The Ecumenical Movement and the Origins of the League Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

The New Woman Criminal in British Culture at the Fin De Siècle

FRAMED DIGITALCULTUREBOOKS is a collaborative imprint of the University of Michigan Press and the University of Michigan Library. FRAMED The New Woman Criminal in British Culture at the Fin de Siècle ELIZABETH CAROLYN MILLER The University of Michigan Press AND The University of Michigan Library ANN ARBOR Copyright © 2008 by Elizabeth Carolyn Miller All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press and the University of Michigan Library Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2011 2010 2009 2008 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Miller, Elizabeth Carolyn, 1974– Framed : the new woman criminal in British culture at the fin de siècle / Elizabeth Carolyn Miller. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-472-07044-2 (acid-free paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-07044-4 (acid-free paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-05044-4 (pbk. : acid-free paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-05044-3 (pbk. : acid-free paper) 1. Detective and mystery stories, English—History and criticism. 2. English fiction—19th century—History and criticism. 3. Female offenders in literature. 4. Terrorism in literature. 5. Consumption (Economics) in literature. 6. Feminism and literature— Great Britain—History—19th century. 7. Literature and society— Great Britain—History—19th century. -

Great Britain and Naval Arms Control: International Law and Security 1898-1914

The London School of Economics and Political Science Great Britain and Naval Arms Control: International Law and Security 1898-1914 by Scott Andrew Keefer A thesis submitted to Department of International History of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International History, London, December 30, 2011 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgment is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 99,939 words. 2 Abstract: This thesis traces the British role in the evolution of international law prior to 1914, utilizing naval arms control as a case study. In the thesis, I argue that the Foreign Office adopted a pragmatic approach towards international law, emphasizing what was possible within the existing system of law rather than attempting to create radically new and powerful international institutions. The thesis challenges standard perceptions of the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907 which interpreted these gatherings as unrealistic efforts at general disarmament through world government, positing instead that legalized arms control provided a realistic means of limiting armaments. -

Celeste Birkey

Celeste Birkey A little bit of information about Celeste: Celeste began attending Meadowbrook Church in 1990 and became a member August 2000. With her marriage to Joe Birkey in 2005, she has dual membership with both Meadowbrook and her husband’s church, East Bend Mennonite. She has participated on Meadowbrook mission trips twice to El Salvador and once to Czech Republic. Celeste grew up in the Air Force. Her father was a Master Sargent in the Air Force. Celeste and her mother moved with her father as his assignments allowed and took them around the world. She has lived or traveled to about 20 countries during her lifetime. During a trip to Israel, she was baptized in the Jordan River. Favorite Hymn- “I don’t have a favorite song or hymn, there are so many to choose from. I really enjoy the old hymns of the church. They give me encouragement in my walk with the Lord. The hymns also give me valuable theology lessons and advice from the saints of previous generations [hymn authors].” Celeste explains that hymnal lessons provide systematic theology in that it teaches her how to have intimacy with God, to know who God is, how she can relate to Him, what is required for salvation, what grace from God means, and how to walk in the spirit. Favorite Scripture- Psalm 125:1-2 “They that trust in the Lord shall be as Mount Zion which cannot be removed, but abideth forever. As the mountains are round about Jerusalem, so the Lord is round about His people from henceforth even forever.” This verse gives Celeste comfort in knowing God surrounds her with protection forever. -

STEPHEN TAYLOR the Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II

STEPHEN TAYLOR The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II in MICHAEL SCHAICH (ed.), Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007) pp. 129–151 ISBN: 978 0 19 921472 3 The following PDF is published under a Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND licence. Anyone may freely read, download, distribute, and make the work available to the public in printed or electronic form provided that appropriate credit is given. However, no commercial use is allowed and the work may not be altered or transformed, or serve as the basis for a derivative work. The publication rights for this volume have formally reverted from Oxford University Press to the German Historical Institute London. All reasonable effort has been made to contact any further copyright holders in this volume. Any objections to this material being published online under open access should be addressed to the German Historical Institute London. DOI: 5 The Clergy at the Courts of George I and George II STEPHEN TAYLOR In the years between the Reformation and the revolution of 1688 the court lay at the very heart of English religious life. Court bishops played an important role as royal councillors in matters concerning both church and commonwealth. 1 Royal chaplaincies were sought after, both as important steps on the road of prefer- ment and as positions from which to influence religious policy.2 Printed court sermons were a prominent literary genre, providing not least an important forum for debate about the nature and character of the English Reformation. -

The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Southern Methodist University, [email protected]

