Horses As Heroes in Medieval Islamicate Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi

Official Digitized Version by Victoria Arakelova; with errata fixed from the print edition ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI YEREVAN SERIES FOR ORIENTAL STUDIES Edited by Garnik S. Asatrian Vol.1 SIAVASH LORNEJAD ALI DOOSTZADEH ON THE MODERN POLITICIZATION OF THE PERSIAN POET NEZAMI GANJAVI Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies Yerevan 2012 Siavash Lornejad, Ali Doostzadeh On the Modern Politicization of the Persian Poet Nezami Ganjavi Guest Editor of the Volume Victoria Arakelova The monograph examines several anachronisms, misinterpretations and outright distortions related to the great Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi, that have been introduced since the USSR campaign for Nezami‖s 800th anniversary in the 1930s and 1940s. The authors of the monograph provide a critical analysis of both the arguments and terms put forward primarily by Soviet Oriental school, and those introduced in modern nationalistic writings, which misrepresent the background and cultural heritage of Nezami. Outright forgeries, including those about an alleged Turkish Divan by Nezami Ganjavi and falsified verses first published in Azerbaijan SSR, which have found their way into Persian publications, are also in the focus of the authors‖ attention. An important contribution of the book is that it highlights three rare and previously neglected historical sources with regards to the population of Arran and Azerbaijan, which provide information on the social conditions and ethnography of the urban Iranian Muslim population of the area and are indispensable for serious study of the Persian literature and Iranian culture of the period. ISBN 978-99930-69-74-4 The first print of the book was published by the Caucasian Centre for Iranian Studies in 2012. -

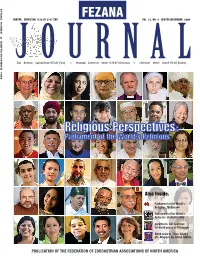

FEZANA Journal Do Not Necessarily Reflect the Views of FEZANA Or Members of This Publication's Editorial Board

FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA WINTER ZEMESTAN 1378 AY 3747 ZRE VOL. 23, NO. 4 WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 G WINTER/DECEMBER 2009 JOURNALJODae – Behman – Spendarmad 1378 AY (Fasli) G Amordad – Shehrever – Meher 1379 AY (Shenshai) G Shehrever – Meher – Avan 1379 AY (Kadimi) Also Inside: Parliament oof the World’s Religions, Melbourne Parliamentt oof the World’s Religions:Religions: A shortshort hihistorystory Zarathustiss join in prayers for world peace in Pittsburgh Book revieew:w Thus Spake the Magavvs by Silloo Mehta PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA afezanajournal-winter2009-v15 page1-46.qxp 11/2/2009 5:01 PM Page 1 PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 23 No 4 Winter / December 2009 Zemestan 1378 AY - 3747 ZRE President Bomi V Patel www.fezana.org Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor 2 Editorial [email protected] Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar Dolly Dastoor Assistant to Editor Dinyar Patel Consultant Editor: Lylah M. Alphonse, 4ss Coming Event [email protected] Graphic & Layout: Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info Cover design: Feroza Fitch, 5 FEZANA Update [email protected] Publications Chair: Behram Pastakia Columnists: 16 Parliament of the World’s Religions Hoshang Shroff: [email protected] Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi : [email protected] Yezdi Godiwalla [email protected] Behram Panthaki: [email protected] 47 In the News Behram Pastakia: [email protected] Mahrukh Motafram: [email protected] Copy editors: R Mehta, V Canteenwalla -

Homage Unto Ahura Mazda

Homage Unto Ahura Mazda By Dastur Dr. M. N. Dhalla www.Zarathushtra.com Table of Contents Homage Unto Ahura Mazda TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................... I CHAPTER I .................................................................................................................................. 1 THOU ART ALL IN ALL TO ME, AHURA MAZDA ............................................................................ 2 THY NAME IS ABOVE ALL NAMES, AHURA MAZDA ...................................................................... 3 THOU ART THE CREATOR OF ALL, AHURA MAZDA....................................................................... 4 THOU ART OUR NEAREST AND DEAREST, AHURA MAZDA............................................................ 5 THOU ART ALL-GOOD, AHURA MAZDA........................................................................................ 6 THOUGH INVISIBLE THYSELF, THOU ART ALL-SEEING, AHURA MAZDA ...................................... 7 THOU ART LIGHT, AHURA MAZDA............................................................................................... 8 THOU ART THE SAME FROM AGE TO AGE, AHURA MAZDA ........................................................... 9 THOU ART AGELESS, AHURA MAZDA........................................................................................ 10 THY WILL IS THE POLE STAR OF MY LIFE, AHURA MAZDA ......................................................... 11 MY HEART LONGS FOR THEE, -

