Investment from Russia Stabilizes After the Global Crisis 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Expiry Notice

Expiry Notice 19 January 2018 London Stock Exchange Derivatives Expiration prices for IOB Derivatives Please find below expiration prices for IOB products expiring in January 2018: Underlying Code Underlying Name Expiration Price AFID AFI DEVELOPMENT PLC 0.1800 ATAD PJSC TATNEFT 58.2800 FIVE X5 RETAIL GROUP NV 39.2400 GAZ GAZPROM NEFT 23.4000 GLTR GLOBALTRANS INVESTMENT PLC 9.9500 HSBK JSC HALYK SAVINGS BANK OF KAZAKHSTAN 12.4000 HYDR PJSC RUSHYDRO 1.3440 KMG JSC KAZMUNAIGAS EXPLORATION PROD 12.9000 LKOD PJSC LUKOIL 67.2000 LSRG LSR GROUP 2.9000 MAIL MAIL.RU GROUP LIMITED 32.0000 MFON MEGAFON 9.2000 MGNT PJSC MAGNIT 26.4000 MHPC MHP SA 12.8000 MDMG MD MEDICAL GROUP INVESTMENTS PLC 10.5000 MMK OJSC MAGNITOGORSK IRON AND STEEL WORKS 10.3000 MNOD MMC NORILSK NICKEL 20.2300 NCSP PJSC NOVOROSSIYSK COMM. SEA PORT 12.9000 NLMK NOVOLIPETSK STEEL 27.4000 NVTK OAO NOVATEK 128.1000 OGZD GAZPROM 5.2300 PLZL POLYUS PJSC 38.7000 RIGD RELIANCE INDUSTRIES 28.7000 RKMD ROSTELEKOM 6.9800 ROSN ROSNEFT OJSC 5.7920 SBER SBERBANK 18.6900 SGGD SURGUTNEFTEGAZ 5.2450 SMSN SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO 1148.0000 SSA SISTEMA JSFC 4.4200 SVST PAO SEVERSTAL 16.8200 TCS TCS GROUP HOLDING 19.3000 TMKS OAO TMK 5.4400 TRCN PJSC TRANSCONTAINER 8.0100 VTBR JSC VTB BANK 1.9370 Underlying code Underlying Name Expiration Price D7LKOD YEAR 17 DIVIDEND LUKOIL FUTURE 3.2643 YEAR 17 DIVIDEND MMC NORILSK NICKEL D7MNOD 1.8622 FUTURE D7OGZD YEAR 17 DIVIDEND GAZPROM FUTURE 0.2679 D7ROSN YEAR 17 DIVIDEND ROSNEFT FUTURE 0.1672 D7SBER YEAR 17 DIVIDEND SBERBANK FUTURE 0.3980 D7SGGD YEAR 17 DIVIDEND SURGUTNEFTEGAZ FUTURE 0.1000 D7VTBR YEAR 17 DIVIDEND VTB BANK FUTURE 0.0414 Members are asked to note that reports showing exercise/assignments should be available by approx. -

FY2020 Financial Results

Norilsk Nickel 2020 Financial Results Presentation February 2021 Disclaimer The information contained herein has been prepared using information available to PJSC MMC Norilsk Nickel (“Norilsk Nickel” or “Nornickel” or “NN”) at the time of preparation of the presentation. External or other factors may have impacted on the business of Norilsk Nickel and the content of this presentation, since its preparation. In addition all relevant information about Norilsk Nickel may not be included in this presentation. No representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information. Any forward looking information herein has been prepared on the basis of a number of assumptions which may prove to be incorrect. Forward looking statements, by the nature, involve risk and uncertainty and Norilsk Nickel cautions that actual results may differ materially from those expressed or implied in such statements. Reference should be made to the most recent Annual Report for a description of major risk factors. There may be other factors, both known and unknown to Norilsk Nickel, which may have an impact on its performance. This presentation should not be relied upon as a recommendation or forecast by Norilsk Nickel. Norilsk Nickel does not undertake an obligation to release any revision to the statements contained in this presentation. The information contained in this presentation shall not be deemed to be any form of commitment on the part of Norilsk Nickel in relation to any matters contained, or referred to, in this presentation. Norilsk Nickel expressly disclaims any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the contents of this presentation. -

