Historical Methods in James P. Howley's the Beothucks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895 An Economic History Reader Collected, Transcribed and Annotated by Christopher Willmore Victoria, British Columbia April 2020 Table of Contents WAYS OF LIFE AND WORK .................................................................................................................. 4 Fog and Foundering (1754) ............................................................................................................................ 4 Hostile Waters (1761) .................................................................................................................................... 4 Imports of Salt (1819) .................................................................................................................................... 5 The Great Fire of St. John’s (1846) ................................................................................................................. 5 Visiting Newfoundland’s Fisheries in 1849 (1849) .......................................................................................... 9 The Newfoundland Seal Hunt (1871) ........................................................................................................... 15 The Inuit Seal Hunt (1889) ........................................................................................................................... 19 The Truck, or Credit, System (1871) ............................................................................................................. 20 The Preparation of -

Introduction Since Time Immemorial, Human Beings Have Used Narrative

Chapter 1 – Introduction Since time immemorial, human beings have used narrative to help us make sense of our experience of life. From the fireside to the theatre, from the television and silver screen to the more recent manifestations of the virtual world, we have used storytelling as a means of providing structure, order, and coherence to what can otherwise appear an overwhelming infinity of random, unrelated events. In ordering the perceived chaos of the world around us into a structure we can grasp, narrative provides insight and understanding not only of events themselves, but on a more fundamental level, of the very essence of what it means to live as a human being. As the primary means by which historical writing is organized, narrative has attracted a large body of historians and philosophers who have grappled with its impact on our understanding of the past. Underlying their work is the tension between historical writing as a reflection of what took place in the past, and the essence of narrative as a creative, imaginative act. The very structure of Aristotelian narrative, with its causal link between events, its clearly defined beginning, middle and end, its promise of catharsis, its theme or moral, reflects an act of imagination on the part of its author. While an effective narrative first and foremost strives to draw us into its world of story and keep us there until the ending, the primary goal of historical writing, in theory at least, is to increase our understanding about the past. While these two goals are not inherently incompatible, they do not always work in concert. -

A Beothuk Skeleton

Edinburgh Research Explorer A Beothuk skeleton (not) in a glass case Citation for published version: Harries, J 2016, A Beothuk skeleton (not) in a glass case: rumours of bones and the remembrance of an exterminated people in Newfoundland - the emotive immateriality of human remains. in J-M Dreyfus & É Anstett (eds), Human remains in society: Curation and exhibition in the aftermath of genocide and mass- violence., 9, Human Remains and Violence, Manchester Univ. Press, Manchester. <http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526107381/> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Human remains in society General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 A Beothuk Skeleton (not) in a Glass Case: Rumours of Bones and the Remembrance of an Exterminated People in Newfoundland John Harries, Social Anthropology, The University of Edinburgh The emotive immateriality of human remains This chapter is about the human remains and how human remains inhabit the public sphere after their exhumation. -

GFW Community Profile Design Draft

Project Co‐ordinator: Gary Hennessey, Economic Development Officer Town of Grand Falls‐Windsor, NL Phone: 709‐489‐0483 / Fax: 709‐489‐0465 Email: [email protected] www.grandfallswindsor.com Project Facilitator: Kris Stone Research, Design & Layout By: Kris Stone Photos By: Kris Stone The Town of Grand Falls‐Windsor Grand Falls‐Windsor Heritage Society Up Sky Down Films Elmo Hewle MAYOR’S MESSAGE Welcome to the Grand Falls‐Windsor WCommunity Profile. This document has been created to showcase informaon on the many remarkable aspects that our community has to offer to current and potenal residents, as well as business owners. There are secons on demographics, aracons, events, tourism, community organizaons, the various types of businesses and industry in the area, as well as a lile bit of history on how our town got its start and became the municipality it is today. Grand Falls‐Windsor is the largest town in Central Newfoundland. The community is located along the banks of the Exploits River, seled within a serene valley atmosphere—a great place to live, work, and play. Its locaon also makes it a favourable place for doing business, as it is easily accessible from virtually all areas of the island. For this reason, Grand Falls‐Windsor has become known as a major service centre for Central Newfoundland and a hub for most of the island. Over the years our town connues to grow and prosper, with numerous housing developments steadily building family friendly neighbourhoods. There are many new and exisng businesses thriving and diversifying our economy in areas such as Aquaculture, Mining, Healthcare, Informaon Technology and Health Science Research, Post‐secondary Educaon, and Retail. -