Siavash Status in Mythology and Rituals

International Journal of History and Cultural Studies (IJHCS) Volume2, Issue 3, 2016, PP 6-16 ISSN 2454-7646 (Print) & ISSN 2454-7654 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0203002 www.arcjournals.org Siavash Status in Mythology and Rituals Seyed Salam Fathi Master in ancient history of Iran, Department of History Islamic Azad University of Tehran Central Branch, Iran [email protected] Abstract: Siavash character as one of the central figures of Iran's national epic is seen in myth, the Avesta, Pahlavi texts, and archaeological findings. Siavash etymology and discussing his status in Iranian myths and comparing it with legends of different nations in five areas of "rituals," "the first man," "the issue of martyrdom," "plants of Siavash blood," and "mourning for Siavash" are among the issues that have been considered in this study. Attention to Siavash's position in Iranian rituals and continuation of his social functions in the form of traditions such as "Haji Firouz," "Nowruz," and "Ceremony of cock killing" are of the constituents and characteristics that are studied in close contact with each other. Siavash presence in the text such as Avesta, Bundahisn and Numinous wisdom is the very presence in myth and Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, so the most important actions he has have also been studied in these texts. Central structure and thought-centeredness in each of the chapters mentioned are based on the idea of "Mehrdad Bahar" based on Siavash's being "Herbal God," so it is obvious that the concept of martyrdom, plant of Siavash blood, and mourning are all affected by this opinion. -

Ruka'at-I-Alamgiri

nm'V5 UC-NRLF Ruka'aH^lamgin or Cemrs of flurungzcbe [WITH HISTORICAL AND EXPLANATORY NOTES] Translated from the original Persian into English BY ,JAMSH1D H. BIL1MORIA, B.A. [Registered under Act XXV of 1867. ) LUZAC & Co., 46, Great Russeli, Street, London; *:vj V;/ BOMBAY: CHERAG PRINTING PRESS, 1908. - \\ m All Rights Reserved BY THE TRANSLATOR, JAMSHID H. BILIMORIA, l.a. r«» f^i PREFACE. There are three collections of Aurungzebe's letters. " " First, the Ruka'at-i-Alamgiri," or the Kaliinat-i- Taiyibat," collected and published by Inayat Allah, one of secretaries " his principal ; second, the Rakaim-i- Karaim," by the son of another secretary Abdul Karim and the " Amir Khan ; third, Dastur-al-Amal Aghahi," collected from various sources thirty-eight years after the emperor's death by a learned servant of Raja Aya Mai under the Raja's order. There is still another " collection bearing the name of the Adab-i-Alamgiri," and comprising letters written by Aurungzebe to his father, his sons, and his officers. These letters have no dates and have no order. I have tried my best to assign dates to most of them. But it is impossible to do so in the case of each and every one of them, as some of them have no historical connection. Most of the letters seem to have been written when Aurungzebe was engaged in his great Deccan War (1683-1707), especially during the latter period of the war. These letters generally depict Aurungzebe's private life. Occasionally they allude to minor historical events which happened in his or in his father's time. -

A K I N G S B O O K O F K I N G S the Houghton Shah-Nameh The

A KINGS BOOK OF KINGS The Houghton Shah-nameh The Metropolitan Museum of Art A,k A KING'S BOOK OF KINGS THE HOUGHTON SHAH-NAMEH SYNOPSES OF THE STORIES ILLUSTRATED IN THE EXHIBITION A KING'S BOOK OF KINGS May 4 - October 31, 1972 Compiled by Marie Lukens Swietochowski and Suzanne Boorsch The Metropolitan Museum of Art The Shah-nameh, Persia's Book of Kings, recounts the history of Iran's ancient empire from its legendary birth to its downfall in the middle of the seventh century at the hands of Arab armies. Around the year 975, at a time of renewed national consciousness, the poet Firdowsi of Tus began writing this great epic, a task lasting about thirty-five years. In time, it became the custom among various major and minor rulers of Iran to have their own Shah-nameh copied out and illus trated by the best artists their prestige could command. The Houghton Shah-nameh was commissioned for the second ruler of the Safavid Dynasty, Shah Tahmasp, early in a reign that began in 1524. It contains an unprecedented 258 miniature paintings, some as large as 11 x 14 inches, and represents a culmination of a long tradition in this art. Seventy-five miniatures from the manuscript were selected for this exhibition. The stories here are arranged in consecutive order as they appear in the Shah-nameh, with the folio number, recto or verso, indicated. The folio numbers are indicated above the miniatures in the exhibition, and the titles here correspond to those in the exhibition. -

