Beyond Shadows First Nations, Métis and Inuit Student Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Since Time Immemorial, Human Beings Have Used Narrative

Chapter 1 – Introduction Since time immemorial, human beings have used narrative to help us make sense of our experience of life. From the fireside to the theatre, from the television and silver screen to the more recent manifestations of the virtual world, we have used storytelling as a means of providing structure, order, and coherence to what can otherwise appear an overwhelming infinity of random, unrelated events. In ordering the perceived chaos of the world around us into a structure we can grasp, narrative provides insight and understanding not only of events themselves, but on a more fundamental level, of the very essence of what it means to live as a human being. As the primary means by which historical writing is organized, narrative has attracted a large body of historians and philosophers who have grappled with its impact on our understanding of the past. Underlying their work is the tension between historical writing as a reflection of what took place in the past, and the essence of narrative as a creative, imaginative act. The very structure of Aristotelian narrative, with its causal link between events, its clearly defined beginning, middle and end, its promise of catharsis, its theme or moral, reflects an act of imagination on the part of its author. While an effective narrative first and foremost strives to draw us into its world of story and keep us there until the ending, the primary goal of historical writing, in theory at least, is to increase our understanding about the past. While these two goals are not inherently incompatible, they do not always work in concert. -

Languages of the World--Native America

REPOR TRESUMES ED 010 352 46 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD-NATIVE AMERICA FASCICLE ONE. BY- VOEGELIN, C. F. VOEGELIN, FLORENCE N. INDIANA UNIV., BLOOMINGTON REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VI-63-5 PUB DATE JUN64 CONTRACT MC-SAE-9486 EDRS PRICENF-$0.27 HC-C6.20 155P. ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS, 6(6)/1-149, JUNE 1964 DESCRIPTORS- *AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES, *LANGUAGES, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA, ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD THE NATIVE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS OF THE NEW WORLD"ARE DISCUSSED.PROVIDED ARE COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LANGUAGES OF AMERICAN INDIANSNORTH OF MEXICO ANDOF THOSE ABORIGINAL TO LATIN AMERICA..(THIS REPOR4 IS PART OF A SEkIES, ED 010 350 TO ED 010 367.)(JK) $. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION nib Office ofEduc.442n MD WELNicitt weenment Lasbeenreproduced a l l e a l O exactly r o n o odianeting es receivromed f the Sabi donot rfrocestarity it. Pondsof viewor position raimentofficial opinions or pritcy. Offkce ofEducation rithrppologicalLinguistics Volume 6 Number 6 ,Tune 1964 LANGUAGES OF TEM'WORLD: NATIVE AMER/CAFASCICLEN. A Publication of this ARC IVES OF LANGUAGESor 111-E w oRLD Anthropology Doparignont Indiana, University ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS is designed primarily, butnot exclusively, for the immediate publication of data-oriented papers for which attestation is available in the form oftape recordings on deposit in the Archives of Languages of the World. This does not imply that contributors will bere- stricted to scholars working in the Archives at Indiana University; in fact,one motivation for the publication -

2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010

2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010 Description of Table 1. This table shows data for American Indian and Alaska Native tribes alone and alone or in combination for the United States. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native only and one tribe are shown in Column 1. Respondents who reported two or more American Indian or Alaska Native tribes, but no other race, are shown in Column 2. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and at least one other race and one tribe are shown in Column 3. Respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and at least one other race and two or more tribes are shown in Column 4. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native in any combination of race(s) or tribe(s) are shown in Column 5, and is the sum of the numbers in Columns 1 through 4. For a detailed explanation of the alone and alone or in combination concepts used in this table, see the 2010 Census Brief, “The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010” at <www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf>. Table 1. American Indian and Alaska Native Population by Tribe1 for the United States: 2010 Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census, special tabulation. Internet release date: December 2013 Note: Respondents who identified themselves as American Indian or Alaska Native were asked to report their enrolled or principal tribe. Therefore, tribal data in this data product reflect the written tribal entries reported on the questionnaire. -

People of the Dawnland and the Enduring Pursuit of a Native Atlantic World

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MATTHEW R. BAHAR Norman, Oklahoma 2012 “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. Joshua A. Piker, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Catherine E. Kelly ______________________________ Dr. James S. Hart, Jr. ______________________________ Dr. Gary C. Anderson ______________________________ Dr. Karl H. Offen © Copyright by MATTHEW R. BAHAR 2012 All Rights Reserved. For Allison Acknowledgements Crafting this dissertation, like the overall experience of graduate school, occasionally left me adrift at sea. At other times it saw me stuck in the doldrums. Periodically I was tossed around by tempestuous waves. But two beacons always pointed me to quiet harbors where I gained valuable insights, developed new perspectives, and acquired new momentum. My advisor and mentor, Josh Piker, has been incredibly generous with his time, ideas, advice, and encouragement. His constructive critique of my thoughts, methodology, and writing (I never realized I was prone to so many split infinitives and unclear antecedents) was a tremendous help to a graduate student beginning his career. In more ways than he probably knows, he remains for me an exemplar of the professional historian I hope to become. And as a barbecue connoisseur, he is particularly worthy of deference and emulation. -

