Galvanic Corrosion Between Depleted Uranium and 40Cr Steel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

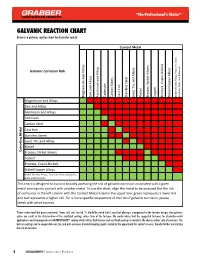

GALVANIC REACTION CHART Below Is a Galvanic Reaction Chart for Dissimilar Metals

GALVANIC REACTION CHART Below is a galvanic reaction chart for dissimilar metals. Contact Metal Silver, Silver, Galvanic Corrosion Risk Alloys Alloys Platinum Alloys Alloys, Titanium, and Alloys Steels Gold, and Iron Cast Stainless Steel Lead, Tin, and Magnesium and Zinc and Cadmium Carbon Nickel Brasses, Nickel-Silvers Copper Bronzes, Cupro-Nickels Nickel Copper Alloys Aluminum Graphite, Nickel-Chrome Magnesium and Alloys Zinc and Alloys Aluminum and Alloys Cadmium Carbon Steel Cast Iron Metal Stainless Steels Lead, Tin, and Alloys Nickel Corroding Brasses, Nickel-Silvers Copper Bronzes, Cupro-Nickels Nickel Copper Alloys Nickel-Chrome Alloys, Titanium, Silver, Graphite, Gold, and Platinum This chart is designed to assist in broadly assessing the risk of galvanic corrosion associated with a given metal coming into contact with another metal. To use the chart, align the metal to be assessed (for the risk of corrosion) in the left column with the Contact Metal listed in the upper row; green represents a lower risk and red represents a higher risk. For a more specific assessment of the risk of galvanic corrosion, please check with other sources. Please understand that green represents "lower risk" not "no risk." It should be noted that if sacrificial plating is incorporated in the fastener design, then galvanic action can result in the deterioration of the sacrificial coating, rather than of the fastener. We would advise that the suggested fasteners for dissimilar-metal applications would incorporate our GRABBERGARD® coating which utilizes both barrier and sacrificial coatings to minimize the chance and/or rate of corrosion. The barrier coating used to encapsulate our zinc and anti-corrosion chemical bonding agents minimize the opportunity for contact to occur, thereby further minimizing the risk of corrosion. -

Galvanic Corrosion

10 GALVANIC CORROSION X. G. ZHANG Teck Metals Ltd., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada A. Introduction graphite, are dispersed in a metal, or on a ship, where the B. Definition various components immersed in water are made of different C. Factors in galvanic corrosion metal alloys. In many cases, galvanic corrosion may result in D. Material factors quick deterioration of the metals but, in other cases, the D1. Effects of coupled materials galvanic corrosion of one metal may result in the corrosion D2. Effect of area protection of an attached metal, which is the basis of cathodic D3. Effect of surface condition protection by sacrificial anodes. E. Environmental factors Galvanic corrosion is an extensively investigated subject, E1. Effects of solution as shown in Table 10.1, and is qualitatively well understood E2. Atmospheric environments but, due to its highly complex nature, it has been difficult to E3. Natural waters deal with in a quantitative way until recently. The widespread F. Polarity reversal use of computers and the development of software have made G. Preventive measures great advances in understanding and predicting galvanic H. Beneficial effects of galvanic corrosion corrosion. I. Fundamental considerations I1. Electrode potential and Kirchhoff’s law I2. Analysis B. DEFINITION I3. Polarization and resistance I4. Potential and current distributions When two dissimilar conducting materials in electrical con- References tact with each other are exposed to an electrolyte, a current, called the galvanic current, flows from one to the other. Galvanic corrosion is that part of the corrosion that occurs at the anodic member of such a couple and is directly related to the galvanic current by Faraday’s law. -