CENTURY PANEGYRIC 1ST AZRAQI of HERAT by LEONARD WILLIAM

A STUDY OF THE IMAGERY OF THE ELEVENTH CENTURY PANEGYRIC 1ST AZRAQI OF HERAT by LEONARD WILLIAM HARROW A Thesis Presented for the Degree of FJfrD, - In the University of London 1973* ProQuest Number: 10672856 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672856 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 A feature of the work of the eleventh century poet, AzraqI of Herat, is his use of elaborate and complex imagery. This thesis is a study of AzraqI' s imagery with a view to examining his images and any allusions associated with them. A complete understanding of such features will lead to a better comprehension of the world in which the poet lived and worked. To achieve this end a number of prominent themes in AzraqI's gaga1 id have been examined. In general they may be divided into those of the intellectual sphere (the picture of the universe and philoso phical ideas), themes associated with the natural world (the place of minerals and precious stones, flowers and animals), and aspects of the world created by man. -

60 Manifestation of Evil in Persian Mythology from the Perspective Of

Manifestation of Evil in Persian Mythology from the Perspective of the Zoroastrian Religion Seyed Reza Ebrahimi1 and Elnaz Valaei Bakhshayesh2 1Department of Foreign Languages and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Sanandaj Branch, Sanandaj, Iran [email protected] 2 Elnaz Valaei Bakhshayesh [email protected] Abstract: Zoroastrian religion, which was first founded in ancient Iran before Islam, introduces the constant conflict between Ahura Mazda, known as the benevolent, omniscient and endless light, and Ahriman which is the endless and absolute darkness and aims to demolish Ahura mazda. For this purpose, Ahriman creates six demons of evil thought including Akoman (equivalent to Avestan Akem Manah), Indar, Naonhaithya, Saurva, Taurvi and finally Zauri which are incarnated as villains to counter Ahura Mazda’s creation and good thoughts. In a mythological legend like Shahnameh , Ferdowsi distinctly depicts the battle between evil and human being which ultimately leads to the victory of benevolence. This paper aims to investigate the mythological villainy of Akoman and its defeat by Rustam in Ferdowsi’s great epic Shahnameh. [S.R. Ebrahimi, E.Valaei Bakhshayesh. Manifestation of Evil in Persian Mythology from the Perspective of the Zoroastrian Religion. Am Sci 2021;17(5):60-65]. ISSN 1545-1003 (print); ISSN 2375-7264 (online). http://www.j ofamericanscience.org 7. doi:10.7537/marsjas170521.07. Key words: Zoroastrianism, Villain, Daeva, Ahriman, Ahura Mazda, Aka Manah, myth. 1. Introduction ideals like Honesty or natural events such as storm or Hinnels begins his book Persian mythology by they were adventurous heroes like Indra and describing the function of myth. -

Download Download

JIIA.eu Journal of Intercultural and Interdisciplinary Archaeology Composite Creatures in Sasanian Art According to Some Numismatic and Sphragistic Evidence Matteo Compareti School of History and Civilization, Shaanxi Normal University [email protected] The reign of the Sasanian Dynasty (224–651) received great attention in the works of Muslim authors who usually referred to this period as the “golden age” of pre-Islamic Persia.1 It is however worth noting that objects of art incontrovertibly attributable to the Sasanians are not very numerous. To be precise, the entire production of pre-Islamic Iranian arts is not very big especially when compared to other civilizations of the past that were in contact with Persia and Central Asia such as the Greco-Roman, Indian, and Chinese. Among those specimens that can incontestably be considered as products of artists active at the Sasanian court there are few archaeological sites whose investigation continues (slowly) at present, less than forty rock reliefs, and very few objects of toreutic or other luxury arts (Harper 2006; Callieri 2014). In the last thirty years, scholars mainly focused their efforts in specific fields of study such as numismatics and sphragistics (Gyselen 2006; Callieri 2014). Sasanian coins, seals, and sealings present in some cases fabulous creatures that are composed of parts of different animals. Such creatures are not always clearly identifiable because they are just partially represented. This is the case of a group of controversial coins of Bahram II (276–293) embellished on the obverse with unusual double or triple busts in profile. In the first variant, the king is represented together with his queen in profile facing right. -

