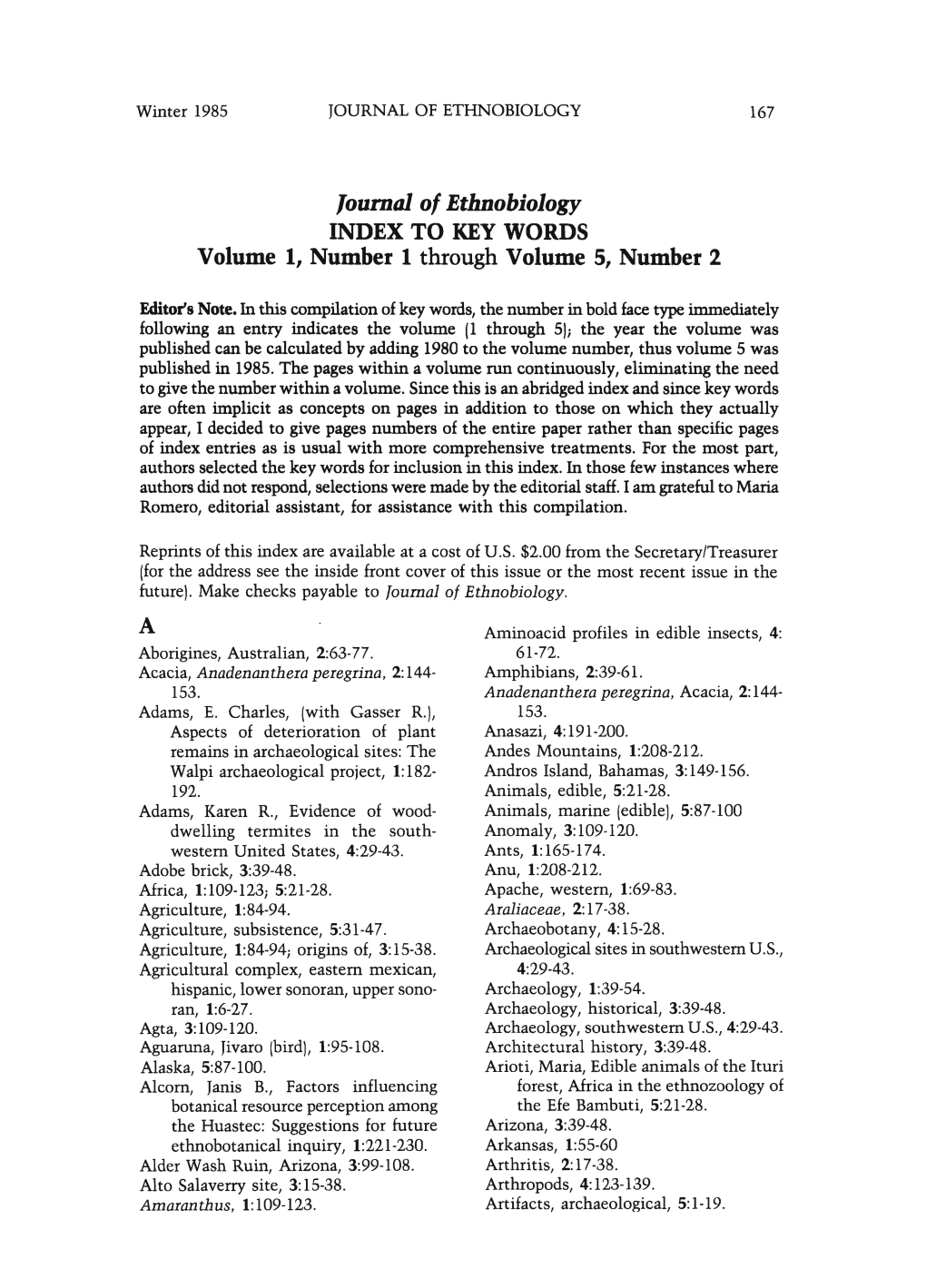

Ioumal of Ethnobiology INDEX to KEY WORDS Volume I, Number 1 Through Volume 5, Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maya Knowledge and "Science Wars"

