Dancing Rejang and Being Maju

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

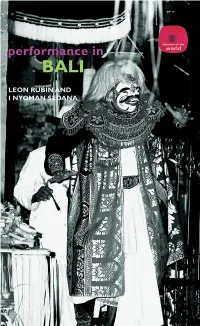

Performance in Bali

Performance in Bali Performance in Bali brings to the attention of students and practitioners in the twenty-first century a dynamic performance tradition that has fasci- nated observers for generations. Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out. The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali: • Wayang shadow-puppet theatre • Sanghyang ritual trance performance • Gambuh classical dance-drama • the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre. The book is a guide to current practice, with detailed analyses of recent theatrical performances looking at all aspects of performance, production and reception. There is a focus on the examination and description of the actual techniques used in the training of performers, and how some of these techniques can be applied to Western training in drama and dance. The book also explores the relationship between improvisation and rigid dramatic structure, and the changing relationships between contemporary approaches to performance and traditional heritage. These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intel- lectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer. Leon Rubin is Director of East 15 Acting School, University of Essex. I Nyoman Sedana is Professor at the Indonesian Arts Institute (ISI) in Bali, Indonesia. Contents List -

An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume -� Focus� On� The� Legong� Dance� Costume

Print ISSN 1229-6880 Journal of the Korean Society of Costume Online ISSN 2287-7827 Vol. 67, No. 4 (June 2017) pp. 38-57 https://doi.org/10.7233/jksc.2017.67.4.038 An Analysis of the Characteristics of Balinese Costume - Focus on the Legong Dance Costume - Langi, Kezia-Clarissa · Park, Shinmi⁺ Master Candidate, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University Associate Professor, Dept. of Clothing & Textiles, Andong National University⁺ (received date: 2017. 1. 12, revised date: 2017. 4. 11, accepted date: 2017. 6. 16) ABSTRACT1) Traditional costume in Indonesia represents identity of a person and it displays the origin and the status of the person. Where culture and religion are fused, the traditional costume serves one of the most functions in rituals in Bali. This research aims to analyze the charac- teristics of Balinese costumes by focusing on the Legong dance costume. Quantitative re- search was performed using 332 images of Indonesian costumes and 210 images of Balinese ceremonial costumes. Qualitative research was performed by doing field research in Puri Saba, Gianyar and SMKN 3 SUKAWATI(Traditional Art Middle School). The paper illus- trates the influence and structure of Indonesian traditional costume. As the result, focusing on the upper wear costume showed that the ancient era costumes were influenced by animism. They consist of tube(kemben), shawl(syal), corset, dress(terusan), body painting and tattoo, jewelry(perhiasan), and cross. The Modern era, which was shaped by religion, consists of baju kurung(tunic) and kebaya(kaftan). The Balinese costume consists of the costume of participants and the costume of performers. -

Performance in Bali

Performance in Bali Performance in Bali brings to the attention of students and practitioners in the twenty-first century a dynamic performance tradition that has fasci- nated observers for generations. Leon Rubin and I Nyoman Sedana, both international theatre professionals as well as scholars, collaborate to give an understanding of performance culture in Bali from inside and out. The book describes four specific forms of contemporary performance that are unique to Bali: • Wayang shadow-puppet theatre • Sanghyang ritual trance performance • Gambuh classical dance-drama • the virtuoso art of Topeng masked theatre. The book is a guide to current practice, with detailed analyses of recent theatrical performances looking at all aspects of performance, production and reception. There is a focus on the examination and description of the actual techniques used in the training of performers, and how some of these techniques can be applied to Western training in drama and dance. The book also explores the relationship between improvisation and rigid dramatic structure, and the changing relationships between contemporary approaches to performance and traditional heritage. These culturally unique and beautiful theatrical events are contextualised within religious, intel- lectual and social backgrounds to give unparalleled insight into the mind and world of the Balinese performer. Leon Rubin is Director of East 15 Acting School, University of Essex. I Nyoman Sedana is Professor at the Indonesian Arts Institute (ISI) in Bali, Indonesia. Theatres of the World Series editor: John Russell Brown Series advisors: Alison Hodge, Royal Holloway, University of London; Osita Okagbue, Goldsmiths College, University of London Theatres of the World is a series that will bring close and instructive contact with makers of performances from around the world. -

