Yokai Monsters at Large

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peonza. Revista De Literatura Infantil Y Juvenil. Núm. 110, Octubre 2014

# 110 Revista de Literatura InfantilPEONZA y Juvenil | Octubre 2014 | Precio 10 € La vuelta al mundo en 90 novelas gráficas # La vuelta al mundo en 90 novelas gráficas 110 Peonza para Rubén Pellejero Rubén PEONZA Ilustraciones de Emociones, experimentos, creatividad, imaginación… ¡Vaya jardín! Un plan lector con el que los más pequeños aprenderán, disfrutarán y se formarán como lectores ¡Y este jardín no es un jardín cualquiera! El Jardín de los Libros se compone de seis colecciones de lecturas y recursos destinados a la integración de padres, profesores y mediadores en el proceso de socialización de la lectura de los niños. ¿Y tú, con cuál te quedas? www.oxfordinfantil.es >> La vuelta al mundo en 90 novelas gráficas >> SUMARIO Aya de Yopougon PEONZA nº110 Costa de Marfil . 92 Revista de Literatura Infantil y Juvenil | Octubre 2014 Adiós, muchachos Emigrantes Cuba . 94 Australia . 48 El cuaderno rojo Egon Schiele Dinamarca . 96 Austria. 50 Ciudad de barro Miércoles Egipto . 98 Barrio . 52 La Chelita La teoría del grano de arena El Salvador . 100 Bélgica. 54 Laika Crónicas birmanas Espacio exterior . 102 Birmania . 56 El arte de volar Gorazde: Zona protegida España . 104 Asterios Polyp EDITORIAL Bosnia . 58 Estados Unidos . 106 Auge de la novela gráfica . 4 Tierra de historias La máquina de Efrén Brasil. 60 Etiopía . 108 El año del conejo Los Combates Cotidianos ARTÍCULOS Camboya. 62 Francia . 110 Una introducción al cómic español ¡Puta Guerra! Rebétiko. La mala hierba del siglo XXI Campo de batalla. 64 Grecia . 112 Yexus . 7 Maus: relato de un superviviente Groenlandia–Manhattan La novela gráfica o el cómic de autor Campo de concentración . -

I. Early Days Through 1960S A. Tezuka I. Series 1. Sunday A

I. Early days through 1960s a. Tezuka i. Series 1. Sunday a. Dr. Thrill (1959) b. Zero Man (1959) c. Captain Ken (1960-61) d. Shiroi Pilot (1961-62) e. Brave Dan (1962) f. Akuma no Oto (1963) g. The Amazing 3 (1965-66) h. The Vampires (1966-67) i. Dororo (1967-68) 2. Magazine a. W3 / The Amazing 3 (1965) i. Only six chapters ii. Assistants 1. Shotaro Ishinomori a. Sunday i. Tonkatsu-chan (1959) ii. Dynamic 3 (1959) iii. Kakedaze Dash (1960) iv. Sabu to Ichi Torimono Hikae (1966-68 / 68-72) v. Blue Zone (1968) vi. Yami no Kaze (1969) b. Magazine i. Cyborg 009 (1966, Shotaro Ishinomori) 1. 2nd series 2. Fujiko Fujio a. Penname of duo i. Hiroshi Fujimoto (Fujiko F. Fujio) ii. Moto Abiko (Fujiko Fujio A) b. Series i. Fujiko F. Fujio 1. Paaman (1967) 2. 21-emon (1968-69) 3. Ume-boshi no Denka (1969) ii. Fujiko Fujio A 1. Ninja Hattori-kun (1964-68) iii. Duo 1. Obake no Q-taro (1964-66) 3. Fujio Akatsuka a. Osomatsu-kun (1962-69) [Sunday] b. Mou Retsu Atarou (1967-70) [Sunday] c. Tensai Bakabon (1969-70) [Magazine] d. Akatsuka Gag Shotaiseki (1969-70) [Jump] b. Magazine i. Tetsuya Chiba 1. Chikai no Makyu (1961-62, Kazuya Fukumoto [story] / Chiba [art]) 2. Ashita no Joe (1968-72, Ikki Kajiwara [story] / Chiba [art]) ii. Former rental magazine artists 1. Sanpei Shirato, best known for Legend of Kamui 2. Takao Saito, best known for Golgo 13 3. Shigeru Mizuki a. GeGeGe no Kitaro (1959) c. Other notable mangaka i. -

