Consumers As Players in the Russian Gas Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Energy Without Borders

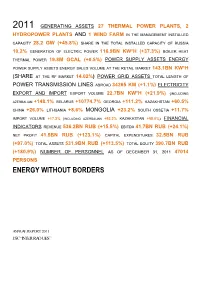

2011 GENERATING ASSETS 27 THERMAL POWER PLANTS, 2 HYDROPOWER PLANTS AND 1 WIND FARM IN THE MANAGEMENT INSTALLED CAPACITY 28.2 GW (+45.8%) SHARE IN THE TOTAL INSTALLED CAPACITY OF RUSSIA 10.2% GENERATION OF ELECTRIC POWER 116.9BN KW*H (+37.3%) BOILER HEAT THERMAL POWER 19.8M GCAL (+0.5%) POWER SUPPLY ASSETS ENERGY POWER SUPPLY ASSETS ENERGY SALES VOLUME AT THE RETAIL MARKET 143.1BN KW*H (SHARE AT THE RF MARKET 14.02%) POWER GRID ASSETS TOTAL LENGTH OF POWER TRANSMISSION LINES ABROAD 34265 KM (+1.1%) ELECTRICITY EXPORT AND IMPORT EXPORT VOLUME 22.7BN KW*H (+21.9%) (INCLUDING AZERBAIJAN +148.1% BELARUS +10774.7% GEORGIA +111.2% KAZAKHSTAN +60.5% CHINA +26.0% LITHUANIA +8.6% MONGOLIA +23.2% SOUTH OSSETIA +11.7% IMPORT VOLUME +17.2% (INCLUDING AZERBAIJAN +93.2% KAZAKHSTAN +58.0%) FINANCIAL INDICATORS REVENUE 536.2BN RUB (+15.5%) EBITDA 41.7BN RUB (+24.1%) NET PROFIT 41.5BN RUB (+123.1%) CAPITAL EXPENDITURES 32.5BN RUB (+97.0%) TOTAL ASSETS 531.9BN RUB (+113.5%) TOTAL EQUITY 390.7BN RUB (+180.9%) NUMBER OF PERSONNEL AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2011 47014 PERSONS ENERGY WITHOUT BORDERS ANNUAL REPORT 2011 JSC “INTER RAO UES” Contents ENERGY WITHOUT BORDERS.........................................................................................................................................................1 ADDRESS BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD OF JSC “INTER RAO UES”..............................................................................................................8 1. General Information about the Company and its Place in the Industry...........................................................10 1.1. Brief History of the Company......................................................................................................................... 10 1.2. Business Model of the Group..........................................................................................................................12 1.4. -

Annual Report ‘06 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT ‘06 CONTENTS MESSAGE TO SHAREHOLDERS ————————————————————————————— 4 MISSION AND STRATEGY ———————————————————————————————— 7 COMPANY OVERVIEW ————————————————————————————————— 13 ² GENERAL INFORMATION 13 ² GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION 14 ² CALENDAR OF KEY 2006 EVENTS 15 ² REORGANIZATION 16 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE —————————————————————————————— 21 ² PRINCIPLES AND DOCUMENTS 21 ² MANAGEMENT BODIES OF THE COMPANY 22 ² CONTROL BODIES 39 ² AUDITOR 40 ² ASSOCIATED AND AFFILIATED COMPANIES 40 ² INTERESTED PARTY TRANSACTIONS 41 SECURITIES AND EQUITY ——————————————————————————————— 43 ² CHARTER CAPITAL STRUCTURE 43 ² STOCK MARKET 44 ² DIVIDEND HISTORY 48 ² REGISTRAR 49 OPERATING ACTIVITIES. KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ——————————————— 51 ² GENERATING FACILITIES 51 ² FUEL SUPPLY 52 ² ELECTRICITY PRODUCTION 56 ² HEAT PRODUCTION 59 ² BASIC PRODUCTION ASSETS REPAIR 59 ² INCIDENT AND INJURY RATES. OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY 60 ² ENVIRONMENTAL SAFETY 61 ELECTRICITY AND HEAT MARKETS ——————————————————————————— 65 ² COMPETITIVE ENVIRONMENT. OVERVIEW OF KEY MARKETS 65 ² ELECTRICITY AND HEAT SALES 67 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW ————————————————————————————————— 73 ² FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 73 ² REVENUES AND EXPENSES BREAKDOWN 81 INVESTMENT ACTIVITIES ———————————————————————————————— 83 ² INVESTMENT STRATEGY 83 ² INVESTMENT PROGRAM 84 ² INVESTMENT PROGRAM FINANCING SOURCES 86 ² DEVELOPMENT PROSPECTS 87 INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DEVELOPMENT —————————————————————— 89 PERSONNEL AND SOCIAL POLICY. SOCIAL PARTNERSHIP ———————————————— 91 INFORMATION FOR INVESTORS AND SHAREHOLDERS —————————————————— -

