PARGITER-Ancient-Indian-Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of Marathi and Gujarati Printed Books in the Library of The

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/catalogueofmaratOObrituoft : MhA/^.seor,. b^pK<*l OM«.^t«.lT?r>">-«-^ Boc.ic'i vAf. CATALOGUE OF MARATHI AND GUJARATI PRINTED BOOKS IN THE LIBRARY OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. BY J. F. BLUMHARDT, TEACHBB OF BENBALI AT THE UNIVERSITY OP OXFORD, AND OF HINDUSTANI, HINDI AND BBNGACI rOR TH« IMPERIAL INSTITUTE, LONDON. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM. •» SonKon B. QUARITCH, 15, Piccadilly, "W.; A. ASHER & CO.; KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TKUBNER & CO.; LONGMANS, GREEN & CO. 1892. /3 5^i- LONDON ! FEINTED BY GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, VD., ST. JOHN'S HOUSE, CLKBKENWEIL BOAD, E.C. This Catalogue has been compiled by Mr. J. F. Blumhardt, formerly of tbe Bengal Uncovenanted Civil Service, in continuation of the series of Catalogues of books in North Indian vernacular languages in the British Museum Library, upon which Mr. Blumhardt has now been engaged for several years. It is believed to be the first Library Catalogue ever made of Marathi and Gujarati books. The principles on which it has been drawn up are fully explained in the Preface. R. GARNETT, keeper of pbinted books. Beitish Museum, Feb. 24, 1892. PEEFACE. The present Catalogue has been prepared on the same plan as that adopted in the compiler's " Catalogue of Bengali Printed Books." The same principles of orthography have been adhered to, i.e. pure Sanskrit words (' tatsamas ') are spelt according to the system of transliteration generally adopted in the preparation of Oriental Catalogues for the Library of the British Museum, whilst forms of Sanskrit words, modified on Prakrit principles (' tadbhavas'), are expressed as they are written and pronounced, but still subject to a definite and uniform method of transliteration. -

Narsinh Mehta - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Narsinh Mehta - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Narsinh Mehta(1414? – 1481?) Narsinh Mehta (Gujarati:?????? ?????)also known as Narsi Mehta or Narsi Bhagat was a poet-saint of Gujarat, India, and a member of the Nagar Brahmins community, notable as a bhakta, an exponent of Vaishnava poetry. He is especially revered in Gujarati literature, where he is acclaimed as its Adi Kavi (Sanskrit for "first among poets"). His bhajan, Vaishnav Jan To is Mahatma Gandhi's favorite and has become synonymous to him. <b> Biography </b> Narsinh Mehta was born in the ancient town of Talaja and then shifted to Jirndurg now known as Junagadh in the District of Saurashtra, in Vaishnava Brahmin community. He lost his mother and his father when he was 5 years old. He could not speak until the age of 8 and after his parents expired his care was taken by his grand mother Jaygauri. Narsinh married Manekbai probably in the year 1429. Narsinh Mehta and his wife stayed at his brother Bansidhar’s place in Junagadh. However, his cousin's wife (Sister-in-law or bhabhi) did not welcome Narsinh very well. She was an ill- tempered woman, always taunting and insulting Narsinh mehta for his worship (Bhakti). One day, when Narasinh mehta had enough of these taunts and insults, he left the house and went to a nearby forest in search of some peace, where he fasted and meditated for seven days by a secluded Shiva lingam until Shiva appeared before him in person. -

Dear Friends, Scholars and Critics This Is a Soft Copy of My Doctoral

Dear Friends, Scholars and Critics This is a soft copy of my doctoral dissertation written during the final five years of the previous millennium .Apart from a fairly large theoretical component dealing with translation theory, practice of translation and translation studies, it consists of around ninety compositions of Narsinh Mehta (c. 15th century AD), one of the greatest poets of Gujarat translated by me into English. Besides a critical appreciation of his works, the translations are framed with chapters discussing his life, works and the cultural context in which they were composed. I have been working on the translations and they have metamorphosed into a very different avatar today. However, those presented here are the ones I submitted for the degree. There are some slight changes in this copy owning to my ignorance of formatting methods. The bibliography which appears at the end of the thesis comes before the `notes and references of the soft copy. The notes and references for the individual chapters now appear at the end of the thesis. The `Table of Contents’ is merely a showpiece- it doesn’t indicate the specified pages in this copy. I don’t intend to publish this thesis in the present form and it has appeared in parts in many places. The work which I started with my doctoral research is actually a work in `progress’ and I find it interesting to look back where I was some eight years ago. I would be honoured to hear your critical comments and reactions to my work. Sachin Ketkar Baroda, 27 December 2007 TRANSLATION OF NARSINH MEHTA'S POEMS INTO ENGLISH: WITH A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Thesis Submitted For The Degree Of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS OF SOUTH GUJARAT UNIVERSTIY SURAT RESEARCH CANDIDATE SACHIN C. -