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Central University Libraries Award Documents 2019 The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Southern Methodist University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Oh, Amanda, "The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism" (2019). The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents. 10. https://scholar.smu.edu/weil_ura/10 This document is brought to you for free and open access by the Central University Libraries at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Larrie and Bobbi Weil Undergraduate Research Award Documents by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. The Latitudinarian Influence on Early English Liberalism Amanda Oh Professor Wellman HIST 4300: Junior Seminar 30 April 2018 Part I: Introduction The end of the seventeenth century in England saw the flowering of liberal ideals that turned on new beliefs about the individual, government, and religion. At that time the relationship between these cornerstones of society fundamentally shifted. The result was the preeminence of the individual over government and religion, whereas most of Western history since antiquity had seen the manipulation of the individual by the latter two institutions. Liberalism built on the idea that both religion and government were tied to the individual. Respect for the individual entailed respect for religious diversity and governing authority came from the assent of the individual. -

Down in Turkey, Far Away: Human Rights, the Armenian Massacres

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title "Down in Turkey, far away": human rights, the Armenian Massacres, and Orientalism in Wilhelmine Germany Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9403g47p Journal Journal of Modern History, 79(1) ISSN 0022-2801 Author Anderson, ML Publication Date 2007-03-01 DOI 10.1086/517545 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California “Down in Turkey, far away”: Human Rights, the Armenian Massacres, and Orientalism in Wilhelmine Germany Author(s): Margaret Lavinia Anderson Source: The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 79, No. 1 (March 2007), pp. 80-111 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/517545 . Accessed: 07/07/2013 13:58 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Modern History. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 169.229.32.136 on Sun, 7 Jul 2013 13:58:54 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Contemporary Issues in Historical Perspective “Down in Turkey, far away”: Human Rights, the Armenian Massacres, and Orientalism in Wilhelmine Germany* Margaret Lavinia Anderson University of California, Berkeley Famous in the annals of German drama is a scene known as the “Easter stroll,” in which the playwright takes leave, briefly, from his plot to depict a cross section of small-town humanity enjoying their holiday. -

John Raleigh Mott 1946 He Has Gone out Into the Whole World and Opened Hearts to the Idea of Peace, to Understanding, Love and Tolerance

John Raleigh Mott 1946 He has gone out into the whole world and opened hearts to the idea of peace, to understanding, love and tolerance. John Raleigh Mott won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1946. He shared the honor with Emily Balch. The Nobel Committee recognized his dedication to peace. He improved the quality of human life. The committee said he knew the fundamental issue. He opened hearts to tolerance and understanding. John Mott was born after Lincoln was assassinated. At 16 years, he enrolled in university. He became active in the Student Christian Association. He decided to become a Christian leader. He was president of the local Y.M.C.A. He graduated with honors. He worked for the Y.M.C.A. all his life. He was president of the international Y.M.C.A. for 11 years. John Mott became a leader in other • He was a missionary, organizations. He continued to author, speaker, “world spread the message of peace. In citizen” 1895, he started the World’s Student Christian Federation. He traveled • He was a Leader in the around the world. He visited Young Men’s Christian twenty-four nations. He worked for Association (Y.M.C.A.) the World’s Student Christian Federation. They believed in the • He was a Member of brotherhood and sisterhood of all special peace teams to people. They united all races, Russia and Mexico nationalities, and creeds. They stood against injustice, inequality, • He was Founder of the and violence. They thought there World’s Student Christian were other ways to solve problems. -

History of the Christian Flag

History of the Christian Flag The Christian Flag is a flag designed in the early 20th century to represent all of Christianity and Christendom, and has been most popular among Protestant churches in North America, Africa and Latin America. The flag has a white field, with a red Latin cross inside a blue canton. The shade of red on the cross symbolizes the blood that Jesus shed on Calvary. The blue represents the waters of baptism as well as the faithfulness of Jesus. The white represents Jesus' purity. In conventional vexillology, a white flag is linked to surrender, a reference to the Biblical description of Jesus' non-violence and surrender to God. The dimensions of the flag and canton have no official specifications. The Christian flag is not tied to any nation or denomination; however, non-Protestant branches of Christianity do not often fly it. According to the Prayer Foundation, the Christian flag is uncontrolled, independent, and universal. Its universality and free nature is meant to symbolize the nature of Christianity. According to Wikipedia and other online sources, the Christian flag dates back to an impromptu speech given by Charles C. Overton, a Congregational Sunday school superintendent in New York, on Sunday, September 26, 1897. The Union Sunday school that met at Brighton Chapel Coney Island had designated that day as Rally Day. The guest speaker for the Sunday school kick-off didn't show up, so Overton had to wing it. Spying an American flag near (or draped over) the podium (or piano), he started talking about flags and their symbolism. -