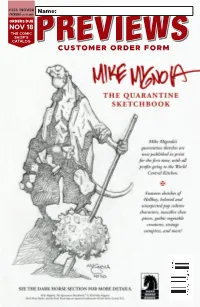

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. -

Japanese Animation and Glocalization of Sociology1 Kiyomitsu YUI Kobe University

44 SOCIOLOGISK FORSKNING 2010 Japanese Animation and Glocalization of Sociology1 Kiyomitsu YUI Kobe University Globalization of Japanese Comics and Animations Barcelona, Innsbruck, Seoul, Paris, Durban (South Africa), Beijing, Cairo, Krakow, Trento…, these are the cities where I have delivered my talks about Japanese anima- tion (Anime) and comics (Manga). Especially through the enthusiasm of the young audience of the classes which had nothing to do with whether my presentation was good or not, I have been impressed by the actuality of globalization. There are at least three reasons to pick Japanese animation and Manga up in so- ciology as its subject matter. First, pluralization of centers (“origins of dispatch”) of globalization. Second, globalization of culture and consciousness. Third, relationship between post-modern social settings and sub-cultures (cultural production). Talking first about the second point, globalization of culture: “Characters” in Manga and Anime can be considered as a sort of “icons” in the sense suggested by J. Alexander (Alexander, 2008:a, 2008:b). Icons are “condensed” symbols in the Freudian meaning (Alexander 2008:782). According to T. Parsons (alas, in the good old days we used to have “main stream” so to speak, and nowadays we have the cliché that goes “contrary to Parsons I argue…,” instead of “according to Parsons”), there are three aspects in culture as a symbolic system: cognitive, affective-expressive, and evaluative orientations. In Parsons’ age, globalization was not such a significant issue in sociology as in the present. Now we can set the new question: which aspect of a cultural symbol can be most feasible to be globalized, to be able to travel easily in the world? It would be unthinkable or at least very difficult to imagine a situation in which we would share the evaluative aspect such as a religious, moral or ideological orientation globally. -

Breathing New Life Into Comic Collections

BREATHING NEW LIFE INTO COMIC COLLECTIONS: DRAWN & QUARTERLY’S CHOICE TO REFORMAT & REPUBLISH FOR A YOUNG READERSHIP by Gillian Cott B.A. (Honours) English Language & Literature, University of Windsor, 2012 B.Ed., University of Windsor, 2013 Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Publishing Faculty of Communication, Art, and Technology © Gillian Cott, 2016 Simon Fraser University Fall 2016 • This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. APPROVAL Name Gillian Cott Degree Master of Publishing Title of Project Breathing New Life into Comic Collections: Drawn & Quarterly’s Choice to Reformat & Republish for a Young Readership Supervisory Committee ________________________________ Hannah McGregor Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor, Publishing Program Simon Fraser University ________________________________ John Maxwell Supervisor Associate Professor, Publishing Program Simon Fraser University ________________________________ Marcela Huerta Industry Supervisor Assistant Editor Drawn & Quarterly Montreal, Quebec Date Approved ________________________________ ii BREATHING NEW LIFE INTO COMIC COLLECTIONS ABSTRACT Graphic novels and comic reprints have recently surged in popularity due to Hollywood adaptations and bestselling titles such as Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis. Despite these successes, publishers still struggle to find the right audience for many comic collections. This report focuses on Drawn & Quarterly’s decision to reprint two comic collections in smaller, kid-friendly editions. It analyzes why D+Q decided to reformat the Janssons’ Moomin comics and Mizuki’s Kitaro manga for specific readerships, with a focus on the emerging genre of crossover literature. -