Death of the Aryan Invasion Theory by Stephen Knapp

Death of the Aryan Invasion Theory By Stephen Knapp With only a small amount of research, a person can discover that each area of the world has its own ancient culture that includes its own gods and legends about the origins of various cosmological realities, and that many of these are very similar. But where did all these stories and gods come from? Did they all spread around the world from one particular source, only to change according to differences in language and customs? If not, then why are some of these gods and goddesses of various areas of the world so alike? Unfortunately, information about prehistoric religion is usually gathered through whatever remnants of earlier cultures we can find, such as bones in tombs and caves, or ancient sculptures, writings, engravings, wall paintings, and other relics. From these we are left to speculate about the rituals, ceremonies, and beliefs of the people and the purposes of the items found. Often we can only paint a crude picture of how simple and backwards these ancient people were while not thinking that more advanced civilizations may have left us next to nothing in terms of physical remains. They may have built houses out of wood or materials other than stone that have since faded with the seasons, or were simply replaced with other buildings over the years, rather than buried by the sands of time for archeologists to unearth. They also may have cremated their dead, as some societies did, leaving no bones to discover. Thus, without ancient museums or historical records from the past, there would be no way of really knowing what the prehistoric cultures were like. -

In Search of Lord Rama's Sister

Hiranyagarbha Vol. 2 No. 4–38 Final 15.01.10 In Search of Lord Rama’s Sister My favourite period of the year, the ten days of who is known to have ‘directed’ the Ramayana’s di- Sree Sree Durga Puja or Navratri, had commenced. vine play - it now seemed to me that every enlight- Just a few days after Mahalaya, I paid a visit to the ened one except probably the principal actors knew Ashram. During a conversation with Sadhvi what was going to happen. I began to concentrate on Sanyuktanandamoyee, she mentioned that earlier in the actual text where the King Dasaratha’s minister the week, Sree Sree Maa was talking about King Sumantra talks to his king. Dasaratha’s daughter, Shanta Devi. “King Dasaratha’s It goes as follows: “O great King, let me tell you daughter!!” I asked, taken quite by surprise. “Yes, Maa what has been stated by the ever-benevolent great mentioned that Lord Rama had an elder sister, about sage Sanat Kumara, the finest among the divine ones. whom there is reference in the Ramayana, though Kindly listen to these favourable words of immense most people are unaware of her existence”, replied value (of the sage) - ‘In the Ikshvaku dynasty will be Sanyuktanandamoyee and continued saying, “From born in future a virtuous king called Dasaratha, who the way Sree Sree Maa talked about Devi Shanta, it will be firm and true to his words. He will forge a long- seems to me that there is more about this matter that standing friendship with the king of Anga (assumed to needs to be unearthed.” This was a bit too intriguing be the region of modern Assam), who in turn will have to ignore especially because earlier investigations of a daughter who brings great fortune, named Shanta. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

The Study and Practice of Yoga

THE STUDY AND PRACTICE OF YOGA AN EXPOSITION OF THE YOGA SUTRAS OF PATANJALI VOLUME II – SADHANA PADA, VIBHUTI PADA AND KAIVALYA PADA SWAMI KRISHNANANDA The Divine Life Society Sivananda Ashram, Rishikesh, India Website: www.swami-krishnananda.org ABOUT THIS EDITION Though this eBook edition is designed primarily for digital readers and computers, it works well for print too. Page size dimensions are 5.5" x 8.5", or half a regular size sheet, and can be printed for personal, non-commercial use: two pages to one side of a sheet by adjusting your printer settings. 2 CONTENTS THE SADHANA PADA Chapter 52: Yoga Practice: A Series of Positive Steps ................ 7 Chapter 53: A Very Important Sadhana ........................................ 21 Chapter 54: Practice Without Remission of Effort ................... 31 Chapter 55: The Cause of Bondage.................................................. 43 Chapter 56: Lack of Knowledge is the Source of Suffering .... 55 Chapter 57: The Four Manifestations of Ignorance ................. 67 Chapter 58: Pursuit of Pleasure is Invocation of Pain ............. 80 Chapter 59: The Self-Preservation Instinct ................................. 94 Chapter 60: Tracing the Ultimate Cause of Any Experience ........................................................................... 106 Chapter 61: How the Law of Karma Operates ......................... 118 Chapter 62: The Perception of Pleasure and Pain ................. 131 Chapter 63: The Cause of Unhappiness ...................................... 141 Chapter -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

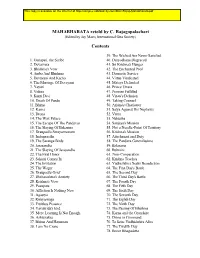

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

My HANUMAN CHALISA My HANUMAN CHALISA

my HANUMAN CHALISA my HANUMAN CHALISA DEVDUTT PATTANAIK Illustrations by the author Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017 7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj New Delhi 110002 Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Illustrations Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Cover illustration: Hanuman carrying the mountain bearing the Sanjivani herb while crushing the demon Kalanemi underfoot. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-291-3770-8 First impression 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The moral right of the author has been asserted. This edition is for sale in the Indian Subcontinent only. Design and typeset in Garamond by Special Effects, Mumbai This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. To the trolls, without and within Contents Why My Hanuman Chalisa? The Text The Exploration Doha 1: Establishing the Mind-Temple Doha 2: Statement of Desire Chaupai 1: Why Monkey as God Chaupai 2: Son of Wind Chaupai 3: -

