Mixed-Use Index), 44 Th ISOCARP Congress 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

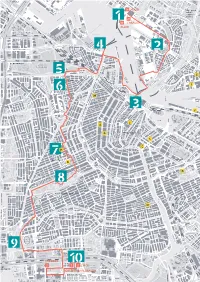

Waterpilot Zuidoostlob | Jan 2009 Zoektocht Naar De Rol Van Ontwerpen Met Water Op Het Grensvlak Van Stad En Land

Waterpilot Zuidoostlob | jan 2009 Zoektocht naar de rol van ontwerpen met water op het grensvlak van stad en land Sterk Water! Waterpilot Zuidoostlob Zoektocht naar de rol van ontwerpen met water op het grensvlak van stad en land Colofon Deze studie is tot stand gekomen dankzij bijdragen van: Projectgroep DRO/Waternet de ministeries van VROM, V & W en OCW Eric van der Kooij (DRO) de Dienst Ruimtelijke Ordening Amsterdam Arjen Grent (Waternet) Waternet / Hoogheemraadschap Amstel, Gooi en Vecht Geert Timmermans (DRO) TU Delft, leerstoel landschapsarchitectuur Carolin Wrana (DRO) En komt voor uit het Actieprogramma Ruimte en Cultuur Ellen Monchen (DRO) Bestuurlijk Overleg Platform Met bijdragen van Mevr. L. Garming - Hoogheemraadschap Amstel, Gooi en Vecht Robbert Heit, Paul Lakenman, Stephanie Wong, Yael Breimer, Erwin Dhr. Maarten van Poelgeest - wethouder ruimtelijke ordening en water, Folkers, Camiel van Drimmelen (allen DRO), Hermine van der Hiderlan- Gemeente Amsterdam den (VROM). Dhr. R. Grondel - wethouder groen en water, Gemeente Diemen Bijzondere dank gaat uit naar Eva de Graaf die de onderzoeksresultaten Dhr. W. Pieterman - wethouder ruimtelijke ordening en water, Gemeente van haar afstudeeropgave beschikbaar stelde voor deze rapportage. Ouderamstel Mevr. S. Ceha – portefeuillehouder ruimtelijk beheer, Stadsdeel Oost- Lay-out en vormgeving Watergraafsmeer Bart de Vries, DRO Mevr. E. Verdonk, portefeuillehouder ruimtelijke ordening, Stadsdeel Zuidoost Druk Drukkerij De Raat & De Vries, Amsterdam Stuurgroep Eric van der Kooij, projectleider Oplage Geert Timmermans (DRO) 500 stuks Inge Bobbink, Steffen Nijhuis (TUDelft, Faculteit Bouwkunde / Landschapsarchitectuur) Informatie Jan Elsinga (VROM) Eric van der Kooij Oswald Lagendijk (Deltares) [email protected] Paulien Hartog (Waternet) Paulien Hartog Pim Vermeulen (DRO) [email protected] Inhoudsopgave 3. -

Distributieve Onderbouwing En Effectanalyse Supermarkt Eerste Oosterparkstraat (Amsterdam)

Distributieve onderbouwing en effectanalyse supermarkt Eerste Oosterparkstraat (Amsterdam) 10 juni 2014 Eindrapport Status: Eindrapport Datum: 10 juni 2014 Een product van: Bureau Stedelijke Planning bv Silodam 1E 1013 AL Amsterdam 020 - 625 42 67 www.stedplan.nl [email protected] Team Detailhandel en Leisure: Drs. Gijs Foeken Drs. Toine Hooft Voor meer informatie: Toine Hooft, [email protected] In opdracht van: Van Riezen & Partners De in dit document verstrekte informatie mag uitsluitend worden gebruikt in het kader van de opdracht waarvoor deze is opgesteld. Elk ander gebruik behoeft de voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van Bureau Stedelijke Planning BV©. Projectnummer: 2013.A.600 Referentie: 2013.A.600 Van Riezen, Amsterdam Eerste Oosterparkstraat_100514 pagina 2 Inhoudsopgave Pagina Inleiding 4 1 Contextanalyse 5 1.1 Omvang en samenstelling draagvlak 1.2 Winkelstructuur en krachtenveld 1.3 Trends en ontwikkelingen 1.4 Eerste oordeelsvorming 2 Distributieve toets 13 2.1 Project Eerste Oosterparkstraat 2.2 Distributieve mogelijkheden en actuele behoefte 2.3 Ruimtelijk-kwalitatieve toets 2.4 Conclusie 3 Effecten 18 3.1 Ruimtelijk-economische impuls 3.2 Effecten op de bestaande detailhandelsstructuur 3.3 Effect op leegstand en woon-, leef- en ondernemersklimaat 3.4 Conclusie pagina 3 Inleiding Woningcorporatie Stadgenoot herontwikkelt de panden aan de Eerste Oosterparkstraat 88-126. Daarbij is afgesproken dat de bestaande negentiende-eeuwse straatgevel wordt teruggebouwd. Er komen 13 sociale huurappartementen. Daarnaast worden er 26 koopappartementen gebouwd. Op de begane grond komt een supermarkt van 1.100 m² en 1.000 m² bvo aan commerciële (winkel)ruimte, verdeeld over zes winkelunits die onderling zijn samen te voegen tot maximaal twee units. -

