Caught in the Middle: the Impact of Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gurriculum Vitae

حوكمةتا هةريَما كوردستانىَ – عرياق حكومت أقليم كودستان – العراق وزارة التعليم العالي والبحث العلمي وةزراتا خوندنا باﻻ وتوذينيَت زانستى رئاست جامعت بولينكنيك دهوك سةوركاتيا زانلويا ثوليتةكنيلا دهوك Kurdistan Regional Government-Iraq Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Duhok Polytechnic University Curriculum Vitae University Address: 61 Zahko Road, 1006 Mazi Qt., Duhok , Kurdistan -Iraq A / Personal data Name: Mohammed Haydar Mosa Date of Birth: 1/1/1971 Place of Birth: Mosul City \ lraq Marital Status: Married Mother Tongue: Kurdish Other Language: Kurdish, English and Arabic Degree: M.Sc. Nursing from Nursing College/ Mosul University\ Iraq 2005 B\Educational University University Collage Degree Date (Year) Specialty Mosul Mosul Technical Technical Diploma 199 - 1993 Anesthesia Institute\Iraq Institute\Iraq Mosul College of Nursing B.SC 1994 - 1998 University Nursing Science Mosul College of Pediatric M.SC 2003 - 2005 University Nursing health nursing C\Training and education: Name ,Place , Country Type Years attended Academic degree obtained From To Tumor workshop \ Tumor 21/9/1996 - 29/9/1996 Training Mosul \Iraq nursing Second conference tumor Tumor 22/9/1996 - 24/9/1996 Training Of Mosul \Iraq Course & methods to teach public health\ Community 12 October 2004 Training Community health health nursing - 15 October 2004 nursing \ Duhok \ Iraq Cardiac catheterization Cardiac \ Azadi teaching 2007 Training catheterization hospital \Duhok\ Iraq Methods of education Methods of \Duhok Technical 4/7/2009 - 18/7/2006 education institute \Iraq Evaluation of health Environmental states At health Institutions In 7th scientific conference conference 27-28 September 2010 Iraq. Mosul proceedings university\Nursing collage The role of Scientific research in Developing 10th National scientific of public health . -

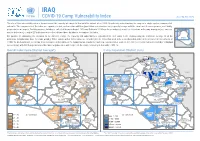

COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020

IRAQ COVID-19 Camp Vulnerability Index As of 04 May 2020 The aim of this vulnerability index is to understand the capacity of camps to deal with the impact of a COVID-19 outbreak, understanding the camp as a single system composed of sub-units. The components of the index are: exposure to risk, system vulnerabilities (population and infrastructure), capacity to cope with the event and its consequences, and finally, preparedness measures. For this purpose, databases collected between August 2019 and February 2020 have been analysed, as well as interviews with camp managers (see sources next to indicators), a total of 27 indicators were selected from those databases to compose the index. For purpose of comparing the situation on the different camps, the capacity and vulnerability is calculated for each camp in the country using the arithmetic average of all the IRAQ indicators (all indicators have the same weight). Those camps with a higher value are considered to be those that need to be strengthened in order to be prepared for an outbreak of COVID-19. Each indicator, according to its relevance and relation to the humanitarian standards, has been evaluated on a scale of 0 to 100 (see list of indicators and their individual assessment), with 100 being considered the most negative value with respect to the camp's capacity to deal with COVID-19. Overall Index Score (District Average*) Camp Population (District Sum) TURKEY TURKEY Zakho Zakho Al-Amadiya 46,362 Al-Amadiya 32 26 3,205 DUHOK Sumail DUHOK Sumail Al-Shikhan 83,965 Al-Shikhan Aqra -