Galvanic Corrosion Final

GALVANIC CORROSION by Stephen C. Dexter, Professor of Applied Science and Marine Biology, (302) 645-4261 Galvanic corrosion, often misnamed “electrolysis,” is one common form of corrosion in marine environments. It occurs Table 1 when two (or more) dissimilar metals are brought into electri- GALVANIC SERIES cal contact under water. When a galvanic couple forms, one of In Flowing Seawater the metals in the couple becomes the anode and corrodes faster than it would all by itself, while the other becomes the cathode Voltage Range of Alloy and corrodes slower than it would alone. Either (or both) metal Alloy vs. Reference Electrode* in the couple may or may not corrode by itself (themselves) in MagnesiumAnodic or -1.60 to -1.63 seawater. When contact with a dissimilar metal is made, how- Active End ever, the self-corrosion rates will change: corrosion of the Zinc -0.98 to -1.03 anode will accelerate; corrosion of the cathode will decelerate Aluminum Alloys -0.70 to -0.90 or even stop. We can use the seawater Galvanic Series, shown Cadmium -0.70 to -0.76 in Table 1, to predict which metal will become the anode and Cast Irons -0.60 to -0.72 how rapidly it will corrode. Steel -0.60 to -0.70 Aluminum Bronze -0.30 to -0.40 The seawater Galvanic Series is a list of metals and alloys Red Brass, Yellow Brass, ranked in order of their tendency to corrode in marine environ- Naval Brass -0.30 to -0.40 ments. If any two metals from the list are coupled together, the Copper -0.28 to -0.36 one closer to the anodic (or active) end of the series, the Lead-Tin Solder (50/50) -0.26 to -0.35 upper end in this case, will be the anode and thus will corrode Admiralty Brass -0.25 to -0.34 faster, while the one toward the cathodic (or noble) end will Manganese Bronze -0.25 to -0.33 corrode slower. -

Galvanic Corrosion Between Zinc and Carbon Steel Investigated by Local

Galvanic corrosion between zinc and carbon steel investigated by local electrochemical impedance spectroscopy Maixent Mouanga, Monique Puiggali, Bernard Tribollet, Vincent Vivier, Nadine Pébère, Olivier Devos To cite this version: Maixent Mouanga, Monique Puiggali, Bernard Tribollet, Vincent Vivier, Nadine Pébère, et al.. Gal- vanic corrosion between zinc and carbon steel investigated by local electrochemical impedance spec- troscopy. Electrochimica Acta, Elsevier, 2013, 88, pp.6-14. 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.10.002. hal- 01165531 HAL Id: hal-01165531 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01165531 Submitted on 19 Jun 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Open Archive TOULOUSE Archive Ouverte ( OATAO ) OATAO is an open access repository that collects the work of Toulouse researchers and makes it freely available over the web where possible. This is an author-deposited version published in : http://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/ Eprints ID : 14080 To link to this article : doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2012.10.002 URL : http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2012.10.002 To cite this version : Mouanga, Maixent and Puiggali, Monique and Tribollet, Bernard and Vivier, Vincent and Pébère, Nadine and Devos, Olivier Galvanic corrosion between zinc and carbon steel investigated by local electrochemical impedance spectroscopy . -

The Care of Historic Musical Instruments

The Care of Historic Musical Instruments Edited by Robert L. Barclay This publicatio11 lias bee11 produced by tile Museums & Galleries Commissio 11, the Ca11adia11 Co 11servatio11 IHstitute a11dthe IHtemati01 ml Commillee of Mu sical lllslmmelll Mu seums a11d Collectio11 s of the llltematiollal Cou 11 cil of Museums with fillallcial assista11ce from tile folm S. Colle11 Fou11da tio11. c .. -.HI I A ' b. u~t u t MUSEUMS & GALLERI ES Co..:u •\·.. uo~ CO:.IliiiSSION '''"".. " CIMCIM Edinburgh 1997 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 1997, as represented by the Minister of the Department of Canadian Heritage acting through the Canadian Conservation Institute. Table of Contents ©Museums & Galleries Commission. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, by photocopying, recording or otherwise, for purposes of resale, without the prior Preface written permission of the copyright holders. All requests for permission must be directed to one of the following addresses: 1. Ethics and the Use of Instruments 1 Codes of Ethics and Standards 2 North America: All other countries and territories: Guidelines 3 Canadian Conservation Institute Museums & Galleries Commission Playability and "Soundability" 6 1030 Innes Road 16 Queen Anne's Gate Conclusion 7 Ottawa, Ontario KIA OMS London SW IH 9AA CANADA UNITED KINGDOM 2. Instruments in Their Environment 9 Conservation Assessment 9 Available for purchase from: Strategies for Environmental Control 11 Extension Services, Canadian Conservation Institute 3. General Care of Musical Instrument Collections 19 .Support for Display and Storage 19 Storage 22 Handling 23 Travel 24 Cataloguing in Publication Data Strategies to Counter Biological Attack 25 Main entry under title : 4. -

