VU Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uitvoeringsprogramma Aanpak Binnenstad Onderscheidt 6 Prioriteiten Die Samen En in Wisselwerking Met Elkaar Bijdragen Aan De Opgaven in De Binnenstad

AANPAK BINNENSTAD Uitvoeringsprogramma december 2020 i. Inhoud 1. Vooraf 3 Van ambitie naar maatregelen 4 2. Aanleiding 5 3. Ambitie 6 4. Uitvoeringsprogramma 7 5. Opgaven 9 BINNENSTAD AANPAK Enkele voorbeelden van Aanpak Binnenstad 10 2 6. Maatregelen 11 6.1 Functiemenging en diversiteit 12 6.2 Beheer en handhaving 16 6.3 Een waardevolle bezoekerseconomie 20 6.4 Versterken van de culturele verscheidenheid en buurtidentiteiten 23 6.5 Bevorderen van meer en divers woningaanbod 26 6.6 Meer verblijfsruimte en groen in de openbare ruimte 29 7. Organisatie en financiën 32 8. Samenwerking en voortgang 33 UITVOERINGSPROGRAMMA 1. Vooraf In mei 2020 is in een raadsbrief de Aanpak Binnenstad gelanceerd. Deze aanpak combineert maatregelen en visie voor zowel de korte als langere termijn, formuleert de opgaven in de binnenstad breed en in samenhang, maar stelt tegelijkertijd ook prioriteiten. Deze aanpak bouwt voort op dat wat is ingezet door de gemeente en tal van anderen rond de binnenstad, maar maakt waar nodig ook scherpe keuzes. En deze aanpak pakt problemen aan én biedt perspectief. Wat ons treft in de vele gesprekken die Een deel van deze maatregelen is reeds De kracht van een set maatregelen is dat wij in de afgelopen maanden gevoerd in gang gezet, want we beginnen niet bij ze goed te adresseren en concreet zijn. hebben met bewoners, ondernemers, nul. Andere maatregelen nemen wij in De kwetsbaarheid is dat ze een zekere vastgoedeigenaren en culturele onderzoek of voorbereiding en met weer mate van uitwisselbaarheid suggereren. instellingen, is dat er een breed gedragen andere starten wij in het kader van dit Dat laatste willen wij weerleggen. -

A B N N N Z Z Z C D E F G H I J K

A8 COENTUNNELWEG W WEG ZIJKANAAL G AMMERGOU G R O 0 T E Gemeente Zaanstad D N M E E R Gemeente Oostzaan K L E I N E AA V A N B BOZEN M E E R NOORDER BOS LANDSMEER E EKSTRAA SYMON SPIERSWEG V E E R MEERTJE T ZUIDEINDE AFRIKAHAVEN NOORDER-IJPLAS NOOR : BAARTHAVEN D ZEE ISAAC KAN Broekermeerpolder NOORDERWEG AAL ( IN AANLEG ) K N O O P P U N T ZUIDEINDE DORS MACHINEWEG RUIGOORD ZAANDAM C O E N P L E I N WIM ARKEN AE THOMASSENHAVEN HET SCHOUW Volgermeer- Gemeente Waterland SPORTPARK R M EER EN W E G BR OEKE Belmermeerpolder RINGWEG-NOO MIDD Hemspoortunnel OOSTZANER- polder Houtrak- WERF DIRK KADOELENWEG polder R D Gemeente Landsmeer RIJPERWEG METSELAARHAVEN A 1 0 SWEG AMERIKAHAVEN R OOSTZANERWERF H e m p o n t ENAA STELLINGWEG MOL S T R A A T SPORTPARK STEN T OR MELKWEG UITDAM O O TW B EG ANKERWEG W E G RUIJGOORDWEG WESTHAVENWEG STOOM KADOELEN BROEKERGOUW TER A M D M Burkmeer- ER STELLINGWEG UIT D IE ELBAWEG C A R L R E AVEN SLOCH Veenderij H Windturbine IJNI HORNWEG ERSH polder V o e t v e e r CACAO AVEN KADO SPORTPARK Grote Blauwe Polder KOMETENSINGEL Sportpark Zunderdorp E R R.I. Groote OT DIE LANDS ELENWEG TUINDORP KADOELEN LATEXWEG IJpolder METEORENWEG Tuindorp AAL SL NOORDERBREEDTE N WESTHAVEN OOSTZAAN KA COENTUNNEL CORNELIS DOUWESWEG Oostzaan MIDDENWEG MEERDER JAN VAN RIEBEECK G O U W HOLY KOFFIEWEG RUIGOORD MIDDENWEG RUIGOORD PETROLEUM HOLLANDSCH HOLYSLOOT DIJK NDAMMER HAVEN NOORD E : INCX POPP AUSTRALIEHA V E N ZIJKANAAL I POMONASTRAAT NWEG HORNWEG WESTERLENGTE RWEG OCEANE USSEL A N A N A S HAVEN NIEUWE HEMWEG P L E I N BUIKSLOOT RDE R.I. -

DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM Een Geologische Stadswandeling

EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans OVER DE AUTEUR Dr. Wim de Gans (Amersfoort, 1941) studeerde aardwetenschappen aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na zijn afstuderen was hij als docent achtereenvolgens verbonden aan de Rijks Universiteit Groningen en de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na deze universitaire loopbaan was hij jaren lang werkzaam als districtsgeoloog bij de Rijks Geologische Dienst (RGD), die in 1997 is overgegaan naar TNO. De schrijver is bij TNO voor de Geologische Dienst Nederland vooral bezig met het populariseren van de geologie van Nederland. Hij schreef talrijke publicaties en enkele boeken waaronder het Geologieboek Nederland (ANWB/TNO). DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans VOORWOORD Wanneer je door de binnenstad van Amsterdam wandelt, is het moeilijk voor te stellen dat onder de gebouwen, straten en grachten niet alleen veen maar ook veel andere grondsoorten voorkomen die een belangrijk stempel hebben gedrukt op de ontwikkeling van de stad. Hier ligt een aardkundige geschiedenis die enkele honderdduizenden jaren omvat. Landijs, rivieren, zee en wind hebben allemaal bijgedragen aan de vorming van een boeiende en afwisselende bodem, maar ook een bodem waarop het moeilijk wonen of bouwen is. Hoewel de geologische opbouw onder de stad natuurlijk niet direct zichtbaar is, zijn de afgeleide effecten hiervan vaak wel duidelijk. Maar men moet er op gewezen worden om ze te zien. Vandaar dit boekje. Al wandelend en lezend gaat er een aardkundige wereld voor u open waaruit blijkt dat de samenstelling van de ondergrond van Amsterdam grote invloed heeft gehad op zowel de vestiging en historische ontwikkeling van de stad als op het bouwen en wonen, door de eeuwen heen. -

De Drooglegging Van Amsterdam

DE DROOGLEGGING VAN AMSTERDAM Een onderzoek naar gedempt stadswater Jeanine van Rooijen, stageverslag 16 mei 1995. 1 INLEIDING 4 HOOFDSTUK 1: DE ROL VAN HET WATER IN AMSTERDAM 6 -Ontstaan van Amsterdam in het waterrijke Amstelland 6 -De rol en ontwikkeling van stadswater in de Middeleeuwen 6 -op weg naar de 16e eeuw 6 -stadsuitbreiding in de 16e eeuw 7 -De rol en ontwikkeling van stadswater in de 17e en 18e eeuw 8 -stadsuitbreiding in de 17e eeuw 8 -waterhuishouding en vervuiling 9 HOOFDSTUK 2: DE TIJD VAN HET DEMPEN 10 -De 19e en begin 20e eeuw 10 -context 10 -gezondheidsredenen 11 -verkeerstechnische redenen 12 -Het dempen nader bekeken 13 HOOFDSTUK 3: ENKELE SPECIFIEKE CASES 15 -Dempingen in de Jordaan in de 19e eeuw 15 -Spraakmakende dempingen in de historische binnenstad in de 19e eeuw 18 -De bouw van het Centraal Station op drie eilanden en de aanplempingen 26 van het Damrak -De Reguliersgracht 28 -Het Rokin en de Vijzelgracht 29 -Het plan Kaasjager 33 HOOFDSTUK 4: DE HUIDIGE SITUATIE 36 BESLUIT 38 BRONVERMELDING 38 BIJLAGE: -Overzicht van verdwenen stadswater 45 2 Stageverslag Geografie van Stad en Platteland Stageverlener: Dhr. M. Stokroos Gemeentelijk Bureau Monumentenzorg Amsterdam Keizersgracht 12 Amsterdam Cursusjaar 1994/1995 Voortgezet Doctoraal V3.13 Amsterdam, 16 mei 1995 DE DROOGLEGGING VAN AMSTERDAM een onderzoek naar gedempt stadswater Janine van Rooijen Driehoekstraat 22hs 1015 GL Amsterdam 020-(4203882)/6811874 Coll.krt.nr: 9019944 3 In de hier voor U liggende tekst staat het eeuwenoude thema 'water in Amsterdam' centraal. De stad heeft haar oorsprong, opkomst, ontplooiing, haar specifieke vorm en schoonheid, zelfs haar naam te danken aan een constante samenspraak met het water. -