Journal of Ethnobiology 20(2); 129-158 Winter 2000 MAYA KNOWLEDGE AND "SCIENCE WARS" E. N. ANDERSON Department ofAnthropology University ofCalifornia, Riverside Riverside, CA 92521~0418 ABSTRACT.-Knowledge is socially constructed, yet humans succeed in knowing a great deal about their environments. Recent debates over the nature of "science" involve extreme positions, from claims that allscience is arbitrary to claims that science is somehow a privileged body of truth. Something may be learned by considering the biological knowledge of a very different culture with a long record of high civilization. Yucatec Maya cthnobiology agrees with contemporary international biological science in many respects, almost all of them highly specific, pragmatic and observational. It differs in many other respects, most of them highly inferential and cosmological. One may tentatively conclude that common observation of everyday matters is more directly affected by interaction with the nonhuman environment than is abstract deductive reasoning. but that social factors operate at all levels. Key words: Yucatec Maya, ethnoornithology, science wars, philosophy ofscience, Yucatan Peninsula RESUMEN.-EI EI conocimiento es una construcci6n social, pero los humanos pueden aprender mucho ce sus alrededores. Discursos recientes sobre "ciencia" incluyen posiciones extremos; algunos proponen que "ciencia" es arbitrario, otros proponen que "ciencia" es verdad absoluto. Seria posible conocer mucho si investiguemos el conocimiento biol6gico de una cultura, muy difcrente, con una historia larga de alta civilizaci6n. EI conodrniento etnobiol6gico de los Yucatecos conformc, mas 0 menos, con la sciencia contemporanea internacional, especial mente en detallas dcrivadas de la experiencia pragmatica. Pero, el es deferente en otros respectos-Ios que derivan de cosmovisi6n 0 de inferencia logical. -

The Amazonian Travels of Richard Evans Schultes Introduction: Early Life and Explorations

The Amazonian Travels of Richard Evans Schultes Introduction: Early Life and Explorations By Brian Hettler and Mark Plotkin April 8, 2019 The following text is from the interactive map available at the link: banrepcultural.org/schultes Introduction Richard Evans Schultes – ethnobotanist, taxonomist, writer and photographer – is regarded as one of the most important plant explorers of the 20th century. In December 1941, Schultes entered the Amazon rainforest on a mission to study how indigenous peoples used plants for medicinal, ritual and practical purposes. He went on to spend over a decade immersed in near-continuous fieldwork, becoming one of the most important plant explorers of the 20th century. Schultes’ area of focus was the northwest Amazon, an area that had remained largely unknown to the outside world, isolated by the Andes to the west and dense jungles and impassable rapids on all other sides. In this remote area, Schultes lived amongst little studied tribes, mapped uncharted rivers, and was the first scientist to explore some areas that have not been researched since. His notes and photographs are some of the only existing documentation of indigenous cultures in a region of the Amazon on the cusp of change. In this interactive map journal, retrace Schultes’ extraordinary adventures and experience the thrill of scientific exploration and discovery. Through a series of interactive maps, explore the magical landscapes and indigenous cultures of the Amazon Rainforest, presented through the lens of Schultes’ vivid photography and ethnobotanical research. 1 Early Life in Boston Richard Evans Schultes was born in Boston, Massachusetts on January 12, 1915. -