Languages of the World--Native America

REPOR TRESUMES ED 010 352 46 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD-NATIVE AMERICA FASCICLE ONE. BY- VOEGELIN, C. F. VOEGELIN, FLORENCE N. INDIANA UNIV., BLOOMINGTON REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VI-63-5 PUB DATE JUN64 CONTRACT MC-SAE-9486 EDRS PRICENF-$0.27 HC-C6.20 155P. ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS, 6(6)/1-149, JUNE 1964 DESCRIPTORS- *AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES, *LANGUAGES, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA, ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD THE NATIVE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS OF THE NEW WORLD"ARE DISCUSSED.PROVIDED ARE COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LANGUAGES OF AMERICAN INDIANSNORTH OF MEXICO ANDOF THOSE ABORIGINAL TO LATIN AMERICA..(THIS REPOR4 IS PART OF A SEkIES, ED 010 350 TO ED 010 367.)(JK) $. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION nib Office ofEduc.442n MD WELNicitt weenment Lasbeenreproduced a l l e a l O exactly r o n o odianeting es receivromed f the Sabi donot rfrocestarity it. Pondsof viewor position raimentofficial opinions or pritcy. Offkce ofEducation rithrppologicalLinguistics Volume 6 Number 6 ,Tune 1964 LANGUAGES OF TEM'WORLD: NATIVE AMER/CAFASCICLEN. A Publication of this ARC IVES OF LANGUAGESor 111-E w oRLD Anthropology Doparignont Indiana, University ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS is designed primarily, butnot exclusively, for the immediate publication of data-oriented papers for which attestation is available in the form oftape recordings on deposit in the Archives of Languages of the World. This does not imply that contributors will bere- stricted to scholars working in the Archives at Indiana University; in fact,one motivation for the publication -

2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010

2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010 Description of Table 1. This table shows data for American Indian and Alaska Native tribes alone and alone or in combination for the United States. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native only and one tribe are shown in Column 1. Respondents who reported two or more American Indian or Alaska Native tribes, but no other race, are shown in Column 2. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and at least one other race and one tribe are shown in Column 3. Respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and at least one other race and two or more tribes are shown in Column 4. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native in any combination of race(s) or tribe(s) are shown in Column 5, and is the sum of the numbers in Columns 1 through 4. For a detailed explanation of the alone and alone or in combination concepts used in this table, see the 2010 Census Brief, “The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010” at <www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf>. Table 1. American Indian and Alaska Native Population by Tribe1 for the United States: 2010 Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census, special tabulation. Internet release date: December 2013 Note: Respondents who identified themselves as American Indian or Alaska Native were asked to report their enrolled or principal tribe. Therefore, tribal data in this data product reflect the written tribal entries reported on the questionnaire. -

People of the Dawnland and the Enduring Pursuit of a Native Atlantic World

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MATTHEW R. BAHAR Norman, Oklahoma 2012 “THE SEA OF TROUBLE WE ARE SWIMMING IN”: PEOPLE OF THE DAWNLAND AND THE ENDURING PURSUIT OF A NATIVE ATLANTIC WORLD A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. Joshua A. Piker, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Catherine E. Kelly ______________________________ Dr. James S. Hart, Jr. ______________________________ Dr. Gary C. Anderson ______________________________ Dr. Karl H. Offen © Copyright by MATTHEW R. BAHAR 2012 All Rights Reserved. For Allison Acknowledgements Crafting this dissertation, like the overall experience of graduate school, occasionally left me adrift at sea. At other times it saw me stuck in the doldrums. Periodically I was tossed around by tempestuous waves. But two beacons always pointed me to quiet harbors where I gained valuable insights, developed new perspectives, and acquired new momentum. My advisor and mentor, Josh Piker, has been incredibly generous with his time, ideas, advice, and encouragement. His constructive critique of my thoughts, methodology, and writing (I never realized I was prone to so many split infinitives and unclear antecedents) was a tremendous help to a graduate student beginning his career. In more ways than he probably knows, he remains for me an exemplar of the professional historian I hope to become. And as a barbecue connoisseur, he is particularly worthy of deference and emulation. -