Energy Without Borders

2011 GENERATING ASSETS 27 THERMAL POWER PLANTS, 2 HYDROPOWER PLANTS AND 1 WIND FARM IN THE MANAGEMENT INSTALLED CAPACITY 28.2 GW (+45.8%) SHARE IN THE TOTAL INSTALLED CAPACITY OF RUSSIA 10.2% GENERATION OF ELECTRIC POWER 116.9BN KW*H (+37.3%) BOILER HEAT THERMAL POWER 19.8M GCAL (+0.5%) POWER SUPPLY ASSETS ENERGY POWER SUPPLY ASSETS ENERGY SALES VOLUME AT THE RETAIL MARKET 143.1BN KW*H (SHARE AT THE RF MARKET 14.02%) POWER GRID ASSETS TOTAL LENGTH OF POWER TRANSMISSION LINES ABROAD 34265 KM (+1.1%) ELECTRICITY EXPORT AND IMPORT EXPORT VOLUME 22.7BN KW*H (+21.9%) (INCLUDING AZERBAIJAN +148.1% BELARUS +10774.7% GEORGIA +111.2% KAZAKHSTAN +60.5% CHINA +26.0% LITHUANIA +8.6% MONGOLIA +23.2% SOUTH OSSETIA +11.7% IMPORT VOLUME +17.2% (INCLUDING AZERBAIJAN +93.2% KAZAKHSTAN +58.0%) FINANCIAL INDICATORS REVENUE 536.2BN RUB (+15.5%) EBITDA 41.7BN RUB (+24.1%) NET PROFIT 41.5BN RUB (+123.1%) CAPITAL EXPENDITURES 32.5BN RUB (+97.0%) TOTAL ASSETS 531.9BN RUB (+113.5%) TOTAL EQUITY 390.7BN RUB (+180.9%) NUMBER OF PERSONNEL AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2011 47014 PERSONS ENERGY WITHOUT BORDERS ANNUAL REPORT 2011 JSC “INTER RAO UES” Contents ENERGY WITHOUT BORDERS.........................................................................................................................................................1 ADDRESS BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND THE CHAIRMAN OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD OF JSC “INTER RAO UES”..............................................................................................................8 1. General Information about the Company and its Place in the Industry...........................................................10 1.1. Brief History of the Company......................................................................................................................... 10 1.2. Business Model of the Group..........................................................................................................................12 1.4. -

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the Registrar of the Company and the Acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel

Information on IRC – R.O.S.T., the registrar of the Company and the acting Ballot Committee of MMC Norilsk Nickel IRC – R.O.S.T. (former R.O.S.T. Registrar merged with Independent Registrar Company in February 2019) was established in 1996. In 2003–2015, Independent Registrar Company was a member of Computershare Group, a global leader in registrar and transfer agency services. In July 2015, IRC changed its ownership to pass into the control of a group of independent Russian investors. In December 2016, R.O.S.T. Registrar and Independent Registrar Company, both owned by the same group of independent investors, formed IRC – R.O.S.T. Group of Companies. In 2018, Saint Petersburg Central Registrar joined the Group. In February 2019, Independent Registrar Company merged with IRC – R.O.S.T. Ultimate beneficiaries of IRC – R.O.S.T. Group are individuals with a strong background in business management and stock markets. No beneficiary holds a blocking stake in the Group. In accordance with indefinite License No. 045-13976-000001, IRC – R.O.S.T. keeps records of holders of registered securities. Services offered by IRC – R.O.S.T. to its clients include: › Records of shareholders, interestholders, bondholders, holders of mortgage participation certificates, lenders, and joint property owners › Meetings of shareholders, joint owners, lenders, company members, etc. › Electronic voting › Postal and electronic mailing › Corporate consulting › Buyback of securities, including payments for securities repurchased › Proxy solicitation › Call centre services › Depositary and brokerage, including escrow agent services IRC – R.O.S.T. Group invests a lot in development of proprietary high-tech solutions, e.g. -

