To Appear in Kurdish Studies Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kurds; History and Culture

Western Kurdistan Association publications Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture Jemal Nebez THE KURDS History and Kulture Presentation held in German on the 19th September 1997 in the Kurdish Community- House in Berlin, Germany First published in German in 1997 by: The Kurdish Community House in Berlin, Germany First publication in English, including a Bio-Bibliography of Jemal Nebez, by: WKA Publications - London 2004 Translated into English by: Hanne Kuchler Preface by: Dr. Hasan Mohamed Ali Director of the Board of the Kurdish Community House in Berlin, Germany 1 Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture 2 Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture PREFACE On the occasion of the inauguration of the Kurdish community-house in Berlin, Germany in September 1997, the well-known Kurdologist Dr. Jemal Nebez held a warmly received speech under the title: The Kurds – their history and culture. This speech was not only of great importance because of its contents and coverage, but also because it was based on precise data and historic scientific evidence. In his speech Dr. Nebez covered various subjects, e.g. pre- Christian ancient history and the mythology of the Kurds, the cultural height and depth of the Kurdish people in the shadow of the numerous expeditions by alien peoples through Kurdistan, the astounding variety of religions in Kurdistan, with special stress on syncretism as the most striking feature of the Kurdish religious culture, delineating syncretism as inherently different from mixed religions. As an analytically thinking scientist (physicist) the speaker did not get stuck in the past, nor was his speech 3 Jemal Nebez The Kurds; History and Culture an archaeological presentation, but an Archigenesis, which in fluent transition reaches from past epochs to the present situation of the Kurdish people. -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

História Concisa Das Linhagens De DNA Mitocondrial De Uma População De Judeus Curdos Através Da Análise Da Sua Região Controlo

História concisa das linhagens de DNA mitocondrial de uma população de Judeus Curdos através da análise da sua Região Controlo Tese submetida à UNIVERSIDADE DA MADEIRA com vista para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Bioquímica Aplicada Catarina Jeppesen Cruz Trabalho efetuado sob orientação de: Professor Doutor António Manuel Dias Brehm FUNCHAL - PORTUGAL 1 2 “If you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you do you have to keep moving forward.” Martin Luther King, Jr. 3 4 Agradecimentos A elaboração desta tese não seria possível sem o apoio e orientação de várias pessoas, que ainda contribuíram para o meu desenvolvimento pessoal e académico. Em primeiro lugar, gostaria de especialmente agradecer ao meu orientador, Professor Doutor António Brehm, pela oportunidade de efetuar o trabalho de investigação no Laboratório de Genética Humana. Agradeço também pelo seu apoio, experiência e orientação durante todo este processo e para a conclusão do projeto. Quero agradecer também a todos os membros do Laboratório pela ajuda, apoio e carinho que demonstraram durante todo este processo. Quero agradecer em especial à Sara Gomes por todo o apoio e orientação que me dedicou durante todo o trabalho de investigação e para a conclusão da dissertação. Quero ainda agradecer à Doutora Alexandra Rosa por todo o apoio que me deu para a compreensão da parte do desenho e tratamento das árvores filogenéticas, e à Professora Manuela Gouveia pela disponibilidade do seu aparelho de PCR. Por fim, quero agradecer à Ana Freitas e à Priscilla Figueira pela amizade e apoio durante todo o curso, e à minha família por todo o apoio e amor incondicional. -

The Political Integration of the Kurds in Turkey

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1979 The political integration of the Kurds in Turkey Kathleen Palmer Ertur Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ertur, Kathleen Palmer, "The political integration of the Kurds in Turkey" (1979). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 2890. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.2885 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. l . 1 · AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF ·Kathleen Palmer Ertur for the Master of Arts in Political Science presented February 20, 1979· I I I Title: The Political Integration of the Kurds in Turkey. 1 · I APPROVED EY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: ~ Frederick Robert Hunter I. The purpose of this thesis is to illustrate the situation of the Kurdish minority in Turkey within the theoretical parameters of political integration. The.problem: are the Kurds in Turkey politically integrated? Within the definition of political develop- ment generally, and of political integration specifically, are found problem areas inherent to a modernizing polity. These problem areas of identity, legitimacy, penetration, participatio~ and distribution are the basis of analysis in determining the extent of political integration ·for the Kurds in Turkey. When .thes_e five problem areas are adequate~y dealt with in order to achieve the goals of equality, capacity and differentiation, political integration is achieved. -