Galvanic Corrosion Dealloying Corrosion Velocity Phenomena

Galvanic Corrosion Dealloying Corrosion Velocity Phenomena Note: While this course does not contain proprietary BWRVIP or MRP information, per se, it does contain open literature information that was used in the creation of BWRVIP or MRP documents or BWRVIP or MRP information that was subsequently made non-proprietary via publication, etc. Corrosion and Corrosion Control in LWRs © 2011 by SIA, Inc. All rights reserved. Galvanic, Dealloying and Fluid Velocity Corrosion Learning Objectives • Understand the mechanism of galvanic corrosion ♦ Does “galvanic corrosion” always involve different metals? ♦ Is corrosion essentiallyyyg always galvanic corrosion? ♦ Cathodic protection • Identify dealloying corrosion • Understand the mechanism of the effects of fluid flow on corrosion ♦ Flow-accelerated corrosion (FAC) Corrosion and Corrosion Control in LWRs PRS-11-037 D BMG/ 2 © 2011 by SIA, Inc.. All rights reserved. Specific Forms of Corrosion 1. General or uniform corrosion 2. Galvanic corrosion 3. De-alloying corrosion Macro 4. Velocity phenomena - erosion corrosion, Localized Corrosion cavitation, impingement, fretting and FAC 5. Crevice corrosion 6. Pitting corrosion 7. Intergranular corrosion Micro Localized 8. Corrosion fatigue Corrosion 9. Stress corrosion cracking Microbiological activity can affect all of the above Corrosion and Corrosion Control in LWRs PRS-11-037 D BMG/ 3 © 2011 by SIA, Inc.. All rights reserved. Galvanic Corrosion Corrosion and Corrosion Control in LWRs © 2011 by SIA, Inc. All rights reserved. Galvanic Corrosion • History • Mechanism • LWR Case Study Examples ♦ Condensers ♦ Sensitization of stainless steel Corrosion and Corrosion Control in LWRs PRS-11-037 D BMG/ 5 © 2011 by SIA, Inc.. All rights reserved. Galvanic Corrosion • If you could fabricate a component from only one alloy, galvanic corrosion would not be a problem. -

Enghandbook.Pdf

785.392.3017 FAX 785.392.2845 Box 232, Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expy Minneapolis, KS 67467 ENGINEERING HANDBOOK TECHNICAL INFORMATION STEELMAKING Basic descriptions of making carbon, alloy, stainless, and tool steel p. 4. METALS & ALLOYS Carbon grades, types, and numbering systems; glossary p. 13. Identification factors and composition standards p. 27. CHEMICAL CONTENT This document and the information contained herein is not Quenching, hardening, and other thermal modifications p. 30. HEAT TREATMENT a design standard, design guide or otherwise, but is here TESTING THE HARDNESS OF METALS Types and comparisons; glossary p. 34. solely for the convenience of our customers. For more Comparisons of ductility, stresses; glossary p.41. design assistance MECHANICAL PROPERTIES OF METAL contact our plant or consult the Machinery G.L. Huyett’s distinct capabilities; glossary p. 53. Handbook, published MANUFACTURING PROCESSES by Industrial Press Inc., New York. COATING, PLATING & THE COLORING OF METALS Finishes p. 81. CONVERSION CHARTS Imperial and metric p. 84. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Steelmaking 4 Metals and Alloys 13 Designations for Chemical Content 27 Designations for Heat Treatment 30 Testing the Hardness of Metals 34 Mechanical Properties of Metal 41 Manufacturing Processes 53 Manufacturing Glossary 57 Conversion Coating, Plating, and the Coloring of Metals 81 Conversion Charts 84 Links and Related Sites 89 Index 90 Box 232 • Exit 49 G.L. Huyett Expressway • Minneapolis, Kansas 67467 785-392-3017 • Fax 785-392-2845 • [email protected] • www.huyett.com INTRODUCTION & ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This document was created based on research and experience of Huyett staff. Invaluable technical information, including statistical data contained in the tables, is from the 26th Edition Machinery Handbook, copyrighted and published in 2000 by Industrial Press, Inc. -