B U U Rtn Aam Gem Een Ten Aam Aan Tal B Ew O N Ers to Taal Aan Tal B

buurtnaam gemeentenaam totaal aantalbewoners onvoldoende zeer aantalbewoners onvoldoende ruim aantalbewoners onvoldoende aantalbewoners zwak aantalbewoners voldoende aantalbewoners voldoende ruim aantalbewoners goed aantalbewoners goed zeer aantalbewoners uitstekend aantalbewoners score* zonder aantalbewoners onvoldoende zeer bewoners aandeel onvoldoende ruim bewoners aandeel onvoldoende bewoners aandeel zwak bewoners aandeel voldoende bewoners aandeel voldoende ruim bewoners aandeel goed bewoners aandeel goed zeer bewoners aandeel uitstekend bewoners aandeel score* zonder bewoners aandeel Stommeer Aalsmeer 6250 0 0 350 1000 1400 2750 600 100 0 100 0% 0% 5% 16% 22% 44% 9% 2% 0% 2% Oosteinde Aalsmeer 7650 0 0 50 150 100 2050 3050 2050 200 0 0% 0% 1% 2% 1% 27% 40% 27% 3% 0% Oosterhout Alkmaar 950 0 0 50 500 100 250 0 0 0 0 0% 0% 8% 54% 9% 29% 0% 0% 0% 0% Overdie-Oost Alkmaar 3000 0 1700 1100 200 0 0 0 0 0 0 0% 56% 37% 7% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% Overdie-West Alkmaar 1100 0 0 100 750 250 50 0 0 0 0 0% 0% 8% 65% 21% 5% 0% 0% 0% 0% Ossenkoppelerhoek-Midden- Almelo 900 0 0 250 650 0 0 0 0 0 0 0% 0% 28% 72% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 1% Zuid Centrum Almere-Haven Almere 1600 0 250 150 200 150 500 100 50 250 0 0% 15% 10% 13% 9% 31% 6% 2% 15% 0% De Werven Almere 2650 50 100 250 800 450 1000 50 0 0 0 2% 3% 9% 30% 17% 38% 1% 0% 0% 0% De Hoven Almere 2400 0 150 850 700 50 250 250 150 50 0 0% 7% 35% 29% 1% 11% 10% 6% 2% 0% De Wierden Almere 3300 0 0 200 2000 500 450 150 50 0 0 0% 0% 5% 61% 15% 14% 4% 1% 0% 0% Centrum Almere-Stad Almere 4100 0 0 500 1750 850 900 100 0 -

