Assessment of Potential Financial Resources Technical Memorandum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Appendices

LAKE HOOD SEAPLANE BASE MASTER PLAN UPDATE Report Appendices September 2017 DOWL in conjunction with : RS&H, Southeast Strategies, and Solstice Advertising APPENDIX A Historical Photos of LHD THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK APPENDIX B Initial Survey Report THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY BLANK LAKE HOOD SEAPLANE BASE MASTER PLAN UPDATE User Survey Results April 2015 DOWL in conjunction with : RS&H, Southeast Strategies, and Solstice Advertising LAKE HOOD MASTER PLAN USER SURVEY RESULTS ANCHORAGE, ALASKA Prepared for: State of Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities Ted Stevens Anchorage International Airport P.O. Box 196960 Anchorage, Alaska 99519 Prepared by: DOWL 4041 B Street Anchorage, Alaska 99503 (907) 562-2000 AKSAS Number: 57737 April 2015 Lake Hood Master Plan Anchorage, Alaska User Survey Report April 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE ...............................................................................................1 WHO RESPONDED TO THE SURVEY .......................................................................................3 WHY DO YOU OPERATE FROM LHD .......................................................................................6 AIRCRAFT TYPES OPERATING OR POTENTIALLY OPERATING AT LHD .......................8 CAN/SHOULD LHD GROW .........................................................................................................9 INTEREST IN LEASING AND DEVELOPING AT LHD ..........................................................10 TYPE -

Airport Advisory Commission

City of Wasilla 290 E Herning Avenue, Wasilla, Alaska Commissioners Commissioners Noel Lowe Wasilla Airport Advisory Raymond Block Charles Morris Commission Adam Paulick, Chair John Popecki, Vice Chair Cameron Sharick Regular Meeting Agenda Michael Lucas www.cityofwasilla.com Meeting Date 907-373-9010 Location October 25, 2018 Council Chambers 6:00 p.m. Wasilla City Hall 290 E Herning Avenue Page 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. ROLL CALL 3. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE 4. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 5. APPROVAL OF MINUTES Regular Meeting Minutes: April 19, 2018 3 - 5 6. STAFF REPORTS 7. PUBLIC COMMENTS (THREE MINUTES PER PERSON) 8. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 9. NEW BUSINESS Wasilla Municipal Airport Construct Apron E Phase 1 10. PUBLIC COMMENTS (THREE MINUTES PER PERSON) 11. STAFF AND COMMISSION COMMENTS 12. ADJOURNMENT Airport Advisory Commission Meeting Packet - 10/25/18 Page 1 of 5 Page 2 of 5 WASILLA AIRPORT ADVISORY COMMISSION REGULAR MEETING MINUTES APRIL 19, 2018 COMMISSIONERS Noel Lowe PRESENT: John Popecki Raymond Block Adam Paulick Cameron Sharick Michael Lucas in at 6:05 PM COMMISSIONERS Charles Morris ABSENT: STAFF PRESENT: Archie Giddings, Public Works Director Jolene Cooper, Finance Clerk II Ashley Loyer, Commission Secretary 1. CALL TO ORDER The regular meeting of the Airport Advisory Commission was called to order at 6:00 p.m. on April 19, 2018, in Council Chambers of City Hall, Wasilla, Alaska by Chair Paulick. 2. ROLL CALL Upon roll call, a quorum of the Wasilla Airport Advisory Commission was established. 3. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Commissioner Paulick led the Pledge of Allegiance. 4. APPROVAL OF AGENDA The agenda was approved as presented without objection by unanimous consent. -

