PF Vol6 No1.Pdf (9.908Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A C C E P T E

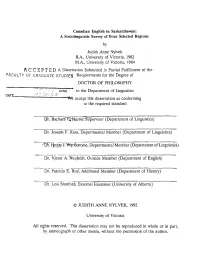

Canadian English in Saskatchewan: A Sociolinguistic Survey of Four Selected Regions by Judith Anne Nylvek B.A., University of Victoria, 1982 M.A., University of Victoria, 1984 ACCEPTE.D A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .>,« 1,^ , I . I l » ' / DEAN in the Department of Linguistics o ate y " /-''-' A > ' We accept this dissertation as conforming to the required standard Xjx. BarbarSTj|JlA^-fiVSu^rvisor (Department of Linguistics) Dr. Joseph F. Kess, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) CD t. Herijy J, WgrKentyne, Departmental Member (Department of Linguistics) _________________________ Dr. Victor A. 'fiJeufeldt, Outside Member (Department of English) _____________________________________________ Dr. Pajtricia E. Ro/, Additional Member (Department of History) Dr. Lois Stanford, External Examiner (University of Alberta) © JUDITH ANNE NYLVEK, 1992 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or other means, without the permission of the author. Supervisor: Dr. Barbara P. Harris ABSTRACT The objective of this study is to provide detailed information regarding Canadian English as it is spoken by English-speaking Canadians who were born and raised in Saskatchewan and who still reside in this province. A data base has also been established which will allow real time comparison in future studies. Linguistic variables studied include the pronunciation of several individual lexical items, the use of lexical variants, and some aspects of phonological variation. Social variables deemed important include age, sex, urbanlrural, generation in Saskatchewan, education, ethnicity, and multilingualism. The study was carried out using statistical methodology which provided the framework for confirmation of previous findings and exploration of unknown relationships. -

A Finding Aid to the Emigration And

A Finding Aid to the Emigration and Immigration Pamphlets Shortt JV 7225 .E53 prepared by Glen Makahonu k Shortt Emigration and Immi gration Pamphlets JV 7225 .E53 This collection contains a wide variety of materials on the emigration and immigration issue in Canada, especially during the period of the early 20th century. Two significant groupings of material are: (1) The East Indians in Canada, which are numbered 24 through 50; and (2) The Fellowship of the Maple Leaf, which are numbered 66 through 76. 1. Atlantica and Iceland Review. The Icelandic Settlement in Cdnada. 1875-1975. 2. Discours prononce le 25 Juin 1883, par M. Le cur6 Labelle sur La Mission de la Race Canadienne-Francaise en Canada. Montreal, 1883. 3. Immigration to the Canadian Prairies 1870-1914. Ottawa: Information Canada, 19n. 4. "The Problem of Race", The Democratic Way. Vol. 1, No. 6. March 1944. Ottawa: Progressive Printers, 1944. 5. Openings for Capital. Western Canada Offers Most Profitable Field for Investment of Large or Small Sums. Winnipeg: Industria1 Bureau. n.d. 6. A.S. Whiteley, "The Peopling of the Prairie Provinces of Canada" The American Journal of Sociology. Vol. 38, No. 2. Sept. 1932. 7. Notes on the Canadian Family Tree. Ottawa: Dept. of Citizenship and Immigration. 1960. 8. Lawrence and LaVerna Kl ippenstein , Mennonites in Manitoba Thei r Background and Early Settlement. Winnipeg, 1976. 9. M.P. Riley and J.R. Stewart, "The Hutterites: South Dakota's Communal Farmers", Bulletin 530. Feb. 1966. 10. H.P. Musson, "A Tenderfoot in Canada" The Wide World Magazine Feb. 1927. 11. -

Grade 12 Canadian History: a Postcolonial Analysis. A

GRADE 12 CANADIAN HISTORY: A POSTCOLONIAL ANALYSIS. A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the Degree ofMasters ofEducation in the Department ofEducational Foundations University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon by T. Scott Farmer Spring 2004 © Copyright T. Scott Farmer, 2004. All Rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying ofthis thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made ofany material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head ofthe Department ofEducational Foundations University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N OXl ABSTRACT The History 30: Canadian Studies Curriculum Guide and the History 30: Canadian Studies A Teacher's Activity Guide provide teachers ofgrade twelve Canadian history direction and instruction. -