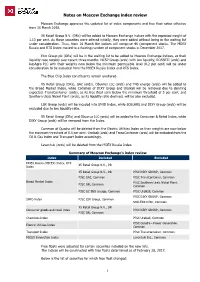

Notes on Moscow Exchange Index Review

Notes on Moscow Exchange index review Moscow Exchange approves the updated list of index components and free float ratios effective from 16 March 2018. X5 Retail Group N.V. (DRs) will be added to Moscow Exchange indices with the expected weight of 1.13 per cent. As these securities were offered initially, they were added without being in the waiting list under consideration. Thus, from 16 March the indices will comprise 46 (component stocks. The MOEX Russia and RTS Index moved to a floating number of component stocks in December 2017. En+ Group plc (DRs) will be in the waiting list to be added to Moscow Exchange indices, as their liquidity rose notably over recent three months. NCSP Group (ords) with low liquidity, ROSSETI (ords) and RosAgro PLC with their weights now below the minimum permissible level (0.2 per cent) will be under consideration to be excluded from the MOEX Russia Index and RTS Index. The Blue Chip Index constituents remain unaltered. X5 Retail Group (DRs), GAZ (ords), Obuvrus LLC (ords) and TNS energo (ords) will be added to the Broad Market Index, while Common of DIXY Group and Uralkali will be removed due to delisting expected. TransContainer (ords), as its free float sank below the minimum threshold of 5 per cent, and Southern Urals Nickel Plant (ords), as its liquidity ratio declined, will be also excluded. LSR Group (ords) will be incuded into SMID Index, while SOLLERS and DIXY Group (ords) will be excluded due to low liquidity ratio. X5 Retail Group (DRs) and Obuvrus LLC (ords) will be added to the Consumer & Retail Index, while DIXY Group (ords) will be removed from the Index. -

An Overview of Boards of Directors at Russia's Largest Public Companies

An Overview Of Boards Of Directors At Russia’s Largest Public Companies Andrei Rakitin Milena Barsukova Arina Mazunova Translated from Russian August 2020 Key Results According to information disclosed by 109 of Russia’s largest public companies: “Classic” board compositions of 11, nine, and seven seats prevail The total number of persons on Boards of the companies under study is not as low as it might seem: 89% of all Directors were elected to only one such Board Female Directors account for 12% and are more often elected to the audit, nomination, and remuneration committees than to the strategy committee Among Directors, there are more “humanitarians” than “techies,” while the share of “techies” among chairs is greater than across the whole sample The average age for Directors is 53, 56 for Chairmen, and 58 for Independent Directors Generation X is the most visible on Boards, and Generation Y Directors will likely quickly increase their presence if the impetuous development of digital technologies continues The share of Independent Directors barely reaches 30%, and there is an obvious lack of independence on key committees such as audit Senior Independent Directors were elected at 17% of the companies, while 89% of Chairs are not independent The average total remuneration paid to the Board of Directors is RUR 69 million, with the difference between the maximum and minimum being 18 times Twenty-four percent of the companies disclosed information on individual payments made to their Directors. According to this, the average total remuneration is approximately RUR 9 million per annum for a Director, RUR 17 million for a Chair, and RUR 11 million for an Independent Director The comparison of 2020 findings with results of a similar study published in 2012 paints an interesting dynamic picture. -

PRESS RELEASE JSC ALROSA Announces Purchase of a 25

PRESS RELEASE JSC ALROSA Announces Purchase of a 25 Percent Interest in OJSC Polyus Gold August, 2007, Moscow. Joint-Stock Company ALROSA signed an agreement with ONEXIM Group to buy a 25 percent stake in the Open Joint-Stock Company Polyus Gold (RTS, MICEX, and LSE – PLZL), Russia’s largest gold producer. “This deal was implemented as part of the development strategy approved by the Supervisory Board of JSC ALROSA. Among other things, ALROSA focuses on diversifying into other sectors. The purchase of a significant stake in Polyus Gold, which pursues an effective production strategy, will enable ALROSA to access a market with considerable long-term prospects and will further boost the development and economic growth of regions in Central and Eastern Siberia,” said President of ALROSA Sergei Vybornov. Open Joint-Stock Company Polyus Gold (RTS, MICEX, and LSE – PLZL) – is the leading gold producer in Russia and one of the biggest players in gold mining in the world in terms of deposits and production. The asset portfolio of Polyus Gold includes ore and alluvial gold deposits in the Krasnoyarsk Territory, the Irkutsk, Magadan, and Amur regions, and in the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia), where the company operates gold exploration and mining projects. As of January 1, 2007, the mineral resource base of OJSC Polyus Gold comprises 3,000.7 tons of gold in B+C1+C2 reserves, including 2,149 tons of B+C1 reserves. Joint-Stock Company ALROSA – is a global leader in diamond exploration, mining and sales of rough diamonds, and in cut diamond manufacture. ALROSA accounts for 97 percent of Russia’s rough diamond production and for 25 percent of the global output of rough diamonds. -

