In the Democratic Republic of the Congo by Adam Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I

United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual Volume I asdf DEPARTMENT OF PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS DEPARTMENT OF FIELD SUPPORT AUGUST 2012 The first UN Infantry Battalion was deployed as part of United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF-I). UN infantry soldiers march in to Port Said, Egypt, in December 1956 to assume operational responsibility. asdf ‘The United Nations Infantry Battalion is the backbone of United Nations peacekeeping, braving danger, helping suffering civilians and restoring stability across war-torn societies. We salute your powerful contribution and wish you great success in your life-saving work.’ BAN Ki-moon United Nations Secretary-General United Nations Infantry Battalion Manual ii Preface I am very pleased to introduce the United Nations Infantry Battalion Man- ual, a practical guide for commanders and their staff in peacekeeping oper- ations, as well as for the Member States, the United Nations Headquarters military and other planners. The ever-changing nature of peacekeeping operations with their diverse and complex challenges and threats demand the development of credible response mechanisms. In this context, the military components that are deployed in peacekeeping operations play a pivotal role in maintaining safety, security and stability in the mission area and contribute meaningfully to the achievement of each mission mandate. The Infantry Battalion con- stitutes the backbone of any peacekeeping -

The Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and Current Developments

The Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and Current Developments Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs February 4, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40108 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Democratic Republic of Congo: Background and Current Developments Summary In October 2008, the forces of the National Congress for the Defense of the Congolese People (CNDP), under the command of General Laurent Nkunda, launched a major offensive against the Democratic Republic of Congo Armed Forces (FARDC) in eastern Congo. Within days, the CNDP captured a number of small towns and Congolese forces retreated in large numbers. Eastern Congo has been in a state of chaos for over a decade. The first rebellion to oust the late President Mobutu Sese Seko began in the city of Goma in the mid-1990s. The second rebellion in the late 1990s began also in eastern Congo. The root causes of the current crisis are the presence of over a dozen militia and extremist groups, both foreign and Congolese, in eastern Congo, and the failure to fully implement peace agreements signed by the parties. Over the past 14 years, the former Rwandese armed forces and the Interhamwe militia have been given a safe haven in eastern Congo and have carried out many attacks inside Rwanda and against Congolese civilians. A Ugandan rebel group, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), is also in Congo, despite an agreement reached between the LRA and the Government of Uganda. In November 2008, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon appointed former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo as his envoy to help broker a peace agreement to end the crisis in eastern Congo. -

UNICEF DRC Evaluation Report 2007-2011 Programme for The

ICC-01/04-01/06-3344-Anx23-tENG 12-12-2017 1/88 EK T UNICEF DRC Evaluation Report 2007-2011 Programme for the Reintegration of Children Associated with Armed Forces and Armed Groups in the DRC Sylvie Bodineau May-June 2011 Official Court Translation ICC-01/04-01/06-3344-Anx23-tENG 12-12-2017 2/88 EK T Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 1- What has been done................................................................................................................ 10 1.1 Different types of intervention depending on the geopolitical context, the CPAs present and the availability of funding.................................................................................................................. 10 1.2 UNICEF’s role............................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 Situation in June 2011............................................................................................................. -

Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC)

Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) “ Sicherheit und Entwicklung – zwei Seiten einer Medaille ? “ Werner Rauber, Head Peacekeeping Studies Department am KAIPTC Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) Vernetzte Sicherheit und Entwicklung in Afrika Das Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) in Accra / Ghana - Zielsetzung und Erfahrungen Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) Wo liegt Ghana? Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) Großfriedrichsburg Gebäude im Fort Großfriedrichsburg nach einer Vorgabe aus dem Jahre 1708 Gebäude im Fort Großfriedrichsburg im März 2009 Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) Jan 2004 2 Sep 2002 23 Sep 2003 Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre (KAIPTC) History 1998 Direktive zur Einrichtung des KAIPTC veröffentlicht 2001 Arbeitsbeginn Kommandant und Planungsstab Jan 2002 Deutschland gewährt eine Anschubfinanzierung von €2.6M Mar 2002 Zielvorgabe und Realisierungsplan erstellt May 2002 Großbritannien steigt in die Finanzierung mit ein. Sep 2002 Baubeginn unter deutscher Bauleitung Nov 2003 Phase 1 abgeschlossen (GE funding) Nov 2003 1. Kurs ( DDR ) am KAIPTC durchgeführt Jan 2004 Offizielle Eröffnung am 24. Januar 2004 Late 2005 Abschluss Phase 2 (UK/NL/IT funding) Ab 06/2006 Weiterentwicklung Organisations-/Managmentstruktur Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping TrainingMess Centre (KAIPTC) -