ISE Newsletter, Volume 1 Issue 2, Without Photos

Volume 1, Issue 2 June 2009 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: ISE’S 1ST ASIAN 2 THE ISE’S FIRST ASIAN CONFERENCE OF ETHNOBIOLOGY CONFERENCE TAIWAN, 21-29 OCTOBER 2009 Profile: Dr. Yih-Ren 3 During the 11th International In order to demonstrate the Resource Management Profile: RECAP 4 Congress of Ethnobiology in unique and diverse cultural 3. Natural Disaster Zones UPDATES ON ISE 4 Peru, the idea of an Asian characteristics of the area, and and Environmental ACTIVITIES regional conference was therefore the topic of “Sacred Mastery posited. When Dr. Yih-Ren Places”, which bears great 4. Local Indigenous Scientific Re-Evisioning Activity 4 Lin, Director of the Research local representation, was Education Global Coalition and 5 Centre for Austronesian chosen as an entrance point Ethics Committee Peoples at Providence into this conference. In order 5. Indigenous Policies and University, was elected as the to reflect the commitment to Biological/Cultural Ethics Toolkit 6 Asian Representative for ISE, research ethics and explore Diversity Conservation 2009-2011 Darrell 7 he was encouraged to hold the academic and practical 6. Traditional Ecological Posey Fellowship the First Asian Conference of dialectical spirit in this Recipients Knowledge Ethnobiology (FACE; www.ise- interdisciplinary field, the topic 7. Indigenous Area Reports: 2006-2008 8 asia.org). of participatory research Research and Research Darrell Posey Small The aim of this conference is methodology was specifically Methodology added. CONFERENCE 10 to address topics that have 8. Religion and Indigenous been long-term priorities for The focus of the ISE FACE is REPORTS Sacred Spaces the ISE that also relate to the “The Position of Indigenous Snowchange 10 portrayal of Indigenous culture Peoples, Sacred Places and 9. -

Thinking About the Human Bias in Our Ecological Analyses for Biodiversity Conservation Sérgio De Faria Lopes1,*

REVIEW Ethnobiology and Conservation 2017, 6:14 (18 August 2017) doi:10.15451/ec2017086.14124 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com The other side of Ecology: thinking about the human bias in our ecological analyses for biodiversity conservation Sérgio de Faria Lopes1,* ABSTRACT Ecology as a science emerged within a classic Cartesian positivist context, in which relationships should be understood by the division of knowledge and its subsequent generalization. Overtime, ecology has addressed many questions, from the processes that lead to the origin and maintenance of life to modern theories of trophic webs and non equilibrium. However, the ecological models and ecosystem theories used in the field of ecology have had difficulty integrating man into analysis, although humans have emerged as a global force that is transforming the entirety of planet. In this sense, currently, advances in the field of the ecology that develop outside of research centers is under the spotlight for social, political, economic and environmental goals, mainly due the environmental crisis resulting from overexploitation of natural resources and habitat fragmentation. Herein a brief historical review of ecology as science and humankind’s relationship with nature is presented, with the objective of assessing the impartiality and neutrality of scientific research and new possibilities of understanding and consolidating knowledge, specifically local ecological knowledge. Moreover, and in a contemporary way, the human being presence in environmental relationships, both as a study object, as well as an observer, proposer of interpretation routes and discussion, requires new possibilities. Among these proposals, the human bias in studies of the biodiversity conservation emerges as the other side of ecology, integrating scientific knowledge with local ecological knowledge and converging with the idea of complexity in the relationships of humans with the environment. -