The Shahnama;

TRUBNER'S ORIENTAL SERIES. DONE INTO ENGLISH BY ARTHUR GEORGE WARNER, M.A. AND EDMOND WARNER, B.A. "The homes that are the dwellings of to-day Will sink 'neath shower and sunshine to decay, But storm and rain shall never mar what I " Have built the palace of my poetry. FlBDAUSl VOL. V LONDON KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO. L"> DRYDEN HOUSE, GERRARD STREET, W. 1910 The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved Printed by BALLANTYNK, HANSON & Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh CONTENTS PAGE ABBREVIATIONS 3 NOTE ON PRONUNCIATION 5 THE KAIANIAN DYNASTY (continued) GUSHTASP PART I. THE COMING OF ZARDUHSHT AND THE WAR WITH ARJASP SECT. 1. How Firdausi saw Dakiki in a Dream ... 30 2. How Luhrasp went to Balkh and how Gushtasp sat upon the Throne 31 3. How Zarduhsht appeared and how Gushtasp ac- cepted his Evangel 33 4. How Gushtasp refused to Arjasp the Tribute for Iran 35 5. How Arjasp wrote a Letter to Gushtasp . 37 6. How Arjasp sent Envoys to Gushtasp ... 40 7. How Zarir made Answer to Arjasp ... 42 8. How the Envoys returned to Arjasp with the Letter of Gushtasp ..... 43 9. How Gushtasp assembled his Troops ... 47 10. How Jamasp foretold the Issue of the Battle to Gushtasp ........ 48 n. How Gushtasp and Arjasp arrayed their Hosts . 54 12. The Beginning of the Battle between the Iranians and Turanians, and how Ardshir, Shiru, and Shidasp were slain ...... 56 13. How Girami, Jamasp's Son, and Nivzar were slain . 58 14. How Zarir, the Brother of Gushtasp, was slain by Bidirafsh 61 15. -

Studies in Persian Cultural History

Studies in Persian Cultural History Editors Charles Melville Cambridge University Gabrielle van den Berg Leiden University Sunil Sharma Boston University VOLUME 2 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/spch © 2012 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 22863 4 contents vii CONTENTS Contributors . ix List of illustrations. xv Abbreviations. xix Colour Plates . following xx Introduction Charles Melville . 1 PTAR ONE THE reception OF THE SHAHNAMA: later EPICS Tracking the Shahnama Tradition in Medieval Persian Folk Prose Julia Rubanovich . 11 Demons in the Persian Epic Cycle: The Div Shabrang in the Leiden Shabrangnama and in Shahnama Manuscripts Gabrielle van den Berg. 35 Faramarz’s Expedition to Qannuj and Khargah: Mutual Influences of the Shahnama and the Longer Faramarznama Marjolijn van Zutphen . 49 The Influence of the Shahnama in the Extended Version of Arday Virafnama by Zartusht Bahram Olga Yastrebova . 79 Picturing Evil: Images of Divs and the Reception of the Shahnama Francesca Leoni . 101 PTAR Two THE SHAHNAMA IN NEIGHBOURING LANDS The Reception of Firdausi’s Shahnama Among the Ottomans Jan Schmidt . 121 © 2012 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978 90 04 22863 4 viii contents The Illustration of the Shahnama and the Art of the Book in Ottoman Turkey Zeren Tanındı . 141 The Shahnama of Firdausi in the Lands of Rum Lâle Uluç. 159 Bahram’s Feat of Hunting Dexterity as Illustrated in Firdausi’s Shahnama, Nizami’s Haft Paikar and Amir Khusrau’s Hasht Bihisht Adeela Qureshi . 181 The Samarqand Shahnamas in the Context of Dynastic Change Karin Ruehrdanz . 213 PTAR THREE MANUSCRIPT studies Mapping Illustrated Folios of Shahnama Manuscripts: The Concept and Its Uses Farhad Mehran.