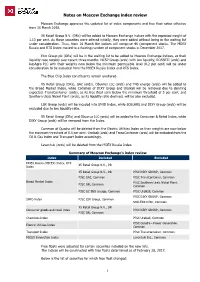

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

An Overview of Boards of Directors at Russia's Largest Public Companies

An Overview Of Boards Of Directors At Russia’s Largest Public Companies Andrei Rakitin Milena Barsukova Arina Mazunova Translated from Russian August 2020 Key Results According to information disclosed by 109 of Russia’s largest public companies: “Classic” board compositions of 11, nine, and seven seats prevail The total number of persons on Boards of the companies under study is not as low as it might seem: 89% of all Directors were elected to only one such Board Female Directors account for 12% and are more often elected to the audit, nomination, and remuneration committees than to the strategy committee Among Directors, there are more “humanitarians” than “techies,” while the share of “techies” among chairs is greater than across the whole sample The average age for Directors is 53, 56 for Chairmen, and 58 for Independent Directors Generation X is the most visible on Boards, and Generation Y Directors will likely quickly increase their presence if the impetuous development of digital technologies continues The share of Independent Directors barely reaches 30%, and there is an obvious lack of independence on key committees such as audit Senior Independent Directors were elected at 17% of the companies, while 89% of Chairs are not independent The average total remuneration paid to the Board of Directors is RUR 69 million, with the difference between the maximum and minimum being 18 times Twenty-four percent of the companies disclosed information on individual payments made to their Directors. According to this, the average total remuneration is approximately RUR 9 million per annum for a Director, RUR 17 million for a Chair, and RUR 11 million for an Independent Director The comparison of 2020 findings with results of a similar study published in 2012 paints an interesting dynamic picture. -

OEF 107 November 2016.Indd

NOVEMBER 2016: Issue 107 forum A QUARTERLY JOURNAL FOR DEBATING ENERGY ISSUES AND POLICIES It is well known that Russia is heavily not be practically possible, meaning CONTENTS dependent on its energy sector, from that oil and gas companies could face both an economic and a political a stealth increase in their overall tax Russian energy issues in a volatile perspective. As a result, the fall in the burden. environment oil price over the past two years and the Tatiana Mitrova then discusses one Russia’s macroeconomic problems and dramatic changes taking place in the of the key factors underpinning the the risks to the oil and gas sector global gas market are having signifi cant survival of Russia’s hydrocarbon Christopher Granville 4 consequences for both the Kremlin and industry in 2016, namely the devaluation Russia’s domestic energy companies. Cost dynamics in the Russian energy sector of the ruble and its impact on cost Tatiana Mitrova 7 However, instead of reviewing the competitiveness. The Russian increased risks for Russia from the The Rosneftization of the Russian oil sector government’s decision not to protect change in global energy markets, this Nina Poussenkova 9 the domestic currency as the oil price edition of the Oxford Energy Forum collapsed has signifi cantly enhanced Securing the future: the implications of discusses how Russia has started the position of exporting industries, India’s expanding role in the Russian oil to adapt its policies and commercial reducing their costs in US$ terms, sector strategies in a number of different areas. Vitaly Yermakov 12 but Mitrova argues that this benefi t Some of the new strategies appear very has limited further upside and could positive, while others carry inherent Ukraine’s dramatic gas import diversifi cation risks, but all show how the world’s indeed be reversed if the oil price Simon Pirani 15 largest producer of hydrocarbons is recovers. -