Vol. II ETHNOPHARMACOLOGIC SEARCH for PSYCHOACTIVE

ETHNOPHARMACOLOGIC SEARCH for PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS • 2017 50th Anniversary Symposium › June 6 – 8, 2017 ESPD50.com Vol. II Table of Contents Foreword by Sir Ghillean Prance 1 Scientific Director of the Eden Project, Director (Ret.), Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew [Introduction] What a Long, Strange Trip it’s Been: Reflections on the Ethnopharmacologic Search for Psychoactive Drugs (1967-2017) 2 Dennis McKenna [From the Archive] A Scientist Looks at the Hippies 10 Stephen Szára AYAHUASCA & THE AMAZON 23 Ayahuasca: A Powerful Epistemological Wildcard in a Complex, Fascinating and Dangerous World 24 Luis Eduardo Luna From Beer to Tobacco: A Probable Prehistory of Ayahuasca and Yagé 36 Constantino Manuel Torres Plant Use and Shamanic Dietas in Contemporary Ayahuasca Shamanism in Peru 55 Evgenia Fotiou Spirit Bodies, Plant Teachers and Messenger Molecules in Amazonian Shamanism 70 Glenn H. Shepard Broad Spectrum Roles of Harmine in Ayahuasca 82 Dale Millard Viva Schultes - A Retrospective [Keynote] 95 Mark J. Plotkin, Brian Hettler & Wade Davis AFRICA, AUSTRALIA & SOUTHEAST ASIA 121 Kabbo’s !Kwaiń: The Past, Present and Possible Future of Kanna 122 Nigel Gericke Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) as a Potential Therapy for Opioid Dependence 151 Christopher R. McCurdy The Ibogaine Project: Urban Ethnomedicine for Opioid Use Disorder 160 Kenneth Alper Psychoactive Initiation Plant Medicines: Their Role in the Healing and Learning Process of South African and Upper Amazonian Traditional Healers 175 Jean-Francois Sobiecki Psychoactive Australian Acacia Species and Their Alkaloids 181 Snu Voogelbreinder From ‘There’ to ‘Here’: Psychedelic Natural Products and Their Contributions to Medicinal Chemistry [Keynote] 202 David E. Nichols MEXICO & CENTRAL AMERICA 219 Fertile Grounds? – Peyote and the Human Reproductive System 220 Stacy B. -

Introduction Since Time Immemorial, Human Beings Have Used Narrative

Chapter 1 – Introduction Since time immemorial, human beings have used narrative to help us make sense of our experience of life. From the fireside to the theatre, from the television and silver screen to the more recent manifestations of the virtual world, we have used storytelling as a means of providing structure, order, and coherence to what can otherwise appear an overwhelming infinity of random, unrelated events. In ordering the perceived chaos of the world around us into a structure we can grasp, narrative provides insight and understanding not only of events themselves, but on a more fundamental level, of the very essence of what it means to live as a human being. As the primary means by which historical writing is organized, narrative has attracted a large body of historians and philosophers who have grappled with its impact on our understanding of the past. Underlying their work is the tension between historical writing as a reflection of what took place in the past, and the essence of narrative as a creative, imaginative act. The very structure of Aristotelian narrative, with its causal link between events, its clearly defined beginning, middle and end, its promise of catharsis, its theme or moral, reflects an act of imagination on the part of its author. While an effective narrative first and foremost strives to draw us into its world of story and keep us there until the ending, the primary goal of historical writing, in theory at least, is to increase our understanding about the past. While these two goals are not inherently incompatible, they do not always work in concert. -

Anthropology 213 Ethnobotany: Plants & Peoples

ANTHROPOLOGY 213 ETHNOBOTANY: PLANTS & PEOPLES BULLETIN INFORMATION ANTH 213 – Ethnobotany: Plants and Peoples (3 credit hours) Course Description: Anthropological overview of the interactions between cultures around the world and the plants that affect them, from cultural, biological, archaeological, and linguistic points of view. SAMPLE COURSE OVERVIEW Every culture depends on plants for needs as diverse as food, shelter, clothing, and medicines. Certain plants hold symbolic meanings for people. Plants affect people in many ways. Ethnobotany—the interrelationships between cultures and plants—is a field of study by disciplines as diverse as anthropology, botany, chemistry, pharmacognosy, and engineering. This course provides students with a multi-cultural overview of human-plant interactions through the lenses of the four anthropological subfields of cultural anthropology, biological anthropology, linguistics, and archaeology. No background in either anthropology or botany is needed, just a curiosity to learn more about human-plant relationships. The emphasis is on cultural anthropology: students participate in a class research project on an ethnobotanical subject. ITEMIZED LEARNING OUTCOMES Upon successful completion of ANTH 213, students will be able to: 1. Define ethnobotany; 2. List the subfields of anthropology and summarize how each intersects with ethnobotany; 3. Outline differences in worldviews and how those affect human-nature relationships; 4. Summarize important ethnobotanical issues; 5. Give examples of ethical responsibilities in human subject research; 6. Be professionally and nationally CITI certified for human subject research; 7. Conduct an oral interview; 8. Apply the scientific method by stating a testable hypothesis, researching the topic, compiling data, and evaluating the findings. SAMPLE REQUIRED TEXTS/SUGGESTED READINGS/MATERIALS No textbook. -