America, Africa, and Europe Before 1500

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Module 1 America, Africa, and Europe before 1500 Essential Question Why might a U.S. historian study the Americas, Africa, and Europe before 1500? About the Photo: American buffalo were In this module you will learn the histories of three regions—the a vital food source for many Native Americas, West Africa, and Europe—whose people would come together American groups. and forever change North America. What You Will Learn … Lesson 1: The Earliest Americans.. 6 Explore ONLINE! The Big Idea Native American societies developed across North and VIDEOS, including... South America. • Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations Lesson 2: Native American Cultures .. 11 The Big Idea Many diverse Native American cultures developed • Corn across the different geographic regions of North America. • Machu Picchu Lesson 3: Trading Kingdoms of West Africa . 19 • Salt The Big Idea Using trade to gain wealth, Ghana, Mali, and Songhai • Origins of Western Culture were West Africa’s most powerful kingdoms. • Rome Falls Lesson 4: Europe before 1500.. 23 • The First Crusade The Big Idea New ideas and trade changed Europeans’ lives. Document-Based Investigations Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Interactive Map: Migrations of Early People Image with Hotspots: The Chinook Image Carousel: Empires of Gold and Salt 2 Module 1 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events Beginnings–AD 1500 Explore ONLINE! Module Events World 38,000 BC c. 38,000–10,000 BC Paleo-Indians migrate to the Americas. c. 5000 BC Communities in Mexico 5000 BC cultivate corn. -

Historical Methods in James P. Howley's the Beothucks

A Few Fabulous Fragments: Historical Methods in James P. Howley’s The Beothucks JEFF A. WEBB* Since it was published in 1915, James Howley’s The Beothucks has been an essential source for historians and novelists alike. Howley’s training as a geologist and surveyor shaped his scholarship. Rather than seeing his book as a history of the Beothuk, he saw it as preserving the memory of the Indigenous people of the island of Newfoundland. He deferred to philologists and ethnographers on issues of theory and most effectively marshalled his critical sense when evaluating the oral testimony he collected. This reading of the book revisits the foundational text and shows the lasting legacy of Howley’s scientific method and cultural assumptions upon the historiography and popular culture of the Beothuk. Depuis sa publication en 1915, The Beothuks de James Howley s’est révélé une source essentielle tant pour les historiens que pour les romanciers. La formation de Howley comme géologue et arpenteur transparaît dans son travail de recherche. Plutôt que de voir son livre comme une histoire des Béothuks, l’auteur l’a perçu comme un ouvrage préservant la mémoire des Autochtones de l’île de Terre-Neuve. Il s’en est remis aux philologues et aux ethnographes à propos des questions de théorie et a fait appel à son sens critique au moment d’évaluer les témoignages oraux recueillis par lui. La présente lecture de l’ouvrage permet de réexaminer ce texte fondateur et de présenter le legs durable de la méthode scientifique de Howley et de ses hypothèses culturelles sur l’historiographie et la culture populaire au sujet des Béothuks. -

2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File 2020 Census of Population and Housing

2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File 2020 Census of Population and Housing Technical Documentation Issued February 2021 SFNRD/20-02 Additional For additional information concerning the Census Redistricting Data Information Program and the Public Law 94-171 Redistricting Data, contact the Census Redistricting and Voting Rights Data Office, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 20233 or phone 1-301-763-4039. For additional information concerning data disc software issues, contact the COTS Integration Branch, Applications Development and Services Division, Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 20233 or phone 1-301-763-8004. For additional information concerning data downloads, contact the Dissemination Outreach Branch of the Census Bureau at <[email protected]> or the Call Center at 1-800-823-8282. 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File Issued February 2021 2020 Census of Population and Housing SFNRD/20-01 U.S. Department of Commerce Wynn Coggins, Acting Agency Head U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Dr. Ron Jarmin, Acting Director Suggested Citation FILE: 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File Prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION: 2020 Census National Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Technical Documentation Prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Dr. Ron Jarmin, Acting Director Dr. Ron Jarmin, Deputy Director and Chief Operating Officer Albert E. Fontenot, Jr., Associate Director for Decennial Census Programs Deborah M. Stempowski, Assistant Director for Decennial Census Programs Operations and Schedule Management Michael T. Thieme, Assistant Director for Decennial Census Programs Systems and Contracts Jennifer W. Reichert, Chief, Decennial Census Management Division Chapter 1. -

