PF Vol. 07 No. 02.Pdf (10.14Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A C C E P T E

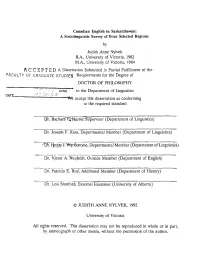

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

A Finding Aid to the Emigration And

A Finding Aid to the Emigration and Immigration Pamphlets Shortt JV 7225 .E53 prepared by Glen Makahonu k Shortt Emigration and Immi gration Pamphlets JV 7225 .E53 This collection contains a wide variety of materials on the emigration and immigration issue in Canada, especially during the period of the early 20th century. Two significant groupings of material are: (1) The East Indians in Canada, which are numbered 24 through 50; and (2) The Fellowship of the Maple Leaf, which are numbered 66 through 76. 1. Atlantica and Iceland Review. The Icelandic Settlement in Cdnada. 1875-1975. 2. Discours prononce le 25 Juin 1883, par M. Le cur6 Labelle sur La Mission de la Race Canadienne-Francaise en Canada. Montreal, 1883. 3. Immigration to the Canadian Prairies 1870-1914. Ottawa: Information Canada, 19n. 4. "The Problem of Race", The Democratic Way. Vol. 1, No. 6. March 1944. Ottawa: Progressive Printers, 1944. 5. Openings for Capital. Western Canada Offers Most Profitable Field for Investment of Large or Small Sums. Winnipeg: Industria1 Bureau. n.d. 6. A.S. Whiteley, "The Peopling of the Prairie Provinces of Canada" The American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 38, No. 2. Sept. 1932. 7. Notes on the Canadian Family Tree. Ottawa: Dept. of Citizenship and Immigration. 1960. 8. Lawrence and LaVerna Kl ippenstein , Mennonites in Manitoba Thei r Background and Early Settlement. Winnipeg, 1976. 9. M.P. Riley and J.R. Stewart, "The Hutterites: South Dakota's Communal Farmers", Bulletin 530. Feb. 1966. 10. H.P. Musson, "A Tenderfoot in Canada" The Wide World Magazine Feb. 1927. 11. -

A Thesis for the Degree of University of Regina Regina, Saskatchewan

Hitched to the Plow: The Place of Western Pioneer Women in Innisian Staple Theory A Thesis Subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology University of Regina by Sandxa Lynn Rollings-Magnusson Regina, Saskatchewan June, 1997 Copyright 1997: S.L. Rollings-Magnusson 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de micro fi ch el^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemîse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Romantic images of the opening of the 'last best west' bring forth visions of hearty pioneer men and women with children in hand gazing across bountiful fields of golden wheat that would make them wealthy in a land full of promise and freedom. The reality, of course, did not match the fantasy. -

A Acquisition, 314 Action-Oriented Approach, 221 Additional Language

Index A B Acquisition, 314 Balassi Institute, 381 Action-oriented approach, 221 Bantu education, 449 Additional language curriculum development, Bethlen Gábor Hungarian Language School, 106 386 Adult heritage speaker grammars, 193 Bilingual cognitive science research, 196 African diaspora, 597 Bilingual education, 117, 448, 733 African heritage languages, 447 heritage language skills, 777 African immigrants, 596, 598, 601, 602, 604 language and culture revitalization, 781 Afrikaans, 450 systemic discrimination, 779–780 Aggressive policy, 695 transitional bilingualism vs. two-way Albanian heritage language bilingualism, 778 Greek teachers’ attitudes and practices, Bilingualism, 156, 264, 265, 287, 290, 292, 530–531 299, 438, 542, 544, 545, 557, 674 immigrant background children’s language, Bilingual minority education, 545–546 530–531 Bilinguals, 603 immigrant parents’attitudes and practices, Bilingual students, in monolingual school 531–533 system, 118–120 Ali Levent, 484 Biographical study, Chinese origin. See Chinese Amazonian languages, 794 origin, Spain American Community Survey, 736 Bora language, 19 American Council of Teachers of Foreign Amazonian languages, 794 Languages (ACTFL), 368 language policies in Peru, 796–797 American Sign Language (ASL), 755, 757, 758, Spanish influence, 793–794 761, 763 and workshops, 789–790 Ampiyacu river communities, 790 Brain drain, 705 Anglonormativity, 456, 460 British Sign Language (BSL), 756, 758 Arabic, 448 Bureaucratization of alphabet, 795 Arany János Hungarian Week-end School, 388 Asian heritage languages, 448 C Australian Curriculum, 467, 470, 472 Calvin Hungarian Educational Association, 387 Australian Tertiary Entrance Rank (ATAR) Cambridge, Italian community in, 704 score, 437 Canada, SHL. See Spanish heritage language Authentic disciplinary practices, 54, 65 (SHL) Autonomous learning, Chinese HL learners. -

Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing

UNIVERSITY PRESS <http://www.thepress.purdue.edu> CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb> Purdue University Press ©Purdue University The Library Series of the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access quarterly in the humanities and the social sciences CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture publishes scholarship in the humanities and social sciences following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the CLCWeb Library Series are 1) articles, 2) books, 3) bibliographies, 4) resources, and 5) documents. Contact: <[email protected]> Selected Bibliography of Work on Canadian Ethnic Minority Writing <http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweblibrary/canadianethnicbibliography> Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, Asma Sayed, and Domenic A. Beneventi 1) literary histories and bibliographies of canadian ethnic minority writing 2) work on canadian ethnic minority writing This selected bibliography is compiled according to the following criteria: 1) Only English- and French-language works are included; however, it should be noted that there exists a substantial corpus of studies in a number Canada's ethnic minority languages; 2) Critical works about the literatures of Canada's First Nations are not included following the frequently expressed opinion that Canadian First Nations literatures should not be categorized within Canadian "Ethnic" writing but as a separate corpus; 3) Literary criticism as well as theoretical texts are included; 4) Critical texts on works of authors writing in English and French but usually viewed or which could be considered as "Ethnic" authors (i.e., immigré[e]/exile individuals whose works contain Canadian "Ethnic" perspectives) are included; 5) Some works dealing with US or Anglophone-American Ethnic Minority Writing with Canadian perspectives are included; 6) M.A. -

Hungarian Studies ^Eviezv Vol

Hungarian Studies ^eviezv Vol. XXV, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 1998) Special Volume: Canadian Studies on Hungarians: A Bibliography (Third Supplement) Janos Miska, comp. This special volume contains a bibliography of recent (1995-1998) Canadian publications on Hungary and Hungarians in Canada and else- where. It also offers a guide to archival sources on Hungarian Canadians in Hungary and Canada; a list of Hungarian-Canadian newspapers, jour- nals and other periodicals ever published; as well as biographies of promi- nent Hungarian-Canadian authors, educators, artists, scientists and com- munity leaders. The volume is completed by a detailed index. The Hungarian Studies Review is a semi- annual interdisciplinary journal devoted to the EDITORS publication of articles and book reviews relat- ing to Hungary and Hungarians. The Review George Bisztray is a forum for the scholarly discussion and University of Toronto analysis of issues in Hungarian history, politics and cultural affairs. It is co-published by the N.F. Dreisziger Hungarian Studies Association of Canada and Royal Military College the National Sz£ch6nyi Library of Hungary. Institutional subscriptions to the HSR are EDITORIAL ADVISERS $12.00 per annum. Membership fees in the Hungarian Studies Association of Canada in- Oliver Botar clude a subscription to the journal. University of Manitoba For more information, visit our web-page: Geza Jeszenszky http://www.ccsp.sfu.ca/calj.hsr Budapest- Washington Correspondence should be addressed to: Ilona Kovacs National Szechenyi Library The Editors, Hungarian Studies Review, University of Toronto, Mlria H. Krisztinkovich 21 Sussex Ave., Vancouver Toronto, Ont., Canada M5S 1A1 Barnabas A. Racz Statements and opinions expressed in the HSR Eastern Michigan U. -

Impact of Acculturation on Socialization Beliefs and Behavioral Occurences Among Indo-Canadian Immigrants