Organisatie Welzijnsfuncties Oost/Watergraafsmeer

Organisatie Welzijnsfuncties Oost/Watergraafsmeer Globale inventarisatie en suggesties Amsterdam, 21 maart 2001 Herman Groen Frits ter Bruggen Paul van Soomeren Inhoudsopgave 1 Inleiding 3 1.1 Aanleiding 3 1.2 Verantwoording 4 2 Globale inventarisatie ('Houtskoolschets' ) 6 2.1 Enkele algemene gegevens 6 2.1 Aanbod menskracht en middelen 7 2.3 Minderheden en allochtone zelforganisaties 8 2.4 Kinderopvang 10 2.5 Speeltuinwerk 11 2.6 Tiener- en jongerenwerk 12 2.7 Sportbuurtwerk 13 2.8 Samenlevingsopbouw 13 2.9 Ouderenwerk 15 3 Samenvatting, conclusies en aandachtspunten 17 3.1 Inleiding 17 3.2 Algemene demografische tendensen 17 3.3 Diversiteit, spreiding en overlap 18 3.4 Witte plekken 18 3.5 'Verkleuring' 20 3.6 'Vergrijzing' 21 3.7 Commerciële tendensen 22 3.8 Ontmoeting, recreatie en tijdsbesteding 22 3.9 Samenlevingsopbouw 24 3.1 0 Beleid en kerntaken van de overheid 24 4 Suggesties 26 4.1 Inleiding 26 4.2 Eén nieuwe organisatie 26 4.3 Aanvullende argumenten bij de keuze voor één nieuwe organisatie 27 4.4 Het vraagstuk van de allochtone zelforganisaties 29 4.5 Het vraagstuk van de zorg 29 4.6 Suggesties voor een buurtgerichte aanpak 30 4.7 Draagvlak 30 Bijlagen Bijlage 1 Hoofdlijnen visie stadsdeel t.a.v. welzijnsfuncties 33 Bijlage 2 Hoofdlijnen diversiteitbeleid gemeente Amsterdam 35 Bijlage 3 Mogelijkheden en grenzen buurtgerichte aanpak 37 Bijlage 4 Geraadpleegde literatuur en rapportages 39 Pagina 2 Organisatie Welzijnsfuncties OostlWatergraafsmeer DSP - Amsterdam 1 Inleiding 1.1 Aanleiding Stadsdeel Oost/Watergraafsmeer beoogt de gesubsidïeerde functies en taken op het terrein van welzijn en zorg effectiever en efficiënter te organiseren, zodat sociale verbanden in het stadsdeel versterkt kunnen worden en een probleemgerichte aanpak kan worden gerealiseerd. -

SMART OFFICES from a Little Spark May Burst a Flame

SMART OFFICES From a little Spark may burst a flame. Dante Alighieri 1 Reinvented for the future A good office is ready for the future. It offers all the comfort needed to enable people to be the best that they can be – not just today, but also tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. Welcome to Spark Amsterdam – Smart Offices. In every aspect of Spark, ranging from the architecture through high-tech amenities to services and sustainability, the pivotal focus is on the comfort, convenience and well- being of the users. Efficient and flexible design, customized to meet every tenant’s needs; that is what is reflected in the added value this office building offers you and your associates and staff. Spark is located in a dynamic area, at the edge of the city centre, in easy reach of a hub of motorways and public transport networks, making it easily accessible by car and public transport connections to the city centre and the rest of the Netherlands. 2 3 Amsterdam Highly connected city Amsterdam is the capital and the financial business national Airport Schiphol, Amsterdam is a highly attrac- as well as growing companies and large, reputable cor- centre of the Netherlands, a trading city with a rich his- tive business location. porations. Additional advantages include the presence tory, numerous multinational corporation headquarters and easy accessibility of networks, the presence of and financial services companies, and a breeding ground Amsterdam is the place where entrepreneurs go to leading research and educational institutes in and for innovative start-ups. Situated at a crossroads of road, make their dreams come true and their ideas come to around the city, and the vibrant residential, commercial waterway, railway and airline connections, and the inter- fruition. -

Highrise – Lowland

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Highrise – Lowland Author: Pi de Bruijn, Partner, de Architekten Cie Subjects: Building Case Study Urban Design Keywords: Urban Habitat Verticality Publication Date: 2004 Original Publication: CTBUH 2004 Seoul Conference Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Pi de Bruijn Highrise – Lowland Pi de Bruijn Ir, Master of Architecture Partner in de Architekten Cie, Amsterdam, Netherlands Abstract High-rise in the Netherlands, lowland par excellence, could there be a greater contrast? In a country dominated by water and often by low roofs of cloud, high-rise construction is almost by definition a Statement. Perhaps this is the reason why it has been such a controversial topic for so long, with supporters and opponents assailing one another with contrasting ideas on urban development and urbanism. Particularly in historical settings, these ‘new icons’ were long regarded as an erosion of our historical legacy, as big- business megalomania. Such a style does not harmonize with this cosy, homely country, it was maintained, with its consultative structures and penchant for regulation. Moreover, high-rise construction hardly ever took place anyway because there were infinitely more opportunities for opponents to apply delaying tactics than there were for proponents to deploy means of acceleration, and postponement soon meant abandonment. Nevertheless, a turning point now seems to have been reached. Everyone is falling over one another to allow architectonic climaxes determine the new urban identity. Could it be more inconsistent? In order to discover the origins of the almost emotional resistance to high-rise construction and why attitudes have changed, we shall first examine the physical conditions and the socio-economic context of the Netherlands. -

Driemond Bij Stadsgebied Weesp?