Pola Lantai Panggung Un Dan Kompetensi Dasar Yang Tercantum Dalam Kurikulum

Alien Wariatunnisa Yulia Hendrilianti Seni Tari Seni Seni S e untukuntuk SSMA/MAMA/MA KKelaselas XX,, XXI,I, ddanan XXIIII n i Tari untuk SMA/MA Kelas X, XI, dan XII untuk SMA/MA u nt u Yulia Hendrilianti Yulia Alien Wariatunnisa PUSAT PERBUKUAN Kementerian Pendidikan Nasional Hak Cipta buku ini pada Kementerian Pendidikan Nasional. Dilindungi Undang-undang. Penulis Alien Wariatunnisa Seni Tari Yulia Hendrilianti untuk SMA/MA Kelas X, XI, dan XII Penyunting Isi Irma Rahmawati Penyunting Bahasa Ria Novitasari Penata Letak Irma Pewajah Isi Joni Eff endi Daulay Perancang Sampul Yusuf Mulyadin Ukuran Buku 17,6 x 25 cm 792.8 ALI ALIEN Wiriatunnisa s Seni Tari untuk SMA/MA Kelas X, XI, dan XII/Alien Wiriatunnisa, Yulia Hendrilianti; editor, Irma Rahmawati, Ria Novitasari.—Jakarta: Pusat Perbukuan, Kementerian Pendidikan Nasional, 2010. xii, 230 hlm.: ilus.; 30 cm Bibliograę : hlm. 228 Indeks ISBN 978-979-095-260-7 1. Tarian - Studi dan Pengajaran I. Judul II. Yulia Hendrilianti III. Irma Rahmawati IV. Ria Novitasari Hak Cipta Buku ini dialihkan kepada Kementerian Pendidikan Nasional dari Penerbit PT Sinergi Pustaka Indonesia Diterbitkan oleh Pusat Perbukuan Kementerian Pendidikan Nasional Tahun 2010 Diperbanyak oleh... Kata Sambutan Puji syukur kami panjatkan ke hadirat Allah SWT, berkat rahmat dan karunia-Nya, Pemerintah, dalam hal ini, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, pada tahun 2009, telah membeli hak cipta buku teks pelajaran ini dari penulis/penerbit untuk disebarluaskan kepada masyarakat melalui situs internet (website) Jaringan Pendidikan Nasional. Buku teks pelajaran ini telah dinilai oleh Badan Standar Nasional Pendidikan dan telah ditetapkan sebagai buku teks pelajaran yang memenuhi syarat kelayakan untuk digunakan dalam proses pembelajaran melalui Peraturan Menteri Pendidikan Nasional Nomor 49 Tahun 2009 tanggal 12 Agustus 2009. -

SPECIAL ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS the Dynamics of Rejang Renteng

Linggih & Sudarsana. Space and Culture, India 2020, 7:4 Page | 45 https://doi.org/10.20896/saci.v7i4.580 SPECIAL ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS The Dynamics of Rejang Renteng Dance in Bali as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of the World I Nyoman Linggih† and I Ketut Sudarsana†* Abstract This current study is intended to interpret a Balinese cultural product which has taken root in and connected to the Hindu religious system, namely the Rejang Renteng dance. Apart from becoming a cultural product, it also functions as a social cohesion as it involves a significant number of dancers who are children, women, elderly people and the homemakers who become the members of an organisation known referred to as PKK (Family Welfare Education). They interact with one another. The growth and development of the dance have been used as the icon of every Hindu religious activity in Bali, and also as an icon of different social activities. The question is why the Rejang Renteng dance has developed more rapidly than the other dance forms. This current study is also intended to answer different matters on the Rejang Renteng dance, which cannot be separated from the dynamics of the development of the Balinese society which is changing in the current globalisation era. It is also intended to explore the shift in its meaning, function and, which has taken place from the beginning until the current times. The current study was conducted at Masceti Temple Gianyar, Karangasem and Denpasar. The qualitative method, especially the observation, interview and documentary techniques, were applied to collect the data. -

Music As Episteme, Text, Sign & Tool: Comparative Approaches To

I would like to dedicate this work firstly to Sue Achimovich, my mother, without whose constant support I wouldn’t have been able to have jumped across the abyss and onto the path; I would also like to dedicate the work to Dr Saskia Kersenboom who gave me the light and showed me the way; Finally I would like to dedicate the work to both Patrick Eecloo and Guy De Mey who supported me when I could have fallen over the edge … This edition is also dedicated to Jaak Van Schoor who supported me throughout the creative process of this work. Foreword This work has been produced thanks to more than four years of work. The first years involved a great deal of self- questioning; moving from being an active creative artist—a composer and performer of experimental music- theatre—to being a theoretician has been a long journey. Suffice to say, on the gradual process which led to the ‘composition’ of this work, I went through many stages of looking back at my own creative work to discover that I had already begun to answer many of the questions posed by my new research into Balinese culture, communicating remarkable information about myself and the way I’ve attempted to confront my world in a physically embodied fashion. My early academic experiments, attending conferences and writing papers, involved at first largely my own compositional work. What I realise now is that I was on a journey towards developing a system of analysis which would be based on both artistic and scientific information, where ‘subjective’ experience would form an equally valid ‘product’ for analysis: it is, after all, only through our own personal experience that we can interface with the world. -

