Breathing New Life Into Comic Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peonza. Revista De Literatura Infantil Y Juvenil. Núm. 110, Octubre 2014

# 110 Revista de Literatura InfantilPEONZA y Juvenil | Octubre 2014 | Precio 10 € La vuelta al mundo en 90 novelas gráficas # La vuelta al mundo en 90 novelas gráficas 110 Peonza para Rubén Pellejero Rubén PEONZA Ilustraciones de Emociones, experimentos, creatividad, imaginación… ¡Vaya jardín! Un plan lector con el que los más pequeños aprenderán, disfrutarán y se formarán como lectores ¡Y este jardín no es un jardín cualquiera! El Jardín de los Libros se compone de seis colecciones de lecturas y recursos destinados a la integración de padres, profesores y mediadores en el proceso de socialización de la lectura de los niños. ¿Y tú, con cuál te quedas? www.oxfordinfantil.es >> La vuelta al mundo en 90 novelas gráficas >> SUMARIO Aya de Yopougon PEONZA nº110 Costa de Marfil . 92 Revista de Literatura Infantil y Juvenil | Octubre 2014 Adiós, muchachos Emigrantes Cuba . 94 Australia . 48 El cuaderno rojo Egon Schiele Dinamarca . 96 Austria. 50 Ciudad de barro Miércoles Egipto . 98 Barrio . 52 La Chelita La teoría del grano de arena El Salvador . 100 Bélgica. 54 Laika Crónicas birmanas Espacio exterior . 102 Birmania . 56 El arte de volar Gorazde: Zona protegida España . 104 Asterios Polyp EDITORIAL Bosnia . 58 Estados Unidos . 106 Auge de la novela gráfica . 4 Tierra de historias La máquina de Efrén Brasil. 60 Etiopía . 108 El año del conejo Los Combates Cotidianos ARTÍCULOS Camboya. 62 Francia . 110 Una introducción al cómic español ¡Puta Guerra! Rebétiko. La mala hierba del siglo XXI Campo de batalla. 64 Grecia . 112 Yexus . 7 Maus: relato de un superviviente Groenlandia–Manhattan La novela gráfica o el cómic de autor Campo de concentración . -

Stephen Colbert's Super PAC and the Growing Role of Comedy in Our

STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE BY MELISSA CHANG, SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS ADVISER: CHRIS EDELSON, PROFESSOR IN THE SCHOOL OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS UNIVERSITY HONORS IN CLEG SPRING 2012 Dedicated to Professor Chris Edelson for his generous support and encouragement, and to Professor Lauren Feldman who inspired my capstone with her course on “Entertainment, Comedy, and Politics”. Thank you so, so much! 2 | C h a n g STEPHEN COLBERT’S SUPER PAC AND THE GROWING ROLE OF COMEDY IN OUR POLITICAL DISCOURSE Abstract: Comedy plays an increasingly legitimate role in the American political discourse as figures such as Stephen Colbert effectively use humor and satire to scrutinize politics and current events, and encourage the public to think more critically about how our government and leaders rule. In his response to the Supreme Court case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) and the rise of Super PACs, Stephen Colbert has taken the lead in critiquing changes in campaign finance. This study analyzes segments from The Colbert Report and the Colbert Super PAC, identifying his message and tactics. This paper aims to demonstrate how Colbert pushes political satire to new heights by engaging in real life campaigns, thereby offering a legitimate voice in today’s political discourse. INTRODUCTION While political satire is not new, few have mastered this art like Stephen Colbert, whose originality and influence have catapulted him to the status of a pop culture icon. Never breaking character from his zany, blustering persona, Colbert has transformed the way Americans view politics by using comedy to draw attention to important issues of the day, critiquing and unpacking these issues in a digestible way for a wide audience. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Manga Book Club Handbook

MANGA BOOK CLUB HANDBOOK Starting and making the most of book clubs for manga! STAFF COMIC Director’sBOOK LEGAL Note Charles Brownstein, Executive Director DEFENSE FUND Alex Cox, Deputy Director Everything is changing in 2016, yet the familiar challenges of the past continueBetsy to Gomez, Editorial Director reverberate with great force. This isn’t just true in the broader world, but in comics,Maren Williams, Contributing Editor Comic Book Legal Defense Fund is a non-profit organization Caitlin McCabe, Contributing Editor too. While the boundaries defining representation and content in free expression are protectingexpanding, wethe continue freedom to see to biasedread comics!or outmoded Our viewpoints work protects stifling those advances.Robert Corn-Revere, Legal Counsel readers, creators, librarians, retailers, publishers, and educa- STAFF As you’ll see in this issue of CBLDF Defender, we are working on both ends of the Charles Brownstein, Executive Director torsspectrum who byface providing the threat vital educationof censorship. about the We people monitor whose worklegislation expanded free exBOARD- Alex OF Cox, DIRECTORS Deputy Director pression while simultaneously fighting all attempts to censor creative work in comics.Larry Marder,Betsy Gomez, President Editorial Director and challenge laws that would limit the First Amendment. Maren Williams, Contributing Editor In this issue, we work the former end of the spectrum with a pair of articles spotlightMilton- Griepp, Vice President We create resources that promote understanding of com- Jeff Abraham,Caitlin McCabe,Treasurer Contributing Editor ing the pioneers who advanced diverse content. On page 10, “Profiles in Black Cartoon- Dale Cendali,Robert SecretaryCorn-Revere, Legal Counsel icsing” and introduces the rights you toour some community of the cartoonists is guaranteed. -