Leefbaarheid En Veiligheid De Leefbaarheid En Veiligheid Van De Woonomgeving Heeft Invloed Op Hoe Amsterdammers Zich Voelen in De Stad

13 Leefbaarheid en veiligheid De leefbaarheid en veiligheid van de woonomgeving heeft invloed op hoe Amsterdammers zich voelen in de stad. De mate waarin buurtgenoten met elkaar contact hebben en de manier waarop zij met elkaar omgaan zijn daarbij van belang. Dit hoofdstuk gaat over de leefbaar- heid, sociale cohesie en veiligheid in de stad. Auteurs: Hester Booi, Laura de Graaff, Anne Huijzer, Sara de Wilde, Harry Smeets, Nathalie Bosman & Laurie Dalmaijer 150 De Staat van de Stad Amsterdam X Kernpunten Leefbaarheid op te laten groeien. Dat is het laagste Veiligheid ■ De waardering voor de eigen buurt cijfer van de Metropoolregio Amster- ■ Volgens de veiligheidsindex is Amster- is stabiel en goed. Gemiddeld geven dam. dam veiliger geworden sinds 2014. Amsterdammers een 7,5 als rapport- ■ De tevredenheid met het aanbod aan ■ Burgwallen-Nieuwe Zijde en Burgwal- cijfer voor tevredenheid met de buurt. winkels voor dagelijkse boodschap- len-Oude Zijde zijn de meest onveilige ■ In Centrum neemt de tevredenheid pen in de buurt is toegenomen en buurten volgens de veiligheidsindex. met de buurt af. Rond een kwart krijgt gemiddeld een 7,6 in de stad. ■ Er zijn minder misdrijven gepleegd in van de bewoners van Centrum vindt Alleen in Centrum is men hier minder Amsterdam (ruim 80.000 bij de politie dat de buurt in het afgelopen jaar is tevreden over geworden. geregistreerde misdrijven in 2018, achteruitgegaan. ■ In de afgelopen tien jaar hebben –15% t.o.v. 2015). Het aantal over- ■ Amsterdammers zijn door de jaren steeds meer Amsterdammers zich vallen neemt wel toe. heen positiever geworden over het ingezet voor een onderwerp dat ■ Slachtofferschap van vandalisme komt uiterlijk van hun buurt. -

Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020

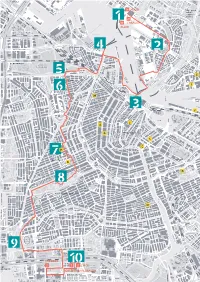

Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020 Aanscherping rondleidingenbeleid voor een leefbare binnenstad Inhoud 1 Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020 3 1.1 Wat is de definitie van een rondleiding? 4 1.2 Wat zijn de voorwaarden voor de ontheffing rondleidingen 2020? 4 1.3 Verbod op rondleidingen langs prostitutieramen 5 2 Achtergrond 6 3 Eerdere maatregelen voor groepsrondleidingen 7 4 Ervaren overlast door rondleidingen 8 4.1 Kwantitatief druktebeeld groepsrondleidingen 8 4.2 Druktebeeld in cijfers 9 4.3 Druktebeeld op kaart 10 4.4 Kwalitatief druktebeeld: ervaren overlast van groepsrondleidingen 11 4.5 Waarom geven groepen overlast? 12 5 Handhaving 13 5.1 Werkwijze handhaven op rondleidingen in stadsdeel Centrum 13 6 Monitoring en evaluatie 14 7 Participatie 15 2 1 Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020 Per 1 april 2020 wordt het ontheffingsbeleid uit 2018 voor rondleidingen aangescherpt. Ondanks eerder genomen maatregelen ervaren bewoners, ondernemers en sekswerkers nog altijd grote overlast van gidsgroepen. Het college wil de leefbaarheid in de binnenstad versterken en de overlast voor bewoners terugdringen. Om dit te bereiken zijn extra maatregelen nodig. Uit de uitspraak van 24 december 2019 blijkt dat de rechtbank Amsterdam Dit zijn redenen om nieuw beleid in te voeren, het vorige ontheffingenbeleid in waarbij geen ontheffing wordt verleend voor overeenstemming oordeelt met de het Wallengebied en waar voor de rest van vereisten die de Dienstenrichtlijn stelt. Het het centrum een ontheffing met voorschriften beschermen tegen overlast veroorzaakt wordt verstrekt. Het college meent dat ook door rondleidingen en het beschermen onderhavig ontheffingenbeleid aan de vereisten van de verkeersveiligheid zijn beide een van de Dienstenrichtlijn voldoet. Naast de dwingende reden van algemeen belang. -