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals After the Crisis: Results of 2011

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals after the Crisis: Results of 2011 Report dated April 16, 2013 Moscow and New York, April 16, 2013 The Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, and the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment (VCC), a joint center of Columbia Law School and the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York, are releasing the results of their third survey of Russian multinationals today.1 The survey, conducted from November 2012 to February 2013, is part of a long-term study of the global expansion of emerging market non-financial multinational enterprises (MNEs).2 The present report covers the period 2009-2011. Highlights Russia is one of the leading emerging markets in terms of outward foreign direct investments (FDI). Such a position is supported not by several multinational giants but by dozens of Russian MNEs in various industries. Foreign assets of the top 20 Russian non-financial MNEs grew every year covered by this report and reached US$ 111 billion at the end of 2011 (Table 1). Large Russian exporters usually use FDI in support of their foreign activities. As a result, oil and gas and steel companies with considerable exports are among the leading Russian MNEs. However, representatives of other industries also have significant foreign assets. Many companies remained “regional” MNEs. As a result, more than 66% of the ranked companies’ foreign assets were in Europe and Central Asia, with 28% in former republics of the Soviet Union (Annex table 2). Due to the popularity of off-shore jurisdictions to Russian MNEs, some Caribbean islands and Cyprus attracted many Russian subsidiaries with low levels of foreign assets. -

A CITIZEN's GUIDE to NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES Part a Technical Report

A CITIZEN’S GUIDE TO NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES Part A Technical Report October 2008 Copyright © 2008 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 and The Center for Energy Economics/Bureau of Economic Geology Jackson School of Geosciences, The University of Texas at Austin 1801 Allen Parkway Houston, TX 77019 All rights reserved. This paper is an informal document intended to provide input for the selection of a sample of representative national oil companies to be analyzed within the context of the Study on National Oil Companies and Value Creation launched in March 2008 by the Oil, Gas, and Mining Policy Division of The World Bank. The manuscript of this paper has not been prepared in accordance with the procedures appropriate to formally edited texts. Some sources cited in this paper may be informal documents that are not readily available. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. This report may not be resold, reprinted, or redistributed for compensation of any kind without prior written permission. For free downloads of this paper or to make inquiries, please contact: Oil, Gas, and Mining Policy Division Center for Energy Economics The World Bank Bureau of Economic Geology 2121 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Jackson School of Geosciences Washington DC, 20433 The University of Texas at Austin Telephone: 202-473-6990 Telephone: +1 281-313-9753 Fax: 202-522 0395 Fax: +1 281-340-3482 Email: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.worldbank.org/noc. -