From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View Versus the Narrow View

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-09-30 From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View versus the Narrow View Kuiken, Jacob Kuiken, J. (2014). From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View versus the Narrow View (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/26237 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1885 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY From Social Welfare to Social Work, the Broad View versus the Narrow View by Jacob Kuiken A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN SOCIAL WORK CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2014 © JACOB KUIKEN 2014 Abstract This dissertation looks back through the lens of a conflict that emerged during the development of social work education in Alberta, and captured by a dispute about the name of the school. The difference of a single word – welfare versus work – led through selected events in the history of social work where similar differences led to disputes about important matters. The themes of the dispute are embedded in the Western Tradition with the emergence of social work and its development at the focal point for addressing the consequences described as a ‘painful disorientation generated at the intersections where cultural values clash.’ In early 1966, the University of Calgary was selected as the site for Alberta’s graduate level social work program following a grant and volunteers from the Calgary Junior League. -

A Thesis for the Degree of University of Regina Regina, Saskatchewan

Hitched to the Plow: The Place of Western Pioneer Women in Innisian Staple Theory A Thesis Subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Sociology University of Regina by Sandxa Lynn Rollings-Magnusson Regina, Saskatchewan June, 1997 Copyright 1997: S.L. Rollings-Magnusson 395 Wellington Street 395, nie Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pemettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de micro fi ch el^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othemîse de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Romantic images of the opening of the 'last best west' bring forth visions of hearty pioneer men and women with children in hand gazing across bountiful fields of golden wheat that would make them wealthy in a land full of promise and freedom. The reality, of course, did not match the fantasy. -

Allan A.Warrak

1 ALLAN A. WARRAK Allan Alexander Warrack was born on May 24, 1937 in Calgary, Alberta and was raised in Langdon, southeast of the city. He attended Olds Agricultural College before going on to the University of Alberta where he received a B Sc degree in agricultural sciences in 1961. He then attended Iowa State University where he obtained MS and PhD degrees in 1963 and 1967, respectively. He began teaching at the University of Alberta and, in 1971, ran for provincial office in the riding of Three Hills. He defeated the Social Credit incumbent by eight votes and was part of the victory that brought the Progressive Conservative party to power ending 36 years of Social Credit rule. The new Premier, Peter Lougheed, appointed him to the Executive Council of Alberta and Minister of Lands and Forests. Warrack ran for a second term in office, in 1975, and readily defeated three other candidates, and was appointed Minister of Utilities and Telephones. Warrack retired from provincial politics at dissolution of the Legislative Assembly in 1979. He returned to the University of Alberta where he initially taught agricultural economics and later business economics in the Faculty of Business. He moved up the academic ranks and became a tenured professor as well as serving for five years as University of Alberta Vice-President Administration and Finance. Warrack also served as Associate Dean of the Master of Public Management Program. He is the recipient of a number of awards including the Province of Alberta Centennial Medal (2005) and the University of Alberta Alumni Honour Award (2009). -

