Maya Knowledge and "Science Wars"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

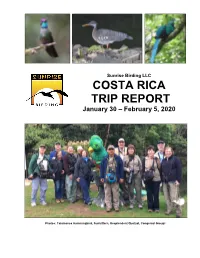

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Tapera Dromococcyx

HOST LIST OF AVIAN BROOD PARASITES - 3 - CUCULIFORMES; Neomorphidae Peter E. Lowther, Field Museum version 14 Sep 2011 Tapera Tapera Thunberg 1819, Handlingar Kungl Vetenskaps och vitterheetssamhället i Göteborg, 3, p. 1. American Striped Cuckoo, Tapera naevia (Linnaeus) 1766 Systema Naturae, ed. 12, p. 170. Distribution. – Neotropics. General life history information found in Friedmann 1933, Belcher and Smooker 1936, Sick 1953, Haverschmidt 1955, 1961, Wetmore 1968, Morton and Farabaugh 1979, Salvador 1982, Payne 2005, Pulgarín-R. et al. 2007 (see also additional references in host list below). Host list. – From Friedmann 1933; see also Davis 1940, Loetscher 1952, Sick 1953, 1993, Haverschmidt 1955, 1961, 1968, Wetmore 1968 1, Salvador 1982, Kiff and Williams 1978, Payne 2005. Brief mention of this cuckoo in studies of actual or potential hosts given by: Skutch 1969, Thomas 1983, Freed 1987 2 TYRANNIDAE White-headed Marsh-Tyrant, Arundinicola leucocephala tody-flycatcher, Todirostrum spp. * (Sick 1953, 1993 lists species as “apparently also” a host) flycatcher, Myiozetetes spp. * (Sick 1953, 1993 lists species as “apparently also” a host) FURNARIIDAE Chotoy Spinetail, Schoeniophylax phryganophila Sooty-fronted Spinetail, Synallaxis frontalis Azara's Spinetail, Synallaxis azarae 3 (includes superciliosa) Pale-breasted Spinetail, Synallaxis albescens Spix’s Spinetail, Synallaxis spixi Plain-crowned Spinetail, Synallaxis gujanensis Rufous-breasted Spinetail, Synallaxis erythrothorax Stripe-breasted Spinetail, Synallaxis cinnamomea Yellow-chinned Spinetail, Certhiaxis cinnamomeus Short-billed Castanero, Asthenes [pyrrholeuca] baeri Plain Thornbird, Phacellodomus [rufifrons] rufifrons Greater Thornbird, Phacellodomus ruber Red-eyed Thornbird, Phacellodomus erythrophthalmus Buff-fronted Foliage-Gleaner, Philydor rufus TROGLODYTIDAE Rufous-and-white Wren, Thryothorus rufalbus Plain W ren, Thryothorus modestus EMBERIZIDAE Black-striped Sparrow, Arremonops conirostris Dromococcyx Dromococcyx W ied-Neuwied 1832, Beitrage zur Naturgeschichte von Brasil. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Cuckoos Supports a Polyphyletic Origin of Brood Parasitism

Molecular phylogeny of cuckoos supports a polyphyletic origin of brood parasitism S. ARAGO N,*A.P.MéLLER,*J.J.SOLER & M. SOLER *Laboratoire d'Ecologie, CNRS-URA 258, Universite Pierre et Marie Curie, BaÃt. A, 7e eÂtage, 7, quai St. Bernard, Case 237, F-75252 Paris Cedex 05, France Departamento de BiologõÂa Animal y EcologõÂa, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Granada, E-18071 Granada, Spain Keywords: Abstract brood parasitism; We constructed a molecular phylogeny of 15 species of cuckoos using cuculiformes; mitochondrial DNA sequences spanning 553 nucleotide bases of the cyto- cytochrome b; chrome b gene and 298 nucleotide bases of the ND2 gene. A parallel analysis DNA sequencing; for the cytochrome b gene including published sequences in the Genbank ND2. database was performed. Phylogenetic analyses of the sequences were done using parsimony, a sequence distance method (Fitch-Margoliash), and a character-state method which uses probabilities (maximum likelihood). Phenograms support the monophyly of three major clades: Cuculinae, Phaenicophaeinae and Neomorphinae-Crotophaginae. Clamator, a strictly parasitic genus traditionally included within the Cuculinae, groups together with Coccyzus (a nonobligate parasite) and some nesting cuckoos. Tapera and Dromococcyx, the parasitic cuckoos from the New World, appear as sister genera, close to New World cuckoos: Neomorphinae and Crotophaginae. Based on the results, and being conscious that a more strict resolution of the relationships among the three major clades is required, we postulate that brood parasitism has a polyphyletic origin in the Cuculiformes, with parasite species being found within the three de®ned clades. Evidence suggests that species within each clade share a common parasitic ancestor, but some show partial or total loss of brood parasitic behaviour. -