Jaargang 53, extra editie Uitgave van Stichting Dorpsraad Driemond Driemond bij stadsgebied Weesp? In de komende maanden wordt onderzocht of Driemond, onder de worden. Driemond vormt een essentiële noemer van nabijheid van bestuur, wil en kan aansluiten bij het nieuw verbinding tussen Weesp en Amsterdam. De bestuursorganisatie van een nieuw te vormen stadsgebied Weesp. Op 14 September a.s. om 20.00 stadsgebied Weesp-Driemond is een experi- uur organiseert de Dorpsraad Driemond een discussieavond voor alle ment van 3 jaren. In die tijd dient de nieuwe bewoners van Driemond in de sporthal van MatchZo. Voor deze bestuursorganisatie zich te bewijzen. Voor Driemond, dat al zo is ingebed in Amster- avond is een Corona protocol van kracht. Mede in verband met het dam, vormt zo’n experiment ook een risico. aantal zitplaatsen op 1,5 meter afstand, wordt u verzocht zich tijdig Er moet wel sprake zijn van een daadwerke- vooraf aan te melden: 0294- 414 883 of [email protected]. lijke verbetering in de afstand tussen bewo- ners en bestuur. Het is niet de bedoeling dat Ter voorbereiding, heeft de Dorpsraad Driemond het hier volgend Driemond tijdens of na het 3 jaar durende discussiestuk opgesteld waarin kernwaarden voor Driemond vermeld bestuursexperiment juist zeggenschap staan. Reacties op dit discussiestuk kunt u geven in persoon op de inlevert. Bovenal is het ook van belang dat Weesp zich uitspreekt voor een gezamenlijk 14de September of per telefoon of email voor de bijeenkomst. stadsgebied met Driemond. Voorstel Dorpsraad ten aanzien van bestuur. Maar de belangen van Driemond Concept kernwaarden van Driemond condities aansluiting dienen geborgd te zijn als volwaardige part- ner in het nieuwe stadsgebied. -

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia

Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam) - Wikipedia http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam) 52° 21' 14" N 4° 55' 11"Archief E Philip Staal (http://toolserver.org/~geohack Transvaalbuurt (Amsterdam)/geohack.php?language=nl& params=52_21_14.19_N_4_55_11.49_E_scale:6250_type:landmark_region:NL& pagename=Transvaalbuurt_(Amsterdam)) Uit Wikipedia, de vrije encyclopedie De Transvaalbuurt is een buurt van het stadsdeel Oost van de Transvaalbuurt gemeente Amsterdam, onderdeel van de stad Amsterdam in de Nederlandse provincie Noord-Holland. De buurt ligt tussen de Wijk van Amsterdam Transvaalkade in het zuiden, de Wibautstraat in het westen, de spoorlijn tussen Amstelstation en Muiderpoortstation in het noorden en de Linnaeusstraat in het oosten. De buurt heeft een oppervlakte van 38 hectare, telt 4500 woningen en heeft bijna 10.000 inwoners.[1] Inhoud Kerngegevens 1 Oorsprong Gemeente Amsterdam 2 Naam Stadsdeel Oost 3 Statistiek Oppervlakte 38 ha 4 Bronnen Inwoners 10.000 5 Noten Oorsprong De Transvaalbuurt is in de jaren '10 en '20 van de 20e eeuw gebouwd als stadsuitbreidingswijk. Architect Berlage ontwierp het stratenplan: kromme en rechte straten afgewisseld met pleinen en plantsoenen. Veel van de arbeiderswoningen werden gebouwd in de stijl van de Amsterdamse School. Dit maakt dat dat deel van de buurt een eigen waarde heeft, met bijzondere hoekjes en mooie afwerkingen. Nadeel van deze bouw is dat een groot deel van de woningen relatief klein is. Aan de basis van de Transvaalbuurt stonden enkele woningbouwverenigingen, die er huizenblokken -

Uitvoeringsprogramma Aanpak Binnenstad Onderscheidt 6 Prioriteiten Die Samen En in Wisselwerking Met Elkaar Bijdragen Aan De Opgaven in De Binnenstad