Public-Data File 88-21 GROUND-WATER-QUALITY

Public-data File 88-21 GROUND-WATER-QUALITY MONITORING NETWORKS IN ALASKA 1 Danita L. Maynard Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys July 1988 THIS REPORT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED FOR TECHNICAL CONTENT (EXCEPT AS NOTED IN TEXT) OR FOR CONFORMITY TO THE EDITORIAL STANDARDS OF DGGS. 794 University Avenue, Suite 200 Fairbanks, Alaska 99709-3645 'DGGS, 18225 Fish Hatchery Road, P.O. Box 772116, Eagle River, Alaska 99577. Table of Contents PAGE Introduction............................. 1 Northern Region Ambient Trend ~onitorik~ U.S. Geological Survey .................... 2 Site Monitoring U.S.DepartmentofDefense .................. 2 Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation........ 3 Alaska Department o'f Natural Resources ............ 6 University of Alaska ..................... 6 Public Water System (PWS) Monitoring Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation ........ 7 Alaska Department of Fish and Game .............. 16 Southcentral Region Ambient Trend Monitoring Alaska Department of Natural Resources ............ 18 Municipality of Anchorage .................. 18 Site Monitoring U.S. Department of Defense .................. 19 Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation ........ 20 Public Water System (PWS) ~onitoring Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation ........ 41 Alaska Department of Fish and Game .............. 64 Southeast Region Public Water System (PWS) Monitoring Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation ........ 66 CURRENT AND RECENT GROUND-WATER QUALITY MONITORING NETWORKS IN ALASKA INTRODUCTION This report contains data supplemental to Maynard (1988), an evaluation of ground-water quality monitoring in Alaska. Ground-water quality monitoring is necessary to assess trends in ground-water quality, detect or assess ground-water contamination, assess remediation efforts, and assure potability of public-water systems (PWS) using ground-water supplies. The monitoring networks included here are administered by federal, state, or local agencies within Alaska. -

E. Transportation and Public Transit West Anchorage District Plan

E. Transportation and Public Transit West Anchorage District Plan TRANSPORTATION The West Anchorage transportation system is comprised of surface road, railroad, aviation, public transit, and nonmotorized (pedestrian, bicycle, and trail) facilities. Other components of Anchorage’s transportation system include freight distribution, regional connections, and congestion management (MOA, 2005). Inter-Bowl travel is dominated by personal vehicles on the surface road network, but this chapter will discuss the current state of all elements of West Anchorage’s transportation system and its associated facilities. Relationship to Other Transportation Plans Anchorage Metropolitan Area Transportation Solutions (AMATS) is the federally designated metropolitan planning organization responsible for transportation planning in the entire Municipality. The Anchorage Bowl 2025 Long-Range Transportation Plan (LRTP) with 2027 Revisions (MOA, 2005) was developed through the AMATS planning process and is used to identify current and future system deficiencies that need improvement to meet MOA future traffic needs. It is subject to annual review and possible revision. The LRTP meets the federal long-range transportation planning requirements the MOA needs to apply for federal transportation funding. The Official Streets and Highways Plan (OSHP) identifies (by ordinance) the locations, classifications, and minimum right-of-way requirements of the street and highway system needed to meet LRTP goals over a 25 year planning period. LRTP recommended system improvements are funded through the Statewide Transportation Improvement Program (Federal), Alaska Transportation Fund (Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities [ADOT&PF]), and Capital Improvements Program (MOA). This chapter will describe each mode of transportation as it relates to West Anchorage and how that would have an impact on land use planning. -

Glenn Highway at MP 118 Near Eureka, and the Parks Highway at MP 163 at Little Coal Creek

_____________________________________ ______________________________________ This report is a compilation of traffic data collected, reviewed and analyzed by the Highway Data Section of the Alaska State Department of Transportation & Public Facilities. Preparation & Editing: Edith Yan Cover Photo: Joe Gibbons _____________________________________________________________________________ ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION AND PUBLIC FACILITIES CENTRAL REGION PLANNING HIGHWAY DATA SECTION CENTRAL REGION TRAFFIC VOLUME REPORT 2010-2011-2012 Jennifer W. Witt, Chief of Planning Highway Data Section Howard Helkenn, Highway Data Manager Joe Gibbons, Project Review & Programs Planner Edith Yan, Traffic Data Analyst Tanya Wright, Statistical Technician Stuart Riley, Field Supervisor ______________________________________________________________________________ ANNUAL TRAFFIC VOLUME REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................. Part I Road Listing by Route Name ...................................................... Part II Annual Average Daily Traffic (AADT)/ Daily Vehicle Miles of Travel (DVMT) ..................................... Part III Permanent Traffic Recorder (PTR) Summaries .......................... Part IV Vehicle Classification Data ........................................................ Part V Part I Introduction Introduction The Highway Data Section provides data describing the volumes (number of vehicles) and other characteristics of traffic over the state -