ISE Newsletter, Volume 1 Issue 2, Without Photos

Volume 1, Issue 2 June 2009 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: ISE’S 1ST ASIAN 2 THE ISE’S FIRST ASIAN CONFERENCE OF ETHNOBIOLOGY CONFERENCE TAIWAN, 21-29 OCTOBER 2009 Profile: Dr. Yih-Ren 3 During the 11th International In order to demonstrate the Resource Management Profile: RECAP 4 Congress of Ethnobiology in unique and diverse cultural 3. Natural Disaster Zones UPDATES ON ISE 4 Peru, the idea of an Asian characteristics of the area, and and Environmental ACTIVITIES regional conference was therefore the topic of “Sacred Mastery posited. When Dr. Yih-Ren Places”, which bears great 4. Local Indigenous Scientific Re-Evisioning Activity 4 Lin, Director of the Research local representation, was Education Global Coalition and 5 Centre for Austronesian chosen as an entrance point Ethics Committee Peoples at Providence into this conference. In order 5. Indigenous Policies and University, was elected as the to reflect the commitment to Biological/Cultural Ethics Toolkit 6 Asian Representative for ISE, research ethics and explore Diversity Conservation 2009-2011 Darrell 7 he was encouraged to hold the academic and practical 6. Traditional Ecological Posey Fellowship the First Asian Conference of dialectical spirit in this Recipients Knowledge Ethnobiology (FACE; www.ise- interdisciplinary field, the topic 7. Indigenous Area Reports: 2006-2008 8 asia.org). of participatory research Research and Research Darrell Posey Small The aim of this conference is methodology was specifically Methodology added. CONFERENCE 10 to address topics that have 8. Religion and Indigenous been long-term priorities for The focus of the ISE FACE is REPORTS Sacred Spaces the ISE that also relate to the “The Position of Indigenous Snowchange 10 portrayal of Indigenous culture Peoples, Sacred Places and 9. -

Thinking About the Human Bias in Our Ecological Analyses for Biodiversity Conservation Sérgio De Faria Lopes1,*

REVIEW Ethnobiology and Conservation 2017, 6:14 (18 August 2017) doi:10.15451/ec2017086.14124 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com The other side of Ecology: thinking about the human bias in our ecological analyses for biodiversity conservation Sérgio de Faria Lopes1,* ABSTRACT Ecology as a science emerged within a classic Cartesian positivist context, in which relationships should be understood by the division of knowledge and its subsequent generalization. Overtime, ecology has addressed many questions, from the processes that lead to the origin and maintenance of life to modern theories of trophic webs and non equilibrium. However, the ecological models and ecosystem theories used in the field of ecology have had difficulty integrating man into analysis, although humans have emerged as a global force that is transforming the entirety of planet. In this sense, currently, advances in the field of the ecology that develop outside of research centers is under the spotlight for social, political, economic and environmental goals, mainly due the environmental crisis resulting from overexploitation of natural resources and habitat fragmentation. Herein a brief historical review of ecology as science and humankind’s relationship with nature is presented, with the objective of assessing the impartiality and neutrality of scientific research and new possibilities of understanding and consolidating knowledge, specifically local ecological knowledge. Moreover, and in a contemporary way, the human being presence in environmental relationships, both as a study object, as well as an observer, proposer of interpretation routes and discussion, requires new possibilities. Among these proposals, the human bias in studies of the biodiversity conservation emerges as the other side of ecology, integrating scientific knowledge with local ecological knowledge and converging with the idea of complexity in the relationships of humans with the environment. -