America, Africa, and Europe Before 1500

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Module 1 America, Africa, and Europe before 1500 Essential Question Why might a U.S. historian study the Americas, Africa, and Europe before 1500? About the Photo: American buffalo were In this module you will learn the histories of three regions—the a vital food source for many Native Americas, West Africa, and Europe—whose people would come together American groups. and forever change North America. What You Will Learn … Lesson 1: The Earliest Americans.. 6 Explore ONLINE! The Big Idea Native American societies developed across North and VIDEOS, including... South America. • Mexico’s Ancient Civilizations Lesson 2: Native American Cultures .. 11 The Big Idea Many diverse Native American cultures developed • Corn across the different geographic regions of North America. • Machu Picchu Lesson 3: Trading Kingdoms of West Africa . 19 • Salt The Big Idea Using trade to gain wealth, Ghana, Mali, and Songhai • Origins of Western Culture were West Africa’s most powerful kingdoms. • Rome Falls Lesson 4: Europe before 1500.. 23 • The First Crusade The Big Idea New ideas and trade changed Europeans’ lives. Document-Based Investigations Graphic Organizers Interactive Games Interactive Map: Migrations of Early People Image with Hotspots: The Chinook Image Carousel: Empires of Gold and Salt 2 Module 1 DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-A Timeline of Events Beginnings–AD 1500 Explore ONLINE! Module Events World 38,000 BC c. 38,000–10,000 BC Paleo-Indians migrate to the Americas. c. 5000 BC Communities in Mexico 5000 BC cultivate corn. -

RESEARCH NOTE Beothuks and Methodists

RESEARCH NOTE Beothuks and Methodists THE EXTINCT BEOTHUK INDIANS of Newfoundland continue to intrigue and puzzle anthropologists and historians.1 Most discussions have included wonder ment that this population kept itself almost entirely aloof for several centuries from the European fishermen and settlers on the island, and maintained its defiant attitude to the end in the early 19th century. There seem to have been no peaceful exchanges of goods or friendly relations after the contacts in the early 17th and perhaps the 16th centuries. The evidence for whites living with the Beothuks, willingly or not, is dubious. There are no known cases of intermar riage or even of sexual relations between whites and Beothuks, and thus no métis or individuals of mixed race who might have functioned as go-betweens. Even the rare cases of adoption of orphaned Beothuk children led to no friendly inter course as far as we know. The reasons for this avoidance pattern by the Beothuks, as well as for their refusal to adopt firearms and European cod-fish ing technology or to engage in the fur trade, remain subjects of speculation. Whatever the explanations, the Beothuks chose to maintain their geographical and social distance from the Europeans. Their "strategy of withdrawal"2 was aberrant in terms of the usual pattern of contact and acculturation among New World aboriginal groups. It has been pointed out that there was no missionary influence, English or French, on the Beothuks, and that this is a unique situation in the Northeast. This has led a number of authors writing about the fate of the Beothuks to spec ulate on what might have happened had missionaries been able to reach them and convert them to Christianity.3 The examples of the Moravians in Labrador and the Jesuits in New France have been offered as illustrations of such success. -

2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File 2020 Census of Population and Housing

2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File 2020 Census of Population and Housing Technical Documentation Issued February 2021 SFNRD/20-02 Additional For additional information concerning the Census Redistricting Data Information Program and the Public Law 94-171 Redistricting Data, contact the Census Redistricting and Voting Rights Data Office, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 20233 or phone 1-301-763-4039. For additional information concerning data disc software issues, contact the COTS Integration Branch, Applications Development and Services Division, Census Bureau, Washington, DC, 20233 or phone 1-301-763-8004. For additional information concerning data downloads, contact the Dissemination Outreach Branch of the Census Bureau at <[email protected]> or the Call Center at 1-800-823-8282. 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File Issued February 2021 2020 Census of Population and Housing SFNRD/20-01 U.S. Department of Commerce Wynn Coggins, Acting Agency Head U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Dr. Ron Jarmin, Acting Director Suggested Citation FILE: 2020 Census National Redistricting Data Summary File Prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION: 2020 Census National Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Technical Documentation Prepared by the U.S. Census Bureau, 2021 U.S. CENSUS BUREAU Dr. Ron Jarmin, Acting Director Dr. Ron Jarmin, Deputy Director and Chief Operating Officer Albert E. Fontenot, Jr., Associate Director for Decennial Census Programs Deborah M. Stempowski, Assistant Director for Decennial Census Programs Operations and Schedule Management Michael T. Thieme, Assistant Director for Decennial Census Programs Systems and Contracts Jennifer W. Reichert, Chief, Decennial Census Management Division Chapter 1. -