12 Case Studies Prepared for the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities October 2011

Economic and Community Contributions of Selected Alaska Airports: 12 Case Studies Prepared for the Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities October 2011 Wisdom • Trust • Relevance • Innovation Economic and Community Contributions of Selected Alaska Airports: 12 Case Studies Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities October 2011 Prepared by Preparers Team Member Project Role Jonathan King Project Manager Alexus Bond Assistant Project Manager Alejandra Palma Riedel Economist Joel Ainsworth Project Analyst Terri McCoy Technical Editor Please cite as: Northern Economics, Inc. Economic and Community Contributions of Selected Alaska Airports: 12 Case Studies. Prepared for Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities. June 2011. Contents Section Page Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary .............................................................................................................................. ES-1 The Airports and their Communities ............................................................................................. ES-1 Estimates of Total In-State Jobs, Labor, and Economic Output ....................................................... ES-6 Out-of-State Economic Effect ...................................................................................................... ES-10 Return on Annual Maintenance and Operating Costs -

Aviation Forecast Support

FLEET MIX Current Fixed Wing Aircraft at IYS Manufacturer Model FAA Code MTOW Approach Speed Wingspan Tail Height ARC Operator Source Comments Cessna 206 C206 3,600 92 36.00 9.30 B‐I GA FAA Assumed largest GA aircraft Maule M‐7‐260 ‐‐ 2,750 30.83 6.33 A‐I Grasshopper Airliners.net McDonnell Douglas MDC‐DC‐3 ‐‐ 31,300 72 95.00 23.50 A‐III Transnorthern FAA Piper PA‐32‐260 ‐‐ 3,400 32.80 7.90 A‐I Grasshopper wikipedia.org Cherokee Six Grumman HU‐16 Albatross ‐‐ 37,500 96.67 25.83 A‐III GA Multi‐engine amphib Beech E50 Twin Bonanza ‐‐ 7,300 45.25 11.5 ‐I GA wikipedia.org Multi‐engine land Piper PA‐23 Aztec ‐‐ 5,200 37.16 10.33 ‐I GA wikipedia.org Multi‐engine land Republic RC‐3 Seabee ‐‐ 3,150 37.67 10.08 ‐I GA wikipedia.org Single‐engine amphib Piper PA‐32R‐300 ‐‐ 3,600 32.83 9.50 A‐I Penair Airliners.net Saratoga Possible Fixed Wing Aircraft at IYS Manufacturer Model FAA Code MTOW Approach Speed Wingspan Tail Height ARC Operator Source Comments ATR ATR AT72 44,070 105 88.09 25.01 B‐III FedEx FAA Possible use as alternate Cessna 208B ‐‐ 8,750 52.09 14.17 A‐II Hageland Cessna F406 Twin Caravan 9,360 98 49.50 13.16 ‐II Hageland wikipedia.org Guardian, Standard Air Ambulance King Air B200 ‐‐ 12,500 103 54.50 15.00 B‐II LifeMed Airliners.net equipment in Alaska Guardian, Air Ambulance, possible use as Gates Learjet LEARJET 35A/36A LJ28 18,300 143 39.50 12.30 D‐I LifeMed FAA alternate McDonnell Douglas DC‐6 DC6 106,000 108 117.50 28.42 B‐III Everts FAA McDonnell Douglas MDC‐DC‐9‐10/15 90,700 134 89.40 27.60 C‐III Everts FAA Curtis‐Wright C‐46 -

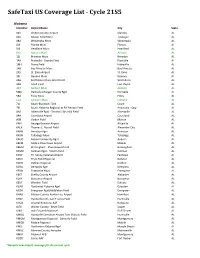

Safetaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5

SafeTaxi US Coverage List - Cycle 21S5 Alabama Identifier Airport Name City State 02A Chilton County Airport Clanton AL 06A Moton Field Muni Tuskegee AL 08A Wetumpka Muni Wetumpka AL 0J4 Florala Muni Florala AL 0J6 Headland Muni Headland AL 0R1 Atmore Muni Atmore AL 12J Brewton Muni Brewton AL 1A9 Prattville - Grouby Field Prattville AL 1M4 Posey Field Haleyville AL 1R8 Bay Minette Muni Bay Minette AL 2R5 St. Elmo Airport St. Elmo AL 33J Geneva Muni Geneva AL 4A6 Scottsboro Muni-Word Field Scottsboro AL 4A9 Isbell Field Fort Payne AL 4R3 Jackson Muni Jackson AL 5M0 Hartselle-Morgan County Rgnl Hartselle AL 5R4 Foley Muni Foley AL 61A Camden Muni Camden AL 71J Ozark-Blackwell Field Ozark AL 79J South Alabama Regional at Bill Benton Field Andalusia - Opp AL 8A0 Albertville Rgnl - Thomas J Brumlik Field Albertville AL 9A4 Courtland Airport Courtland AL A08 Vaiden Field Marion AL KAIV George Downer Airport Aliceville AL KALX Thomas C. Russell Field Alexander City AL KANB Anniston Rgnl Anniston AL KASN Talladega Muni Talladega AL KAUO Auburn University Rgnl Auburn AL KBFM Mobile Downtown Airport Mobile AL KBHM Birmingham - Shuttlesworth Intl Birmingham AL KCMD Cullman Rgnl - Folsom Field Cullman AL KCQF H L Sonny Callahan Airport Fairhope AL KDCU Pryor Field Regional Decatur AL KDHN Dothan Regional Dothan AL KDYA Dempolis Rgnl Dempolis AL KEDN Enterprise Muni Enterprise AL KEET Shelby County Airport Alabaster AL KEKY Bessemer Airport Bessemer AL KEUF Weedon Field Eufaula AL KGAD Northeast Alabama Rgnl Gadsden AL KGZH Evergreen Rgnl/Middleton -