Plan Van Aanpak Bestemmingsplan Hoofddorpplein-Schinkelbuurt 2021

Plan van aanpak Bestemmingsplan Hoofddorpplein-Schinkelbuurt 2021 Dagelijks Bestuur Stadsdeel Zuid 17 juli 2018 1 Aanleiding Het bestemmingsplan Hoofddorpplein-Schinkelbuurt is bijna 10 jaar oud. In de Wet ruimtelij- ke ordening is bepaald dat bestemmingsplannen elke 10 jaar moeten worden geactualiseerd. Daarom wordt er een nieuw bestemmingsplan Hoofddorpplein- Schinkelbuurt opgesteld. De actualisatie maakt onderdeel uit van de Actualisatieopgave Bestemmingsplan Amsterdam (hierna ABA) van het college. De ambitie van de gemeente Amsterdam is dat alle bestem- mingsplan voor de inwerkingtreding van de omgevingswet (2021) actueel en digitaal be- schikbaar zijn. Het doel van de ABA is om de actualisatie van (bijna) verouderde bestem- mingsplannen te versnellen zodat deze ambitie wordt gehaald. In het plangebied spelen een aantal ontwikkelingen. Deze worden toegelicht in de paragraaf ‘ontwikkelingen’. Met de actualisatie van dit bestemmingsplan wordt geanticipeerd op deze ontwikkelingen. Plangebied Het plangebied Hoofddorpplein-Schinkelbuurt heeft de volgende plangrenzen: • aan de noordzijde: het Surinameplein (tevens stadsdeelgrens met West) • aan de oostzijde: de Amstelveenseweg, waarbij de panden aan de oostzijde van de Amstelveenseweg tussen de Oranje Nassaulaan en de Sophialaan ook onderdeel uitma- ken van het plangebied • aan de zuidzijde: de Vaartstraat en de Rijnsburgstraat • aan de westzijde: de Westlandgracht (tevens stadsdeelgrens Nieuw West) De plangrenzen zijn aangeduid op kaart op pagina 3. Leeswijzer Dit plan van aanpak start met een beschrijving van het gebied. Daarna worden het doel en de uitgangspunten voor dit bestemmingsplan beschreven. Vervolgens wordt ingegaan op een aantal ontwikkelingen in het gebied en er wordt beschreven welke projecten er in voorberei- ding zijn. Vervolgens wordt ingegaan op de planning. Tenslotte wordt het participatietraject toegelicht. -

Detailhandelsbeleid 2018-2022 Sterke Winkelgebieden in Een Groeiende Stad 2 Detailhandelsbeleid Amsterdam 2018-2022 Inhoud