Telenor Mobile Communications AS V. Storm LLC

07-4974-cv(L); 08-6184-cv(CON); 08-6188-cv(CON) Telenor Mobile Communications AS v. Storm LLC Lynch, J. S.D.N.Y. 07-cv-6929 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT SUMMARY ORDER RULINGS BY SUMMARY ORDER DO NOT HAVE PRECEDENTIAL EFFECT. CITATION TO SUMMARY ORDERS FILED AFTER JANUARY 1, 2007, IS PERMITTED AND IS GOVERNED BY THIS COURT’S LOCAL RULE 32.1 AND FEDERAL RULE OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE 32.1. IN A BRIEF OR OTHER PAPER IN WHICH A LITIGANT CITES A SUMMARY ORDER, IN EACH PARAGRAPH IN WHICH A CITATION APPEARS, AT LEAST ONE CITATION MUST EITHER BE TO THE FEDERAL APPENDIX OR BE ACCOMPANIED BY THE NOTATION: (SUMMARY ORDER). A PARTY CITING A SUMMARY ORDER MUST SERVE A COPY OF THAT SUMMARY ORDER TOGETHER WITH THE PAPER IN WHICH THE SUMMARY ORDER IS CITED ON ANY PARTY NOT REPRESENTED BY COUNSEL UNLESS THE SUMMARY ORDER IS AVAILABLE IN AN ELECTRONIC DATABASE WHICH IS PUBLICLY ACCESSIBLE WITHOUT PAYMENT OF FEE (SUCH AS THE DATABASE AVAILABLE AT HTTP://WWW.CA2.USCOURTS.GOV/). IF NO COPY IS SERVED BY REASON OF THE AVAILABILITY OF THE ORDER ON SUCH A DATABASE, THE CITATION MUST INCLUDE REFERENCE TO THAT DATABASE AND THE DOCKET NUMBER OF THE CASE IN WHICH THE ORDER WAS ENTERED. 1 At a stated term of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, held at the 2 Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse, 500 Pearl Street, in the City of New York, on 3 the 8th day of October, two thousand nine, 4 5 PRESENT: 6 ROBERT D. -

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals After the Crisis: Results of 2011

Global Expansion of Russian Multinationals after the Crisis: Results of 2011 Report dated April 16, 2013 Moscow and New York, April 16, 2013 The Institute of World Economy and International Relations (IMEMO) of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, and the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment (VCC), a joint center of Columbia Law School and the Earth Institute at Columbia University in New York, are releasing the results of their third survey of Russian multinationals today.1 The survey, conducted from November 2012 to February 2013, is part of a long-term study of the global expansion of emerging market non-financial multinational enterprises (MNEs).2 The present report covers the period 2009-2011. Highlights Russia is one of the leading emerging markets in terms of outward foreign direct investments (FDI). Such a position is supported not by several multinational giants but by dozens of Russian MNEs in various industries. Foreign assets of the top 20 Russian non-financial MNEs grew every year covered by this report and reached US$ 111 billion at the end of 2011 (Table 1). Large Russian exporters usually use FDI in support of their foreign activities. As a result, oil and gas and steel companies with considerable exports are among the leading Russian MNEs. However, representatives of other industries also have significant foreign assets. Many companies remained “regional” MNEs. As a result, more than 66% of the ranked companies’ foreign assets were in Europe and Central Asia, with 28% in former republics of the Soviet Union (Annex table 2). Due to the popularity of off-shore jurisdictions to Russian MNEs, some Caribbean islands and Cyprus attracted many Russian subsidiaries with low levels of foreign assets. -

Press Release (PDF)

