Exploring Hugo Chávez's Use of Mimetisation to Build a Populist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Chávez and Venezuela Rachel M

McNair Scholars Journal Volume 9 | Issue 1 Article 10 2005 Resistance to U.S. Economic Hegemony in Latin America: Hugo Chávez and Venezuela Rachel M. Jacques Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Jacques, Rachel M. (2005) "Resistance to U.S. Economic Hegemony in Latin America: Hugo Chávez and Venezuela," McNair Scholars Journal: Vol. 9: Iss. 1, Article 10. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/mcnair/vol9/iss1/10 Copyright © 2005 by the authors. McNair Scholars Journal is reproduced electronically by ScholarWorks@GVSU. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ mcnair?utm_source=scholarworks.gvsu.edu%2Fmcnair%2Fvol9%2Fiss1%2F10&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages Resistance to U.S. economic hegemony in Latin America: Hugo Chávez and Venezuela Abstract Introduction Recent years have seen increasing opposition On April 11, 2002, a group of to U.S. political and economic influence in senior military officers stormed the Latin America. Venezuela is a key player in presidential palace in Caracas, the the South American economy. This project capital of Venezuela. They ousted the researches the country’s history from the leftist president, Hugo Chávez, and 1950s to the present and the role of the replaced him with the more conservative U.S. in its formation. Through political Pedro Carmona. The coup had the economy, this study asks if recent political support of the business community, changes are due to the effects of U.S. policies the upper classes, the mass media, and in Venezuela. The research examines tacit support from the U.S.; however, the relationship between the two nations the de-facto government was short and the development models proposed lived (Cooper, 2002; Hellinger, 2003; by the Chávez government. -

Threats to Academic Freedom in Venezuela: Legislative Im- Positions and Patterns of Discrimination Towards University Teachers and Students

Interdisciplinary Political Studies http://siba-ese.unisalento.it/index.php/idps ISSN: 2039 -8573 (electronic version) IdPS, Issue 3(1) 2017: 145-169 DOI: 10.1285/ i20398573v3n1p145 Published in December 11, 2017 RESEARCH ARTICLE 145 Threats to Academic Freedom in Venezuela: Legislative Im- positions and Patterns of Discrimination Towards University Teachers and Students Mayda Hocevar Nelson Rivas University of Los Andes – Venezuela University of Los Andes – Venezuela David Gómez University of Zulia – Venezuela ABSTRACT As democracy is weakened and economic and social conditions deteriorate, there are increasing threats to academic freedom and autonomy in Venezuelan universities. Although academic freedom and university autonomy are legally and constitutionally recognized, public policies and ‘new legisla- tion’ undermine them. Military and paramilitary forces violently repress student protests. Frequent- ly, students are arbitrarily detained, physically attacked, and psychologically pressured through in- terrogations about their political views and their supposed "plans to destabilize the government". A parallel system of non-autonomous universities has been created under a pensée unique established by the Socialist Plans of the Nation. Discrimination has increased, both in autonomous and non- autonomous universities. This paper will expose the legal and political policies undermining aca- demic freedom in Venezuela under the governments of former president Hugo Chávez and current president Nicolás Maduro. Patterns of attacks against -

An Analysis of Cuban Influence in Venezuela and Its Support for the Bolívarian Revolution James A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville International Studies Capstone Research Papers Senior Capstone Papers 4-24-2015 Venecuba: An Analysis of Cuban Influence in Venezuela and its Support for the Bolívarian Revolution James A. Cohrs Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ international_studies_capstones Part of the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Cohrs, James A., "Venecuba: An Analysis of Cuban Influence in Venezuela and its Support for the Bolívarian Revolution" (2015). International Studies Capstone Research Papers. 1. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/international_studies_capstones/1 This Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Studies Capstone Research Papers by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VENECUBA AN ANALYSIS OF CUBAN INFLUENCE IN VENEZUELA AND ITS SUPPORT FOR THE BOLÍVARIAN REVOLUTION __________________ A Paper Presented to Dr. Jenista Cedarville University __________________ In Fulfillment of the Requirements for INTL 4850-01 __________________ By James Cohrs April 24th, 2015 Cohrs 1 Introduction "I swear before you, I swear by the God of my fathers; by my forefathers themselves, by my honor and my country, that I shall never allow my hands to be idle or my soul to rest until I have broken the shackles which bind us to Spain!" (Roberts, 1949, p. 5). Standing on a hill in Rome, this was the oath pledged by Simón Bolívar, “El Libertador”, as he began his quest to liberate the Spanish-American colonies from Spanish rule. -

Misión Madres Del Barrio: a Bolivarian Social Program Recognizing Housework and Creating a Caring Economy in Venezuela

