The Social Impact of Gentrification in Amsterdam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thuiswonende Tot -Jarige Amsterdammers

[Geef tekst op] - Thuiswonende tot -jarige Amsterdammers Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek | Thuiswonende tot - arigen in Amsterdam In opdracht van: stadsdeel 'uid Pro ectnummer: )*) Auteru: Lieselotte ,icknese -ester ,ooi ,ezoekadres: Oudezi ds .oorburgwal 0 Telefoon 1) Postbus 213, ) AR Amsterdam www.ois.amsterdam.nl l.bicknese6amsterdam.nl Amsterdam, augustus )* 7oto voorzi de: 8itzicht 9estertoren, fotograaf Cecile Obertop ()) Onderzoek, Informatie en Statistiek | Thuiswonende tot - arigen in Amsterdam Samenvatting Amsterdam telt begin )* 0.*2= inwoners met een leefti d tussen de en aar. .an hen staan er 03.0)3 ()%) ingeschreven op het woonadres van (een van) de ouders. -et merendeel van deze thuiswonenden is geboren in Amsterdam (3%). OIS heeft op verzoek van stadsdeel 'uid gekeken waar de thuiswonende Amsterdammers wonen en hoe deze groep is samengesteld. Ook wordt gekeken naar de kenmerken van de -plussers die hun ouderli ke woning recent hebben verlaten. Ruim een kwart van de thuiswonende tot -jarigen woont in ieuw-West .an de thuiswonende tot en met 0*- arige Amsterdammers wonen er *.=** (2%) in Nieuw- 9est. Daarna wonen de meesten in 'uidoost (2.)A )2% van alle thuiswonenden). De stadsdelen Noord en Oost tellen ieder circa 1.2 thuiswonenden ()1%). In 9est zi n het er circa 1. ()0%), 'uid telt er ruim .) ())%) en in Centrum gaat het om .) tot en met 0*- arigen (2%). In bi lage ) zi n ci fers opgenomen op wi k- en buurtniveau. Driekwart van alle thuiswonende tot en met 0*- arige Amsterdammers is onger dan 3 aar. In Nieuw-9est en Noord is dit aandeel wat hoger (==%), terwi l in 'uidoost thuiswonenden vaker ouder zi n dan 3 aar (0%). -

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam) 52° 21' 14" N 4° 55' 11"Archief E Philip Staal (http://toolserver.org/~geohack Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam)/geohack.php?language=nl& params=52_21_14.19_N_4_55_11.49_E_scale:6250_type:landmark_region:NL& pagename=Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam)) Uit Wikipedia, de vrije encyclopedie De Transvaalbuurt is een buurt van het stadsdeel Oost van de Transvaalbuurt gemeente Amsterdam, onderdeel van de stad Amsterdam in de Nederlandse provincie Noord-Holland. De buurt ligt tussen de Wijk van Amsterdam Transvaalkade in het zuiden, de Wibautstraat in het westen, de spoorlijn tussen Amstelstation en Muiderpoortstation in het noorden en de Linnaeusstraat in het oosten. De buurt heeft een oppervlakte van 38 hectare, telt 4500 woningen en heeft bijna 10.000 inwoners.[1] Inhoud Kerngegevens 1 Oorsprong Gemeente Amsterdam 2 Naam Stadsdeel Oost 3 Statistiek Oppervlakte 38 ha 4 Bronnen Inwoners 10.000 5 Noten Oorsprong De Transvaalbuurt is in de jaren '10 en '20 van de 20e eeuw gebouwd als stadsuitbreidingswijk. Architect Berlage ontwierp het stratenplan: kromme en rechte straten afgewisseld met pleinen en plantsoenen. Veel van de arbeiderswoningen werden gebouwd in de stijl van de Amsterdamse School. Dit maakt dat dat deel van de buurt een eigen waarde heeft, met bijzondere hoekjes en mooie afwerkingen. Nadeel van deze bouw is dat een groot deel van de woningen relatief klein is. Aan de basis van de Transvaalbuurt stonden enkele woningbouwverenigingen, die er huizenblokken -

