Copyright by Vasilina Orlova 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beneath the Surface *Animals and Their Digs Conversation Group

FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS FOR ADULTS August 2013 • Northport-East Northport Public Library • August 2013 Northport Arts Coalition Northport High School Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Courtyard Concert EMERGENCY Volunteer Fair presents Jazz for a Yearbooks Wanted GALLERY EXHIBIT 1 Registration begins for 2 3 Friday, September 27 Children’s Programs The Library has an archive of yearbooks available Northport Gallery: from August 12-24 Summer Evening 4:00-7:00 p.m. Friday Movies for Adults Hurricane Preparedness for viewing. There are a few years that are not represent- *Teen Book Swap Volunteers *Kaplan SAT/ACT Combo Test (N) Wednesday, August 14, 7:00 p.m. Northport Library “Automobiles in Water” by George Ellis Registration begins for Health ed and some books have been damaged over the years. (EN) 10:45 am (N) 9:30 am The Northport Arts Coalition, and Safety Northport artist George Ellis specializes Insurance Counseling on 8/13 Have you wanted to share your time If you have a NHS yearbook that you would like to 42 Admission in cooperation with the Library, is in watercolor paintings of classic cars with an Look for the Library table Book Swap (EN) 11 am (EN) Thursday, August 15, 7:00 p.m. and talents as a volunteer but don’t know where donate to the Library, where it will be held in posterity, (EN) Friday, August 2, 1:30 p.m. (EN) Friday, August 16, 1:30 p.m. Shake, Rattle, and Read Saturday Afternoon proud to present its 11th Annual Jazz for emphasis on sports cars of the 1950s and 1960s, In conjunction with the Suffolk County Office of to start? Visit the Library’s Volunteer Fair and speak our Reference Department would love to hear from you. -

A Film Watcher's Guide to Multicultural Films

(Year) The year stated follows the TPL catalogue, based on when the film was released in DVD format. DRAMA CONTINUED Young and Beautiful (2014) [French] La Donation (The Legacy) (2010) [French] Yureru (Sway) (2006) [Japanese] Eccentricities of a Blonde-Haired Girl (2010) FAMILY [Portuguese] Amazonia (2014) [no dialogue] Ekstra (2014) [Tagalog] Antboy (2014) [English] Everyday (2014) [English] A Film Watcher’s The Book of Life (2014) [English/Spanish/French] Force Majeure (2014) [Swedish/English/French] Jack and the Cuckoo-Clock Heart (2013) Gerontophilia (2014) [French/English] Guide To Gett: The Trial of Viviane Amsalem (2015) [English/French] Khumba (2013) [English] [French/Hebrew/Arabic] Song of the Sea (2015) [English/French] Girlhood (2015) [French] Happy-Go-Lucky (2009) [English] HORROR The hundred year-old man who climbed out of a (*includes graphic scenes/violence) window and disappeared (2015) [Swedish/English] Berberian Sound Studio (2012) [English] The Hunt (2013) [Danish] *Borgman (2013) [Dutch/English] I am Yours (2013) [Norwegian/Urdu/Swedish] *Kill List (2011) [English] Ida (2014) [Polish] The Loved Ones (2012) [English] In a Better World (2011) [Danish/French] The Wild Hunt (2010) [English/French] The Last Sentence (2012) [Swedish] Les Neiges du Kilimanjaro (The Snows of ROMANCE Kilimanjaro) (2012) [French] All about Love (2006) [Cantonese/Mandarin] Leviathan (2015) [Russian/English/French] Amour (2013) [French] Like Father, Like Son (2014) [Japanese] Cairo Time (2010) [English/French] Goodbye First Love (2011) [French] -

Gendered Mobility, Legacy and Transformative Sacrifice in the Screen Stories of Susanne Bier

Networking Knowledge Position-in-frame (Jun. 2017) Position-in-frame: gendered mobility, legacy and transformative sacrifice in the screen stories of Susanne Bier. CATH MOORE, Deakin University ABSTRACT An integral connection point between the screenplay and reader/viewer is the protagonist’s transformative journey. The construction of this narrative backbone is critical to the articulation of overarching thematic concerns and story premise but also reflects the story creator’s worldview- one often coloured by representations of gender. The Hollywood model certainly divides narrative function along gender lines but does this representation hold true within a different cultural context? This article examines the selected screen stories of Danish director Susanne Bier whose partnership with screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen is one of Denmark’s most successful film partnerships. Employing a case study methodology I examine the dramatic function of and agency afforded screen characters and the critical dynamic between cultural landscape, practitioner preference and narrative inquiry. Key to this address is an exploration of mobility, legacy and sacrifice as textual considerations of gender and its utilisation as transnational narrative strategy. KEYWORDS Transnational, mobility, transformative, collaboration, gaze Refocusing a masculinised gaze? With persistent ubiquity Hollywood continues to cast a dominant shadow over much of the global film & TV landscape. Similarly pervasive is the figurehead of such industrial influence - the male protagonist -