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks MISIÓN MADRES DEL BARRIO: A BOLIVARIAN SOCIAL PROGRAM RECOGNIZING HOUSEWORK AND CREATING A CARING ECONOMY IN VENEZUELA BY Cory Fischer-Hoffman Submitted to the graduate degree program in Latin American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Committee members Elizabeth Anne Kuznesof, Phd. ____________________ Chairperson Tamara Falicov, Phd. ____________________ Mehrangiz Najafizadeh, Phd. ____________________ Date defended: May 8, 2008 The Thesis Committee for Cory Fischer-Hoffman certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: MISIÓN MADRES DEL BARRIO: A BOLIVARIAN SOCIAL PROGRAM RECOGNIZING HOUSEWORK AND CREATING A CARING ECONOMY IN VENEZUELA Elizabeth Anne Kuznesof, Phd. ________________________________ Chairperson Date approved:_______________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis is a product of years of activism in the welfare rights, Latin American solidarity, and global justice movements. Thank you to all of those who I have worked and struggled with. I would especially like to acknowledge Monica Peabody, community organizer with Parents Organizing for Welfare and Economic Rights (formerly WROC) and all of the welfare mamas who demand that their caring work be truly valued. Gracias to my compas, Greg, Wiley, Simón, Kaya, Tessa and Caro who keep me grounded and connected to movements for justice, and struggle along side me. Thanks to my thesis committee for helping me navigate through the bureaucracy of academia while asking thoughtful questions and providing valuable guidance. I am especially grateful to the feedback and editing support that my dear friends offered just at the moment when I needed it. -

Alba and Free Trade in the Americas

CUBA AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF ALTERNATIVE GLOBAL TRADE SYSTEMS: ALBA AND FREE TRADE IN THE AMERICAS LARRY CATÁ BACKER* & AUGUSTO MOLINA** ABSTRACT The ALBA (Alternativa Bolivariana para los Pueblos de Nuestra América) (Bolivarian Alternative for The People of Our America), the command economy alternative to the free trade model of globalization, is one of the greatest and least understood contributions of Cuba to the current conversation about globalization and economic harmonization. Originally conceived as a means for forging a unified front against the United States by Cuba and Venezuela, the organization now includes Nicaragua, Honduras, Dominica, and Bolivia. ALBA is grounded in the notion that globalization cannot be left to the private sector but must be overseen by the state in order to maximize the welfare of its citizens. The purpose of this Article is to carefully examine ALBA as both a system of free trade and as a nexus point for legal and political resistance to economic globalization and legal internationalism sponsored by developed states. The Article starts with an examination of ALBA’s ideology and institutionalization. It then examines ALBA as both a trade organization and as a political vehicle for confronting the power of developed states in the trade context within which it operates. ALBA remains * W. Richard and Mary Eshelman Faculty Scholar and Professor of Law, Dickinson Law School; Affiliate Professor, School of International Affairs, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania; and Director, Coalition for Peace & Ethics, Washington, D.C. The author may be contacted at [email protected]. An earlier version of this article was presented at the Conference, The Measure of a Revolution: Cuba 1959-2009, held May 7–9, 2009 at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. -

The Venezuelan Crisis, Regional Dynamics and the Colombian Peace Process by David Smilde and Dimitris Pantoulas Executive Summary

Report August 2016 The Venezuelan crisis, regional dynamics and the Colombian peace process By David Smilde and Dimitris Pantoulas Executive summary Venezuela has entered a crisis of governance that will last for at least another two years. An unsustainable economic model has caused triple-digit inflation, economic contraction, and widespread scarcities of food and medicines. An unpopular government is trying to keep power through increasingly authoritarian measures: restricting the powers of the opposition-controlled National Assembly, avoiding a recall referendum, and restricting civil and political rights. Venezuela’s prestige and influence in the region have clearly suffered. Nevertheless, the general contours of the region’s emphasis on regional autonomy and state sovereignty are intact and suggestions that Venezuela is isolated are premature. Venezuela’s participation in the Colombian peace process since 2012 has allowed it to project an image of a responsible member of the international community and thereby counteract perceptions of it as a “rogue state”. Its growing democratic deficits make this projected image all the more valuable and Venezuela will likely continue with a constructive role both in consolidating peace with the FARC-EP and facilitating negotiations between the Colombian government and the ELN. However, a political breakdown or humanitarian crisis could alter relations with Colombia and change Venezuela’s role in a number of ways. Introduction aimed to maximise profits from the country’s oil production. During his 14 years in office Venezuelan president Hugo Together with Iran and Russia, the Venezuelan government Chávez Frias sought to turn his country into a leading has sought to accomplish this through restricting produc- promotor of the integration of Latin American states and tion and thus maintaining prices. -