Uitvoeringsprogramma Aanpak Binnenstad Onderscheidt 6 Prioriteiten Die Samen En in Wisselwerking Met Elkaar Bijdragen Aan De Opgaven in De Binnenstad

AANPAK BINNENSTAD Uitvoeringsprogramma december 2020 i. Inhoud 1. Vooraf 3 Van ambitie naar maatregelen 4 2. Aanleiding 5 3. Ambitie 6 4. Uitvoeringsprogramma 7 5. Opgaven 9 BINNENSTAD AANPAK Enkele voorbeelden van Aanpak Binnenstad 10 2 6. Maatregelen 11 6.1 Functiemenging en diversiteit 12 6.2 Beheer en handhaving 16 6.3 Een waardevolle bezoekerseconomie 20 6.4 Versterken van de culturele verscheidenheid en buurtidentiteiten 23 6.5 Bevorderen van meer en divers woningaanbod 26 6.6 Meer verblijfsruimte en groen in de openbare ruimte 29 7. Organisatie en financiën 32 8. Samenwerking en voortgang 33 UITVOERINGSPROGRAMMA 1. Vooraf In mei 2020 is in een raadsbrief de Aanpak Binnenstad gelanceerd. Deze aanpak combineert maatregelen en visie voor zowel de korte als langere termijn, formuleert de opgaven in de binnenstad breed en in samenhang, maar stelt tegelijkertijd ook prioriteiten. Deze aanpak bouwt voort op dat wat is ingezet door de gemeente en tal van anderen rond de binnenstad, maar maakt waar nodig ook scherpe keuzes. En deze aanpak pakt problemen aan én biedt perspectief. Wat ons treft in de vele gesprekken die Een deel van deze maatregelen is reeds De kracht van een set maatregelen is dat wij in de afgelopen maanden gevoerd in gang gezet, want we beginnen niet bij ze goed te adresseren en concreet zijn. hebben met bewoners, ondernemers, nul. Andere maatregelen nemen wij in De kwetsbaarheid is dat ze een zekere vastgoedeigenaren en culturele onderzoek of voorbereiding en met weer mate van uitwisselbaarheid suggereren. instellingen, is dat er een breed gedragen andere starten wij in het kader van dit Dat laatste willen wij weerleggen. -

A B N N N Z Z Z C D E F G H I J K

A8 COENTUNNELWEG W WEG ZIJKANAAL G AMMERGOU G R O 0 T E Gemeente Zaanstad D N M E E R Gemeente Oostzaan K L E I N E AA V A N B BOZEN M E E R NOORDER BOS LANDSMEER E EKSTRAA SYMON SPIERSWEG V E E R MEERTJE T ZUIDEINDE AFRIKAHAVEN NOORDER-IJPLAS NOOR : BAARTHAVEN D ZEE ISAAC KAN Broekermeerpolder NOORDERWEG AAL ( IN AANLEG ) K N O O P P U N T ZUIDEINDE DORS MACHINEWEG RUIGOORD ZAANDAM C O E N P L E I N WIM ARKEN AE THOMASSENHAVEN HET SCHOUW Volgermeer- Gemeente Waterland SPORTPARK R M EER EN W E G BR OEKE Belmermeerpolder RINGWEG-NOO MIDD Hemspoortunnel OOSTZANER- polder Houtrak- WERF DIRK KADOELENWEG polder R D Gemeente Landsmeer RIJPERWEG METSELAARHAVEN A 1 0 SWEG AMERIKAHAVEN R OOSTZANERWERF H e m p o n t ENAA STELLINGWEG MOL S T R A A T SPORTPARK STEN T OR MELKWEG UITDAM O O TW B EG ANKERWEG W E G RUIJGOORDWEG WESTHAVENWEG STOOM KADOELEN BROEKERGOUW TER A M D M Burkmeer- ER STELLINGWEG UIT D IE ELBAWEG C A R L R E AVEN SLOCH Veenderij H Windturbine IJNI HORNWEG ERSH polder V o e t v e e r CACAO AVEN KADO SPORTPARK Grote Blauwe Polder KOMETENSINGEL Sportpark Zunderdorp E R R.I. Groote OT DIE LANDS ELENWEG TUINDORP KADOELEN LATEXWEG IJpolder METEORENWEG Tuindorp AAL SL NOORDERBREEDTE N WESTHAVEN OOSTZAAN KA COENTUNNEL CORNELIS DOUWESWEG Oostzaan MIDDENWEG MEERDER JAN VAN RIEBEECK G O U W HOLY KOFFIEWEG RUIGOORD MIDDENWEG RUIGOORD PETROLEUM HOLLANDSCH HOLYSLOOT DIJK NDAMMER HAVEN NOORD E : INCX POPP AUSTRALIEHA V E N ZIJKANAAL I POMONASTRAAT NWEG HORNWEG WESTERLENGTE RWEG OCEANE USSEL A N A N A S HAVEN NIEUWE HEMWEG P L E I N BUIKSLOOT RDE R.I. -