Richard Schultes Seemed the Epitome of the Plant Explorer of the Victorian Era

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES RICHARD EVANS SCHULTES 1915–2001 A Biographical Memoir by LUIS SEQUEIRA Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoirs, COPYRIGHT 2006 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. RICHARD EVANS SCHULTES January 12, 1915–April 10, 2001 BY LUIS SEQUEIRA HE SPEAKER JUST DID not look the part. He was tall, thin, T clean-shaven with closely cropped hair, and wore a tweed coat and a Harvard tie. He spoke softly, with a clipped Boston accent, and peered at the students behind wire- rimmed glasses while he explained in a bemused tone the advantages of the use of snuff as a means to clear a stuffy nose. A highly conservative, proper Bostonian no doubt and about to deliver what we expected would be a scholarly, probably dull lecture on the taxonomy of some plant fam- ily. Yet, as he spoke, all the students in a course on eco- nomic botany at Harvard in the spring of 1949 became gradually transfixed when he began to describe some of his experiences while exploring the upper reaches of the Ama- zon River in Colombia. He seemed the most unlikely per- son to have survived alone for several years in one of the most remote areas of the world, where he faced incredibly harrowing, perilous conditions. He had gone to the jungle in Colombia to trace the origin of curare in 1941, but remained there for the next eight years to collect wild specimens of the Hevea rubber tree as part of a mission for the U.S. -

A Molecular Taxonomic Treatment of the Neotropical Genera

An Intrageneric and Intraspecific Study of Morphological and Genetic Variation in the Neotropical Compsoneura and Virola (Myristicaceae) by Royce Allan David Steeves A Thesis Presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Botany Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Royce Steeves, August, 2011 ABSTRACT AN INTRAGENERIC AND INTRASPECIFIC STUDY OF MORPHOLOGICAL AND GENETIC VARIATION IN THE NEOTROPICAL COMPSONEURA AND VIROLA (MYRISTICACEAE) Royce Allan David Steeves Advisor: University of Guelph, 2011 Dr. Steven G. Newmaster The Myristicaceae, or nutmeg family, consists of 21 genera and about 500 species of dioecious canopy to sub canopy trees that are distributed worldwide in tropical rainforests. The Myristicaceae are of considerable ecological and ethnobotanical significance as they are important food for many animals and are harvested by humans for timber, spices, dart/arrow poison, medicine, and a hallucinogenic snuff employed in medico-religious ceremonies. Despite the importance of the Myristicaceae throughout the wet tropics, our taxonomic knowledge of these trees is primarily based on the last revision of the five neotropical genera completed in 1937. The objective of this thesis was to perform a molecular and morphological study of the neotropical genera Compsoneura and Virola. To this end, I generated phylogenetic hypotheses, surveyed morphological and genetic diversity of focal species, and tested the ability of DNA barcodes to distinguish species of wild nutmegs. Morphological and molecular analyses of Compsoneura. indicate a deep divergence between two monophyletic clades corresponding to informal sections Hadrocarpa and Compsoneura. Although 23 loci were tested for DNA variability, only the trnH-psbA intergenic spacer contained enough variation to delimit 11 of 13 species sequenced. -