Overview of the Ukrainian Oil and Gas and Shale Gas Market Opportunities

1/25 Overview of the Ukrainian Oil & Gas and Shale Gas Market Opportunities by Lyubomyr Goncharuk Adviser to the Minister of Ecology and Natural Resources of Ukraine Canada - Ukraine Oil & Gas Opportunities Workshop, Kyiv, February 25-26, 2013 2/25 CONTENTS 1. Reserves & Resources 2. Production & Consumption 3. Opportunities Canada - Ukraine Oil & Gas Opportunities Workshop, Kyiv, February 25-26, 2013 3/25 1. Reserves & Resources Canada - Ukraine Oil & Gas Opportunities Workshop, Kyiv, February 25-26, 2013 4/25 Canada - Ukraine Four oil and gas provinces are recognized Oil & Gas Opportunities in the country, including 11 oil-gas Workshop, Kyiv basins and 35 prospective areas. February 25-26, 2013 Hydrocarbon deposits are being exploited for oil, gas, and condensate in the following regions: Oil & Gas 1/2 • A – the Eastern Region (Dniprovsko- Donetska Depression and northwestern Crystalline basement slopes portion of Donbas); Voronezhska Volyno- Podilska Dniprovsko-Donetska Depression A Plate • B – the Western Region (Volyno- B Kyiv Anticline Lvivskiy Podilska Plate, Fore-Carpathians, Trough Fore-Carpathian Trough Folded Carpathians Folded Carpathians, and Trans- Donbas Transcarpathians UKRAINIAN SHIELD Carpathians); • C – the Southern Region 200 km Fore-Crimean Depression (Prychornomorya, Crimea, and the Azov Sea Fore- exclusive marine economic zone of the Dobrugean C Scythian Trough Plate Black Sea and Azov Sea offshore). Black Sea Mountain Crimea 5/25 Canada - Ukraine In 2011, production amounted to 2.4 million Oil & Gas Opportunities tons of oil, 0.9 million tons of condensate, Workshop, Kyiv and 20.6 billion cubic meters of natural gas. February 25-26, 2013 The State Inventory includes 187 oil deposits Oil & Gas 2/2 (121 in production), 202 condensate deposits (142 in production), and 380 natural Crystalline basement slopes gas deposits (224 in production). -

Advisory Services and Technical Assistance to NJSC Naftogaz of Ukraine and the Government

INTEGRATED SAFEGUARDS DATA SHEET CONCEPT STAGE Report No.: 89642 Date ISDS Prepared/Updated: July 15, 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized I. BASIC INFORMATION A. Basic Project Data Country: Ukraine Project ID: P151927 Project Name: Advisory Services and Technical Assistance to NJSC "Naftogaz of Ukraine" and the Government of Ukraine on the Reform of the Natural Gas Sector Task Team Leader: Yadviga Semikolenova Estimated Appraisal Date: July, 25 2014 Estimated Board Date: Public Disclosure Authorized Managing Unit: GEEDR Lending Instrument: Sector(s): Oil and Gas Theme(s): Corporate Governance; State-Owned Enterprise Restructuring and Privatization; Regulation and Competition Policy Is this project processed under OP 8.50 (Emergency Recovery) or OP 8.00 No (Rapid Response to Crises and Emergencies)? Financing (in USD Million) Total Project Cost: EURO 2,035,000 Total Bank Financing: Total Cofinancing: Financing Gap: Public Disclosure Authorized Financing Source Amount BORROWER/RECIPIENT 0 Single Donor (EC) Trust Fund EURO 2,035,000 Total EURO 2,035,000 Environmental Category C Is this a Repeater project? No Is this a Transferred No project? B. Project Objectives Public Disclosure Authorized The objective of the project is to provide advisory services and technical assistance to NJSC "Naftogaz of Ukraine" and the Government of Ukraine on the reform and restructuring of the natural gas sector through: providing support the Government of Ukraine to develop and implement the outstanding key 1 reforms in the gas sector that are necessary for Ukraine to fulfill the legal commitments undertaken in the framework of membership of the Energy Community; and providing advisory services, in the form of a Project Implementation Unit (PIU), to NJSC "Naftogaz of Ukraine" to prepare bankable projects and to oversee their implementation together with the IFIs (EBRD and EIB). -