Belonging in the Kinkerbuurt a Qualitative Study on Feeling at Home and Place Making in a Gentrifying Neighbourhood

Belonging in the Kinkerbuurt A qualitative study on feeling at home and place making in a gentrifying neighbourhood © Carly Wollaert, 2017 Nathalie Sijbrands 10553789 Master Sociology, Track: Urban Sociology 08-07-2019 Word count: 18889 Supervisor: mw. dr. L.J. (Linda) van de Kamp Second reader: mw. dr. O.A. (Adeola) Enigbokan University of Amsterdam Master Thesis Urban Sociology Table of Contents BELONGING IN THE CHANGING KINKERBUURT ............................................................ 3 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 6 2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ...................................................................................... 9 2.1 GENTRIFICATION ......................................................................................................................................... 9 State-led gentrification and social mixing in Amsterdam ................................................................ 10 Role of consumption in gentrification ..................................................................................................... 12 Authenticity and branding .......................................................................................................................... 13 2.2 BELONGING: FEELING AT HOME AND DOING PLACE ............................................................................... 15 Definitions of belonging .............................................................................................................................. -

Amsterdam City Index 2018

A M S T E R D A M C &% T Y &% N D E X 2 0 1 8 AMSTERDAM CITY INDEX 2018 en de Stem van de Amsterdamse Ondernemer UITGAVE VAN VERENIGING AMSTERDAM CITY JANUARI 2018 AMSTERDAM CITY INDEX N°10 2018 5 Voorwoord van de voorzitter J Indexcijfer per 1 januari 2018 ED Omzet EF Schoon, veilig en bereikbaar FD inhoud De stem van de ondernemer FL Bewoners, bedrijven, bezoekers en imago GL Verantwoording HH Definities van de 26 trends HK Lid worden van Amsterdam City IH Colofon IJ DJ AMSTERDAM CITY INDEX N°ED FDEL “De st;d heeft een groot gebrek ;;n reinigend vermogen l;ten zien. Dus zeggen wij: overheid voorwoord doe je werk.” AMSTERDAM CITY INDEX N°10 2018 0L et genoegen presenteren wij u de Amsterdam City Index 2018, Mde barometer van de bedrijvige binnenstad, of beter: van Amsterdam Centrum XL. Alle lichten lijken op groen te staan. Er is jubel en hosanna over hoe goed het ons economisch weer gaat. De Amsterdam City Index reflec- teert die vreugde en dat optimisme. De City Index stijgt van 120 vorig jaar naar nu 122. Het gaat best goed in en om Amsterdam. Veel indicatoren staan in de plus. Er zijn grote en grootste plannen voor een groter Amsterdam. Het positieve gevoel neemt nog toe als we ons realiseren dat de City Index 2018 eigenlijk nog hoger had kunnen staan. De City Index laat echter ook een aantal indicatoren zien die het minder doen en de uitkomst dus drukken. Het managen van de groei Groei is goed, vinden wij. -

DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM Een Geologische Stadswandeling

EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans OVER DE AUTEUR Dr. Wim de Gans (Amersfoort, 1941) studeerde aardwetenschappen aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na zijn afstuderen was hij als docent achtereenvolgens verbonden aan de Rijks Universiteit Groningen en de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Na deze universitaire loopbaan was hij jaren lang werkzaam als districtsgeoloog bij de Rijks Geologische Dienst (RGD), die in 1997 is overgegaan naar TNO. De schrijver is bij TNO voor de Geologische Dienst Nederland vooral bezig met het populariseren van de geologie van Nederland. Hij schreef talrijke publicaties en enkele boeken waaronder het Geologieboek Nederland (ANWB/TNO). DE BODEM ONDER AMSTERDAM EEN GEOLOGISCHE STADSWANDELING Wim de Gans VOORWOORD Wanneer je door de binnenstad van Amsterdam wandelt, is het moeilijk voor te stellen dat onder de gebouwen, straten en grachten niet alleen veen maar ook veel andere grondsoorten voorkomen die een belangrijk stempel hebben gedrukt op de ontwikkeling van de stad. Hier ligt een aardkundige geschiedenis die enkele honderdduizenden jaren omvat. Landijs, rivieren, zee en wind hebben allemaal bijgedragen aan de vorming van een boeiende en afwisselende bodem, maar ook een bodem waarop het moeilijk wonen of bouwen is. Hoewel de geologische opbouw onder de stad natuurlijk niet direct zichtbaar is, zijn de afgeleide effecten hiervan vaak wel duidelijk. Maar men moet er op gewezen worden om ze te zien. Vandaar dit boekje. Al wandelend en lezend gaat er een aardkundige wereld voor u open waaruit blijkt dat de samenstelling van de ondergrond van Amsterdam grote invloed heeft gehad op zowel de vestiging en historische ontwikkeling van de stad als op het bouwen en wonen, door de eeuwen heen. -

De Drooglegging Van Amsterdam

DE DROOGLEGGING VAN AMSTERDAM Een onderzoek naar gedempt stadswater Jeanine van Rooijen, stageverslag 16 mei 1995. 1 INLEIDING 4 HOOFDSTUK 1: DE ROL VAN HET WATER IN AMSTERDAM 6 -Ontstaan van Amsterdam in het waterrijke Amstelland 6 -De rol en ontwikkeling van stadswater in de Middeleeuwen 6 -op weg naar de 16e eeuw 6 -stadsuitbreiding in de 16e eeuw 7 -De rol en ontwikkeling van stadswater in de 17e en 18e eeuw 8 -stadsuitbreiding in de 17e eeuw 8 -waterhuishouding en vervuiling 9 HOOFDSTUK 2: DE TIJD VAN HET DEMPEN 10 -De 19e en begin 20e eeuw 10 -context 10 -gezondheidsredenen 11 -verkeerstechnische redenen 12 -Het dempen nader bekeken 13 HOOFDSTUK 3: ENKELE SPECIFIEKE CASES 15 -Dempingen in de Jordaan in de 19e eeuw 15 -Spraakmakende dempingen in de historische binnenstad in de 19e eeuw 18 -De bouw van het Centraal Station op drie eilanden en de aanplempingen 26 van het Damrak -De Reguliersgracht 28 -Het Rokin en de Vijzelgracht 29 -Het plan Kaasjager 33 HOOFDSTUK 4: DE HUIDIGE SITUATIE 36 BESLUIT 38 BRONVERMELDING 38 BIJLAGE: -Overzicht van verdwenen stadswater 45 2 Stageverslag Geografie van Stad en Platteland Stageverlener: Dhr. M. Stokroos Gemeentelijk Bureau Monumentenzorg Amsterdam Keizersgracht 12 Amsterdam Cursusjaar 1994/1995 Voortgezet Doctoraal V3.13 Amsterdam, 16 mei 1995 DE DROOGLEGGING VAN AMSTERDAM een onderzoek naar gedempt stadswater Janine van Rooijen Driehoekstraat 22hs 1015 GL Amsterdam 020-(4203882)/6811874 Coll.krt.nr: 9019944 3 In de hier voor U liggende tekst staat het eeuwenoude thema 'water in Amsterdam' centraal. De stad heeft haar oorsprong, opkomst, ontplooiing, haar specifieke vorm en schoonheid, zelfs haar naam te danken aan een constante samenspraak met het water. -