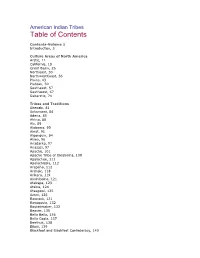

Table of Contents

American Indian Tribes Table of Contents Contents-Volume 1 Introduction, 3 Culture Areas of North America Arctic, 11 California, 19 Great Basin, 26 Northeast, 30 NorthwestCoast, 36 Plains, 43 Plateau, 50 Southeast, 57 Southwest, 67 Subarctic, 74 Tribes and Traditions Abenaki, 81 Achumawi, 84 Adena, 85 Ahtna, 88 Ais, 89 Alabama, 90 Aleut, 91 Algonquin, 94 Alsea, 96 Anadarko, 97 Anasazi, 97 Apache, 101 Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, 108 Apalachee, 111 Apalachicola, 112 Arapaho, 112 Archaic, 118 Arikara, 119 Assiniboine, 121 Atakapa, 123 Atsina, 124 Atsugewi, 125 Aztec, 126 Bannock, 131 Bayogoula, 132 Basketmaker, 132 Beaver, 135 Bella Bella, 136 Bella Coola, 137 Beothuk, 138 Biloxi, 139 Blackfoot and Blackfeet Confederacy, 140 Caddo tribal group, 146 Cahuilla, 153 Calusa, 155 CapeFear, 156 Carib, 156 Carrier, 158 Catawba, 159 Cayuga, 160 Cayuse, 161 Chasta Costa, 163 Chehalis, 164 Chemakum, 165 Cheraw, 165 Cherokee, 166 Cheyenne, 175 Chiaha, 180 Chichimec, 181 Chickasaw, 182 Chilcotin, 185 Chinook, 186 Chipewyan, 187 Chitimacha, 188 Choctaw, 190 Chumash, 193 Clallam, 194 Clatskanie, 195 Clovis, 195 CoastYuki, 196 Cocopa, 197 Coeurd'Alene, 198 Columbia, 200 Colville, 201 Comanche, 201 Comox, 206 Coos, 206 Copalis, 208 Costanoan, 208 Coushatta, 209 Cowichan, 210 Cowlitz, 211 Cree, 212 Creek, 216 Crow, 222 Cupeño, 230 Desert culture, 230 Diegueño, 231 Dogrib, 233 Dorset, 234 Duwamish, 235 Erie, 236 Esselen, 236 Fernandeño, 238 Flathead, 239 Folsom, 242 Fox, 243 Fremont, 251 Gabrielino, 252 Gitksan, 253 Gosiute, 254 Guale, 255 Haisla, 256 Han, 256 -

NA Boyer Ch 01.V2

CHAPTER 1 Native Peoples of America, to 1500 iawatha was in the depths of despair. For years his people, a group of five HNative American nations known as the Iroquois, had engaged in a seem- ingly endless cycle of violence and revenge. Iroquois families, villages, and nations fought one another, and neighboring Indians attacked relentlessly. When Hiawatha tried to restore peace within his own Onondaga nation, an evil sorcerer caused the deaths of his seven beloved daughters. Grief- stricken, Hiawatha wandered alone into the forest. After several days, he experienced a series of visions. First he saw a flock of wild ducks fly up from the lake, taking the water with them. Hiawatha walked onto the dry lakebed, gathering the beautiful purple-and-white shells that lay there. He saw the shells, called wampum, as symbolic “words” of condolence that, when prop- erly strung into belts and ceremonially presented, would soothe anyone’s grief, no matter how deep. Then he met a holy man named Deganawidah (the Peacemaker), who presented him with several wampum belts and spoke the appropriate words—one to dry his weeping eyes, another to open his ears to words of peace and reason, and a third to clear his throat so that he himself could once again speak peacefully and reasonably. Deganawidah CHAPTER OUTLINE and Hiawatha took the wampum to the five Iroquois nations. To each they introduced the ritual of condolence as a new message of peace. The Iroquois The First Americans, c. 13,000–2500 B.C. subsequently submerged their differences and created a council of chiefs Cultural Diversity, ca. -