AANPAK BINNENSTAD Uitvoeringsprogramma december 2020 i. Inhoud 1. Vooraf 3 Van ambitie naar maatregelen 4 2. Aanleiding 5 3. Ambitie 6 4. Uitvoeringsprogramma 7 5. Opgaven 9 BINNENSTAD AANPAK Enkele voorbeelden van Aanpak Binnenstad 10 2 6. Maatregelen 11 6.1 Functiemenging en diversiteit 12 6.2 Beheer en handhaving 16 6.3 Een waardevolle bezoekerseconomie 20 6.4 Versterken van de culturele verscheidenheid en buurtidentiteiten 23 6.5 Bevorderen van meer en divers woningaanbod 26 6.6 Meer verblijfsruimte en groen in de openbare ruimte 29 7. Organisatie en financiën 32 8. Samenwerking en voortgang 33 UITVOERINGSPROGRAMMA 1. Vooraf In mei 2020 is in een raadsbrief de Aanpak Binnenstad gelanceerd. Deze aanpak combineert maatregelen en visie voor zowel de korte als langere termijn, formuleert de opgaven in de binnenstad breed en in samenhang, maar stelt tegelijkertijd ook prioriteiten. Deze aanpak bouwt voort op dat wat is ingezet door de gemeente en tal van anderen rond de binnenstad, maar maakt waar nodig ook scherpe keuzes. En deze aanpak pakt problemen aan én biedt perspectief. Wat ons treft in de vele gesprekken die Een deel van deze maatregelen is reeds De kracht van een set maatregelen is dat wij in de afgelopen maanden gevoerd in gang gezet, want we beginnen niet bij ze goed te adresseren en concreet zijn. hebben met bewoners, ondernemers, nul. Andere maatregelen nemen wij in De kwetsbaarheid is dat ze een zekere vastgoedeigenaren en culturele onderzoek of voorbereiding en met weer mate van uitwisselbaarheid suggereren. instellingen, is dat er een breed gedragen andere starten wij in het kader van dit Dat laatste willen wij weerleggen. -

A B N N N Z Z Z C D E F G H I J K

A8 COENTUNNELWEG W WEG ZIJKANAAL G AMMERGOU G R O 0 T E Gemeente Zaanstad D N M E E R Gemeente Oostzaan K L E I N E AA V A N B BOZEN M E E R NOORDER BOS LANDSMEER E EKSTRAA SYMON SPIERSWEG V E E R MEERTJE T ZUIDEINDE AFRIKAHAVEN NOORDER-IJPLAS NOOR : BAARTHAVEN D ZEE ISAAC KAN Broekermeerpolder NOORDERWEG AAL ( IN AANLEG ) K N O O P P U N T ZUIDEINDE DORS MACHINEWEG RUIGOORD ZAANDAM C O E N P L E I N WIM ARKEN AE THOMASSENHAVEN HET SCHOUW Volgermeer- Gemeente Waterland SPORTPARK R M EER EN W E G BR OEKE Belmermeerpolder RINGWEG-NOO MIDD Hemspoortunnel OOSTZANER- polder Houtrak- WERF DIRK KADOELENWEG polder R D Gemeente Landsmeer RIJPERWEG METSELAARHAVEN A 1 0 SWEG AMERIKAHAVEN R OOSTZANERWERF H e m p o n t ENAA STELLINGWEG MOL S T R A A T SPORTPARK STEN T OR MELKWEG UITDAM O O TW B EG ANKERWEG W E G RUIJGOORDWEG WESTHAVENWEG STOOM KADOELEN BROEKERGOUW TER A M D M Burkmeer- ER STELLINGWEG UIT D IE ELBAWEG C A R L R E AVEN SLOCH Veenderij H Windturbine IJNI HORNWEG ERSH polder V o e t v e e r CACAO AVEN KADO SPORTPARK Grote Blauwe Polder KOMETENSINGEL Sportpark Zunderdorp E R R.I. Groote OT DIE LANDS ELENWEG TUINDORP KADOELEN LATEXWEG IJpolder METEORENWEG Tuindorp AAL SL NOORDERBREEDTE N WESTHAVEN OOSTZAAN KA COENTUNNEL CORNELIS DOUWESWEG Oostzaan MIDDENWEG MEERDER JAN VAN RIEBEECK G O U W HOLY KOFFIEWEG RUIGOORD MIDDENWEG RUIGOORD PETROLEUM HOLLANDSCH HOLYSLOOT DIJK NDAMMER HAVEN NOORD E : INCX POPP AUSTRALIEHA V E N ZIJKANAAL I POMONASTRAAT NWEG HORNWEG WESTERLENGTE RWEG OCEANE USSEL A N A N A S HAVEN NIEUWE HEMWEG P L E I N BUIKSLOOT RDE R.I. -

Station Amsterdam Hispeed Amsterdam Zuid of Amsterdam Centraal Als Aanlandingsplaats Voor De HST ?