Roadrunner Fact Sheet

Roadrunner Fact Sheet Common Name: Roadrunner Scientific Name: Geococcyx Californianus & Geococcyx Velox Wild Status: Not Threatened Habitat: Arid dessert and shrub Country: United States, Mexico, and Central America Shelter: These birds nest 1-3 meters off the ground in low trees, shrubs, or cactus Life Span: 8 years Size: 2 feet in length; 8-15 ounces Details The genus Geococcyx consists of two species of bird: the greater roadrunner and the lesser roadrunner. They live in the arid climates of Southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central America. Though these birds can fly, they spend most of their time running from shrub to shrub. Roadrunners spend the entirety of their day hunting prey and dodging predators. It's a tough life out there in the wild! These birds eat insects, small reptiles and mammals, arachnids, snails, other birds, eggs, fruit, and seeds. One thing that these birds do not have to worry about is drinking water. They intake enough moisture through their diet and are able to secrete any excess salt build-up through glands in their eyes. This adaptation is common in sea birds as their main source of hydration is the ocean. The fact that roadrunners have adapted this trait as well goes to show how well they are suited for their environment. A roadrunner will mate for life and will travel in pairs, guarding their territory from other roadrunners. When taking care of the nest, both male and female take turns incubating eggs and caring for their young. The young will leave the nest after a couple weeks and will then learn foraging techniques for a few days until they are left to fend for themselves. -

2019 Belize and Tikal Tour 1

Belize and Tikal Guides: Ernesto Carman, Eagle-Eye Tours February 4 - 13, 2019 Jared Clarke BIRD SPECIES Seen/ Common Name Scientific Name Heard TINAMIFORMES: Tinamidae 1 Great Tinamou Tinamus major H 2 Slaty-breasted Tinamou Crypturellus boucardi H 3 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui H ANSERIFORMES: Anatidae 4 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis 1 5 Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor 1 6 Blue-winged Teal Spatula discors 1 7 Ring-necked Duck Aythya collaris 1 8 Lesser Scaup Aythya affinis 1 GALLIFORMES: Odontophoridae 9 Black-throated Bobwhite Colinus nigrogularis 1 GALLIFORMES: Cracidae 10 Plain Chachalaca Ortalis vetula 1 11 Crested Guan Penelope purpurascens 1 12 Great Curassow Crax rubra 1 GALLIFORMES: Phasianidae 13 Ocellated Turkey Meleagris ocellata 1 PODICIPEDIFORMES: Podicipedidae 14 Least Grebe Tachybaptus dominicus 1 15 Pied-billed Grebe Podilymbus podiceps 1 CICONIIFORMES: Ciconiidae 16 Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 1 17 Wood Stork Mycteria americana 1 SULIFORMES: Fregatidae 18 Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens 1 SULIFORMES: Phalacrocoracidae 19 NeotroPic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus 1 SULIFORMES: Anhingidae 20 Anhinga Anhinga anhinga 1 PELECANIFORMES: Pelecanidae 21 American White Pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos 1 22 Brown Pelican Pelecanus occidentalis 1 PELECANIFORMES: Ardeidae 23 Reddish Egret Egretta rufescens 1 24 Least Bittern Ixobrychus exilis 1 25 Bare-throated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma mexicanum 1 Page 1 of 11 Belize and Tikal Guides: Ernesto Carman, Eagle-Eye Tours February 4 - 13, -

THE EUPHONIA Quarterly Journal of Mexican Avifauna Volume 1, Number 2 December 1992 the EUPHONIA Quarterly Journal of Mexican Avifauna