Irak : Situation Sécuritaire Dans Le District De Sinjar

Irak : situation sécuritaire dans le district de Sinjar Recherche rapide de l’analyse-pays Berne, 28 novembre 2018 Conformément aux standards COI, l’OSAR fonde ses recherches sur des sources accessibles publiquement. Lorsque les informations obtenues dans le temps imparti sont insuffisantes, elle fait appel à des expert -e-s. L’OSAR documente ses sources de manière transparente et traçable, mais peut toutefois décider de les anony- miser, afin de garantir la protection de ses contacts. Impressum Editeur Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés (OSAR) Case postale, 3001 Berne Tél. 031 370 75 75 Fax 031 370 75 00 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.osar.ch CCP dons: 10-10000-5 Versions français, allemand COPYRIGHT © 2018 Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés (OSAR), Berne Copies et impressions autorisées sous réserve de la mention de la source 1 Introduction Le présent document a été rédigé par l’analyse-pays de l’Organisation suisse d’aide aux réfugiés (OSAR) à la suite d’une demande qui lui a été adressée. Il se penche sur les ques- tions suivantes: Quelle est la situation sécuritaire dans le district de Sinjar (province de Ninawa) ? L’ « État islamique » (EI) autoproclamé /Daesh est-il encore présent ou représente-il encore une menace dans ce district ? 1. Quels sont les principaux obstacles au retour des personnes déplacées et à la recons- truction dans le district de Sinjar ? 2. Est-il concevable qu'un enfant mineur irakien d'origine kurde, qui a passé plusieurs mois dans un camp de l’EI/Daesh dans le district de Sinjar, puisse à son retour subir des me- sures de représailles de la part de la population locale ? Pour répondre à ces questions, l’analyse-pays de l’OSAR s’est fondée sur des sources ac- cessibles publiquement et disponibles dans les délais impartis (recherche rapide) ainsi que sur des renseignements d’expert-e-s. -

The Kurds; History and Culture

Western Kurdistan Association publications Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture Jemal Nebez THE KURDS History and Kulture Presentation held in German on the 19th September 1997 in the Kurdish Community- House in Berlin, Germany First published in German in 1997 by: The Kurdish Community House in Berlin, Germany First publication in English, including a Bio-Bibliography of Jemal Nebez, by: WKA Publications - London 2004 Translated into English by: Hanne Kuchler Preface by: Dr. Hasan Mohamed Ali Director of the Board of the Kurdish Community House in Berlin, Germany 1 Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture 2 Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture PREFACE On the occasion of the inauguration of the Kurdish community-house in Berlin, Germany in September 1997, the well-known Kurdologist Dr. Jemal Nebez held a warmly received speech under the title: The Kurds – their history and culture. This speech was not only of great importance because of its contents and coverage, but also because it was based on precise data and historic scientific evidence. In his speech Dr. Nebez covered various subjects, e.g. pre- Christian ancient history and the mythology of the Kurds, the cultural height and depth of the Kurdish people in the shadow of the numerous expeditions by alien peoples through Kurdistan, the astounding variety of religions in Kurdistan, with special stress on syncretism as the most striking feature of the Kurdish religious culture, delineating syncretism as inherently different from mixed religions. As an analytically thinking scientist (physicist) the speaker did not get stuck in the past, nor was his speech 3 Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture an archaeological presentation, but an Archigenesis, which in fluent transition reaches from past epochs to the present situation of the Kurdish people. -

The Birth of Al-Wahabi Movement and Its Historical Roots

The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Original Document Information ~o·c·u·m·e·n~tI!i#~:I~S=!!G~Q~-2!110~0~3~-0~0~0~4'!i66~5~9~"""5!Ii!IlI on: nglis Title: Correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General Military Intelligence irectorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of AI-Wahhabiyyah ovement and its Historical Roots" age: ARABIC otal Pages: 53 nclusive Pages: 52 versized Pages: PAPER ORIGINAL IRAQI FREEDOM e: ountry Of Origin: IRAQ ors Classification: SECRET Translation Information Translation # Classification Status Translating Agency ARTIAL SGQ-2003-00046659-HT DIA OMPLETED GQ-2003-00046659-HT FULL COMPLETED VTC TC Linked Documents I Document 2003-00046659 ISGQ-~2~00~3~-0~0~04~6~6~5~9-'7':H=T~(M~UI:7::ti""=-p:-a"""::rt~)-----------~II • cmpc-m/ISGQ-2003-00046659-HT.pdf • cmpc-mIlSGQ-2003-00046659.pdf GQ-2003-00046659-HT-NVTC ·on Status: NOT AVAILABLE lation Status: NOT AVAILABLE Related Document Numbers Document Number Type Document Number y Number -2003-00046659 161 The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Keyword Categories Biographic Information arne: AL- 'AMIRI, SA'IO MAHMUO NAJM Other Attribute: MILITARY RANK: Colonel Other Attribute: ORGANIZATION: General Military Intelligence Directorate Photograph Available Sex: Male Document Remarks These 53 pages contain correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General i1itary Intelligence Directorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of I-Wahhabiyyah Movement and its Historical Roots". -