Corrosion Information Galvanic Action

R CORROSION Information C Galvanic ACTION Galvanic CORROSION - compatible metals charts To minimize galvanic corrosion, fasteners should be considered based on their material compatibility with the substrates. Determine the materials being fastened and choose a fastener material that is close in proximity on the chart. The closer together the material are on the chart the less galvanic action will occur. Metals listed on the top of the chart (anotic) will corrode faster than the metals on the bottom of the chart (cathodic). Contact a corrosion specialist to determine the best material for your application. Fastener Material Selection Based on the Galvanic Series of Metals Revised by TFC: 0315JS Table developed using information supplied by AISI Committee of Stainless Steel Producers. Key A. The corrosion of the base metal is not increased by the fastener. B. The corrosion of the base metal is slightly increased by the fastener. C. The corrosion of the base metal may be considerably increased by the fastener material. D. The plating on the fastener is rapidly consumed. E. The corrosion of the fastener is increased by the base metal. FASTENER MATERIAL STEEL STAINLESS STEEL STAINLESS STEEL Zinc Plated Type 410 Type 302, 304, 316 ALUMINUM Zinc | Galvanized | ZN/Al A C C B Coated Steel Aluminum A 1Not Recommended B A Steel / Cast Iron A,D C B A Brass, Copper, Bronze A,D,E A B A,E Stainless Steel BASE METAL A,D,E A A A,E 300 Series Footnotes 1. Because aluminum can expand a large distance, the high hardness of 410 SS case harden screws may lead to screw to failure due to lack of ductility or stress corrosion cracking. -

How Cras Now Support the Statue of Liberty

Architecture How CRAs now support the Statue of Liberty Built in 1886, the copper-clad Statue of Liberty has required quite some maintenance and renovation to keep it in pristine condition. In 1986, for example, engineers decided to replace rusty iron components with advanced materials such as Ferralium and 316L. By David Sear Image: Wikimedia Commons A gift of friendship from the people of designed the internal framework that At the heart of the Statue of Liberty became a national cause in the USA France to the United States, "The Statue keeps the Statue of Liberty standing. Eiffel therefore placed a sturdy iron and also France, with many companies of Liberty Enlightening the World" is As visitors to the Statue of Liberty will tower, comprising four legs. This tower donating both materials and services to recognized the world over as a uni- testify, it is in fact nothing more than a is surrounded by a secondary array of the project. versal symbol of freedom and democ- hollow shell, formed by 310 skillfully con- supporting iron beams and bars. These Engineers tasked with working out racy. Since its dedication in 1886 it has toured copper plates riveted together at connect the central tower to so-called how best to repair the Statue of Liberty become an iconic structure instantly rec- the edges. Eifel realised that this copper ribs, fl at strips of iron which have been decided that the ‘puddled iron’ in the ognised by people from all continents. shell, weighing more than 80 tonnes, bent into shape to follow the exact cur- internal superstructure needed replac- When fi rst built the Statue of Liberty would be unable to support its own vature of each and every copper plate. -