Developing Kamishibai (Japanese Card-Story) Media in Teaching Speaking

4rd English Language and Literature International Conference (ELLiC) Electronic ISSN: 2579-7263 Proceedings – (ELLiC Proceedings Vol. 4, 2021) CD-ROM ISSN: 2579-7549 DEVELOPING KAMISHIBAI (JAPANESE CARD-STORY) MEDIA IN TEACHING SPEAKING Yuli Puji Astutik1, Riski Mulyana2 STIT Muhammadiyah Tanjung Redeb Indonesia [email protected], [email protected] Abstract This study aims at developing and testing the feasibility of Kamishibai media as a learning medium by modifying a story adapted from Berau Folklore East Kalimantan. The research method used in this research was Research and Development (R&D) by adapting ADDIE Model of development which covered several steps namely: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation. The result of this research was a learning media namely Kamishibai by modifying it with the story of Berau folklore East Kalimantan. Based on the result of media experts’ validation, it showed that the response was 100%, while the result of material and language quality was 93%. It can be summarized that the developed media can be categorized as “Decent” or suitable to be used as a learning media. Meanwhile, the result of students’ responses towards the media developed was 81.13%. it can be considered positive of the media of Kamishibai (Japanese-Card Story) was feasible and suitable to be applicated as the learning media in speaking. Keywords: Research & Development (R&D), Kamishibai Media, ADDIE Model Introduction Language is considered vital for human learning English as a foreign language, communication. It is a crucial element of people can engage in international education which can be used as a tool in commerce, advance in their studies, and expressing ideas, thoughts, feelings and participate in scientific activities. -

Kamishibai, What Is It? Some Preliminary Findings

1 KAMISHIBAI, WHAT IS IT? SOME PRELIMINARY FINDINGS Jeffrey A. Dym From January to May 2007, I spent time researching the history of kamishibai in Japan. Prior to leaving, when my colleagues asked me what I was researching, I would reply kamishibai. Of course, they had no idea what I was talking about. When you tell someone in Japan you are studying kamishibai, they might look at you with a puzzled look, wondering why you are studying that and not something more practical and business oriented but at least they know what you are talking about. For most Americans, the subject is completely arcane. The usual translation of kamishibai is “paper plays.” But I found that telling my colleagues that I was studying paper plays really didn’t clarify things. It often conjured up for them an image of Indonesian puppet theater. Instead, I usually resorted to telling them that I was studying a type of street performance that was popular in Japan during the 1930s and 1950s. Indeed, it is possible to offer a fairly straightforward description of kamishibai. Kamishibai, in a format similar to the ones presented on Kamishibai for Kids, first appeared in 1930 in Tokyo and quickly became one of the most popular forms of mass entertainment in the major cities of Japan. Kamishibai is designed so that virtually anyone can perform it. Though the first kamishibai didn’t have words on the back, within a few years of its debut words were added to the back of the pictures so that anyone could perform it. -

I. Early Days Through 1960S A. Tezuka I. Series 1. Sunday A

I. Early days through 1960s a. Tezuka i. Series 1. Sunday a. Dr. Thrill (1959) b. Zero Man (1959) c. Captain Ken (1960-61) d. Shiroi Pilot (1961-62) e. Brave Dan (1962) f. Akuma no Oto (1963) g. The Amazing 3 (1965-66) h. The Vampires (1966-67) i. Dororo (1967-68) 2. Magazine a. W3 / The Amazing 3 (1965) i. Only six chapters ii. Assistants 1. Shotaro Ishinomori a. Sunday i. Tonkatsu-chan (1959) ii. Dynamic 3 (1959) iii. Kakedaze Dash (1960) iv. Sabu to Ichi Torimono Hikae (1966-68 / 68-72) v. Blue Zone (1968) vi. Yami no Kaze (1969) b. Magazine i. Cyborg 009 (1966, Shotaro Ishinomori) 1. 2nd series 2. Fujiko Fujio a. Penname of duo i. Hiroshi Fujimoto (Fujiko F. Fujio) ii. Moto Abiko (Fujiko Fujio A) b. Series i. Fujiko F. Fujio 1. Paaman (1967) 2. 21-emon (1968-69) 3. Ume-boshi no Denka (1969) ii. Fujiko Fujio A 1. Ninja Hattori-kun (1964-68) iii. Duo 1. Obake no Q-taro (1964-66) 3. Fujio Akatsuka a. Osomatsu-kun (1962-69) [Sunday] b. Mou Retsu Atarou (1967-70) [Sunday] c. Tensai Bakabon (1969-70) [Magazine] d. Akatsuka Gag Shotaiseki (1969-70) [Jump] b. Magazine i. Tetsuya Chiba 1. Chikai no Makyu (1961-62, Kazuya Fukumoto [story] / Chiba [art]) 2. Ashita no Joe (1968-72, Ikki Kajiwara [story] / Chiba [art]) ii. Former rental magazine artists 1. Sanpei Shirato, best known for Legend of Kamui 2. Takao Saito, best known for Golgo 13 3. Shigeru Mizuki a. GeGeGe no Kitaro (1959) c. Other notable mangaka i. -