Johannes Lepsius: Theologian, Humanitarian Activist and Historian of Völkermord

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2011 Johannes Lepsius: Theologian, humanitarian activist and historian of Völkermord. An approach to a German biography (1858–1926) Kieser, H L Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-61176 Book Section Accepted Version Originally published at: Kieser, H L (2011). Johannes Lepsius: Theologian, humanitarian activist and historian of Völkermord. An approach to a German biography (1858–1926). In: Briskina-Müller, A; Drost-Abgarjan, A; Meissner, A. Logos im Dialogos : Auf der Suche nach der Orthodoxie. Berlin: Lit, 209-229. Johannes Lepsius: Theologian, Humanitarian Activist and Historian of Völkermord. An Approach to a German Biography (1858-1926) Hans-Lukas Kieser After having been almost forgotten for decades, the German pastor, author and activist Johannes Lepsius has in the last twenty years become a topic of heated public discussions in Germany and beyond. Among the recent bones of contention is the federally subsidized Lepsiushaus, that is the house of Johannes Lepsius in Potsdam, now transformed to a memorial and research center, and which is Professor Hermann Goltz's lifework. With good reason, Lepsius was and remains highly respected internationally as a humanitarian and a brave witness of truth with regard to the Armenian genocide. His commitment and his variegated life raise important questions. Can his intellectual and social biography offer new insights into a history which has all too clearly remained a site of contestation until the present day? What of his theological background and his transnational networks? What about the role of his patriotic bonds to Wilhelmine Germany? Writing in exile in Basel in 1937, a family friend, the art historian Werner Weisbach, described how the life of Lepsius was an inspiring example of truthfulness, philanthropy and patriotism. -

131825-Memory-Folder.Pdf

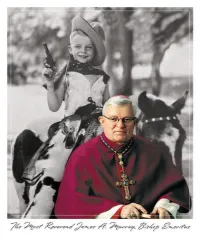

During the Great Depression in the mid-sized Michigan town of Jackson, James and Clare Murray welcomed their third son, James on July 5, 1932. His early years were spent playing baseball and running around with his two older brothers, Bill and Jack. He attended St. Mary Catholic Elementary school and was taught by the Sisters of Charity. Jim was naturally left-handed and was fond of retelling the story of the Sisters calling his mom to school concerned about this. She told them, “We know Jim’s a little off, but we like him that way.” And so he remained left-handed and was known throughout his life for his beautiful penmanship. As evidenced by his St. Mary’s High School yearbook (which he served as editor), Jim excelled both academically and also participated in many extracurricular activities including baseball, boxing, the Glee Club, chairman of the Prom Committee and, not surprisingly, was elected Senior Class President at St. Mary High School. During those days he recounted that he had ideas of becoming a priest, but also entertained thoughts of being a doctor or a lawyer. The calling to the Priesthood won out and Jim studied at Sacred Heart Seminary where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree and at St. John Seminary, Plymouth earning a Bachelor of Theology degree. He was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Lansing by Bishop Joseph H. Albers on June 7, 1958 at St. Mary Cathedral, Lansing. He celebrated his first Mass in his hometown of Jackson at St. Mary Parish and was assisted by long-time friend Fr. -

New Chaplain Strengthens Latin Mass Community

50¢ March 9, 2008 Volume 82, No. 10 www.diocesefwsb.org/TODAY Serving the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend TTODAYODAY’’SS CCATHOLICATHOLIC Springing forward New chaplain strengthens Daylight Saving Time begins Latin Mass community March 9; get to Mass on time Baptism dilemma BY DON CLEMMER Using wrong words FORT WAYNE — Father George Gabet discovered ruled not valid his love for the old Latin Mass years before his ordi- nation while attending it at Sacred Heart Parish in Fort Page 5 Wayne. Now he will be serving Sacred Heart, as well as Catholics in South Bend, through his new assign- ment as a chaplain of a community formed especially for Catholics who worship in the pre-Vatican II rite. This rite, called the 1962 Roman Missal, the Award winning Tridentine Rite and, more recently, the extraordinary teachers form of the Roman Missal, has received greater atten- tion since the July 2007 publication of Pope Benedict Theology teachers XVI’s motu proprio, “Summorum Pontificum,” allowed for greater use of it. cited for gifts To meet the needs of Catholics wishing to worship in this rite in the Diocese of Fort Wayne-South Bend, Page 10 Bishop John M. D’Arcy has established the St. Mother Theodore Guérin Community. This community, which came into effect March 1, will consist of parishioners at Sacred Heart in Fort Wayne and St. John the Baptist Vices and virtues in South Bend, two parishes that have offered the Tridentine rite Mass since 1990. Father George Gabet Envy and sloth explored will be the community’s chaplain.