Triangulación Mediática Contra El Diputado Diosdado Cabello Presidente De La Asamblea Nacional De La República Bolivariana De Venezuela

República Bolivariana de Venezuela Asamblea Nacional Comisión Permanente del Poder Popular y Medios de Comunicación Caracas – Venezuela TRIANGULACIÓN MEDIÁTICA CONTRA EL DIPUTADO DIOSDADO CABELLO PRESIDENTE DE LA ASAMBLEA NACIONAL DE LA REPÚBLICA BOLIVARIANA DE VENEZUELA Informe presentado por la Subcomisión de Medios de la Asamblea Nacional Aprobado por la Comisión Permanente del Poder Popular y Medios de Comunicación en la Reunión Ordinaria de fecha miércoles 25 de marzo de 2015 y por la Sesión Plenaria de la Asamblea Nacional del día martes 21 de abril de 2015. 1 República Bolivariana de Venezuela Asamblea Nacional Comisión Permanente del Poder Popular y Medios de Comunicación Caracas – Venezuela PLANTEAMIENTO DEL PROBLEMA: Información y mentira Con fecha 27 de enero de 2015, el diario El Nacional de Caracas, en su versión digital, publica bajo el rótulo “Última hora”, la siguiente información: ESCOLTA DE DIOSDADO CABELLO LO ACUSA EN WASHINGTON DE NARCOTRÁFICO El rotativo venezolano cita como fuente al periódico de Miami, Diario las Américas. Este, a su vez, remite al español ABC como su fuente de información. A partir de esta triangulación mediática Madrid-Miami-Caracas, la información se extiende por el mundo hasta difuminarse el rastro de la fuente original y diluirse, aparentemente la responsabilidad informativa y editorial La versión de ABC aparece bajo el siguiente titular: EL ESCOLTA DEL NUMERO DOS CHAVISTA HUYE A EE.UU. Y LE ACUSA DE NARCO -Salazar testificará contra Cabello en Washington Enero 27, 2015. 2 República Bolivariana de Venezuela Asamblea Nacional Comisión Permanente del Poder Popular y Medios de Comunicación Caracas – Venezuela El lead o encabezamiento de la información precisa: “Leamsy Salazar, el que hasta ahora era jefe de seguridad del Presidente de la Asamblea de Venezuela, Diosdado Cabello, que a su vez es el número dos del régimen de Nicolás Maduro, ha huido y se encuentra en Estados Unidos. -

Cuba and Alba's Grannacional Projects at the Intersection of Business

GLOBALIZATION AND THE SOCIALIST MULTINATIONAL: CUBA AND ALBA’S GRANNACIONAL PROJECTS AT THE INTERSECTION OF BUSINESS AND HUMAN RIGHTS Larry Catá Backer The Cuban Embargo has had a tremendous effect on forts. Most of these have used the United States, and the way in which Cuba is understood in the global le- its socio-political, economic, cultural and ideological gal order. The understanding has vitally affected the values as the great foil against which to battle. Over way in which Cuba is situated for study both within the course of the last half century, these efforts have and outside the Island. This “Embargo mentality” had mixed results. But they have had one singular has spawned an ideology of presumptive separation success—they have propelled Cuba to a level of in- that, colored either from the political “left” or fluence on the world stage far beyond what its size, “right,” presumes isolation as the equilibrium point military and economic power might have suggested. for any sort of Cuban engagement. Indeed, this “Em- Like the United States, Cuba has managed to use in- bargo mentality” has suggested that isolation and ternationalism, and especially strategically deployed lack of sustained engagement is the starting point for engagements in inter-governmental ventures, to le- any study of Cuba. Yet it is important to remember verage its influence and the strength of its attempted that the Embargo has affected only the character of interventions in each of these fields. (e.g., Huish & Cuba’s engagement rather than the possibility of that Kirk 2007). For this reason, if for no other, any great engagement as a sustained matter of policy and ac- effort by Cuba to influence behavior is worth careful tion. -

A Decade Under Chávez Political Intolerance and Lost Opportunities for Advancing Human Rights in Venezuela

A Decade Under Chávez Political Intolerance and Lost Opportunities for Advancing Human Rights in Venezuela Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-371-4 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org September 2008 1-56432-371-4 A Decade Under Chávez Political Intolerance and Lost Opportunities for Advancing Human Rights in Venezuela I. Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 1 Political Discrimination ............................................................................................2 The Courts ...............................................................................................................3 -