INDEMNITIES and ALLOWANCES 59 10.—By-Elections from the Date

INDEMNITIES AND ALLOWANCES 59 10.—By-elections from the Date of the General Election, June 27,1949, to Mar. SI, 1952 Votes Province Date Voters Polled Total Name Party and of on by Votes of New P.O. Affili Electoral District By-election List Mem Polled Member Address ation ber No. No. No. Prince Edward Island- Queens June 25, 1951 25,230 9,540 18,733 J. A. MACLEAN. Beaton's Mills P.C. No?a Scotia- Annapolis-Kings .... June 19, 1950 31,158 14,255 26,065 G. C. NOWLAN. .. Wolfville. P.C. Halifax June 19, 1950 90,913 24,665 43,431 S. R. BALCOM. ... Halifax... Lib. New Brunswick— Restigouche- Madawaska Oct. 24, 1949 33,571 10,124 17,516 P. L. DUBB Edmundston. Lib. Quebec— Gatineau Oct. 24, 1949 19,919 5,438 9,340 J. C. NADON Maniwaki Lib. Kamouraska Oct. 24, 1949 17,845 6,033 11,365 A. MASSE Kamouraska.. Lib. Island of Montreal and lie Jesus— Jacques-Cartier Oct. 24, 1949 35,710 9,327 16,366 E. LEDTJC Lachine Lib. Laurier Oct. 24, 1949 35,933 10,164 11,113 J. E. LEFRANCOIS Montreal Lib. Mercier Oct. 24, 1949 41,584 9,389 12,658 M. MONETTE. Pointe - aux - Trembles Lib. Cartier June 19, 1950 34,549 9,701 18,220 L. D. CRESTOHL. Outremont... Lib. St. Mary Oct. 16, 1950 34,167 9,579 15,694 H. DUPUIS Montreal Ind. L. Joliette-L'Assomp- tion-Montcalm... Oct. 3, 1950 Acclamation M. BRETON Joliette Lib. Rimouski Oct. 16, 1950 29,844 9,976 20,685 J. -

PRISM::Advent3b2 8.25

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 39th PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION 39e LÉGISLATURE, 1re SESSION Journals Journaux No. 1 No 1 Monday, April 3, 2006 Le lundi 3 avril 2006 11:00 a.m. 11 heures Today being the first day of the meeting of the First Session of Le Parlement se réunit aujourd'hui pour la première fois de la the 39th Parliament for the dispatch of business, Ms. Audrey première session de la 39e législature, pour l'expédition des O'Brien, Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. Marc Bosc, Deputy affaires. Mme Audrey O'Brien, greffière de la Chambre des Clerk of the House of Commons, Mr. R. R. Walsh, Law Clerk and communes, M. Marc Bosc, sous-greffier de la Chambre des Parliamentary Counsel of the House of Commons, and Ms. Marie- communes, M. R. R. Walsh, légiste et conseiller parlementaire de Andrée Lajoie, Clerk Assistant of the House of Commons, la Chambre des communes, et Mme Marie-Andrée Lajoie, greffier Commissioners appointed per dedimus potestatem for the adjoint de la Chambre des communes, commissaires nommés en purpose of administering the oath to Members of the House of vertu d'une ordonnance, dedimus potestatem, pour faire prêter Commons, attending according to their duty, Ms. Audrey O'Brien serment aux députés de la Chambre des communes, sont présents laid upon the Table a list of the Members returned to serve in this dans l'exercice de leurs fonctions. Mme Audrey O'Brien dépose sur Parliament received by her as Clerk of the House of Commons le Bureau la liste des députés qui ont été proclamés élus au from and certified under the hand of Mr. -

Federal Members of the House of Commons for The

FEDERAL MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS FOR THE NORTH–WEST TERRITORIES Adamson, Alan Joseph 1857–1928 Humboldt ................................................................................................................. 1904 – 1908 Lib Cash, Edward L. 1849 – 1922 Mackenzie ............................................................................................................... 1904 – 1908 Lib Davin, Nicholas Flood 1843 – 1901 Assiniboia West ....................................................................................................... 1887 – 1900 Cons Davis, Donald Watson 1849 – 1906 Alberta ..................................................................................................................... 1887 – 1896 Cons Davis, Thomas Osborne 1856 – 1917 Saskatchewan ......................................................................................................... 1896 – 1904 Lib Dewdney, Edgar 1835 – 1916 Assiniboia East ........................................................................................................ 1888 – 1892 Cons Douglas, James Moffat 1839 – 1920 Assiniboia East ........................................................................................................ 1896 – 1904 Ind Lib Herron, John 1853 – 1936 Alberta ..................................................................................................................... 1904 – 1908 Cons Lake, Richard Stuart 1860 – 1950 Qu’Appelle .............................................................................................................. -