Table of Contents

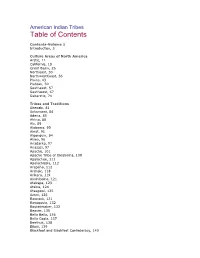

American Indian Tribes Table of Contents Contents-Volume 1 Introduction, 3 Culture Areas of North America Arctic, 11 California, 19 Great Basin, 26 Northeast, 30 NorthwestCoast, 36 Plains, 43 Plateau, 50 Southeast, 57 Southwest, 67 Subarctic, 74 Tribes and Traditions Abenaki, 81 Achumawi, 84 Adena, 85 Ahtna, 88 Ais, 89 Alabama, 90 Aleut, 91 Algonquin, 94 Alsea, 96 Anadarko, 97 Anasazi, 97 Apache, 101 Apache Tribe of Oklahoma, 108 Apalachee, 111 Apalachicola, 112 Arapaho, 112 Archaic, 118 Arikara, 119 Assiniboine, 121 Atakapa, 123 Atsina, 124 Atsugewi, 125 Aztec, 126 Bannock, 131 Bayogoula, 132 Basketmaker, 132 Beaver, 135 Bella Bella, 136 Bella Coola, 137 Beothuk, 138 Biloxi, 139 Blackfoot and Blackfeet Confederacy, 140 Caddo tribal group, 146 Cahuilla, 153 Calusa, 155 CapeFear, 156 Carib, 156 Carrier, 158 Catawba, 159 Cayuga, 160 Cayuse, 161 Chasta Costa, 163 Chehalis, 164 Chemakum, 165 Cheraw, 165 Cherokee, 166 Cheyenne, 175 Chiaha, 180 Chichimec, 181 Chickasaw, 182 Chilcotin, 185 Chinook, 186 Chipewyan, 187 Chitimacha, 188 Choctaw, 190 Chumash, 193 Clallam, 194 Clatskanie, 195 Clovis, 195 CoastYuki, 196 Cocopa, 197 Coeurd'Alene, 198 Columbia, 200 Colville, 201 Comanche, 201 Comox, 206 Coos, 206 Copalis, 208 Costanoan, 208 Coushatta, 209 Cowichan, 210 Cowlitz, 211 Cree, 212 Creek, 216 Crow, 222 Cupeño, 230 Desert culture, 230 Diegueño, 231 Dogrib, 233 Dorset, 234 Duwamish, 235 Erie, 236 Esselen, 236 Fernandeño, 238 Flathead, 239 Folsom, 242 Fox, 243 Fremont, 251 Gabrielino, 252 Gitksan, 253 Gosiute, 254 Guale, 255 Haisla, 256 Han, 256 -

NA Boyer Ch 01.V2

CHAPTER 1 Native Peoples of America, to 1500 iawatha was in the depths of despair. For years his people, a group of five HNative American nations known as the Iroquois, had engaged in a seem- ingly endless cycle of violence and revenge. Iroquois families, villages, and nations fought one another, and neighboring Indians attacked relentlessly. When Hiawatha tried to restore peace within his own Onondaga nation, an evil sorcerer caused the deaths of his seven beloved daughters. Grief- stricken, Hiawatha wandered alone into the forest. After several days, he experienced a series of visions. First he saw a flock of wild ducks fly up from the lake, taking the water with them. Hiawatha walked onto the dry lakebed, gathering the beautiful purple-and-white shells that lay there. He saw the shells, called wampum, as symbolic “words” of condolence that, when prop- erly strung into belts and ceremonially presented, would soothe anyone’s grief, no matter how deep. Then he met a holy man named Deganawidah (the Peacemaker), who presented him with several wampum belts and spoke the appropriate words—one to dry his weeping eyes, another to open his ears to words of peace and reason, and a third to clear his throat so that he himself could once again speak peacefully and reasonably. Deganawidah CHAPTER OUTLINE and Hiawatha took the wampum to the five Iroquois nations. To each they introduced the ritual of condolence as a new message of peace. The Iroquois The First Americans, c. 13,000–2500 B.C. subsequently submerged their differences and created a council of chiefs Cultural Diversity, ca.