Estimations of Undisturbed Ground Temperatures Using Numerical and Analytical Modeling

ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING By LU XING Bachelor of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Huazhong University of Science & Technology Wuhan, China 2008 Master of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK, US 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2014 ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING Dissertation Approved: Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler Dissertation Adviser Dr. Daniel E. Fisher Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar Dr. Richard A. Beier ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler, who patiently guided me through the hard times and encouraged me to continue in every stage of this study until it was completed. I greatly appreciate all his efforts in making me a more qualified PhD, an independent researcher, a stronger and better person. Also, I would like to devote my sincere thanks to my parents, Hongda Xing and Chune Mei, who have been with me all the time. Their endless support, unconditional love and patience are the biggest reason for all the successes in my life. To all my good friends, colleagues in the US and in China, who talked to me and were with me during the difficult times. I would like to give many thanks to my committee members, Dr. Daniel E. Fisher, Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar and Dr. Richard A. Beier for their suggestions which helped me to improve my research and dissertation. -

Botanica Pacifica

Russian Academy of Sciences, Far Eastern Branch Botanical Garden-Institute botanica pacifica A journal of plant science and conservation Volume 9, No. 1 2020 VLADIVOSTOK 2020 Botanica Pacifica. A journal of plant science and conservation. 2020. 9(1): 3–52 DOI: 10.17581/bp.2020.09113 Revision of the genus Viola L. (Violaceae) in the Russian Far East with notes on adjacent territories Marc Espeut Marc Espeut ABSTRACT e-mail: [email protected] This study proposes a revision of the genus Viola L. (Violaceae) in the Russian 34, rue de l'Agriculture, 66500 Prades, Far East and adjacent regions. It is based on the taxonomic work that Becker con- France ducted on the Asian Viola (1915–1928), but also on Clausen's cytotaxonomic stud- ies (1926–1964) that laid the foundations of the genus' phylogeny. Chromosome counts, as well as phylogenetic analyses, have allowed to specify the infrageneric taxonomy and establish relationships between some taxa of American or Asian ad- Manuscript received: 09.03.2020 jacent territories. A systematic treatment based on the Biological Species Concept, Review completed: 22.04.2020 associated with genetic, cytotaxonomic, and biogeographic data, allowed many sys- Accepted for publication: 02.05.2020 tematic and nomenclatural changes, at different levels: infrageneric, specific and Published online: 07.05.2020 infraspecific. This study shows the remarkable role of the Russian Far East for the conservation and differentiation of the genus Viola species, and probably for the whole flora of the Holarctic Kingdom. Keywords: Violaceae, Viola, Russian Far East, typifications, taxonomic novelties, no- TABLE OF CONTENTS menclatural novelties Introduction .......................................................... -

A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia

Informationen der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle für jüdische Architektur in Europa bet-tfila.org/info Nr. 18 1+2/15 Fakultät 3, Technische Universität Braunschweig / Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem SPECIAL EDITION “Siberia” – SONDERAUSGABE „Sibirien“ “From Jerusalem to Birobidzhan” – A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia In August 2015, the team of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University Erstmalig erscheint aus aktuellem Anlass of Jerusalem undertook a research expedition to Siberia. Over the course of 21 eine Sonderausgabe von bet tfila.org/info: Im days, the expedition spanned 6,000 km. Overall, the CJA team visited 16 sites August 2015 konnte sich das deutsch-israe- in Siberia and the Russian Far East: Tomsk, Mariinsk, Achinsk, Krasnoyarsk, lische Team des Center for Jewish Art und Kansk, Nizhneudinsk, Irkutsk, Babushkin (former Mysovsk), Kabansk, Ulan- der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle einen lange Ude (former Verkhneudinsk), Barguzin, Petrovsk Zabaikalskii (former Petrovskii gehegten Wunsch erfüllen und das jüdische Zavod), Chita, Khabarovsk, Birobidzhan, and Vladivostok. Erbe in Sibirien und im „Fernen Osten“ Russlands dokumentieren. In drei Wochen 16 synagogues and 4 collections of ritual objects were documented alongside a legten die fünf Wissenschaftler (Prof. Aliza survey of 11 Jewish cemeteries and numerous Jewish houses. The team consisted Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. of Prof. Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. Katrin Kessler (Bet Tfila, Katrin Keßler, Dr. Anna Berezin und Archi- Braunschweig), Dr. Anna Berezin, and architect Zoya Arshavsky. The expedi- tektin Zoya Arshavsky) auf ihrer Reise von tion was made possible with the generous donations of Mrs. Josephine Urban, Tomsk nach Vladivostok über 6.000 km zu- London, and an anonymous donor. -