Kurdistan, Kurdish Nationalism and International Society

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science Maps into Nations: Kurdistan, Kurdish Nationalism and International Society by Zeynep N. Kaya A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, June 2012. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 77,786 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by Matthew Whiting. 2 Anneme, Babama, Kardeşime 3 Abstract This thesis explores how Kurdish nationalists generate sympathy and support for their ethnically-defined claims to territory and self-determination in international society and among would-be nationals. It combines conceptual and theoretical insights from the field of IR and studies on nationalism, and focuses on national identity, sub-state groups and international norms. -

Language Policy in Turkey and Its Effect on the Kurdish Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2015 Language Policy in Turkey and Its Effect on the Kurdish Language Sevda Arslan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Arslan, Sevda, "Language Policy in Turkey and Its Effect on the Kurdish Language" (2015). Master's Theses. 620. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/620 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LANGUAGE POLICY IN TURKEY AND ITS EFFECT ON THE KURDISH LANGUAGE by Sevda Arslan A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Political Science Western Michigan University August 2015 Thesis Committee: Emily Hauptmann, Ph.D., Chair Kristina Wirtz, Ph.D. Mahendra Lawoti, Ph.D. LANGUAGE POLICY IN TURKEY AND ITS EFFECT ON THE KURDISH LANGUAGE Sevda Arslan, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2015 For many decades the Kurdish language was ignored and banned from public use and Turkish became the lingua franca for all citizens to speak. This way, the Turkish state sought to create a nation-state based on one language and attempted to eliminate the use of other languages, particularly Kurdish, through severe regulations and prohibitions. -

A Day in the Life of a Kurdish Kid a Smithsonian Folkways Lesson

A Day in the Life of a Kurdish Kid A Smithsonian Folkways Lesson Designed by: Jay Sand “All Around This World,” a world music program for small children and their families Summary: The lesson will introduce children and their teachers to the Kurdish people and their history and culture by leading them on a Kurdish experience full of singing and dancing. Suggested Grade Levels: K-2 Country: Iraq, Iran, Syria, Turkey Region: “Kurdistan” Culture Group: Kurdish Genre: Work songs, love songs, tribal dance Instruments: voice, hand claps, oud and doumbek introduced in video Language: Kurdish Co-Curricular Areas: History, Political Science/International Studies, Current Events National Standards: (1, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9) Prerequisites: For children: No prerequisites For teachers: enthusiasm, energy, curiosity about the world, confidence to sing, dance and create, willingness to be a little silly (the children already have all this) Objectives Learn very basic concepts about Kurdish history and Kurdish rural culture (National Standard #9 ) Sing Kurdish songs using arrangements reinterpreted with English lyrics (National Standard #1) Dance in the style of a Kurdish folk tradition (National Standard #8) “Compose”/improvise lyrics to songs in the style of Kurdish work songs (National Standard #3) Listen to Kurdish folk music and Middle Eastern oud music (National Standard #6, #7) Materials: World map or globe Blank paper/marker/tape “Kurdish Folk Music from Western Iran”: http://www.folkways.si.edu/kurdish-folk-music-from-western-iran/islamica- -

Imagined Kurds

IMAGINED KURDS: MEDIA AND CONSTRUCTION OF KURDISH NATIONAL IDENTITY IN IRAQ A Thesis submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for / \ 5 the Degree 3C Master of Arts In International Relations by Miles Theodore Popplewell San Francisco, California Fall 2017 Copyright by Miles Theodore Popplewell 2017 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Imagined Kurds by Miles Theodore Popplewell, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Arts in International Relations at San Francisco State University. Assistant Professor Amy Skonieczny, Ph.D. Associate Professor IMAGINED KURDS Miles Theodore Popplewell San Francisco, California 2017 This thesis is intended to answer the question of the rise and proliferation of Kurdish nationalism in Iraq by examining the construction of Kurdish national identity through the development and functioning of a mass media system in Iraqi Kurdistan. Following a modernist approach to the development and existence of Kurdish nationalism, this thesis is largely inspired by the work of Benedict Anderson, whose theory of nations as 'imagined communities' has significantly influenced the study of nationalism. Kurdish nationalism in Iraq, it will be argued, largely depended upon the development of a mass media culture through which political elites of Iraqi Kurdistan would utilize imagery, language, and narratives to develop a sense of national cohesion amongst their audiences. This thesis explores the various aspects of national construction through mass media in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, in mediums such as literature, the internet, radio, and television. -