Venezuela's Medical Revolution: Can the Cuban Medical

VENEZUELA’S MEDICAL REVOLUTION: CAN THE CUBAN MEDICAL MODEL BE APPLIED IN OTHER COUNTRIES? by Christopher Walker Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia December 2013 © Copyright by Christopher Walker, 2013 DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this research project to an old friend and mentor Therese Kaufmann. Though in her later years and facing many health challenges, her support as a friend, neighbour, tennis partner and caretaker has to be acknowledged as a pivotal person in my life growing up. Her generosity, friendship, compassion, patience and belief in me was truly extraordinary. I would also like to dedicate this to my dear friend and colleague Mahkia Eybagi, for showing many of us what it means to face real life challenges with strength, compassion, dignity and kindness. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ v LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................ vi ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... vii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS USED .......................................................................... viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................. ix CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. -

44. Costa Central: Antecedentes Históricos

www.fundacionempresaspolar.org UNIDAD NATURAL 1 3 – Fundación Empresas Polar Apartado postal 70934, Los Ruices Caracas 1071–A,Venezuela 0 0110 5 74 – Costa central J RIF paisaje humanizado ANTECEDENTES HISTÓRICOS DEL POBLAMIENTO Las primeras noticias acerca del poblamiento indígena de este territorio lámina 44 indican que, entre 8000 y 3000 años a.C., cazadores-recolectores ocupaban Producción general: Asesor ( lám. 44): Pedro Cunill Grau la región que va desde la cuenca del lago de Valencia hasta el macizo Ediciones Fundación Empresas Polar Autora: Maribel Espinoza Concepción de las estrategias de de Nirgua.Ya hacia el año 3500 a.C., en la costa central habitaban grupos edición gráfica y proyecto de diseño: dedicados a la recolecta de moluscos y a la caza menor. VACA Visión Alternativa «Vista de Maiquetía». Gustavo L. Winckelmann,1896. Hacia 1150 y 1500 d.C. los indígenas de filiación caribe se extendían fundación museos nacionales.gan.archivo cinap a la cuenca del lago de Valencia y al litoral y los valles de Aragua; también a los valles próximos a Caracas y a los valles costeros mirandinos. Para el siglo XIII ya existían asentamientos en el valle de Caracas. Desde una década antes de su fundación, en 1670, Maiquetía ALGUNAS FUNDACIONES. SIGLOS XVI–XVIII contaba con una iglesia erigida Nuestra Señora de la Concepción de Borburata (1548) Nuestra Señora de la Copacabana bajo la advocación de 1 9 Actualmente Borburata, estado Carabobo de los Guarenas (1621) Nuestra Señora de la Concepción Fundadores: Juan de Villegas y Pedro Álvarez Actualmente Guarenas, estado Miranda y San Sebastián. Nueva Valencia del Rey (1555) Santa Lucía de Pariaguán (1621) 2 10 Actualmente Valencia, estado Carabobo Actualmente Santa Lucía del Tuy, estado Miranda Fundador: Alonso Díaz Moreno Fundadores: Pedro José Gutiérrez de Lugo Santiago de León de Caracas (1567) y Gabriel de Mendoza 3 Actualmente Caracas, Dtto. -

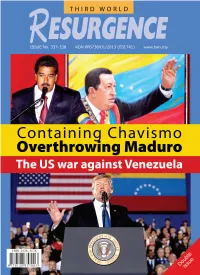

Editor's Note

Editor’s Note VENEZUELA is currently being crucified by a US- to the extent of consulting his advisers on how he could led coalition of states simply because it has chosen to trigger a war with Venezuela to seize the oilfields as embark on an alternative path of development. Such a war booty. brutal response by the US to any nation state opting Given this obsession, Trump’s first concern was for a different model of development is not in itself to ensure that the man at the helm in Venezuela was a anything new. Cuba has been the victim of US sanctions pliable person who would dutifully see to it that US since 1959 when Fidel Castro emerged victorious in interests were protected. Since Maduro did not fit the the guerilla war which toppled the corrupt US-backed bill, the only way out was regime change. In a brazen regime of Fulgencio Batista. Originally limited to the display of imperial power, Trump even effectively purchase of arms, the restrictions were subsequently nominated the candidate whom the Venezuelan people expanded to make it a more comprehensive sanctions were supposed to elect if they wanted the US to lift regime. sanctions. When Hugo Chavez became the President of The US’ man was Juan Guaido, who had been Venezuela in 1999 and proclaimed the Bolivarian groomed by an elite US-funded regime change training Revolution (a socialist political programme named after academy. Known by its acronym CANVAS, the the South American independence hero Simon Bolivar), organisation has, according to award-winning journalist the US was anything but pleased.