Une Sélection Des Bibliothécaires De Toulon

© Shigeru Mizuki / Production. All rights reserved. Édition Française : Cornélius 2007 MANGAS UNE SÉLECTION DES BIBLIOTHÉCAIRES DE TOULON BIBLIOTHÈQUE DU CENTRE VILLE 113 bd du Maréchal Leclerc Tél. : 04 94 36 81 20 Mardi, jeudi, vendredi : 13 h à 18 h Mercredi et samedi : 10 h à 18 h BIBLIOTHÈQUE DU STADE NAUTIQUE Av. de l’Armée d’Afrique Tél. : 04 94 36 33 35 Mardi et mercredi : 10 h à 18 h Jeudi et vendredi : 15 h à 18 h MÉDIATHÈQUE DE LA ROSERAIE Centre Municipal de la Roseraie Bd de la Roseraie Tél. : 04 98 00 13 30 Mardi et jeudi : 15 h à 18 h Mercredi et vendredi : 10 h à 18 h Samedi : 10 h à 14 h MÉDIATHÈQUE DU PONT DU LAS 447 av. du 15e Corps Section jeunesse : 04 94 36 36 52 Section adultes : 04 94 36 36 53 Espace Exposition : 04 94 36 36 59 Mardi et mercredi : 10 h à 18 h Vendredi : 15 h à 18 h Samedi : 10 h à 16 h 30 N° ISBN : 2-905076-66-6 © 2005 Guy Delcourt productions. Joann Sar REMERCIEMENTS • à Bruno Suzanna et à l’association Équinoxe • à Martine Larrivé, Médiathèque des 7 Mares (Élancourt, 78) • au service formation de la SFL • aux maisons d’éditions citées pour leurs autorisations de reproduction, en particulier les Éditions Cornélius Conception graphique et réalisation - Studio MCB 04 94 14 16 85 Impression - Imprimerie Marim Attention ! cette bibliographie est publiée dans le sens de lecture japonais, elle se lit de droite à gauche. Vous êtes donc ici à la fin ! 25 INDEX ALPHABÉTIQUES MANGAKAS ARAI Hideki 8 OBA Tsugumi 10 AZUMA Hideo 8 OTOMO Katsuhiro 10, 20, 22 EBINE Yamaji 8 SAKUISHI Harold 10 FUKUMOTO Nobuyuki -

![(Showa: a History of Japan) by Shigeru Mizuki [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3532/showa-a-history-of-japan-by-shigeru-mizuki-pdf-1793532.webp)

(Showa: a History of Japan) by Shigeru Mizuki [Pdf]

Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan (Showa: A History of Japan) by Shigeru Mizuki Ebook Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan (Showa: A History of Japan) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan (Showa: A History of Japan) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series: Showa: A History of Japan (Book 3) Paperback: 552 pages Publisher: Drawn and Quarterly (September 29, 2015) Language: English ISBN-10: 9781770462014 ISBN-13: 978-1770462014 ASIN: 1770462015 Product Dimensions:6.4 x 2.2 x 8.9 inches ISBN10 9781770462014 ISBN13 978-1770462 Download here >> Description: The final volume in the Eisner-nominated history of Japan; one of NPRs Best Books of 2014!Showa 1953-1989: A History of Japan concludes Shigeru Mizukis dazzling autobiographical and historical account of Showa-period Japan, a portrait both intimate and ranging of a defining epoch. The final volume picks up in the wake of Japans utter defeat in World War II, as a country reduced to rubble struggles to rise again. The Korean War brings new opportunities to a nation searching for an identity.A former enemy becomes their greatest ally as the United States funnels money, jobs, and opportunity into Japan, hoping to establish the country as a bulwark against Soviet Communist expansion. Japan reinvents itself, emerging as an economic powerhouse. Events like the Tokyo Olympiad and the Worlds Fair introduce a friendlier Japan to the world, but this period of peace and plenty conceals a populace still struggling to come to terms with the devastation of World War II.During this period of recovery and reconciliation, Mizukis struggles mirror those of the nation. -