Languages of the World--Native America

REPOR TRESUMES ED 010 352 46 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD-NATIVE AMERICA FASCICLE ONE. BY- VOEGELIN, C. F. VOEGELIN, FLORENCE N. INDIANA UNIV., BLOOMINGTON REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VI-63-5 PUB DATE JUN64 CONTRACT MC-SAE-9486 EDRS PRICENF-$0.27 HC-C6.20 155P. ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS, 6(6)/1-149, JUNE 1964 DESCRIPTORS- *AMERICAN INDIAN LANGUAGES, *LANGUAGES, BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA, ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD THE NATIVE LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS OF THE NEW WORLD"ARE DISCUSSED.PROVIDED ARE COMPREHENSIVE LISTINGS AND DESCRIPTIONS OF THE LANGUAGES OF AMERICAN INDIANSNORTH OF MEXICO ANDOF THOSE ABORIGINAL TO LATIN AMERICA..(THIS REPOR4 IS PART OF A SEkIES, ED 010 350 TO ED 010 367.)(JK) $. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH,EDUCATION nib Office ofEduc.442n MD WELNicitt weenment Lasbeenreproduced a l l e a l O exactly r o n o odianeting es receivromed f the Sabi donot rfrocestarity it. Pondsof viewor position raimentofficial opinions or pritcy. Offkce ofEducation rithrppologicalLinguistics Volume 6 Number 6 ,Tune 1964 LANGUAGES OF TEM'WORLD: NATIVE AMER/CAFASCICLEN. A Publication of this ARC IVES OF LANGUAGESor 111-E w oRLD Anthropology Doparignont Indiana, University ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS is designed primarily, butnot exclusively, for the immediate publication of data-oriented papers for which attestation is available in the form oftape recordings on deposit in the Archives of Languages of the World. This does not imply that contributors will bere- stricted to scholars working in the Archives at Indiana University; in fact,one motivation for the publication -

2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010

2010 Census CPH-T-6. American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes in the United States and Puerto Rico: 2010 Description of Table 1. This table shows data for American Indian and Alaska Native tribes alone and alone or in combination for the United States. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native only and one tribe are shown in Column 1. Respondents who reported two or more American Indian or Alaska Native tribes, but no other race, are shown in Column 2. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and at least one other race and one tribe are shown in Column 3. Respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native and at least one other race and two or more tribes are shown in Column 4. Those respondents who reported as American Indian or Alaska Native in any combination of race(s) or tribe(s) are shown in Column 5, and is the sum of the numbers in Columns 1 through 4. For a detailed explanation of the alone and alone or in combination concepts used in this table, see the 2010 Census Brief, “The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010” at <www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf>. Table 1. American Indian and Alaska Native Population by Tribe1 for the United States: 2010 Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2010 Census, special tabulation. Internet release date: December 2013 Note: Respondents who identified themselves as American Indian or Alaska Native were asked to report their enrolled or principal tribe. Therefore, tribal data in this data product reflect the written tribal entries reported on the questionnaire. -

Program of the 34Th Annual Meeting of the Society of Ethnobiology

Program of the 34th Annual Meeting of the Society of Ethnobiology Historical and Archaeological Perspecives in Ethnobiology May 4 - 7, 2011 Columbus, Ohio Welcome to the 34th Annual Meeting of the Society of Ethnobiology This meeting continues a long tradition in our Society. Since the first Society meeting in 1978 – when many of the world’s leading ethnobiologists came together to share ideas – the Society has been at the forefront of inter-disciplinary ethnobiological research. Equally important, since those first days, the Society has created and nurtured a worldwide ethnobiological community that has become the intellec- tual and emotional home for scholars world-wide. Our meetings are the forum for bringing this community together and our world-class journal is the venue for sharing our research more broadly. For my part, my deep commitment to the Society began as a student in 1984, at the 7th Annual meetings. At that time, I was fortunate to present the results of my Masters research (while referring to text on glossy erasable typing paper!) in Harriet Kuhnlein’s session on her inter-disciplinary and community-based “Nuxalk Food and Nutrition Project”. This project and indeed my opportunity to be involved in it (as a Masters student in Archaeology, of all things), exemplifies the potential of ethnobiology to make linkages. Looking at the society today, we see abundant linkages between academic disciplines, between academic and non-academic knowledge holders, and between advanced scholars and new researchers. This is what the Society of Ethnobiology is all about. In the past four years, your Board and many other Society volunteers have worked hard to promote the Society’s goals by focus- ing on these linkages.