THE EUPHONIA Quarterly Journal of Mexican Avifauna Volume 1, Number 2 December 1992 THE EUPHONIA Quarterly Journal of Mexican Avifauna Editor: Kurt Radamaker Associate Editors: Michael A. Patten, Deb Davidson Spanish Consultant: Luis Santaella Consultant: Steve N.G. Howell Proofreaders: Richard A. Erickson, Bob Pann Circulation Manager: Cindy Ludden For an annual subscription to The Euphonia, please send 15.00 dollars U.S. payable to The Euphonia P.O. Box 8045, Santa Maria, California, 93456-8045, U.S.A. Checks drawn on Bancomer in Pesos accepted. The Euphonia encourages you to send in manuscripts. Appropriate topics range from recent sightings to scientific studies of Mexican birds. Feature articles in Spanish are encouraged. Please send manuscripts, preferably on diskette written in Wordperfect (although almost any major word processor file will suffice), to Kurt Radamaker, P.O. Box 8045, Santa Maria, California 93456, U.S.A. Please send summaries for Recent Ornithological Literature to Michael A. Patten at P.O. Box 8561, Riverside, California, 92515-8561, U.S.A. Recent sightings (with details) should be sent to Luis Santaella, 919 Second St., Encinitas, California 92024, U.S.A. Contents 27 OBSERVATIONS OF NORTH AMERICAN MIGRANT BIRDS IN THE REVILLAGIGEDO ISLANDS Steve N.G. Howell and Sophie Webb 34 PARASITISM OF YELLOW-OLIVE FLY CATCHER BY THE PHEASANT CUCKOO Richard G. Wilson 37 SEMIPALMATED SANDPIPER RECORDS FOR BAJA CALIFORNIA Thomas E. Wurster and Kurt Radamaker 39 RECENT RECORDS OF MAROON-CHESTED GROUND-DOVE IN MEXICO Steve N.G. Howell 42 OBSERVATION OF A BENDIRE'S THRASHER FROM NORTHEAST BAJA CALIFORNIA Brian Daniels, Doug Willick and Thomas E. -

Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan 2016

PARTNERS IN FLIGHT LANDBIRD CONSERVATION PLAN 2016 Revision for Canada and Continental United States FOREWORD: A NEW CALL TO ACTION PROJECT LEADS Kenneth V. Rosenberg, Cornell Lab of Ornithology Judith A. Kennedy, Environment and Climate Change Canada The Partners in Flight (PIF) 2016 Landbird Conservation Plan Revision comes Randy Dettmers, United States Fish and Wildlife Service at an important time in conserving our heritage of an abundant and diverse Robert P. Ford, United States Fish and Wildlife Service avifauna. There is now an urgent need to bridge the gap between bird Debra Reynolds, United States Fish and Wildlife Service conservation planning and implementation. AUTHORS John D. Alexander, Klamath Bird Observatory Birds and their habitats face unprecedented threats from climate change, Carol J. Beardmore, Sonoran Joint Venture; United States Fish and Wildlife Service poorly planned urban growth, unsustainable agriculture and forestry, and Peter J. Blancher, Environment and Climate Change Canada (emeritus) a widespread decline in habitat quantity and quality. The spectacle of bird Roxanne E. Bogart, United States Fish and Wildlife Service migration is being diminished by direct mortality as every year millions Gregory S. Butcher, United States Forest Service of birds die from anthropogenic sources. As documented in this Plan, Alaine F. Camfield, Environment and Climate Change Canada nearly 20% of U.S. and Canadian landbird species are on a path towards Andrew Couturier, Bird Studies Canada endangerment and extinction in the absence of conservation action. Dean W. Demarest, United States Fish and Wildlife Service Randy Dettmers, United States Fish and Wildlife Service We know, however, that when we use the best science to develop Wendy E. -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Effectiveness and Utility of Acoustic Recordings for Surveying Tropical Birds Antonio Celis-Murillo University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Faculty Research & Creative Activity Biological Sciences January 2012 Effectiveness and utility of acoustic recordings for surveying tropical birds Antonio Celis-Murillo University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Jill L. Deppe Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Michael P. Ward University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Celis-Murillo, Antonio; Deppe, Jill L.; and Ward, Michael P., "Effectiveness and utility of acoustic recordings for surveying tropical birds" (2012). Faculty Research & Creative Activity. 153. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research & Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Field Ornithology J. Field Ornithol. 83(2):166–179, 2012 DOI: 10.1111/j.1557-9263.2012.00366.x Effectiveness and utility of acoustic recordings for surveying tropical birds Antonio Celis-Murillo1,2,3,5 Jill L. Deppe4 and Michael P. Ward2,3 1School of Integrative Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, Illinois 61821, USA 2Illinois Natural History Survey, Champaign, Illinois 61821, USA 3Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, Illinois 61821, USA 4Eastern Illinois University, Department of Biological Sciences, Charleston, Illinois 61920, USA Received 21 September 2011; accepted 20 February 2012 ABSTRACT. Although acoustic recordings have recently gained popularity as an alternative to point counts for surveying birds, little is known about the relative performance of the two methods for detecting tropical bird species across multiple vegetation types.