Iraq: Opposition to the Government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Opposition to the government in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 2.0 June 2021 Preface Purpose This note provides country of origin information (COI) and analysis of COI for use by Home Office decision makers handling particular types of protection and human rights claims (as set out in the Introduction section). It is not intended to be an exhaustive survey of a particular subject or theme. It is split into two main sections: (1) analysis and assessment of COI and other evidence; and (2) COI. These are explained in more detail below. Assessment This section analyses the evidence relevant to this note – i.e. the COI section; refugee/human rights laws and policies; and applicable caselaw – by describing this and its inter-relationships, and provides an assessment of, in general, whether one or more of the following applies: • A person is reasonably likely to face a real risk of persecution or serious harm • The general humanitarian situation is so severe as to breach Article 15(b) of European Council Directive 2004/83/EC (the Qualification Directive) / Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iii) of the Immigration Rules • The security situation presents a real risk to a civilian’s life or person such that it would breach Article 15(c) of the Qualification Directive as transposed in paragraph 339C and 339CA(iv) of the Immigration Rules • A person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies) • A person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory • A claim is likely to justify granting asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave, and • If a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. -

آشور القديمة Imperialist Networks

Present Pasts, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2010, 142-168, doi:10.5334/pp.30 شبكات اﻻمبريالية : آشور القديمة :Imperialist Networks والوﻻيات المتحدة Ancient Assyria and the United States راينهارد بيرنبك REINHARD BERNBECK آجامعة برلني الحرة وجامعة بنغهامتون Freie Universität Berlin and Binghamton University على مدى العقد الماضي, قام العديد من المؤرخين والمحللين السياسيين Over the last decade many historians and بتسليط الضوء على أوج��ه التشابه بين اﻻمبراطوريات الرومانية political analysts have sought to highlight واﻷمريكية. وتعرض هذه الورقة بديﻻ لهذه المعادﻻت من خﻻل مقارنة -similarities between the American and Ro ﻷمريكا واﻹمبراطورية اﻵشورية ، على أساس اختﻻفي معهم بأن لديهم -man Empires. This paper presents an alter التشابه الهيكلي ,ﻻ تشاركهم به روما. native to these equations by comparing the American and the Assyrian empire, based on my contention that they have structural similarities not shared by Rome. Introduction “Not since Rome has one nation loomed so large above the others”. With this sentence, Jo- seph Nye opens his book The Paradox of American Power (2002: 1). After the end of the cold war, and especially since 9/11, the notion of an “American empire” and the comparison with Rome as the sole precursor of the U.S. empire have become a mainstay of historians and political commentators alike (e.g. Kagan, 2002; Golub, 2002). Rome also underwent a transformation from republic to an imperial golden age, and reference is made to opinion leaders such as Cato, who said of Rome’s enemies: “Let them hate us as long as they fear us.” This sentiment is echoed by Charles Krauthammer (2001) who asserts that America “is the dominant power in the world, more than any since Rome. -

Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq

HUMAN RIGHTS UNAMI Office of the United Nations United Nations Assistance Mission High Commissioner for for Iraq – Human Rights Office Human Rights Report on the Protection of Civilians in the Armed Conflict in Iraq: 11 December 2014 – 30 April 2015 “The United Nations has serious concerns about the thousands of civilians, including women and children, who remain captive by ISIL or remain in areas under the control of ISIL or where armed conflict is taking place. I am particularly concerned about the toll that acts of terrorism continue to take on ordinary Iraqi people. Iraq, and the international community must do more to ensure that the victims of these violations are given appropriate care and protection - and that any individual who has perpetrated crimes or violations is held accountable according to law.” − Mr. Ján Kubiš Special Representative of the United Nations Secretary-General in Iraq, 12 June 2015, Baghdad “Civilians continue to be the primary victims of the ongoing armed conflict in Iraq - and are being subjected to human rights violations and abuses on a daily basis, particularly at the hands of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Ensuring accountability for these crimes and violations will be paramount if the Government is to ensure justice for the victims and is to restore trust between communities. It is also important to send a clear message that crimes such as these will not go unpunished’’ - Mr. Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 12 June 2015, Geneva Contents Summary ...................................................................................................................................... i Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology .............................................................................................................................. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Kirkuk and Its Arabization: Historical Background and Ongoing Issues In