Plloce GS IIITEWTIONAL Oon-Fje'bbwgi

PllOCE GS IIITEWTIONAL ooN-FJe'BBWGI \'.elCT. l'i'liiU n~ N~st'Or T- ~a» Sf 1;11ttat 'I'l l,J"' I.IFSSO PROCEEDINGS INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE SOUTHEAST ASIANTHINKSHOP: THE QUESTION OFWO:RI,D CULTURE EDITORS I Ketut Ardhana • Yekti Maunati Michael Kuhn • Nestor T. Castro Diane Butler• Slamat Trisila I.IFSSO Center •of Bali Studies-Udayana University (UNUD) in collaboration with: lntemational Federation of Social Science Organizations (lFSSO), Social Sciences and Humanities Network (The WorldSSHNet) Supported by: Faculty of Cultural Sciences and Hurnanities·Udayana University • PROCEEDINGS INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE SOUTHEAST ASIAN THINKSHOP: THE QUESTION OF WORLD CULTURE EDITORS I Ketut Ardhana Yektl Maunati NestorT. Castro Michael Kuhn Diane Butler Slamat Trisila Publisher Center of Ball Studies Udayana University PB Sudinnan Street, Denpasar Bal!, Indonesia In collaboration with: International Fede radon of Social Science Organizations (lFSSO), Social Sciences and Humanities Network (The WorldSSHNet) Supported by: Faculty of Cultural Sciences and Humanlties·Udayana University First Edition: 2016 ISBN 978·602·60086·0·2 .. II TABLE OF CONTENT Preface from Organizing Committee - ix Foreword from World Social Science and Humanities - xi Foreword from the President of!FSSO - xiii Welcome Message from Rector Udayana University- xv Conference Program - xxi Participants - xxiv SMART, HERITAGE CITIES, ARCHITECTURE -1 Towards Smart Cities in the Context of Globalization: Challenges and Responses I Ketut Ardhana - 3 Marginalization of Farmers Post-Landsales -

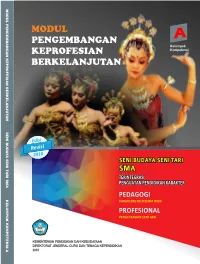

Modul Pengembangan Keprofesian Berkelanjutan

MODUL PENGEMBANGAN KEPROFESIAN BERKELANJUTAN KEPROFESIAN MODUL PENGEMBANGAN MODUL PENGEMBANGAN A Kelompok KEPROFESIAN Kompetensi BERKELANJUTAN SENI BUDAYA SENI TARI SMA SENI TARI SENI BUDAYA Edisi Revisi 2018 SENI BUDAYA SENI TARI SMA TERINTEGRASI PENGUATANPENDIDIKANKARAKTER PEDAGOGI KELOMPOK KOMPETENSI A KOMPETENSI KELOMPOK KARAKTERISTIK PESERTA DIDIK PROFESIONAL PENGETAHUAN SENI TARI KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN DIREKTORAT JENDERAL GURU DAN TENAGA KEPENDIDIKAN 2018 PEDAGOGI : KARAKTERISTIK PESERTA DIDIK 1. Penulis : Drs. Taufiq Eko Yanto 2. Editor Substansi : Winarto, M.Pd. 3. Editor Bahasa : Drs. Irene Nusanti, M.A. 4. Reviewer : Digna Sjamsiar, S.Pd. Bambang Setya Cipta, S.E, M.Pd. PROFESIONAL : PENGETAHUAN SENI TARI 1. Penulis : Dra. Lilin Candrawati S., M.Sn. 2. Editor Substnsi : Dr. I Gede Oka Subagia, M.Hum. 3. Editor Bahasa : Rohmat Sulistya, S.T., M.T. 4. Reviewer : Dra. Gusyamti, M.Pd. Dra. Lilin Candrawati S., M.Sn. Desian Grafis dan Ilustrasi: Tim Desain Grafis Copyright © 2018 Direktorat Pembinaan Guru Pendidikan Dasar Direktorat Jenderal Guru dan Tenaga Kependidikan Hak Cipta Dilindungi Undang-Undang Dilarang mengopi sebagian atau keseluruhan isi buku ini untuk kepentingan komersial tanpa izin tertulis dari Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. SAMBUTAN Peran guru profesional dalam proses pembelajaran sangat penting sebagai kunci keberhasilan belajar siswa. Guru profesional adalah guru yang kompeten membangun proses pembelajaran yang baik sehingga dapat menghasilkan pendidikan yang berkualitas dan berkarakter prima. Hal tersebut menjadikan guru sebagai komponen yang menjadi fokus perhatian pemerintah pusat maupun pemerintah daerah dalam peningkatan mutu pendidikan terutama menyangkut kompetensi guru. Pengembangan profesionalitas guru melalui Program Pengembangan Keprofesian Berkelanjutan merupakan upaya Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan melalui Direktorat Jenderal Guru dan Tenaga Kependikan dalam upaya peningkatan kompetensi guru. -