Detailhandelsbeleid 2018-2022 Sterke winkelgebieden in een groeiende stad 2 Detailhandelsbeleid Amsterdam 2018-2022 Inhoud Voorwoord 5 Samenvatting 7 1. Inleiding 17 1.1Waaromisbeleidvoordetailhandelnodig? 17 1.2Voorwieisditbeleid? 18 1.3Hoezithetmetgedanetoezeggingenopbasisvanhetvorigbeleid? 18 1.4HoeverhoudthetdetailhandelsbeleidzichtotdeOmgevingswet? 18 1.5WelkeafsprakenheeftAmsterdamgemaaktmetderegiogemeenten? 19 1.6Voorwelkeperiodegeldtditbeleid? 20 1.7Leeswijzer 20 2.Trends enontwikkelingendetailhandel 23 2.1Deeconomischebetekenisvandetailhandel 23 2.2Devraagnaardetailhandel 24 2.3Hetaanbodvandetailhandel 28 2.4Dewinkelstructuurenhetfunctionerenvandetailhandel 29 2.5Samenvattingvanaantalkwaliteiten,kansenenuitdagingenvoor Amsterdamalswinkelstad 34 3.Van ambitiesnaareen(gebiedsgerichte)visie 35 3.1Eenwinkelgebiedversterken:maatwerk,samenwerkingenintegraal 36 3.2Beleidsdoelstellingenvoordedetailhandel 37 3.3Eenspecifiekekoersvoordetailhandelinverschillendegebieden 39 3.4Visieopdetailhandelindekernzone:debinnenstaden Museumkwartier,samenhetkernwinkelgebied 40 3.5Visieopdedetailhandelindecentrumzone:de19e-envroeg 20e-eeuwsegordelvanWest,Zuid,Oost 45 3.6Visieopdetailhandelindestadszone:Nieuw-West,Noord,Zuidoost, Westpoort,Zuid(Buitenveldert),Houthavens,Amstelkwartier,Zuidas, Zeeburgereiland,OostelijkeEilanden,IJburgennoordelijkeIJ-oevers 49 3 4.Algemenebeleidsregelsvoorsterkewinkelgebieden 57 1 Meerdiversiteitinhetwinkelaanbod 57 2 Geenlosstaandewinkels,maareenclusteringvanhetwinkelaanbod inwinkelgebieden 57 3 Selectievegroeivanhetaantalwinkel(meter)stervoorkoming -

The Social Impact of Gentrification in Amsterdam

Does income diversity increase trust in the neighbourhood? The social impact of gentrification in Amsterdam Lex Veldboer & Machteld Bergstra, University of Amsterdam Paper presented at the RC21 Conference The Struggle to Belong: Dealing with Diversity in Twenty-first Century Urban Settings Session 10: Negotiating social mix in global cities Amsterdam, 7-9 July 2011 Lex Veldboer & Machteld Bergstra are researchers at the Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research, Kloveniersburgwal 48, 1012 CX Amsterdam [email protected] Does income diversity increase trust in the neighbourhood? The social impact of gentrification in Amsterdam Lex Veldboer & Machteld Bergstra, University of Amsterdam Abstract What happens when the residential composition of previously poor neighbourhoods becomes more socially mixed? Is the result peaceful co-existence or class polarization? In countries with neo-liberal policies, the proximity of different social classes in the same neighbourhood has led to tension and polarization. But what happens in cities with strong governmental control on the housing market? The current study is a quantitative and qualitative examination of how greater socio-economic diversity among residents affects trust in the neighbourhood in the Keynesian city of Amsterdam.1 Our main finding is that the increase of owner-occupancy in neighbourhoods that ten years ago mostly contained low-cost housing units has had an independent positive effect on neighbourhood trust. We further examined whether increased neighbourhood trust was associated with „mild gentrification‟ in two Amsterdam neighbourhoods. While this was partially confirmed, the Amsterdam model of „mild gentrification‟ is under pressure. 1 Amsterdam has a long tradition of public housing and rent controls. -

Mixed-Use Index), 44 Th ISOCARP Congress 2008

Joost W. van den Hoek, The MXI (Mixed-use Index), 44 th ISOCARP Congress 2008 The MXI (Mixed-use Index) an instrument for anti sprawl policy ? 1 Introduction It is commonly stated that societal change is one the driving forces for urban development and the definition of urban projects. In the 20 th century economy transformed from industrial production and distribution to knowledge based service and creation. The rapid development in modern times of economy and technology increased the scale of operating from a local to a global scale. During this “process of modernization” The physical presence of our urban configurations and networks has become both a product and a witness of these historical forces of change. This is exemplified in urban development by aspects like scale- enlargement and functional specialization. Take for instance a European city like Amsterdam and analyze a square mile of historic texture. One will see that within this historic texture there as many jobs as there are beds. Take the same square mile of 20 th century texture and most likely one will end up with counting only jobs or only beds as is shown in figure 1. Figure 1. Functional segregation and scale enlargement in urban history. Now that we are watching the deindustrialization of Western cities, in the Netherlands the segregation of a spatial and functional nature is a process that is still taking place at an increasing speed (Louw 2005). This is often explained along the lines of rudimentary “modernist” planning principals that as a matter of fact are a product of the industrial revolution. -

Mobiliteitsaanpak Amsterdam 2030 Vastgesteld Door De Gemeenteraad Op 13 Juni 2013 Inhoud