A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism

A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism Dr Jagraj Singh A publication of Sikh University USA Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 1 A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism A comparative study of Sikhism and Hinduism Contents Page Acknowledgements 4 Foreword Introduction 5 Chapter 1 What is Sikhism? 9 What is Hinduism? 29 Who are Sikhs? 30 Who are Hindus? 33 Who is a Sikh? 34 Who is a Hindu? 35 Chapter 2 God in Sikhism. 48 God in Hinduism. 49 Chapter 3 Theory of creation of universe---Cosmology according to Sikhism. 58 Theory of creation according to Hinduism 62 Chapter 4 Scriptures of Sikhism 64 Scriptures of Hinduism 66 Chapter 5 Sikh place of worship and worship in Sikhism 73 Hindu place of worship and worship in Hinduism 75 Sign of invocation used in Hinduism Sign of invocation used in Sikhism Chapter 6 Hindu Ritualism (Karm Kanda) and Sikh view 76 Chapter 7 Important places of Hindu pilgrimage in India 94 Chapter 8 Hindu Festivals 95 Sikh Festivals Chapter 9 Philosophy of Hinduism---Khat Darsan 98 Philosophy of Sikhism-----Gur Darshan / Gurmat 99 Chapter 10 Panjabi language 103 Chapter 11 The devisive caste system of Hinduism and its rejection by Sikhism 111 Chapter 12 Religion and Character in Sikhism------Ethics of Sikhism 115 Copyright Dr. Jagraj Singh 2 A Comparative Study of Sikhism and Hinduism Sexual morality in Sikhism Sexual morality in Hinduism Religion and ethics of Hinduism Status of woman in Hinduism Chapter13 Various concepts of Hinduism and the Sikh view 127 Chapter 14 Rejection of authority of scriptures of Hinduism by Sikhism 133 Chapter 15 Sacraments of Hinduism and Sikh view 135 Chapter 16 Yoga (Yogic Philosophy of Hinduism and its rejection in Sikhism 142 Chapter 17 Hindu mythology and Sikh view 145 Chapter 18 Un-Sikh and anti-Sikh practices and their rejection 147 Chapter 19 Sikhism versus other religious aystems 149 Glossary of common terms used in Sikhism 154 Bibliography 160 Copyright Dr. -

Music of the Soul

Master E.K. MUSIC OF THE SOUL MUSIC OF T H E SOUL Master E.K. Master E.K. Book Trust VISAKHAPATNAM – 530051 © Master E.K. Book Trust Available online: Master E.K. Spiritual and Service Mission www.masterek.org Institute for Planetary Synthesis www.ipsgeneva.com PREFACE Every one of us has the following layers of consciousness which we can easily recognise: 1. The point of consciousness which we call the individuality. Around it all other things are centred. 2. The mind that recognises its own existence. 3. The mind that comes out through the senses and makes a contact with “others”. 4. The mind that knows and decides. 5. The mind that establishes its relationships with others. 6. The light that recognises itself existing in others. 7. The one who lives in all in the form of Love. There are people who live in each of these seven layers of consciousness. A living being awakens as the central point of the globe of one’s own existence (individuality). It takes up its journey and awakens into the second layer and the third layer of its own existence. This process is what the Ancients call Evolution. It continuous until it reaches the seventh, the outermost plane of consciousness, when it experiences the One Existence. This One Existence is liberation from the other six layers of consciousness. The PREFACE seventh layer, though it is absolute and beyond time and space, exists as the One Person who showers His Love upon the beings of all the other layers. This One Person can be called the Eternal Existence. -

![Text and Variations of the Mahabharata])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1437/text-and-variations-of-the-mahabharata-2011437.webp)

Text and Variations of the Mahabharata])

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340335175 Introduction (Samīkṣikā Series II: Text and Variation of the Mahābhārata [Samiksika Series II: Text and Variations of the Mahabharata]) Book · January 2009 CITATIONS READS 0 58 1 author: Kalyan Kumar Chakravarty Centurion University of Technology and Management 40 PUBLICATIONS 11 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Himalayan heritage View project Hindu Tradition View project All content following this page was uploaded by Kalyan Kumar Chakravarty on 01 April 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Samiksika Series II Text and Variations of the Mahabharata Samlksika Series No. 2 The Samlksika Series is aimed at compiling the papers presented by the various scholars during the seminars organized by the National Mission for Manuscripts. The seminars provide an interactive forum for scholars to present to a large audience, ideas related to the knowledge contained in India’s textual heritage. In keeping with the title, the Samlksika (research) Series is concerned with research papers of distinguished scholars and specialists in different intellectual disciplines of India. Text and Variations of the Mahabharata: Contextual, Regional and Performative Traditions Edited by Kalyan Kumar Chakravarty L ji ^ National Mission for Manuscripts Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. Introduction Kalyan Kumar Chakravarty The present volume delves into the textual, oral, visual and performing arts traditions of the Mahabharata in its ecumenical, classical versions and regional interpretations, in India and Southeast Asia, and in subaltern reconstructions.