The Dissemination and Localization of Anime in China: Case Study on the Chinese Mobile Video Game Onmyoji

The dissemination and localization of anime in China: Case study on the Chinese mobile video game Onmyoji Wuqian Qian The Department of Asian, Middle Eastern and Turkish Studies Master Program in Asian Studies, 120 hp Autumn term 2016 Supervisor: Jaqueline Berndt English title: Professor Abstract In the 2017 Chinese Gaming Industry Report, a new type of video games called 二次 元 game is noted as a growing force in the game industry. Onmyoji is one of those games produced by Netease and highly popular with over 200 million registered players in China alone. 二次元 games are characterized by Japanese-language dubbing and anime style in character design. However, Onmyoji uses also Japanese folklore, which raises two questions: one is why Netease chose to make such a 二次元 game, the other why a Chinese game using Japanese folklore is so popular among Chinese players. The attractiveness of an exotic culture may help to explain the latter, but it does not work for the first. Thus, this thesis implements a media studies perspective in order to substantiate its hypothesis that it is the dissemination of anime in China that has made Onmyoji possible and successful. Unlike critics who regard anime as an imported product from Japan which is different from domestic Chinese animation and impairs its development, this study pays attention to the interrelation between media platforms and viewer (or user) demographics, and it explores the positive influence of Japanese anime on the Chinese creative industry, implying the feasibility of anime or 二次元 products to be created in other countries than Japan. -

1 the Cool Japan Project and the Globalization of Anime

THE COOL JAPAN PROJECT AND THE GLOBALIZATION OF ANIME AND MANGA IN THE UNITED STATES by Joshua Michael Draper Honors Thesis Appalachian State University Submitted to the Department of Cultural, Gender, and Global Studies and The Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts May, 2015 Approved by: Wei Xie, Ph.D., Thesis Director Alexandra Sterling-Hellenbrand, Ph.D., Second Reader Jeanne Dubino, Ph.D., Department Honors Director Leslie Sargent Jones, Ph.D., Director, The Honors College 1 The Cool Japan Project and the Globalization of Anime and Manga in the United States Abstract: This research paper will primarily discuss the impact that Japanese animation and manga have had on American popular culture and the subsequent cult following they developed. It will discuss what distinguishes Japanese animation from Western animation, how Japanese animation initially gained popularity among American audiences, and how it has subsequently impacted American popular culture. This paper will also focus on the subculture of otaku, a group of people known for their devoted following to Japanese animation and comic books. The purpose of this paper is to discuss the relative popularity of Japanese animation and manga amongst American audiences as an example of globalization impacting the United States from another country. Keywords: anime, manga, soft power, Cool Japan, globalization 2 Introduction During the 1980s and 1990s, Japanese animation and comic books began coming overseas to the United States, where it soon gained popularity amongst a sizeable number of young Americans. Recognizing the economic potential of Japanese popular culture, in 2002, Douglas McGray, writing for Foreign Policy, wrote an article titled “Japan’s Gross National Cool”, highlighting Japan’s potential to be a global “soft power”, or a country that promotes itself through its cultural influence rather than by economic and military force. -

Transcultural Otaku: Japanese Representations of Fandom and Representations of Japan in Anime/Manga Fan Cultures