Abstract The Arabization of the Kurdistan region in Iraq Since the establishment of the Iraqi state, the ruling Arab regimes forcibly displaced native Kurds and repopulated the area with Arab tribes. The change of demography,known as “Arabization,” existed in both Kurdish majority agriculture and urban lands. These policies were part of a larger Iraqi campaign to erase the Kurdish identity, occupy Kurdistan, and control its wealth. The Iraqi government’s campaign against the Kurds amounted to genocide and eventually destroyed Kurdish communities and the social fabric of Kurdistan. The areas affected by the Arabization stretch from eastern to northwestern Iraq , incorporating major cities,towns, and hundreds of villages. After the fall of Saddam Hussien’s dictatorship, these areas became referred to as “Disputed Territories'' in Iraq’s newly adopted constitution of 2005. Article 140 of Iraq’s constitution called for the normalization of the “Disputed Territories,” which was never implemented by the federal government of Iraq. 1 www.dckurd.org Kirkuk province, Khanagin city of Diyala province, Tuz Khurmatu District of Saladin Province, and Shingal (Sinjar) in Nineveh province are the main areas that continue to suffer from Arabization policies implemented in 1975. KIRKUK A key feature of Kirkuk is its diversity – Kurds, Arabs, Turkmens, Shiites, Sunnis, and Christians (Chaldeans and Assyrians) all co-exist in Kirkuk, and the province is even home to a small Armenian Christian population. GEOGRAPHY The province of Kirkuk has a population of more than 1.4 million, the overwhelming majority of whom live in Kirkuk city. Kirkuk city is 160 miles north of Baghdad and just 60 miles from Erbil, the capital of the Iraqi Kurdistan region. -

Next Steps in Syria

Next Steps in Syria BY JUDITH S. YAPHE early three years since the start of the Syrian civil war, no clear winner is in sight. Assassinations and defections of civilian and military loyalists close to President Bashar Nal-Assad, rebel success in parts of Aleppo and other key towns, and the spread of vio- lence to Damascus itself suggest that the regime is losing ground to its opposition. The tenacity of government forces in retaking territory lost to rebel factions, such as the key town of Qusayr, and attacks on Turkish and Lebanese military targets indicate, however, that the regime can win because of superior military equipment, especially airpower and missiles, and help from Iran and Hizballah. No one is prepared to confidently predict when the regime will collapse or if its oppo- nents can win. At this point several assessments seem clear: ■■ The Syrian opposition will continue to reject any compromise that keeps Assad in power and imposes a transitional government that includes loyalists of the current Baathist regime. While a compromise could ensure continuity of government and a degree of institutional sta- bility, it will almost certainly lead to protracted unrest and reprisals, especially if regime appoin- tees and loyalists remain in control of the police and internal security services. ■■ How Assad goes matters. He could be removed by coup, assassination, or an arranged exile. Whether by external or internal means, building a compromise transitional government after Assad will be complicated by three factors: disarray in the Syrian opposition, disagreement among United Nations (UN) Security Council members, and an intransigent sitting govern- ment. -

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict

The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya About MERI The Middle East Research Institute engages in policy issues contributing to the process of state building and democratisation in the Middle East. Through independent analysis and policy debates, our research aims to promote and develop good governance, human rights, rule of law and social and economic prosperity in the region. It was established in 2014 as an independent, not-for-profit organisation based in Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Middle East Research Institute 1186 Dream City Erbil, Kurdistan Region of Iraq T: +964 (0)662649690 E: [email protected] www.meri-k.org NGO registration number. K843 © Middle East Research Institute, 2017 The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of MERI, the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publisher. The Yazidis Perceptions of Reconciliation and Conflict MERI Policy Paper Dave van Zoonen Khogir Wirya October 2017 1 Contents 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................4 2. “Reconciliation” after genocide .........................................................................................................5