Load Article

Arctic and North. 2018. No. 33 55 UDC [332.1+338.1](985)(045) DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.66 The prospects of the Northern and Arctic territories and their development within the Yenisei Siberia megaproject © Nikolay G. SHISHATSKY, Cand. Sci. (Econ.) E-mail: [email protected] Institute of Economy and Industrial Engineering of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences, Kransnoyarsk, Russia Abstract. The article considers the main prerequisites and the directions of development of Northern and Arctic areas of the Krasnoyarsk Krai based on creation of reliable local transport and power infrastructure and formation of hi-tech and competitive territorial clusters. We examine both the current (new large min- ing and processing works in the Norilsk industrial region; development of Ust-Eniseysky group of oil and gas fields; gasification of the Krasnoyarsk agglomeration with the resources of bradenhead gas of Evenkia; ren- ovation of housing and public utilities of the Norilsk agglomeration; development of the Arctic and north- ern tourism and others), and earlier considered, but rejected, projects (construction of a large hydroelectric power station on the Nizhnyaya Tunguska river; development of the Porozhinsky manganese field; place- ment of the metallurgical enterprises using the Norilsk ores near Lower Angara region; construction of the meridional Yenisei railroad and others) and their impact on the development of the region. It is shown that in new conditions it is expedient to return to consideration of these projects with the use of modern tech- nologies and organizational approaches. It means, above all, formation of the local integrated regional pro- duction systems and networks providing interaction and cooperation of the fuel and raw, processing and innovative sectors. -

Stephanie Hampton Et Al. “Sixty Years of Environmental Change in the World’S Deepest Freshwater Lake—Lake Baikal, Siberia,” Global Change Biology, August 2008

LTEU 153GS —Environmental Studies in Russia: Lake Baikal Lake Baikal in Siberia, Russia is approximately 25 million years old, the deepest and oldest lake in the world, holding more than 20% of earth’s fresh water, and providing a home to 2500 animal species and 1000 plant species. It is at risk of being irreparably harmed due to increasing and varied pollution and climate change. It has a rich history and culture for Russians and the many indigenous cultures surrounding it. It is the subject of social activism and public policy debate. Our course will explore the physical and biological characteristics of Lake Baikal, the risks to its survival, and the changes already observed in the ecosystem. We will also explore its cultural significance in the arts, literature, and religion, as well as political, historical, and economic issues related to it. Class will be run largely as a seminar. Each student will be expected to contribute based on their own expertise, life experience, and active learning. As a final project, student groups will draw on their own research and personal experiences with Lake Baikal to form policy proposals and a media campaign supporting them. Week 1: Biology and Geology of Lake Baikal Moscow: Meet with Environmental Group, Visit Zaryadye Park (Urban Development) Irkutsk Local Field Trip: Baikal Limnological Museum—forms of life in and around Lake Baikal Week 2: Threats to the Baikal Environment Local Field Trip: Irkutsk Dump, Baikal Interactive Center/Service Work Traveling Field Trip: Balagansk/Angara River, Anthropogenic Effects on Environment Weeks 3/4: Economics and Politics of Lake Baikal, Lake Baikal in Literature and Culture Traveling Field Trip: Olkhon Island/Service Project, Service Work on Great Baikal Trail/Camping Week 5: Comparison of Environmental Issues and Policies in Russian Urban Centers St. -

Tea Practices in Mongolia a Field of Female Power and Gendered Meanings

Gaby Bamana University of Wales Tea Practices in Mongolia A Field of Female Power and Gendered Meanings This article provides a description and analysis of tea practices in Mongolia that disclose features of female power and gendered meanings relevant in social and cultural processes. I suggest that women’s gendered experiences generate a differentiated power that they engage in social actions. Moreover, in tea practices women invoke meanings that are also differentiated by their gendered experience and the powerful position of meaning construction. Female power, female identity, and gendered meanings are distinctive in the complex whole of cultural and social processes in Mongolia. This article con- tributes to the understudied field of tea practices in a country that does not grow tea, yet whose inhabitants have turned this commodity into an icon of social and cultural processes in everyday life. keywords: female power—gendered meanings—tea practices—Mongolia— female identity Asian Ethnology Volume 74, Number 1 • 2015, 193–214 © Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture t the time this research was conducted, salty milk tea (süütei tsai; сүүтэй A цай) consumption was part of everyday life in Mongolia.1 Tea was an ordi- nary beverage whose most popular cultural relevance appeared to be the expres- sion of hospitality to guests and visitors. In this article, I endeavor to go beyond this commonplace knowledge and offer a careful observation and analysis of social practices—that I identify as tea practices—which use tea as a dominant symbol. In tea practices, people (women in most cases) construct and/or reappropri- ate the meaning of their gendered identity in social networks of power. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