500 Years of Indigenous Resistance Gord Hill

500 YEARS OF INDIGENOUS RESISTANCE GORD HILL 500 years of Indigenous Resistance © Gord Hill 2009 Tis edition © PM Press 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover and interior design by Daniel Meltzer 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2009901389 ISBN 978-1-60486-106-8 Published by: PM Press PO Box 23912 Oakland, CA 94623 www.pmpress.org Printed in the USA on recycled paper. Table of Contents 4 Foreword 6 Introduction 7 Te Pre-Columbian World 11 Te Genocide Begins 15 Expansion, Exploitation, and Extermination 18 Te Penetration of North America 24 Te European Struggle for Hegemony 27 Tragedy: Te United States is Created 30 Revolutions in the “New World” 35 Manifest Destiny and the U.S. Indian Wars 37 Afrikan Slavery, Afrikan Rebellion, and the U.S. Civil War 40 Black Reconstruction and Deconstruction 43 Te Colonization of Canada 50 Extermination and Assimilation: Two Methods, One Goal 58 Te People AIM for Freedom 63 Te Struggle for Land 66 In Total Resistance FOREWoRD Sixteen years afer it was originally published in the frst issue of the revo- lutionary Indigenous newspaper OH-TOH-KIN, 500 Years of Indigenous Resistance remains an important and relevent history of the colonization of the Americas and the resistance to it. It begins with the arrival of Co- lumbus and fnishes with the resistance struggles that defned the early nineties; the Lubicons, the Mohawks, and the Campaign For 500 Years Of Resistance that occurred all over the Americas, and was a historical precurser to the well-known Zapatista uprising of 1994. -

Pre-Confederation

Canadian History: Pre-Confederation John Belshaw Canadian History: Pre-Confederation Canadian History: Pre-Confederation John Douglas Belshaw Unless otherwise noted within this book, this book is released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License also known as a CC-BY license. This means you are free to copy, redistribute, modify or adapt this book. Under this license, anyone who redistributes or modifies this textbook, in whole or in part, can do so for free providing they properly attribute the book as follows: Canadian History: Pre-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license. Additionally, if you redistribute this textbook, in whole or in part, in either a print or digital format, then you must retain on every physical and/or electronic page the following attribution: Download this book for free at http://open.bccampus.ca For questions regarding this license or to learn more about the BC Open Textbook Project, please contact [email protected]. Cover image: Nanaimo Indians, Vancouver Island, British Columbia by US National Archives bot is in the public domain. Canadian History: Pre-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Contents Dedication x About the Book xi Acknowledgments xii Author's Notes xiii Preface xv Chapter 1. When Was Canada? 1.1 Introduction 2 cc-by-nc-sa 1.2 The Writing of History 3 cc-by-nc-sa 1.3 Making Histories 10 cc-by-nc-sa 1.4 The Current State of Historical Writing in Canada 20 cc-by-nc-sa 1.5 Summary 25 cc-by-nc-sa Chapter 2. -

PART I: NAME SEQUENCE Name Sequence

Name Sequence PART I: NAME SEQUENCE A-ch‘ang Abor USE Achang Assigned collective code [sit] Aba (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) USE Chiriguano UF Adi Abaknon Miri Assigned collective code [phi] Miśing (Philippine (Other)) Aborlan Tagbanwa UF Capul USE Tagbanua Inabaknon Abua Kapul Assigned collective code [nic] Sama Abaknon (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) Abau Abujhmaria Assigned collective code [paa] Assigned collective code [dra] (Papuan (Other)) (Dravidian (Other)) UF Green River Abulas Abaw Assigned collective code [paa] USE Abo (Cameroon) (Papuan (Other)) Abazin UF Ambulas Assigned collective code [cau] Maprik (Caucasian (Other)) Acadian (Louisiana) Abenaki USE Cajun French Assigned collective code [alg] Acateco (Algonquian (Other)) USE Akatek UF Abnaki Achangua Abia Assigned collective code [sai] USE Aneme Wake (South American (Other)) Abidji Achang Assigned collective code [nic] Assigned collective code [sit] (Niger-Kordofanian (Other)) (Sino-Tibetan (Other)) UF Adidji UF A-ch‘ang Ari (Côte d'Ivoire) Atsang Abigar Ache USE Nuer USE Guayaki Abkhaz [abk] Achi Abnaki Assigned collective code [myn] USE Abenaki (Mayan languages) Abo (Cameroon) UF Cubulco Achi Assigned collective code [bnt] Rabinal Achi (Bantu (Other)) Achinese [ace] UF Abaw UF Atjeh Bo Cameroon Acholi Bon (Cameroon) USE Acoli Abo (Sudan) Achuale USE Toposa USE Achuar MARC Code List for Languages October 2007 page 11 Name Sequence Achuar Afar [aar] Assigned collective code [sai] UF Adaiel (South American Indian Danakil (Other)) Afenmai UF Achuale USE Etsako Achuara Jivaro Afghan