portraits (left to right): Henry James, Flickr Commons (http://www.flickr.com/photos/7167652@ N06/2871171944/), Guy de Maupassant, Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guy_ de_Maupassant_fotograferad_av_Félix_Nadar_1888.jpg), Giovanni Verga, Wikimedia (http:// commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catania_Giovanni_Verga.jpg), Anton Chekhov, Wikimedia (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Anton_Chekov_1901.jpg) and Akutagawa Ryūnosuke, Wikimedia (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Akutagawa_Ryunosuke_photo.jpg). -

Cover No Spine

2006 VOL 44, NO. 4 Special Issue: The Hans Christian Andersen Awards 2006 The Journal of IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People Editors: Valerie Coghlan and Siobhán Parkinson Address for submissions and other editorial correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] Bookbird’s editorial office is supported by the Church of Ireland College of Education, Dublin, Ireland. Editorial Review Board: Sandra Beckett (Canada), Nina Christensen (Denmark), Penni Cotton (UK), Hans-Heino Ewers (Germany), Jeffrey Garrett (USA), Elwyn Jenkins (South Africa),Ariko Kawabata (Japan), Kerry Mallan (Australia), Maria Nikolajeva (Sweden), Jean Perrot (France), Kimberley Reynolds (UK), Mary Shine Thompson (Ireland), Victor Watson (UK), Jochen Weber (Germany) Board of Bookbird, Inc.: Joan Glazer (USA), President; Ellis Vance (USA),Treasurer;Alida Cutts (USA), Secretary;Ann Lazim (UK); Elda Nogueira (Brazil) Cover image:The cover illustration is from Frau Meier, Die Amsel by Wolf Erlbruch, published by Peter Hammer Verlag,Wuppertal 1995 (see page 11) Production: Design and layout by Oldtown Design, Dublin ([email protected]) Proofread by Antoinette Walker Printed in Canada by Transcontinental Bookbird:A Journal of International Children’s Literature (ISSN 0006-7377) is a refereed journal published quarterly by IBBY,the International Board on Books for Young People, Nonnenweg 12 Postfach, CH-4003 Basel, Switzerland tel. +4161 272 29 17 fax: +4161 272 27 57 email: [email protected] <www.ibby.org>. Copyright © 2006 by Bookbird, Inc., an Indiana not-for-profit corporation. Reproduction of articles in Bookbird requires permission in writing from the editor. Items from Focus IBBY may be reprinted freely to disseminate the work of IBBY. -

The Good Doctor: the Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (And Others)

Vol. 33, No. 1 11 Literature and the Arts in Medical Education Johanna Shapiro, PhD Feature Editor Editor’s Note: In this column, teachers who are currently using literary and artistic materials as part of their curricula will briefly summarize specific works, delineate their purposes and goals in using these media, describe their audience and teaching strategies, discuss their methods of evaluation, and speculate about the impact of these teaching tools on learners (and teachers). Submissions should be three to five double-spaced pages with a minimum of references. Send your submissions to me at University of California, Irvine, Department of Family Medicine, 101 City Drive South, Building 200, Room 512, Route 81, Orange, CA 92868-3298. 949-824-3748. Fax: 714-456- 7984. E-mail: [email protected]. The Good Doctor: The Literature and Medicine of Anton Chekhov (and Others) Lawrence J. Schneiderman, MD In the spring of 1985, I posted a anything to do with me. “I don’t not possible in this public univer- notice on the medical students’ bul- want a doctor who knows Chekhov, sity; our conference rooms are best letin board announcing a new elec- I want a doctor who knows how to described as Bus Terminal Lite. tive course, “The Good Doctor: The take out my appendix.” Fortunately, The 10 second-year students who Literature and Medicine of Anton I was able to locate two more agree- signed up that first year spent 2 Chekhov.” It was a presumptuous able colleagues from literature and hours each week with me for 10 announcement, since I had never theatre. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Dirty Work: Labor, Dissatisfaction and Everyday Life in Contemporary French Literature and Culture (1975-present) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9586x4bj Author Fronsman-Cecil, Dorthea Margery Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Dirty Work: Labor, Dissatisfaction and Everyday Life in Contemporary French Literature and Culture (1975-present) A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies by Dorthea Margery Fronsman-Cecil 2018 © Copyright by Dorthea Margery Fronsman-Cecil 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Dirty Work: Labor, Dissatisfaction and Everyday Life in Contemporary French Literature and Culture (1975-present) by Dorthea Margery Fronsman-Cecil Doctor of Philosophy in French and Francophone Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Lia N. Brozgal, Chair “Dirty Work: Labor, Dissatisfaction and Everyday Life in Contemporary French Literature and Culture (1975-present),” is an analysis of the representation of everyday activities – namely, of work, leisure, and consumerism – in contemporary French novels and other cultural productions. This dissertation examines how these contemporary texts use narrative, generic, and stylistic experiments to represent cynicism and dissatisfaction with everyday life as the consequences of neoliberal -