Ahmad, Chnor Jaafar (2019) the Dilemma of Kurdish Nationalism As a Result of International Treaties and Foreign Occupations Between the Years 1850 to 1930

Ahmad, Chnor Jaafar (2019) The dilemma of Kurdish nationalism as a result of international treaties and foreign occupations between the years 1850 to 1930. MPhil(R) thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/41171/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] University of Glasgow College of Arts Graduate School THE DILEMMA OF KURDISH NATIONALISM AS A RESULT OF INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND FOREIGN OCCUPATIONS BETWEEN THE YEARS 1850 TO 1930 By Chnor Jaafar Ahmad Supervisor: Dr Michael Rapport A thesis submitted to the University of Glasgow in fulfillment of the requirement of the Degree of Master of Philosophy, April 2019. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................................ iv THESIS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................... v ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................................... -

Who Are the Kurds ?

WHO ARE THE KURDS ? History and Geography Homeland for the Kurdish people is the Zagros and Taurus mountain ranges of the Middle East known as Kurdistan (“place of the Kurds”). The area overlaps with Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Syria, and parts of the former Soviet Union. Kurds refer to the area of Kurdistan located in Turkey as “Northern Kurdistan;” in the area of Iran as “Eastern Kurdistan;” in Iraq as “Southern Kurdistan;” and in Syria as “Western Kurdistan.” They derive their collective culture and personality from life on these 10,000 feet massifs and make claim to this region long before the Arabs entered Mesopotamia and 3,000 years before the Turks arrived in Anatolia. Like the Persians, Kurds are of Indo-European origin and linked ethnically and historically with much of Persian history. Kurds today have no official country, though they are said to be one of the largest and oldest ethnic groups in the world … and the largest group of ethnic people without a country. Kurds trace their heritage back thousands of years and are linked historically with the Medes (“Darius the Mede”) of the ancient Medo-Persian Empire. Many Biblical stories are rooted in this history, including the Old Testament stories of Daniel, Esther, Nehemiah, and others. The Medes are also known historically for overthrowing the Assyrian Empire (in the region that is now Iraq) in 612 BCE. Some historians believe that the Arabs gave the name “Kurds” to these rugged people in the 7th century CE. During the Ottoman Empire (1534–1921), the Kurds came under the rule of two sovereigns: the Sultan in Istanbul and the Shah in Teheran. -

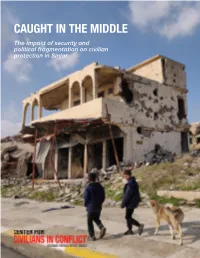

Caught in the Middle: the Impact of Security

CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE The impact of security and political fragmentation on civilian protection in Sinjar civiliansinconflict.org i RECOGNIZE. PREVENT. PROTECT. AMEND. PROTECT. PREVENT. RECOGNIZE. Cover: Children walking among the October 2020 rubble in Sinjar, February 2020. Credit: CIVIC/Paula Garcia T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] civiliansinconflict.org Table of Contents About Center for Civilians in Conflict .................................v Acknowledgments .................................................v Glossary .........................................................vi Executive Summary ................................................1 Recommendations .................................................4 Methodology .................................................... 6 Background .......................................................7 Sinjar’s Demographics ............................................10 Protection Concerns .............................................. 11 Barriers to Return ............................................... 11 Sunni Arabs Prevented from Returning ............................15 Lack of Government Services Impacting Rights ....................18 Security Actors’ Behavior and Impact on Civilians .................22 Civilian Harm from Turkish Airstrikes ............................. 27 Civilian Harm from ERW and IED Contamination ..................28 Delays in Accessing Compensation ..............................31 Reconciliation and Justice Challenges ...........................32 -

Under the Mountains: Kurdish Oil and Regional Politics

January 2016 Under the Mountains: Kurdish Oil and Regional Politics OIES PAPER: WPM 63 Robin Mills* The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2016 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78467-049-8 *Non-Resident Fellow for Energy at the Brookings Doha Center, CEO of Qamar Energy (Dubai) and Research Associate, Oxford Institute for Energy Studies Under the Mountains: Kurdish Oil and Regional Politics i Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. iii 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background: a Brief History of Oil and Gas in the Kurdish Region of Iraq ................................ 2 2.1. Political history ........................................................................................................................ 2 2.2. Petroleum history ...................................................................................................................