Core Collections in Genre Studies Romance Fiction

the alert collector Neal Wyatt, Editor Building genre collections is a central concern of public li- brary collection development efforts. Even for college and Core Collections university libraries, where it is not a major focus, a solid core collection makes a welcome addition for students needing a break from their course load and supports a range of aca- in Genre Studies demic interests. Given the widespread popularity of genre books, understanding the basics of a given genre is a great skill for all types of librarians to have. Romance Fiction 101 It was, therefore, an important and groundbreaking event when the RUSA Collection Development and Evaluation Section (CODES) voted to create a new juried list highlight- ing the best in genre literature. The Reading List, as the new list will be called, honors the single best title in eight genre categories: romance, mystery, science fiction, fantasy, horror, historical fiction, women’s fiction, and the adrenaline genre group consisting of thriller, suspense, and adventure. To celebrate this new list and explore the wealth of genre literature, The Alert Collector will launch an ongoing, occa- Neal Wyatt and Georgine sional series of genre-themed articles. This column explores olson, kristin Ramsdell, Joyce the romance genre in all its many incarnations. Saricks, and Lynne Welch, Five librarians gathered together to write this column Guest Columnists and share their knowledge and love of the genre. Each was asked to write an introduction to a subgenre and to select five books that highlight the features of that subgenre. The result Correspondence concerning the is an enlightening, entertaining guide to building a core col- column should be addressed to Neal lection in the genre area that accounts for almost half of all Wyatt, Collection Management paperbacks sold each year.1 Manager, Chesterfield County Public Georgine Olson, who wrote the historical romance sec- Library, 9501 Lori Rd., Chesterfield, VA tion, has been reading historical romance even longer than 23832; [email protected]. -

S16-Macmillan-Children.Pdf

FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX (BYR) • MAY 2016 JUVENILE FICTION / ANIMALS / FISHES DEBORAH DIESEN; ILLUSTRATED BY DAN HANNA The PoutPout Fish Giant Sticker Book The star of the New York Times bestselling picture book The PoutPout Fish is back in this new sticker activity book with over 1,000 stickers! Preschoolers will love the funpacked pages of this ohso cute PoutPout Fish sticker book. Little hands will be kept busy using over 1,000 stickers featuring characters from the series to finish sticker scenes, solve mazes, and complete other puzzles. Perfect for rainy days inside or sunny days outside, car trips or at home, to share with friends or individual play, this sticker book is sure to MAY delight little guppies. Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR) Juvenile Fiction / Animals / Fishes On Sale 5/10/2016 Deborah Diesen currently works for a nonprofit Ages 3 to 5 organization and has also worked as a librarian and a Trade Paperback , 128 pages bookseller. She lives in Grand Ledge, Michigan. 8.5 in W | 11 in H deborahdiesen.com Carton Quantity: 24 ISBN: 9781250063946 $12.99 / $13.99 Can. Dan Hanna has over ten years of experience in the animation industry, and his work has appeared on the Cartoon Network. He lives in Oxnard, California. Also available danhanna.com Praise For... The PoutPout Fish series: The PoutPout Fish: Wipe Clean Workbook ABC, 1 20 "Winning artwork . Hanna's cartoonish undersea world 9781250061959 swims with hilarious bugeyed creatures that ooze $12.99/$13.99 Can. personality." Kirkus Reviews LifttheFlap Tab: HideandSeek, PoutPout Fish 9781250060112 $8.99/$8.99 Can. -

Kamishibai: an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Japanese Culture and Its Application in Infant Education