Corrosion Basics

CORROSION BASICS (from Swain (1996) and Schultz (1997)) What is corrosion? • Webster’s Dictionary - corrode (v.) To eat away or be eaten away gradually, especially by chemical action. • NACE Corrosion Basics - corrosion may be defined as the deterioration of a material (usually a metal) because of a reaction with the environment. Why do metals corrode? Most metals are found in nature as ores. The manufacturing process of converting these ores into metals involves the input of energy. During the corrosion reaction the energy added in manufacturing is released, and the metal is returned to its oxide state. Metal Ore reduction (add electrons)→ Metal oxidation (strip electrons)→ Corrosion Products In the marine environment, the corrosion process generally takes place in aqueous solutions and is therefore electrochemical in nature. Corrosion consequences Economic - corrosion results in the loss of $8 - $126 billion annually in the U.S. alone. This impact is primarily the result of: 1. Downtime 2. Product Loss 3. Efficiency Loss 4. Contamination 5. Overdesign Safety / Loss of Life Corrosion can lead to catastrophic system failures which endanger human life and health. Examples include a 1967 bridge collapse in West Virginia which killed 46. The collapse was attributed to stress corrosion cracking (SCC). In another example, the fuselage of an airliner in Hawaii ripped open due to the combined action of stress and atmospheric corrosion. Corrosion cell Corrosion occurs due to the formation of electrochemical cells. In order for the corrosion reaction to occur five things are necessary. If any of these factors are eliminated, galvanic corrosion will not occur. THIS IS THE KEY TO CORROSION CONTROL! The necessary factors for corrosion to proceed are: 1. -

Microgalvanic Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Ag Active Braze Alloys Investigated with SKPFM

metals Article Microgalvanic Corrosion Behavior of Cu-Ag Active Braze Alloys Investigated with SKPFM Armen Kvryan, Kari Livingston, Corey M. Efaw, Kyle Knori, Brian J. Jaques, Paul H. Davis, Darryl P. Butt and Michael F. Hurley * Department of Materials Science and Engineering, College of Engineering, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725-2090, USA; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (K.L.); [email protected] (C.M.E.); [email protected] (K.K.); [email protected] (B.J.J.); [email protected] (P.H.D.); [email protected] (D.P.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-208-426-4075 Academic Editors: Vineet V. Joshi and Alan Meier Received: 3 February 2016; Accepted: 6 April 2016; Published: 19 April 2016 Abstract: The nature of microgalvanic couple driven corrosion of brazed joints was investigated. 316L stainless steel samples were joined using Cu-Ag-Ti and Cu-Ag-In-Ti braze alloys. Phase and elemental composition across each braze and parent metal interface was characterized and scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy (SKPFM) was used to map the Volta potential differences. Co-localization of SKPFM with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) measurements enabled spatially resolved correlation of potential differences with composition and subsequent galvanic corrosion behavior. Following exposure to the aggressive solution, corrosion damage morphology was characterized to determine the mode of attack and likely initiation areas. When exposed to 0.6 M NaCl, corrosion occurred at the braze-316L interface preceded by preferential dissolution of the Cu-rich phase within the braze alloy. Braze corrosion was driven by galvanic couples between the braze alloys and stainless steel as well as between different phases within the braze microstructure. -

Galvanic Corrosion Prevention Guide for Water Cooling Systems

WATER COOLED DEVICES Galvanic Corrosion Prevention Guide for Water Cooling Systems November 2017 | White Paper Water Created by Cooled Helen E. Kane, Advanced Energy Industries, Inc. Devices Abstract Table of Contents This report details best practices for reducing the risk of galvanic corrosion in water cooling system designs. Galvanic Summary and Background 2 corrosion will manifest if the following conditions exist: Research Findings 2 Best Practices Recommendations 5 1 Electrically dissimilar metals in contact (or both in References 7 contact with the same water) 2 Electrolyte present (could be as simple as condensation) Time is another critical factor. The mean time to failure can be short or long, depending on the combination of conditions 1 and 2. This report provides the galvanic series for general metals and compatibility. In addition, it lists preventative measures to avoid issues in open loop cooling water systems. 2 GALVANIC CORROSION PREVENTION GUIDE FOR WATER COOLING SYSTEMS Summary and Background This report details best practices for reducing the risk of galvanic corrosion in mechani- cal and electro-mechanical cooling system designs. Galvanic corrosion, sometimes called bimetallic or dissimilar metal corrosion, is when one metal in a system experiences corrosion due to an electro-chemical reaction with a different metal and an electrolyte in the same system. Galvanic corrosion has been experienced in designs with dissimilar metals used in Advanced Energy products that use water cooling. Because conditions that promote gal- vanic reactions can exist inside Advanced Energy units due to the environment and running conditions, some simple best practices will help reduce the risk of galvanic corrosion failure.