Station Amsterdam Hispeed Amsterdam Zuid of Amsterdam Centraal als aanlandingsplaats voor de HST ? John Baggen en Mig de Jong Stelling: Amsterdam Centraal is voor de middellange termijn het meest geschikte station voor hogesnelheids- treinen in Amsterdam Amsterdam Zuid biedt op lange termijn, na voltooiing van de Zuidas, een betrouwbaarder hogesnelheidstreindienst [email protected] [email protected] Technische Universiteit Delft Paper voor de Plandag 2010 1 Inleiding Amsterdam is in de afgelopen jaren vertrek- en aankomstpunt geworden van een reeks hogesnelheids- treinen waaronder Thalys, ICE International en de nationale Fyra. Met de verdere ingebruikname van de HSL-Zuid zal het netwerk in de nabije toekomst verder uitgebreid worden. NS Hispeed (voorheen NS Internationaal) zet genoemde treinen in de markt, samen met de IC Brussel en de IC Berlijn. Historisch gezien is het Amsterdamse internationale vertrek- en aankomststation altijd Amsterdam Centraal geweest. Ook nu is Amsterdam Centraal nog het brandpunt van het internationale treinver- keer. Alleen de IC Berlijn is enkele jaren geleden verplaatst naar de stations Amsterdam Zuid en Schiphol. Het door Cuypers ontworpen laat-19e-eeuwse stationsgebouw is een representatief decor voor deze prestigieuze treinverbindingen. Eind januari zijn plannen gepresenteerd voor een omvangrijke renova- tie en modernisering van het Stationseiland Amsterdam Centraal waar ook al aan de Noord-Zuidlijn en een nieuw busstation gewerkt wordt. Een dag later werden echter de nieuwe plannen voor de Zuid- -

Een Tijdlijn Van Stedelijke Vernieuwing

EEN TIJDLIJN VAN STEDELIJKE VERNIEUWING 1948/1968 CENTRALE OVERHEID, PLANMATIG, AANBODGESTUURD 1968/1988 CENTRALE OVERHEID, PROCESMATIG, VRAAGGESTUURD 1988/2008 MARKTPARTIJEN, PLANMATIG, AANBODGESTUURD 2008/2028 MARKTPARTIJEN & BURGERS, DYNAMISCH, VRAAGGESTUURD van industrie naar kenniseconomie nieuw accent op kwaliteit en stedelijke economie neoliberalisme wederopbouw en woningnood intrede marktpartijen en verzelfstandiging corporaties planmatig bouwen tuinsteden centrale overheid VINEX aanbodgestuurde markt IJ oevers, haveneilanden, Zuid as planmatige aanpak binnenstad gentrification binnenstad cityvorming verkeersdoorbraken neerwaartse spiraal tuinsteden krot opruiming nieuwe vernieuwingsopgave kantorenbouw masterplan marktpartijen ???? politiek tijdens hoogconjunctuur gentrificering tuinsteden?? gentrification = sociale toenemende schaalvergroting vernieuwing 1948/1968 1968/1988 1988/2008 2008/2028 2028/en verder de binnenstad in crisis de vastgoedcrisis toenemend verzet stagnerende woningmarkt opkomst sociale bewegingen lege kantoren aanzet stadsvernieuwing stkterk afdfnemende uitvinden bouwen in de context investeringscapaciteit straat als publiek domein nieuwe corporatie Lieven de Key nieuwe investeerders en ruimte voor burgerinitiatief vraaggestuurd planproces (de)centrale overheid "open planproces" bouwen voor de buurt kanaliseren ambities in gebiedsontwikkeling crisis, bezuinigingen verschraling architectt & modellen voor dynamiek stedenbw WEDEROPBOUW 1948/1968 De uitgaven voor volkshuisvesting worden centraal gestuurd. Het aanbod