KÉPZÉS ÉS GYAKORLAT • 2017. 15. ÉVFOLYAM 1−2. SZÁM. DOI: 10.17165/TP.2017.1-2.2 ANA MARQUÉS IBÁÑEZ1 Kamishibai: An intangible cultural heritage of Japanese culture and its application in Infant Education In the field of art education, it is imperative to use new and innovative methods to study visual culture, and to adopt multicultural and intercultural approaches to interpret art in different cultures. It is interesting to study the way in which the intertextual method (the interrelationship between texts, whether written, oral, past or present; the implicit or explicit connection between a set of texts forming a context which conditions the understanding and development of the discourse) can be employed to interpret art from a western or eastern perspective. The kamishibai art form should be integrated into pre-school and elementary school curricula to promote reading. This proposal goes beyond simply understanding a text with images. The focus is on how a text can be performed theatrically and involve the participation and interaction of children as protagonists in the process. We start by introducing the concept of kamishibai, including its origins and different stages of evolution throughout history until the present day. Then, we discuss the potential new roles that contemporary kamishibai could assume in the educational context. Finally, we present an educational proposal to promote its use in early childhood education. We consider that the development of artistic interpretation, the potential value of a text when performed theatrically facilitates the introduction of multiculturalism to children. 1. Introduction Kamishibai is a type of theatrical performance that offers an alternative way to tell stories to children. -

Graphic Novels Plan

Automatically Yours™ from Baker & Taylor Automatically Yours™ Graphic Novels Plan utomatically YoursTM from Baker & Taylor is a Specialized Collection Program that delivers the latest publications from popular authors right to Ayour door, automatically. Automatically Yours offers a variety of plans to meet your library’s needs including: Popular Adult Fiction Authors, B&T Kids, Spokenword Audio, Popular Book Clubs and Graphic Novels. Our Graphic Novels Plan delivers the latest publications to your library, automatically. Choose the novels that are right for your library and we’ll do the rest. No more placing separate orders, no worrying about title availability - they’ll arrive on time at your library. A new feature of the Automatically Yours program is updated lists of forthcoming titles available on our website, www.btol.com. Click on the Public Tab, then choose Automatic Shipments and Automatically Yours to view the current lists. Sign-up today! Simply fill out the enclosed listing by indicating the number of copies you require, complete the Account Information Form and return them both to Baker & Taylor. It’s that simple! Questions? Call us at 800.775.1200 x2315 or visit www.btol.com Automatically Yours™ from Baker & Taylor Sign up by Vendor/Character, Author or Illustrator. Fill in the quantity you need for each selection, fill out the Account Information Form and we’ll do the rest. It’s that simple! * Vendor/Character Listing: AIT-Planet Lar: ____ Hellboy - Adult Fantagraphics: ____ ALL Titles - Teen ____ Lone Wolf and Cub - Adult ____ ALL Hardcover Titles - Adult ____ O My Goddess - All Ages ____ ALL Paperback Titles - Adult Alternative Comics: ____ Predator - Teen ____ ALL Titles - Adult G.T. -

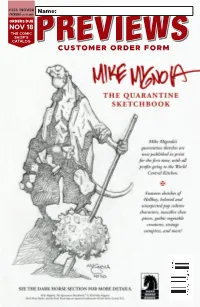

Customer Order Form

#386 | NOV20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE NOV 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Nov20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:23:12 AM Nov20 Ad DST Rogue.indd 1 10/8/2020 11:07:39 AM PREMIER COMICS HAHA #1 IMAGE COMICS 30 RAIN LIKE HAMMERS #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 CRIMSON FLOWER #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 62 AVATAR: THE NEXT SHADOW #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 64 MARVEL ACTION: CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING 104 KING IN BLACK: BLACK KNIGHT #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-6 RED SONJA: THE SUPER POWERS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 126 ABBOTT: 1973 #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 158 Nov20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 10/8/2020 8:24:32 AM COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS · PRINT Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE FEATURED ITEMS Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS I Breathed A Body #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY COMIC BOOKS · GRAPHIC NOVELS Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Gung-Ho: Sexy Beast #1 l ABLAZE Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC. Serial #1 l ABSTRACT STUDIOS 1 Delicates TP l ONI PRESS l I Breathed A Body #1 AFTERSHOCK COMICS 1 The Cutting Edge: Devil’s Mirror #1 l TITAN COMICS The Wrong Earth: Night and Day #1 l AHOY COMICS Knights of Heliopolis HC l TITAN COMICS The Three Stooges: Through the Ages #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Blade Runner 2029 #2 l TITAN COMICS Warrior Nun Dora Volume 1 TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars Insider #200 l TITAN COMICS Crumb’s World HC l DAVID ZWIRNER BOOKS Comic Book Creator #25 l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Tono Monogatari: Shigeru Mizuki Folklore GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Bloodshot #9 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Barry Windsor-Smith: Monsters HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Vagrant Queen Volume 2: A Planet Called Doom TP l VAULT COMICS Aster of Pan HC l MAGNETIC PRESS INC.