Impact of Acculturation On Socialization Beliefs and Behavioral Occurences Among Indo-Canadian Immigrants ZEYNEP AYCAN * and RABINDRA N. KANUNGO ** INTRODUCTION The multicultural character of the Canada has emerged as a result of the society hosting immigrants belonging to various ethno-cultural groups. When the immigrants enter Canada, they bring with them a cultural baggage that contains a unique set of values, attitudes, socialization beliefs and behavioral norms required within the country of origin. However, as they settle in Canada, their constant interaction with the host society gradually brings about changes in these values, attitudes, beliefs, and behavioral norms. This process of transformation is known as the process of accultiuation (Redfield, Linton, &°Herskovits, 1938). Harmonious growth and maintenance of the Canadian society depends on the development of appropriate acculturation attitudes, and related socialization beliefs and practices of the various ethno-cultural immigrant groups. This study ex£imines the experience of Indo-Canadian parents and their children by identifying their acculturation attitudes, and the ways in which such attitudes are related to socialization beliefs and behaviour occurrences. The Acculturation Framework The model of acculturation attitudes proposed by Berry (1984) raises two critical questions: (a) whether or not an acculturating individual values maintaining his/her own cultural identity and characteristics, and (b) whether or not maintaining relationships with the larger society is considered to be of value to an acculturating individual (Berry, Poortinga, Segall,&Dasen, 1992). Depending on the answers to these questions, four possible altemative attitudes can be identified (Figure 1). First, the attitude of "assimilation," occurs when an acculturating individual does not wish to maintain his/her ethnic identity, but seeks relations with the larger society. -

“Art Is in Our Heart”

“ART IS IN OUR HEART”: TRANSNATIONAL COMPLEXITIES OF ART PROJECTS AND NEOLIBERAL GOVERNMENTALITY _____________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _____________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________ By G.I Tinna Grétarsdóttir January, 2010 Examining Committee Members: Dr. Jay Ruby, Advisory Chair, Anthropology Dr. Raquel Romberg, Anthropology Dr. Paul Garrett, Anthropology Dr. Roderick Coover, External Member, Film and Media Arts, Temple University. i © Copyright 2010 by G.I Tinna Grétarsdóttir All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT “ART IS IN OUR HEART”: TRANSNATIONAL COMPLEXITIES OF ART PROJECTS AND NEOLIBERAL GOVERNMENTALITY By G.I Tinna Grétarsdóttir Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, January 2010 Doctoral Advisory Committee Chair: Dr. Jay Ruby In this dissertation I argue that art projects are sites of interconnected social spaces where the work of transnational practices, neoliberal politics and identity construction take place. At the same time, art projects are “nodal points” that provide entry and linkages between communities across the Atlantic. In this study, based on multi-sited ethnographic fieldwork in Canada and Iceland, I explore this argument by examining ethnic networking between Icelandic-Canadians and the Icelandic state, which adopted neoliberal economic policies between 1991 and 2008. The neoliberal restructuring in Iceland was manifested in the implementation of programs of privatization and deregulation. The tidal wave of free trade, market rationality and expansions across national borders required re-imagined, nationalized accounts of Icelandic identity and society and reconfigurations of the margins of the Icelandic state. Through programs and a range of technologies, discourses, and practices, the Icelandic state worked to create enterprising, empowered, and creative subjects appropriate to the neoliberal project. -

Canadian Studies: the Hungarian Contribution

Ad Americam. Journal of American Studies 21 (2020): ISSN: 1896-9461, https://doi.org/10.12797/AdAmericam.21.2020.21.06 Licensing information: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 János Kenyeres Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0294-9714 Canadian Studies: The Hungarian Contribution Canadian Studies was launched in Hungary in 1979, when the first course in Canadian literature was offered at the English Department of Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest. This article is intended to explore the history of this discipline in the past 40+ years, fo- cusing on the growing awareness of Canada and its culture in Hungarian academic and intellectual life. As early as the mid-1980s, universities in Hungary offered various cours- es in Canadian Studies, which were followed by a large number of publications, con- ferences, and the institutionalization of the field. The article gives a survey of Canadian Studies in Hungary in the international context, showing the ways in which interaction with colleagues in Europe and beyond, and with institutions, such as the Central Euro- pean Association for Canadian Studies, has promoted the work of Hungarian researchers. The article also discusses the fields of interest and individual achievements of Hungarian scholars, as well as the challenges Canadian Studies has faced. Key words: Canadian Studies; Hungary; university; scholarship; research; history The study of Canada by Hungarians is usually considered a recent development compared to academic research on the history and culture of other nations. Howev- er, evidence shows that, in a sense, the history of contacts between the two countries goes back several centuries. -