MECHEL REPORTS THE FY2020 FINANCIAL RESULTS Consolidated revenue – 265.5 bln rubles (-8% compared to FY 2019) EBITDA* – 41.1 bln rubles (-23% compared to FY 2019) Profit attributable to equity shareholders of Mechel PAO – 808 mln rubles Moscow, Russia – March 11, 2021 – Mechel PAO (MOEX: MTLR, NYSE: MTL), a leading Russian mining and steel group, announces financial results for the FY 2020. Mechel PAO’s Chief Executive Officer Oleg Korzhov commented: “The Group’s consolidated revenue in 2020 totaled 265.5 billion rubles, which is 8% less compared to 2019. EBITDA amounted to 41.1 billion rubles, which is 23% less year-on-year. “The mining division accounted for about 60% of the decrease in revenue. This was due to a significant decrease in coal prices year-on-year. In conditions of coronavirus limitations, many steelmakers around the world cut down on production, which could not fail to affect the demand for metallurgical coals and their price accordingly. By the year’s end the market demonstrated signs of a recovery, but due to China’s restrictions on Australian coal imports, coal prices outside on China remained low under this pressure. High prices in China have supported our mining division’s revenue to a certain extent. In 4Q2020 we increased shipments to China as best we could considering our long-term contractual obligations to partners from other countries. These circumstances became in many ways the reason for a decrease in our consolidated EBITDA. In Mechel’s other divisions EBITDA dynamics were positive year-on-year. “The decrease in the steel division’s revenue was also due to the coronavirus pandemic. -

Russian Games Market Report.Pdf

Foreword Following Newzoo’s free 42-page report on China and its games market, this report focuses on Russia. This report aims to provide understanding of the Russian market by putting it in a broader perspective. Russia is a dynamic and rapidly growing games We hope this helps to familiarize our clients and friends market, currently number 12 in the world in terms of around the globe with the intricacies of the Russian revenues generated. It is quickly becoming one of market. the most important players in the industry and its complexity warrants further attention and This report begins with some basic information on examination. The Russian market differs from its demographics, politics and cultural context, as well as European counterparts in many ways and this can be brief descriptions of the media, entertainment, telecoms traced to cultural and economic traditions, which in and internet sectors. It also contains short profiles of the some cases are comparable to their Asian key local players in these sectors, including the leading neighbours. local app stores, Search Engines and Social Networks. Russia has been a part of the Newzoo portfolio since In the second part of the report we move onto describe 2011, allowing us to witness first-hand the the games market in more detail, incorporating data unprecedented growth and potential within this from our own primary consumer research findings as market. We have accumulated a vast array of insights well as data from third party sources. on both the Russian consumers and the companies that are feeding this growth, allowing us to assist our clients with access to, and interpretation of, data on We also provide brief profiles of the top games in Russia, the Russia games market. -

Alfa Annual Report

ALFA GROUP CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AND REPORT OF THE AUDITORS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2001 STATEMENT OF MANAGEMENT’S RESPONSIBILITIES TO THE SHAREHOLDERS OF ALFA GROUP . International convention requires that Management prepare consolidated financial statements which give a true and fair view of the state of affairs of Alfa Group (“the Group”) at the end of each financial period and of the results, cash flows and changes in shareholders’ equity for each period. Management are responsible for ensuring that the Group keeps accounting records which disclose, with reasonable accuracy, the financial position of each entity and which enable it to ensure that the consoli- dated financial statements comply with International Accounting Standards and that their statutory accounting reports comply with the applicable country’s laws and regulations. Furthermore, appropriate adjustments were made to such statutory accounts to present the accompanying consolidated financial statements in accordance with International Accounting Standards. Management also have a general responsibility for taking such steps as are reasonably possible to safeguard the assets of the Group and to prevent and detect fraud and other irregularities. Management considers that, in preparing the consolidated financial statements set out on pages to , the Group has used appropriate and consistently applied accounting policies, which are supported by reasonable and prudent judgments and estimates and that appropriate International Accounting Standards have been followed. For and on behalf of Management Nigel J. Robinson October ZAO PricewaterhouseCoopers Audit Kosmodamianskaya Nab. 52, Bld. 5 115054 Moscow Russia Telephone +7 (095) 967 6000 Facsimile +7 (095) 967 6001 REPORT OF THE AUDITORS TO THE SHAREHOLDERS OF ALFA GROUP .