Cleaning up the Energy Sector

10 Cleaning Up the Energy Sector Victory is when we won’t buy any Russian gas. —Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk1 Ukraine’s energy sector is well endowed but extremely mismanaged. Since Ukraine’s independence, it has been the main source of top-level corruption, and its prime beneficiaries have bought the state. This long-lasting policy has undermined national security, caused unsustainable public costs, jeopardized the country’s balance of payments, led to massive waste of energy, and capped domestic production of energy. It is difficult to imagine a worse policy. In- stead, conditions should be created so that Ukraine can develop its substantial energy potential and become self-sufficient in coal and natural gas.2 The solution to these problems is no mystery and it has been elaborated in a large literature for the last two decades. To check corruption energy prices need to be unified. That means raising key prices four to five times, which will eliminate the large energy subsidies and stimulate energy saving, while also stimulating domestic production of all kinds of energy. To make this politi- cally possible, social compensation should be offered to the poorest half of the population. The energy sector suffers from many shortcomings, and most of these need to be dealt with swiftly. Otherwise, new rent-seeking interests will evolve, and soon they will become entrenched and once again impossible to defeat. The new government has a brief window of opportunity to address the most important issues. 1. “Ukraina osvoboditsya ot ‘gazovoi zavisimosti’ ot RF cherez 5 let—Yatsenyuk” [“Yatsenyuk: Ukraine Will Free Itself from Gas Dependence on Russia in 5 Years”], Ekonomichna pravda, Sep- tember 8, 2014. -

US Sanctions on Russia

U.S. Sanctions on Russia Updated January 17, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45415 SUMMARY R45415 U.S. Sanctions on Russia January 17, 2020 Sanctions are a central element of U.S. policy to counter and deter malign Russian behavior. The United States has imposed sanctions on Russia mainly in response to Russia’s 2014 invasion of Cory Welt, Coordinator Ukraine, to reverse and deter further Russian aggression in Ukraine, and to deter Russian Specialist in European aggression against other countries. The United States also has imposed sanctions on Russia in Affairs response to (and to deter) election interference and other malicious cyber-enabled activities, human rights abuses, the use of a chemical weapon, weapons proliferation, illicit trade with North Korea, and support to Syria and Venezuela. Most Members of Congress support a robust Kristin Archick Specialist in European use of sanctions amid concerns about Russia’s international behavior and geostrategic intentions. Affairs Sanctions related to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are based mainly on four executive orders (EOs) that President Obama issued in 2014. That year, Congress also passed and President Rebecca M. Nelson Obama signed into law two acts establishing sanctions in response to Russia’s invasion of Specialist in International Ukraine: the Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Trade and Finance Ukraine Act of 2014 (SSIDES; P.L. 113-95/H.R. 4152) and the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014 (UFSA; P.L. 113-272/H.R. 5859). Dianne E. Rennack Specialist in Foreign Policy In 2017, Congress passed and President Trump signed into law the Countering Russian Influence Legislation in Europe and Eurasia Act of 2017 (CRIEEA; P.L. -

(31) December 2014

The Year An Interview with Chairman Electrification in Pictures: of Completed Ins of the State Duma’s Committee some facts from the history and Expected Outs for Energy Ivan GRACHEV of energy posters 14 20 32 Magazine about Russia’s Power Industry ENERGY WITHOUT BORDERS № 6 (31) December 2014 – January 2015 Happy Payments! The industry is anticipating tougher measures against non- payers in the retail electricity market IN RUSSIAN AND ENGLISH peretok.ru ENERGETICS IN RUSSIA AND IN THE WORLD peretok.ru NETWORKED! Dear readers, he end of the year is the time to sum up results. One of the un- solved problems of the year of 2014 is the outstanding debt for power supply. As of November 1, the amount owed to guaranteed supply companies in Russia reached 165 billion rubles. At the same time, the guaranteed supply companies have to pay on the wholesale market just in time and are forced to arrange loans to fulfill their obligations. Consumers’ poor payment discipline caus- es payment problems along the entire chain, undermining power companies’ financial stability, while the situation with non-pay- ments adversely affects the industry as a whole. Today, power supply companies do everything possible to get their money from consumers, including sending notices, cutting off electricity supply, filing lawsuits, and, jointly with court bai- liffs, prohibiting debtors from travelling abroad. It is clear that power supply companies will not be able to address this problem independently; this will require a systematic approach at the highest Tlevel. The State Duma is now developing a whole series of amendments to legislation aimed at tightening payment discipline on the retail market.