Smoke Ivan Turgenev Smoke Ivan Turgenev

Smoke Ivan Turgenev Smoke Ivan Turgenev Translated by Constance Garnett THE NAMES OF THE CHARACTERS IN THE BOOK Grigóry [Grísha] Mihálovitch Litvínov. Tat-yána [Tánya] Petróvna Shestóv. Kapitolína Márkovna. Rostisláv Bambáev. Semyón Yákovlevitch Voroshílov. Stepán Nikoláevitch Gubar-yóv. Matróna Semyónovna Suhántchikov. Tit Bindásov. Pish-Tchálkin. Sozónt Ivánitch Potúgin. Irína Pávlovna Osínin. Valerián Vladímirovitch Ratmírov. I On the 10th of August 1862, at four o’clock in the afternoon, a great number of people were thronging before the well-known Konversation in Baden-Baden. The weather was lovely; everything around—the green trees, the bright houses of the gay city, and the undulating outline of the mountains—everything was in holiday mood, basking in the rays of the kindly sunshine; everything seemed smiling with a sort of blind, 1 Smoke Ivan Turgenev confiding delight; and the same glad, vague smile strayed over the human faces too, old and young, ugly and beautiful alike. Even the blackened and whitened visages of the Parisian demi-monde could not destroy the general impression of bright content and elation, while their many-coloured ribbons and feathers and the sparks of gold and steel on their hats and veils involuntarily recalled the intensified brilliance and light fluttering of birds in spring, with their rainbow-tinted wings. But the dry, guttural snapping of the French jargon, heard on all sides could not equal the song of birds, nor be compared with it. Everything, however, was going on in its accustomed way. The orchestra in the Pavilion played first a medley from the Traviata, then one of Strauss’s waltzes, then ‘Tell her,’ a Russian song, adapted for instruments by an obliging conductor. -

How Much Land Does a Man Need? by Leo Tolstoy

Lesson Ideas English Language Arts 6-12 How much land does a man need? By Leo Tolstoy How much land does a man need? is a short story written by Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910). In the story, Tolstoy reflects critically on the hierarchy of 19th century Russian society where the poor were deprived and the rich stayed wealthy. Personal belongings, property, and other forms of material wealth were measures of an individual’s worth and determined social class. Land shortage was a major issue in 19th century Russia, and in his story, Tolstoy associates the Devil with the main character’s greed for land. How much land does a man need? inspires discussion about the concepts of how greed and both socio-economic inequalities and injustices can contribute to our desire to “have more,” even if it means taking risks. The story also calls into question additional topics that students can apply to their own lives such as how we anticipate and justify the consequences of our actions when fueled by greed or other motivations. Many of these themes serve a double purpose as they are also relevant to building gambling literacy and competencies. After all, being able to identify our own tendencies toward greed can help us pause and perhaps rethink our decisions. And being mindful that we are more than our wealth can release us of the burden of comparing our and others’ financial value. Pahom sets out to encircle so much land that by the Brief summary afternoon he realizes he has created too big of a circuit. -

Doak, C. (2016). What's Papa For? Paternal Intimacy and Distance In

Doak, C. (2016). What’s Papa For? Paternal Intimacy and Distance in Chekhov’s Early Stories. Slavic and East European Journal, 59(4), 517-543. Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): Unspecified Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document Publisher allows a PDF copy of final published version to be deposited in institutional repository. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ SEEJ_59_4_9V 1/13/2016 6:56 PM Page 517 WHAT’S PAPA FOR? PATERNAL INTIMACY AND DISTANCE IN CHEKHOV’S EARLY STORIES Connor Doak, University of Bristol, United Kingdom In Anton Chekhov’s 1886 story “Grisha,” the eponymous child protagonist thinks of his father as an “extremely mysterious person.”1 While Grisha un- derstands the role of his mother and nanny—“they feed [him], dress him, and put him to bed”—he remains puzzled as to the existential purpose of his fa- ther.2 “But as for Papa,” the narrative continues, “no-one knows what he’s there for.”3 Grisha’s confusion about his father’s purpose provides one example of a fa- miliar narrative device in Chekhov’s stories: adopting a child’s point of view to provide a defamiliarizing perspective on society and accepted social con- ventions (Loehlin 40–41; Laponina). Specifically, Grisha’s naive comment defamiliarizes the position of the father in the nineteenth-century home, caus- ing the reader to ponder over the father’s responsibilities. -

EDUCATION PACK 1 Bristol Old Vic | the Cherry Orchard | Education Pack “A Poem About Life and Death and Transition and Change” PETER BROOK, 1981

EDUCATION PACK 1 Bristol Old Vic | The Cherry Orchard | Education Pack “A poem about life and death and transition and change” PETER BROOK, 1981 FOREWORD CONTENTS The Cherry Orchard was written over a hundred 2. Introduction years ago and the dominant issue of anxiety and 3. Chekhov, A History change are still with us in a tumultuous twenty-first century. As teachers, we are in a position where we 5. Exploring the Story can challenge ideas and stimulate discussion within 7. Dissecting the Characters our classrooms while exploring a wide range of performance opportunities. This is a play where 9. A Note from the Director seemingly very little happens on stage but events of 11. A Note from the Designer rapid economic and cultural change are happening all around. We know the old way of life is doomed 13. The Moscow Arts Theatre but are not sure whether the new dawn will 14. Under the Microscope ultimately be any better than that which is being cast aside. 15. Key Themes This is a play of many contradictions and is wide 16. How to Write a Review open to a director’s interpretation. Does the future 17. Activities look bleak or alluring? Chekhov wrote The Cherry Orchard while he was dying and knew that this would be his last play. Does this create an air of melancholy? How does this sit with the conjuring tricks and circus skills in this self-declared ‘comedy in four acts’? Is it a naturalistic or symbolic play or a combination of the two? We can decide on any one or all of these interpretations and each are as Introduction valid as any other.