Transcultural otaku: Japanese representations of fandom and representations of Japan in anime/manga fan cultures Matt Hills, Cardiff University “Otaku is a Japanese word coined during the eighties, it is used to describe fanatics that have an obsessive interest or hobby... The Japanese think of otaku the same way most people think of nerds - sad and socially inept. Western Anime fans often use the word to describe anime and manga fans, except with more enthusiastic tones than the Japanese.” (http://www.thip.co.uk/work/Competition2/what.htm#otaku) This paper will consider the transcultural appropriation of Japanese representations of fandom. The Japanese term “otaku” is similar to pathologising representations of media fandom in the US and UK (where fans are stereotyped as geeks: see Jensen 1992). Although writers dealing with Western fans of Japanese anime and manga have noted these fans’ positive revaluation of the term “otaku” (Schodt 1996 and Mecallado 2000), such writers have not considered this transcultural ‘(mis)reading’ in sufficient detail (Palumbo- Liu and Ulrich Gumbrecht 1997; An 2001). And it should be noted from the outset that by placing misreading in scare quotes, I want to express certain misgivings about this mis-concept. The US/UK appropriation of a (negative) fan stereotype from a different national context raises a number of questions. Firstly, although fans have long been viewed as active, appropriating audiences (Jenkins 1992), this process of appropriation has been largely explored via the relationship between fans and their favoured texts rather than between fans and “foreign” representations of fandom. Discussions of fandom have been typically severed from discussions of national identity, often by virtue of the fact that certain “traditional” fan objects and their US/UK audiences (Napier 2001:256, referring to Star Trek and Star Wars, and we might add Doctor Who) have provided an object of study for scholars placed within the same “national contexts” as the fan cultures they are analysing. -

“Rotten Culture”: from Japan to China MASTER of ARTS

“Rotten Culture”: from Japan to China by Nishang Li Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 2016 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Pacific and Asian Studies Nishang Li, 2019 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. Thesis: “Rotten Culture” from Japan to China by Nishang Li Bachelor of Arts, University of Victoria, 2016 Supervisory Committee Dr. Michael Bodden, Supervisor Department of Pacific and Asian Studies Dr. Richard King, Department Member Department of Pacific and Asian Studies ii Abstract A new sub-culture, “Rotten Culture (腐文化) ”, evolved from Japanese Boys’ Love (BL) manga, has rapidly spread in China and dramatically influenced many areas of Chinese artistic creation. “Rotten Culture” is an extension of Boys’ Love, which indicates that Boys’ Love elements not only existed in manga, but emerged in anime, movies, TV series, and so on. As a start of an analysis of this phenomenon, this thesis will focus on the core of “Rotten Culture”, Boys’ Love, which exists in Chinese manga and web fiction. The central issues addressed by this thesis are: exploring the circulation of Boys’ Love from Japan to China; examining the aesthetics and themes of some of these works; and analyzing the motivations that explain why such a huge amount of people, both professional and non-professional, have joined in creating Boys’ Love art works. iii -

Local Japan: Case Studies in Place Promotion Manga and Anime Statues As Local Landmarks

Local Japan: Case Studies in Place Promotion Manga and Anime statues as local landmarks Among Japan’s most popular exports of the past several decades are Japanese comics and cartoons, or manga and anime as they are better known. There is a current trend in Japanese cities with ties to manga and anime (either as the home of the author or the setting of the manga/anime itself) that has seen local governments and NPOs contributing to the construction (and promotion) of statues immortalising some of the most popular characters. While cartoonish mascots or Yurukyara are a mainstay of regional promotion in Japan, they usually appear as souvenirs, logos on local attractions and goods, or “in person” at events. On the other hand, “character monuments”, such as the ones explored below serve as more permanent fixtures within a region’s place promotion and identity. They also add another dimension to the ways in which local governments in Japan can capitalise on the spread of Japanese manga and anime as global cultural phenomena. Tetsujin 28-go, (Nagata Ward, Kobe) Nagata ward profile One of the nine wards of Kobe Population: 102,387 Area: 11.46km² Density: 8,580/ km² Kobe within Japan Nagata ward within Kobe Copyright © Hyogo Tourism Association Built in 2009 to commemorate the 15th anniversary of the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake of 1995, this 18 meter, 50 tonne steel statue commemorates the work of the late manga artist, Mitsuteru Yokoyama, a Kobe native. The statue itself embodies “Tetsujin 28-go” (Iron Man number 28), the eponymous hero of a serialised manga that ran from 1956.