The Bratsk-Ilimsk Territorial Production Complex: a Field Study Report

THE BRATSK-ILIMSK TERRITORIAL PRODUCTION COMPLEX: A FIELD STUDY REPORT H. Knop and A. Straszak, Editore RR-78-2 May 1978 Research Reports provide the formal record of research conducted by the International lnstitute for Applied Systems Analysis. They are carefully reviewed before publication and represent, in the Institute's best judgment, competent scientific work. Views or opinions expressed therein, however, do not necessarily reflect those of the National Member Organizations supporting the lnstitute or of the lnstitute itself. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis A-236 1 Laxenburg, Austria Copyright @ 1978 IIASA AU ' hts reserved. No part of this publication may be repro7 uced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publieher. Preface The Management and Technology Area of IIASA has carried out case studies of large-scale development programs since 1975. The purpose of these studies is to examine successful programs of regional development from an international perspective, with a multidisciplinary team of scientists skilled in the use of systems analysis. The study of the Bratsk-Ilimsk Territorial Production Complex (BITPC) represents an interim effort in our research activities. The first study was of the Tennessee Valley Authority in the United States*, forthcoming is the study of the Shinkansen development program in Japan. The present Report covers six major aspects of the BITPC program: goals, variants, and strategies; planning and organization; model calculations and computer applications; integration of environmental factors; energy supply systems; and water resources. It is hoped that the experience of the Soviet scientists and practitioners and the observations and suggestions of the study team will ~rovidethe IIASA National Member Organizations" with insights into problem solving in the management, planning, and organization of large-scale development programs. -

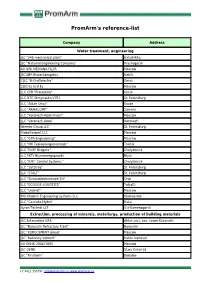

Promarm's Reference-List

PromArm's reference-list Company Address Water treatment, engineering JSC "345 mechanical plant" Balashikha JSC "National Engineering Company" Krasnogorsk AO NPK MEDIANA-FILTR Moscow JSC NPP Biotechprogress Kirishi CJSC "B-Graffelectro" Omsk CJSC Es End Ey Moscow LLC CPB "Protection" Omsk LLC NTC Stroynauka-VITU St. Petersburg LLC "Aidan Stroy" Kazan LLC "ARMACOMP" Samara LLC "Voronezh-Aqua Invest" Moscow LLC "Voronezh-Aqua" Voronezh Hermes Group LLC St. Petersburg Globaltexport LLC Moscow LLC "GPA Engineering" Moscow LLC "MK Teploenergomontazh" Troitsk LLC "NVK" Niagara " Chelyabinsk LLC PKTs Biyskenergoproekt Biysk LLC "RPK" Control Systems " Chelyabinsk LLC "SetStroy" St. Petersburg LLC "STALT" St. Petersburg LLC "Stroisantechservice-1N" Orsk LLC "ECOLINE-LOGISTICS" Tolyatti LLC "Unimet" Moscow PKK Modern Engineering Systems LLC Vladivostok LLC "Cascade-Hydro" Baku Ayron-Technik LLP Ust-Kamenogorsk Extraction, processing of minerals, metallurgy, production of building materials JSC Aldanzoloto GRK Aldan ulus, pos. Lower Kuranakh JSC "Borovichi Refractory Plant" Borovichi JSC "EUROCEMENT group" Moscow JSC "Katavsky cement" Katav-Ivanovsk AO OKHK URALCHEM Moscow JSC OEMK Stary Oskol-15 JSC "Firstborn" Bodaibo +7 8412 350797, [email protected], www.promarm.ru JSC "Aleksandrovsky Mine" Mogochinsky district of Davenda JSC RUSAL Ural Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "SUAL" Kamensk-Uralsky JSC "Khiagda" Bounty district, with. Bagdarin JSC "RUSAL Sayanogorsk" Sayanogorsk CJSC "Karabashmed" Karabash CJSC "Liskinsky gas silicate" Voronezh CJSC "Mansurovsky career management" Istra district, Alekseevka village Mineralintech CJSC Norilsk JSC "Oskolcement" Stary Oskol CJSC RCI Podolsk Refractories Shcherbinka Bonolit OJSC - Construction Solutions Old Kupavna LLC "AGMK" Amursk LLC "Borgazobeton" Boron Volga Cement LLC Nizhny Novgorod LLC "VOLMA-Absalyamovo" Yutazinsky district, with. Absalyamovo LLC "VOLMA-Orenburg" Belyaevsky district, pos.