Jadwal Kegiatan Pesta Kesenian Bali Xli - 2019 1

JADWAL KEGIATAN PESTA KESENIAN BALI XLI - 2019 1. Saturday, 15th June 2019 Time : 14.00 (Mid Indonesian Time – MIT) Location : In front of the People Struggle Monument, Renon, Denpasar Program : Cultural Procession of the 41st Bali Arts Festival 2019 Time : 18.00 ( MIT ) Location : Madya Mandala Stage Program : Semara Pagulingan Musics of SMKN 4 Vocational High School, Bangli Regency Time : 20.00 ( MIT ) Location : Ardha Candra Amphitheatre, Arts Center Denpasar Program : - THE OPENING CEREMONY OF THE 41ST BALI ARTS FESTIVAL - 2019 - The Colossal Dance—Drama Sendratari “Bali Padma Bhuwana”, by the Indonesian Arts Institute – ISI of Denpasar 7 2. Sunday, 16th June 2019 Time : 11.00 MIT Location : ISI ( Indonesian Institute of Arts ) Denpasar Program : Contest of Flower and Janur (Coconut Leaves) Arrangement for PKK - Family Welfare (Women) Associations of Regencies and City throughout Bali Time : 11.00 MIT Location : Ratna Kanda Stage Program : Workshop on “ Ngunda Bayu ( Distribution of Energy )” in Dancing, Time : 14.00 MIT Location : Angsoka Stage Program : Workshop on Balinese Musics based on wind instrument Time : 17.00 MIT Location : in front of Kriya Hall Program : “Mala Renjana” dance, participation of the the Faculty of Language and Arts of Yogyakarta State University Time : 19.30 MIT Location : the area of the river and Ayodya Stage Program : Dance, Music and Poets of “ Nggo Wor Baido Na Nggomar “, participation of ISBI ( the Indonesian Institute of Culture ) of Papua Land Time : 19.30 MIT Location : Ksirarnawa Hall Program : Performance of Shamisen and Shakuhachi, Japanese Traditional Dances and Songs, participation of Mr. Baisho Matsumoto Time : 19.30 MIT Location : Ardha Candra Amphitheatre Program : Colossal Dance Drama – Legu Gendong, by the Artists Group of Printing Mas, representing Denpasar City 3. -

Seni Tari Jilid 2

Rahmida Setiawati SENI TARI JILID 2 SMK Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah Departemen Pendidikan Nasional Hak Cipta pada Departemen Pendidikan Nasional Dilindungi Undang-undang SENI TARI JILID 2 Untuk SMK Penulis Utama : Rahmida Setiawati Editor : Melina Suryadewi Perancang Kulit : Tim Ukuran Buku : 17,6 x 25 cm TIA SETIAWATI, Rahmida s Seni Tari untuk SMK Jilid 2 /oleh Rahmida Setiawati ---- Jakarta : Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan, Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, 2008. vii. 199 hlm Daftar Pustaka : A1-A4 Glosarium : E1-E9 ISBN : 978-979-060-026-3 Diterbitkan oleh Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah Departemen Pendidikan Nasional Tahun 2008 KATA SAMBUTAN Puji syukur kami panjatkan kehadirat Allah SWT, berkat rahmat dan karunia Nya, Pemerintah, dalam hal ini, Direktorat Pembinaan Sekolah Menengah Kejuruan Direktorat Jenderal Manajemen Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah Departemen Pendidikan Nasional, telah melaksanakan kegiatan penulisan buku kejuruan sebagai bentuk dari kegiatan pembelian hak cipta buku teks pelajaran kejuruan bagi siswa SMK. Karena buku-buku pelajaran kejuruan sangat sulit di dapatkan di pasaran. Buku teks pelajaran ini telah melalui proses penilaian oleh Badan Standar Nasional Pendidikan sebagai buku teks pelajaran untuk SMK dan telah dinyatakan memenuhi syarat kelayakan untuk digunakan dalam proses pembelajaran melalui Peraturan Menteri Pendidikan Nasional Nomor 45 Tahun 2008 tanggal 15 Agustus 2008. Kami menyampaikan penghargaan yang setinggi-tingginya kepada seluruh penulis yang telah berkenan mengalihkan hak cipta karyanya kepada Departemen Pendidikan Nasional untuk digunakan secara luas oleh para pendidik dan peserta didik SMK. Buku teks pelajaran yang telah dialihkan hak ciptanya kepada Departemen Pendidikan Nasional ini, dapat diunduh (download), digandakan, dicetak, dialihmediakan, atau difotokopi oleh masyarakat. -