MobiliteitsAanpak Amsterdam 2030 vastgesteld door de Gemeenteraad op 13 juni 2013 Inhoud Wat zijn de ontwikkelingen? 11 Wat zijn de veranderingen in de mobiliteit? 17 Wat is de hoofdlijn van de nieuwe aanpak? 25 Wat is de uitwerking van maatregelen? 39 Wat zijn de kaders voor uitvoering? 53 Bijlage Plusnetten 59 Voorwoord Beste Amsterdammers, Hierbij presenteer ik u de MobiliteitsAanpak van Amsterdam. Hierin wordt geschetst hoe we Amsterdam ook in de toekomst bereikbaar willen houden en meer aandacht willen geven aan het verbeteren van de openbare ruimte. Dat is geen gemakkelijke opgave. Amsterdam is een stad waar op een relatief kleine oppervlakte veel mensen wonen, werken en recreëren. En Amsterdam blijft groeien. In 2040 is het aantal huishoudens in de regio toegenomen met circa 270.000. Keuzes maken en het zo optimaal mogelijk benutten van de ruimte en mogelijkheden is en blijft daarom van groot belang. Hoe kunnen we de Amsterdamse straten, de wegen en de OV-lijnen zo inrichten dat zoveel mogelijk mensen het snelst van A naar B kunnen reizen? Hoe kunnen we tegelijkertijd inspelen op een verdere kwaliteitsverbetering van de openbare ruimte? In de MobiliteitsAanpak staat wat we de komende jaren gaan doen om dit allemaal TEREALISEREN4ENAANZIENVANEENAANTALSPECIÚEKEPROBLEMENWORDTEENCONCRETE oplossingsrichting gevonden in de aparte beleidsstukken, zoals over het lokale OPENBAARVERVOER ÚETSENPARKEREN De MobiliteitsAanpak laat als overkoepelend beleidsstuk de samenhang zien tussen de deelonderwerpen en schetst het totaalplaatje voor de stad. Het vormt de basis voor het mobiliteitsbeleid van de komende jaren. Om de geschetste doelen te bereiken is de inzet van velen nodig. Van de Amsterdammer die elke dag zijn optimale manier van reizen kiest, van de bedrijven die meebepalen hoe hun personeel en goederen worden aangevoerd en van de vele bezoekers van ver en dichtbij die dagelijks gebruik maken van onze prachtige stad. -

Het Verkeer Verdeelt De Stad Tot Op Het Bot Ruimte, Doorstroming En Verbinden, Het Klinkt Goed Als Uitgangspunt Voor De Mo- Biliteit in De Drukte Van Amsterdam

Berichten uit de Westelijke Binnenstad Uitgave van De beleving van een kind A. van Wees distilleerderij De Ooievaar Dit blad biedt naast buurtinformatie Wijkcentrum Jordaan & Gouden Reael waarbij saamhorigheidsgevoel en begrip zich Op de uiterste noordwestpunt van de Jordaan, een platform waarop lezers hun visie op actuele jaargang 13 nummer 3 begon te ontwikkelen. De winnende staat al bijna 100 jaar A. van Wees distilleer- zaken kenbaar kunnen maken. Lees ook onze juni t/m augustus 2015 inzending van de verhalenwedstrijd derij De Ooievaar; de laatste ambachtelijke Webkrant: www.amsterdamwebkrant.nl de Jordaan door Henk de Hoogd Pagina 3 distilleerderij van Amsterdam Pagina 5 Haarlemmerbuurt Het verkeer verdeelt de stad tot op het bot Ruimte, doorstroming en verbinden, het klinkt goed als uitgangspunt voor de mo- biliteit in de drukte van Amsterdam. Maar schijn bedriegt: het verkeer verdeelt de stad tot op het bot. Een verkeersluwere Haarlemmerbuurt is goed voor de handel, zegt wethouder Pieter Litjens (VVD) die lof en kritiek oogstte. ‘Niet waar, dat kost omzet’, klinkt het uit de hoek van de Haarlemmerbuurtondernemers. T MI Amsterdam is gebouwd voor paard en wagen winkelstraatmanager Nel de Jager. Auto’s S en niet voor de 400.000 autobewegingen, en fietsers zijn nodig voor de klandizie. ‘De AN K J I 350.000 OV-reizigers en 1,1 miljoen fietsbe- Haarlemmerdijk is een boodschappenstraat. R wegingen, daarom wil Pieter Litjens wat aan Het is geen toeristengebied, zoals de Negen END het verkeer in de stad doen, zei hij half mei in Straatjes. Daar loop je alle straatjes door. De H O de Posthoornkerk aan de Haarlemmerstraat.