Leefbaarheid En Veiligheid De Leefbaarheid En Veiligheid Van De Woonomgeving Heeft Invloed Op Hoe Amsterdammers Zich Voelen in De Stad

13 Leefbaarheid en veiligheid De leefbaarheid en veiligheid van de woonomgeving heeft invloed op hoe Amsterdammers zich voelen in de stad. De mate waarin buurtgenoten met elkaar contact hebben en de manier waarop zij met elkaar omgaan zijn daarbij van belang. Dit hoofdstuk gaat over de leefbaar- heid, sociale cohesie en veiligheid in de stad. Auteurs: Hester Booi, Laura de Graaff, Anne Huijzer, Sara de Wilde, Harry Smeets, Nathalie Bosman & Laurie Dalmaijer 150 De Staat van de Stad Amsterdam X Kernpunten Leefbaarheid op te laten groeien. Dat is het laagste Veiligheid ■ De waardering voor de eigen buurt cijfer van de Metropoolregio Amster- ■ Volgens de veiligheidsindex is Amster- is stabiel en goed. Gemiddeld geven dam. dam veiliger geworden sinds 2014. Amsterdammers een 7,5 als rapport- ■ De tevredenheid met het aanbod aan ■ Burgwallen-Nieuwe Zijde en Burgwal- cijfer voor tevredenheid met de buurt. winkels voor dagelijkse boodschap- len-Oude Zijde zijn de meest onveilige ■ In Centrum neemt de tevredenheid pen in de buurt is toegenomen en buurten volgens de veiligheidsindex. met de buurt af. Rond een kwart krijgt gemiddeld een 7,6 in de stad. ■ Er zijn minder misdrijven gepleegd in van de bewoners van Centrum vindt Alleen in Centrum is men hier minder Amsterdam (ruim 80.000 bij de politie dat de buurt in het afgelopen jaar is tevreden over geworden. geregistreerde misdrijven in 2018, achteruitgegaan. ■ In de afgelopen tien jaar hebben –15% t.o.v. 2015). Het aantal over- ■ Amsterdammers zijn door de jaren steeds meer Amsterdammers zich vallen neemt wel toe. heen positiever geworden over het ingezet voor een onderwerp dat ■ Slachtofferschap van vandalisme komt uiterlijk van hun buurt. -

Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020

Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020 Aanscherping rondleidingenbeleid voor een leefbare binnenstad Inhoud 1 Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020 3 1.1 Wat is de definitie van een rondleiding? 4 1.2 Wat zijn de voorwaarden voor de ontheffing rondleidingen 2020? 4 1.3 Verbod op rondleidingen langs prostitutieramen 5 2 Achtergrond 6 3 Eerdere maatregelen voor groepsrondleidingen 7 4 Ervaren overlast door rondleidingen 8 4.1 Kwantitatief druktebeeld groepsrondleidingen 8 4.2 Druktebeeld in cijfers 9 4.3 Druktebeeld op kaart 10 4.4 Kwalitatief druktebeeld: ervaren overlast van groepsrondleidingen 11 4.5 Waarom geven groepen overlast? 12 5 Handhaving 13 5.1 Werkwijze handhaven op rondleidingen in stadsdeel Centrum 13 6 Monitoring en evaluatie 14 7 Participatie 15 2 1 Ontheffingsbeleid Rondleidingen 2020 Per 1 april 2020 wordt het ontheffingsbeleid uit 2018 voor rondleidingen aangescherpt. Ondanks eerder genomen maatregelen ervaren bewoners, ondernemers en sekswerkers nog altijd grote overlast van gidsgroepen. Het college wil de leefbaarheid in de binnenstad versterken en de overlast voor bewoners terugdringen. Om dit te bereiken zijn extra maatregelen nodig. Uit de uitspraak van 24 december 2019 blijkt dat de rechtbank Amsterdam Dit zijn redenen om nieuw beleid in te voeren, het vorige ontheffingenbeleid in waarbij geen ontheffing wordt verleend voor overeenstemming oordeelt met de het Wallengebied en waar voor de rest van vereisten die de Dienstenrichtlijn stelt. Het het centrum een ontheffing met voorschriften beschermen tegen overlast veroorzaakt wordt verstrekt. Het college meent dat ook door rondleidingen en het beschermen onderhavig ontheffingenbeleid aan de vereisten van de verkeersveiligheid zijn beide een van de Dienstenrichtlijn voldoet. Naast de dwingende reden van algemeen belang. -