Unsettling the White Noise: Deconstructing the Nation-Building

Unsettling the White Noise: Deconstructing the Nation-Building Project of CBC Radio One’s Canada Reads By Emily M. Burns A thesis submitted to the Graduate Program in the Department of Gender Studies in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada August, 2012 Copyright @ Emily M. Burns, 2012 Abstract The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Canada Reads program, based on the popular television show Survivor, welcomes five Canadian personalities to defend one Canadian book, per year, that they believe all Canadians should read. The program signifies a common discourse in Canada as a nation-state regarding its own lack of coherent and fixed identity, and can be understood as a nationalist project. I am working with Canada Reads as an existing archive, utilizing materials as both individual and interconnected entities in a larger and ongoing process of cultural production – and it is important to note that it is impossible to separate cultural production from cultural consumption. Each year offers a different set of insights that can be consumed in their own right, which is why this project is written in the present tense. Focusing on the first ten years of the Canada Reads competition, I argue that Canada Reads plays a specific and calculated role in the CBC’s goal of nation-building: one that obfuscates repressive national histories and legacies and instead promotes the transformative powers of literacy as that which can conquer historical and contemporary inequalities of all types. This research lays bare the imagined and idealized ‘communities’ of Canada Reads audiences that the CBC wishes to reflect in its programming, and complicates this construction as one that abdicates contemporary responsibilities of settlers. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

PF Vol6 No1.Pdf (9.908Mb)

PRAIRIE FORUM VoI.6,No.1 Spring 1981 CONTENTS F.W.G. Haultain, Territorial Politics and the Quasi-party System Sta"nley Gordon The WCTU on the Prairies, 1886-1930: An Alberta-Saskatchewan Comparison 17 Nancy M. Sheehan Soldier Settlement and Depression Settlement in the Forest 35 Fringe of Saskatchewan John McDonald The Conservative Party of Alberta under Lougheed, 1965-71: Building an Image and an Organization 57 Meir Serfaty The Historiography of the Red River Settlement, 1830-1868 75 Frits Pannekoek Prairie Theses, 1978-79 87 Book Reviews (see overleaf) 101 PRAIRIE FORUM is published twice yearly, in Spring and Fall,at an annual subscription of $15.00. All subscriptions, correspondence and contribu tions should be sent to The Editor, Prairie Forum, Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina, Regina,Saskatchewan, Canada, S4S OA2. Subscribers will also receive the Canadian Plains Bulletin, the newsletter of the Canadian Plains Research Center. PRAIRIE FORUM is not responsible for statements, either of fact or of opinion, made by contributors. COPYRIGHT1981 ISSN0317-6282 CANADIAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER BOOK REVIEWS paNTING, J.R. and GIBBINS, R., Out of Irrelevance 101 by D. Bruce Sealey KROTZ, lARRY, Urban Indians: The Strangers in Canada's Cities 102 by Oliver Brass KROETSCH, ROBERT, ed., Sundogs: Stories from Saskatchewan 104 by Donald C. Kerr DURIEUX, MARCEL, Ordinary Heroes: The Journal of a French Pioneer in Alberta by Andre Lalonde 106 BOCKING, D.H., ed., Pages from the Past: Essays on Saskatchewan , History by Elizabeth Blight 107 OWRAM, DOUG, Promise of Eden: The Canadian Expansionist Movement and the Idea of the West, 1856-1900 110 by Donald Swainson KOESTER, C.B., Mr.