The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns

Choice or Consensus?: The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns Jared J. Wesley PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Calgary Paper for Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan May 30, 2007 Comments welcome. Please do not cite without permission. CHOICE OR CONSENSUS?: THE 2006 FEDERAL LIBERAL AND ALBERTA CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGNS INTRODUCTION Two of Canada’s most prominent political dynasties experienced power-shifts on the same weekend in December 2006. The Liberal Party of Canada and the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta undertook leadership campaigns, which, while different in context, process and substance, produced remarkably similar outcomes. In both instances, so-called ‘dark-horse’ candidates emerged victorious, with Stéphane Dion and Ed Stelmach defeating frontrunners like Michael Ignatieff, Bob Rae, Jim Dinning, and Ted Morton. During the campaigns and since, Dion and Stelmach have been labeled as less charismatic than either their predecessors or their opponents, and both of the new leaders have drawn skepticism for their ability to win the next general election.1 This pair of surprising results raises interesting questions about the nature of leadership selection in Canada. Considering that each race was run in an entirely different context, and under an entirely different set of rules, which common factors may have contributed to the similar outcomes? The following study offers a partial answer. In analyzing the platforms of the major contenders in each campaign, the analysis suggests that candidates’ strategies played a significant role in determining the results. Whereas leading contenders opted to pursue direct confrontation over specific policy issues, Dion and Stelmach appeared to benefit by avoiding such conflict. -

Gail Simpson

Ch F-X ang PD e 1 w Click to buy NOW! w m o w c .d k. ocu-trac GAIL SIMPSON Date and place of birth (if available): Edmonton, Alberta Date and place of interview: June 27th, 2013; Gail’s home in Calgary, NW Name of interviewer: Peter McKenzie-Brown Name of videographer: Full names (spelled out) of all others present: Consent form signed: Yes Transcript reviewed by subject: Interview Duration: 53 minutes Initials of Interviewer: PMB Last name of subject: SIMPSON PMB: I’m now interviewing Gail Simpson. We’re at her house in North Western Calgary. This is one of the days of the catastrophe in which the river flooded and much of the city has really been washed away. It’s been an awful catastrophe for many people. The date is the 27th of June 2013. So, Gail, thank you very much for agreeing to participate in this. I wonder whether you could begin by just telling us about your career, especially in respect to the oil sands, because I know you’ve had a very diverse career since you left. SIMPSON: Yes, well I would be happy to Peter. Thank you. PMB: Including where you were born, when you were born and where you went to school and so on? SIMPSON: Okay. Well, I was born in Edmonton, Alberta and haven’t strayed too much further away than that. I lived in Edmonton for about 30 years I guess, before I moved down to Calgary. I relocated here in 1997. So, I grew up in central Alberta and I went back to Edmonton after high school to take some further training and education. -

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY of ALBERTA [The House Met at 2:30

December 8, 1981 ALBERTA HANSARD 2177 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF ALBERTA Auditor General shall perform such special duties as many be specified by the Executive Council". Those du• Title: Tuesday, December 8, 1981 2:30 p.m. ties have been specified and communicated, to give a full and complete review of the matter by the Auditor Gener• al. If members of the opposition believe other matters [The House met at 2:30 p.m.] should be considered they, together with any other member of the public, may communicate directly to the Auditor General. If he wishes, he can give the communi• PRAYERS cation the weight he believes such communication deserves. [Mr. Speaker in the Chair] MR. R. SPEAKER: Mr. Speaker, a supplementary ques• tion. In light of the answer, will the Premier consider an amendment to The Auditor General Act which would head: ORAL QUESTION PERIOD give status to members of this Legislature in terms of communication with the Auditor General — formal sta• Heritage Savings Trust Fund Auditing tus, as the status of the Executive Council, as the status of this Legislative Assembly as a whole? MR. R. SPEAKER: Mr. Speaker, my question this af• ternoon is to the Premier, with regard to the letter tabled MR. LOUGHEED: Mr. Speaker, obviously the hon. in the Legislature yesterday. I wonder if the Premier has Leader of the Opposition is having some difficulty read• had an opportunity to review that letter and has made a ing these Acts. Section 17(1) reads: "The Auditor General decision to forward it to the Auditor General, giving the shall perform such special duties as may be specified by tabled letter from Mr.