Fact Sheet Leefbaarheidsindex Periode 2010-2012

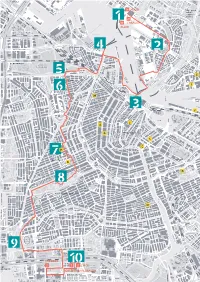

Fact sheet Leefbaarheidsindex Periode 2010-2012 nummer 3 | februari 2013 Deze fact sheet gaat in op de leefbaarheid van buurten in Amsterdam. Ontwikkelingen vanaf 2010 komen aan de orde, met specifieke aandacht voor de verandering tussen 2011 en 2012. De leefbaarheid in Amsterdam is tussen 2010 en 2012 licht verbeterd. Tussen 2011 en 2012 is de leefbaarheid op vergelijkbaar niveau gebleven. Bewoners in de stadsdelen Centrum, Nieuw-West en Noord beoordelen in 2012 de leefbaarheid het slechtste. Bewoners van Zuid en Zuidoost beoordelen de leefbaarheid juist beter dan gemiddeld het geval is. Een openbare ruimte die schoon, heel en veilig is hun buurt ervaren, oftewel het gaat om een draagt bij aan het verminderen van gevoelens van subjectieve index. onveiligheid. Om deze reden is in het Programakkoord Amsterdam 2010-2014 opge- Het bronjaar van de leefbaarheidsindex is 2010 nomen dat de leefbaarheid van Amsterdamse (oftewel de index is in 2010 op 100 gezet). De buurten gemonitord moet worden met een scores op de 24 verschillende indicatoren zijn leefbaarheidsindex. Op verzoek van de direc- per indicator geïndexeerd door te delen door tie Openbare Orde en Veiligheid (OOV) van de de gemiddelde waarde in 2010.1 De indexcijfers gemeente Amsterdam heeft O+S deze leefbaar- worden per buurt gepresenteerd met toevoe- heidsindex ontworpen. De leefbaarheidsindex ging van de kleuren rood, oranje, lichtgroen en bestaat uit drie deelindexen, die elk uit acht donkergroen. Deze kleuren laten zien hoe de indicatoren bestaan (zie tabel 1). De indicatoren leefbaarheid van de buurt zich verhoudt tot de komen uit de Veiligheidsmonitor Amsterdam- gemiddelde buurt in Amsterdam in 2010. -

Neighbourhood Liveability and Active Modes of Transport the City of Amsterdam

Neighbourhood Liveability and Active modes of transport The city of Amsterdam ___________________________________________________________________________ Yael Federman s4786661 Master thesis European Spatial and Environmental Planning (ESEP) Nijmegen school of management Thesis supervisor: Professor Karel Martens Second reader: Dr. Peraphan Jittrapiro Radboud University Nijmegen, March 2018 i List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... ii Acknowledgment .................................................................................................................................... ii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Liveability, cycling and walking .............................................................................................. 2 1.2. Research aim and research question ..................................................................................... 3 1.3. Scientific and social relevance ............................................................................................... 4 2. Theoretical background ................................................................................................................. 5 2.1.