Democratic Republic of the Congo INDIVIDUALS

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:18/02/2021 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: Democratic Republic of the Congo INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: BADEGE 1: ERIC 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1971. Nationality: Democratic Republic of the Congo Address: Rwanda (as of early 2016).Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DRC0028 (UN Ref): CDi.001 (Further Identifiying Information):He fled to Rwanda in March 2013 and is still living there as of early 2016. INTERPOL-UN Security Council Special Notice web link: https://www.interpol.int/en/notice/search/un/5272441 (Gender):Male Listed on: 23/01/2013 Last Updated: 20/01/2021 Group ID: 12838. 2. Name 6: BALUKU 1: SEKA 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: --/--/1977. a.k.a: (1) KAJAJU, Mzee (2) LUMONDE (3) LUMU (4) MUSA Nationality: Uganda Address: Kajuju camp of Medina II, Beni territory, North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo (last known location).Position: Overall leader of the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) (CDe.001) Other Information: (UK Sanctions List Ref):DRC0059 (UN Ref):CDi.036 (Further Identifiying Information):Longtime member of the ADF (CDe.001), Baluku used to be the second in command to ADF founder Jamil Mukulu (CDi.015) until he took over after FARDC military operation Sukola I in 2014. Listed on: 07/02/2020 Last Updated: 31/12/2020 Group ID: 13813. 3. Name 6: BOSHAB 1: EVARISTE 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. -

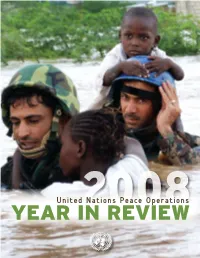

Year in Review 2008

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Policy Issues

Executive Board Second Regular Session Rome, 4–7 November 2013 POLICY ISSUES Agenda item 4 For approval WFP'S ROLE IN PEACEBUILDING IN TRANSITION SETTINGS EE Distribution: GENERAL WFP/EB.2/2013/4-A/Rev.1 25 October 2013 This document is printed in a limited number of copies. Executive Board documents are ORIGINAL: ENGLISH available on WFP’s Website (http://executiveboard.wfp.org). 2 WFP/EB.2/2013/4-A/Rev.1 NOTE TO THE EXECUTIVE BOARD This document is submitted to the Executive Board for approval. The Secretariat invites members of the Board who may have questions of a technical nature with regard to this document to contact the WFP staff focal points indicated below, preferably well in advance of the Board’s meeting. Director, OSZ*: Mr S. Samkange Email: [email protected] Chief, OSZPH**: Mr P. Howe Email: [email protected] Should you have any questions regarding availability of documentation for the Executive Board, please contact the Conference Servicing Unit (tel.: 066513-2645). * Policy, Programme, and Innovation Division ** Humanitarian Crises and Transitions Unit WFP/EB.2/2013/4-A/Rev.1 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Conflict is a leading cause of hunger. People in conflict-affected states are up to three times more likely to be undernourished than those living in countries at peace.1 To a lesser extent, hunger can contribute to violence by exacerbating tensions and grievances. WFP therefore has a strong interest and a potentially important role in supporting transitions towards peace. In recent years, the United Nations’ method for supporting countries emerging from conflict has shifted to a “whole-of-government” approach with a focus on national peacebuilding strategies and the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States. -

U.N. Peacekeeping Operations in Africa

U.N. Peacekeeping Operations in Africa September 23, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45930 SUMMARY R45930 U.N. Peacekeeping Operations in Africa September 23, 2019 Many Members of Congress have demonstrated an interest in the mandates, effectiveness, and funding status of United Nations (U.N.) peacekeeping operations in Africa as an integral Luisa Blanchfield component of U.S. policy toward Africa and a key tool for fostering greater stability and security Specialist in International on the continent. As of September 2019, there are seven U.N. peacekeeping operations in Africa: Relations the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in the Central African Alexis Arieff Republic (MINUSCA), Specialist in African Affairs the U.N. Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the U.N. Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA), Lauren Ploch Blanchard Specialist in African Affairs the U.N. Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), the U.N. Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO), the African Union-United Nations Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), and the U.N. Mission for the Organization of a Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). The United States, as a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council, plays a key role in establishing, renewing, and funding U.N. peacekeeping operations, including those in Africa. For 2019, the U.N. General Assembly assessed the U.S. share of U.N. peacekeeping operation budgets at 27.89%; since the mid-1990s Congress has capped the U.S. payment at 25% due to concerns that the current assessment is too high. During the Trump Administration, the United States generally has voted in the Security Council for the renewal and funding of existing U.N. -

Reputation As a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected]

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2019 Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations Kristina Daugirdas University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/2035 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the International Humanitarian Law Commons, Organizations Law Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Daugirdas, Kristina. "Reputation as a Disciplinarian of International Organizations." Am. J. Int'l L. 113, no. 2 (2019): 221-71. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright © 2019 by The American Society of International Law doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.122 REPUTATION AS A DISCIPLINARIAN OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS By Kristina Daugirdas* ABSTRACT As a disciplinarian of international organizations, reputation has serious shortcomings. Even though international organizations have strong incentives to maintain a good reputation, reputational concerns will sometimes fail to spur preventive or corrective action. Organizations have multiple audiences, so efforts to preserve a “good” reputation may pull organizations in many different directions, and steps taken to preserve a good reputation will not always be salutary. Recent incidents of sexual violence by UN peacekeepers in the Central African Republic illustrate these points. On April 29, 2015, The Guardian published an explosive story based on a leaked UN document.1 The document described allegations against French troops who had been deployed to the Central African Republic pursuant to a mandate established by the Security Council. -