Susitna-Watana Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 14241) Transportation

Susitna-Watana Hydroelectric Project (FERC No. 14241) Transportation Resources Study Study Plan Section 15.7 Initial Study Report Prepared for Alaska Energy Authority Prepared by DOWL-HKM February 2014 Draft INITIAL STUDY REPORT TRANSPORTATION RESOURCES STUDY (15.7) TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................... vi 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................ 1 2. Study Objectives .................................................................................................................... 1 3. Study Area .............................................................................................................................. 2 4. Methods and Variances in 2013 ............................................................................................ 2 4.1. Collect and Review Data ................................................................................................ 2 4.1.1. Variances................................................................................................................. 2 4.2. Inventory Assets and Conduct Any Field Studies ......................................................... 2 4.2.1. Variances................................................................................................................. 2 4.3. Document Existing Conditions ..................................................................................... -

Poker Run Fun...No Snow Though Elections in April a Record 15 Pilots and Their Aircraft Flew in an Annual Thanksgiving Flying During the Jan

Jan.-Feb. 2001- The Official Newsletter of the Ultralight Flyers of Alaska UltraFlight Volume I Number 3 Flying Safely, Just for Fun! BCV-Chugiak, Alaska New Year, New Rules ? Ultralight Flyers of Alaska mem- bers are reminded to renew their memberships, which were due on Jan. 1, 2001. Also if you are flying supervised solo with a two place, check to see if your waiver is still within the 90 day period. If not see Lanse or Mike at Arctic Sparrow Aircraft, Inc. to get a legal waiver. If you are over 40 hours you may take the USUA exam for a UL pilots license, and if you have over 100 hours, you should take the USUA, BFI exam. This notice is in anticipation of new rulings by the FAA on the Sport Pilot Initiative, which may render BFI, and AFI pilots into a FAA Certified Flight Instructor category. Provided you are interested and the National Proposed Rule Making is passed Skis were not used until after the New Year 2001 by Congress in 2001. Poker Run Fun...No Snow Though Elections in April A record 15 pilots and their aircraft flew in an annual Thanksgiving flying During the Jan. 12 meeting it was event in Southcentral Alaska to clear warm skies, but no snow! George determined that an election for all Donart won $350 with the best poker hand at the end of a day of perfect offices were coming due. If you flying. “Man that was great fun, and I won, said George Donart. “I guess are interested in an office or now I can pay my shop bill Mike.” One by our wings and Rotax engines would like to nominate someone lifted us into the clear still air above the muddy ice filled Cook Inlet’s that you know that is a current members please submit the upper Knik Arm, as we departed from Birchwood Airport on the 13th nomination to Arctic Sparrow Air annual ultralight “Poker Run.” Craft, in writing with the name The event sponsored by the Ultralight Flyers of Alaska had a record and position of the intended party. -

No. Location Site Name 1 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Point Wizard