National Inventory 11111111111111111111111111111 0061700030 R E~U CLT

/ 11111111111111111111111111111 0061700042 Reyu CLT / CIH IlTH Le 3 1 MARS 2014 No ......... 02.7~ ............. .. Re cu CLT ClH ITH f, C~ ~~-~-~;u ;~~5 I ~'/ ... .. National Inventory 11111111111111111111111111111 0061700030 R e~u CLT . CH \;i-1 ~-- · --..w~-• --..•---·-·---, j i Le ) 2 8 JAN. ~[ J5 i : l Extract of The lnventorie N° . ~0.1~3···---·-····j For Balinese, dancing is a part of religious ceremonies, conducted periodically according to the Balinese calendar. There are many types of dancing developed by the Balinese, which are found in the eight districts and one municipality within Bali Province. The Inventory Form attached to this nomination file consists of nine Balinese popular dances and considered to represent three large group dances and they are still well maintain. The inventory list includes 16 queries, they are: 1. Code of Inventory 2. Name of the element 3. Name of individu nominating the element 4. Place and Date of the elements have been reported 5. Agreement of the elements inventories from (a) community/organization/ association/body, (b) social groups or (c) individuals 6. Brief history of the element 7. Name of community/organization/association/body(ies)/social group/or individuals responsible of the element 8. Cultural teacher/maestro 9. Geographical location of the element 10. Identification of the elements 11. Brief description of the element 12. Conditions of the element 13. Safeguarding measures 14. Best Practices in safeguarding the elements 15. Documentation 16. References There are three large categories for Balinese dances, they are Wali, Bebalih, and Balih Balihan. For Wali, represented by three sacred dances which are performed most of the time in the inner sanctum of Balinese temples as part of ceremonies. -

Mapping of Batuan Tourism Area, Gianyar Bali

IJSEGCE VOL 2, No.3 November 2019 ISSN: 2656- 3037 http://www.journals.segce.com/index.php/IJSEGCE DOI: https://doi.org/10.1234/ijsegce.v2i3.127 MAPPING OF BATUAN TOURISM AREA, GIANYAR BALI I Made Wisma Okbar [email protected] Regional Development Planning and Environmental ManagementPostgraduate Program Mahasaraswati University Denpasar Ni Putu Pandawani [email protected] Regional Development Planning and Environmental ManagementPostgraduate Program Mahasaraswati University Denpasar Nyoman Utari Vipriyanti [email protected] Regional Development Planning and Environmental ManagementPostgraduate Program Mahasaraswati University Denpasar Wayan Maba [email protected] Regional Development Planning and Environmental ManagementPostgraduate Program Mahasaraswati University Denpasar ABSTRACT Minister of Tourism Regulation Number 10 of 2016, tourist attraction is everything that has a uniqueness, beauty, and value in the form of diversity of natural wealth, culture and man-made products that are the target and destination of tourist visits. The purpose of this study was to map the tourist destination of the BatuAdat village. The study was conducted in AdatBatuan Village, Sukawati District, Gianyar Regency, Bali Province. Sampling was done by purposive sampling technique, with a total sample of 30 people. Data were analyzed using Geographic Information System (GIS), then describe from the data, namely photographs of documents and cases that were then drawn conclusions. BatuAdatDesa tour package; village temples and puseh with classical dance performances:genggong, gambuh, shadow puppets, barong rangda, legong. Nextaround the village starts from the village temple / puseh headed west by using a bicycle or shuttle to visit thelocation pandekerisin Banjar Jeleka, continue to the south to visit the process of making barong rangda handicrafts, masks and shadow puppets located in Banjar Puaya, then to Banjar Pekandelan sees the Batuan style painting that has been visited during the making of bades and sacred buildings in Banjar Peninjoan.