Of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO

Assessing the of the United Nations Mission in the DRC / MONUC – MONUSCO REPORT 3/2019 Publisher: Norwegian Institute of International Affairs Copyright: © Norwegian Institute of International Affairs 2019 ISBN: 978-82-7002-346-2 Any views expressed in this publication are those of the author. Tey should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. Te text may not be re-published in part or in full without the permission of NUPI and the authors. Visiting address: C.J. Hambros plass 2d Address: P.O. Box 8159 Dep. NO-0033 Oslo, Norway Internet: effectivepeaceops.net | www.nupi.no E-mail: [email protected] Fax: [+ 47] 22 99 40 50 Tel: [+ 47] 22 99 40 00 Assessing the Efectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC (MONUC-MONUSCO) Lead Author Dr Alexandra Novosseloff, International Peace Institute (IPI), New York and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs (NUPI), Oslo Co-authors Dr Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Prof. Tomas Mandrup, Stellenbosch University, South Africa, and Royal Danish Defence College, Copenhagen Aaron Pangburn, Social Science Research Council (SSRC), New York Data Contributors Ryan Rappa and Paul von Chamier, Center on International Cooperation (CIC), New York University, New York EPON Series Editor Dr Cedric de Coning, NUPI External Reference Group Dr Tatiana Carayannis, SSRC, New York Lisa Sharland, Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra Dr Charles Hunt, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University, Australia Adam Day, Centre for Policy Research, UN University, New York Cover photo: UN Photo/Sylvain Liechti UN Photo/ Abel Kavanagh Contents Acknowledgements 5 Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 13 Te effectiveness of the UN Missions in the DRC across eight critical dimensions 14 Strategic and Operational Impact of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Constraints and Challenges of the UN Missions in the DRC 18 Current Dilemmas 19 Introduction 21 Section 1. -

Monusco and Drc Elections

MONUSCO AND DRC ELECTIONS With current volatility over elections in Democratic Republic of the Congo, this paper provides background on the challenges and forewarns of MONUSCO’s inability to quell large scale electoral violence due to financial and logistical constraints. By Chandrima Das, Director of Peacekeeping Policy, UN Foundation. OVERVIEW The UN Peacekeeping Mission in the Dem- ment is asserting their authority and are ready to ocratic Republic of the Congo, known by the demonstrate their ability to hold credible elec- acronym “MONUSCO,” is critical to supporting tions. DRC President Joseph Kabila stated during peace and stability in the Democratic Republic the UN General Assembly high-level week in of the Congo (DRC). MONUSCO battles back September 2018: “I now reaffirm the irreversible militias, holds parties accountable to the peace nature of our decision to hold the elections as agreement, and works to ensure political stabil- planned at the end of this year. Everything will ity. Presidential elections were set to take place be done in order to ensure that these elections on December 23 of this year, after two years are peaceful and credible.” of delay. While they may be delayed further, MONUSCO has worked to train security ser- due to repressive tactics by the government, vices across the country to minimize excessive the potential for electoral violence and fraud is use of force during protests and demonstrations. high. In addition, due to MONUSCO’s capacity However, MONUSCO troops are spread thin restraints, the mission will not be able to protect across the entire country, with less than 1,000 civilians if large scale electoral violence occurs. -

Democratic Republic of Congo

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO 350 Fifth Ave 34 th Floor New York, N.Y. 10118-3299 http://www.hrw.org (212) 290-4700 Vol. 14, No. 6 (G) – August 2002 I counted thirty bodies and bags between the dam and the small rapids, and twelve beyond the rapids. Most corpses were in underwear, and many were beheaded. On the bridges there were still many traces of blood despite attempts to cover them with sand, and on the small maize field to the left of the landing the odors were unbearable. Human Rights Watch interview, Kisangani, June 2002. A Congolese man from Kisangani covers his mouth as he nears the Tshopo bridge, the scene of summary executions by RCD-Goma troops following an attempted mutiny. (c) 2002 AFP WAR CRIMES IN KISANGANI: The Response of Rwandan-backed Rebels to the May 2002 Mutiny 1630 Connecticut Ave, N.W., Suite 500 2nd Floor, 2-12 Pentonville Road 15 Rue Van Campenhout Washington, DC 20009 London N1 9HF, UK 1000 Brussels, Belgium TEL (202) 612-4321 TEL: (44 20) 7713 1995 TEL (32 2) 732-2009 FAX (202) 612-4333 FAX: (44 20) 7713 1800 FAX (32 2) 732-0471 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] August 2002 Vol. 14, No 6 (A) DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO WAR CRIMES IN KISANGANI: The Response of Rwandan-backed Rebels to the May 2002 Mutiny I. SUMMARY...........................................................................................................................................................2 II. RECOMMENDATIONS......................................................................................................................................3