Table J DEC Inventory of Closed Contaminated Sites & Leaking Underground Storage Tank Sites No. Location Site Name 1 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Point Wizard T10517A 2 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Pt Wiz St 10588 3 Adak Adak NSGA New Transportation Building 10590 4 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Point Wizard Station T10592 5 Adak Adak Boy Scout Camp UST BS-1 6 Adak Adak Boy Scout Camp UST BS-2 7 Adak Adak Girl Scout Camp UST GS-1 8 Adak Adak Telephone Substation Building T-100 9 Adak Adak Old Fuel Truck Shop UST T10520A 10 Adak Adak Old Fuel Truck Shop UST T10520B 11 Adak Adak SWMU 56 Public Works Transportation UO UST 12 Adak Adak SA 81 NSGA Gun Turret Hill UST 13 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Point Wizard Station 14 Adak Adak SWMU 12 Quatermasters Road Debris UST26 15 Adak Adak POL Lines UST 09 16 Adak Adak Navy Exchange Bldg 30033 17 Adak Adak SWMU 07 Andrew Bay Drum Disp 2 18 Adak Adak SWMU 27 Lake Leone Drums 19 Adak Adak SWMU 34 Steam Plant 4 Used Oil 20 Adak Adak SWMU 44 AIMD Used Oil Storage 21 Adak Adak SWMU 45 Sewage Treatment Plant 22 Adak Adak SWMU 57 Refueling Dock O/W AST 23 Adak Adak SWMU 64 Tank Farm D 24 Adak Adak SWMU 71 NSGA Fueling Facility 25 Adak Adak SWMU 72 NSGA Transportation Building 10354 26 Adak Adak SWMU 74 Old Batch Facility 27 Adak Adak SA 83 Former Chief's Club Station 28 Adak Adak SA 84 Sand Shed 29 Adak Adak SA 85 New Baler Building 30 Adak Adak SA 89 Tank Farm C 31 Adak Adak SA 75 Asphalt Storage Area 32 Adak Adak SA 91 Airplane Crash Sites 33 Adak Adak SWMU 70 Davis Road Asphalt Drums 34 Adak Adak TFB to TFC Pipeline -

Table J DEC Inventory of Closed Contaminated Sites and Leaking Underground Storage Tank Sites No

Table J DEC Inventory of Closed Contaminated Sites and Leaking Underground Storage Tank Sites No. Location Site Name 1 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Point Wizard T10517A 2 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Pt Wiz St 10588 3 Adak Adak NSGA New Transportation Building 10590 4 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Point Wizard Station T10592 5 Adak Adak Boy Scout Camp UST BS-2 6 Adak Adak Girl Scout Camp UST GS-1 7 Adak Adak Telephone Substation Building T-100 8 Adak Adak Old Fuel Truck Shop UST T10520A 9 Adak Adak Old Fuel Truck Shop UST T10520B 10 Adak Adak SWMU 56 Public Works Transportation UO UST 11 Adak Adak SA 81 NSGA Gun Turret Hill UST 12 Adak Adak SA 87 Old Zeto Point Wizard Station 13 Adak Adak SWMU 12 Quatermasters Road Debris UST26 14 Adak Adak POL Lines UST 09 15 Adak Adak Navy Exchange Bldg 30033 16 Adak Adak SWMU 07 Andrew Bay Drum Disp 2 17 Adak Adak SWMU 27 Lake Leone Drums 18 Adak Adak SWMU 34 Steam Plant 4 Used Oil 19 Adak Adak SWMU 44 AIMD Used Oil Storage 20 Adak Adak SWMU 45 Sewage Treatment Plant 21 Adak Adak SWMU 57 Refueling Dock O/W AST 22 Adak Adak SWMU 64 Tank Farm D 23 Adak Adak SWMU 71 NSGA Fueling Facility 24 Adak Adak SWMU 72 NSGA Transportation Building 10354 25 Adak Adak SWMU 74 Old Batch Facility 26 Adak Adak SA 83 Former Chief's Club Station 27 Adak Adak SA 84 Sand Shed 28 Adak Adak SA 85 New Baler Building 29 Adak Adak SA 89 Tank Farm C 30 Adak Adak SA 75 Asphalt Storage Area 31 Adak Adak SA 91 Airplane Crash Sites 32 Adak Adak SWMU 70 Davis Road Asphalt Drums 33 Adak Adak TFB to TFC Pipeline UST 29 34 Adak Adak TFC to NSGA Pipeline UST 30 35 Adak Adak TFB to Fuel Dock Pipeline UST 31 36 Adak Adak SA 97 Generator Debris UST 33 37 Adak Adak SWMU 01 Andrew Lake OB/OD and Range 38 Adak Adak SWMU 08 Andrew Lake Landfill 39 Adak Adak SA 94 Chemical Weapons Disposal 40 Adak Adak SWMU 03 Clam Lagoon Landfill Table J DEC Inventory of Closed Contaminated Sites and Leaking Underground Storage Tank Sites No.