A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches. -

A Region with Special Needs the Russian Far East in Moscow’S Policy

65 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’s pOLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer NUMBER 65 WARSAW JUNE 2017 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’S POLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak EDITOR Katarzyna Kazimierska CO-OPERATION Halina Kowalczyk, Anna Łabuszewska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH PHOTOgrAPH ON COVER Mikhail Varentsov, Shutterstock.com DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-06-7 Contents THESES /5 INTRODUctiON /7 I. THE SPEciAL CHARActERISticS OF THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST AND THE EVOLUtiON OF THE CONCEPT FOR itS DEVELOPMENT /8 1. General characteristics of the Russian Far East /8 2. The Russian Far East: foreign trade /12 3. The evolution of the Russian Far East development concept /15 3.1. The Soviet period /15 3.2. The 1990s /16 3.3. The rule of Vladimir Putin /16 3.4. The Territories of Advanced Development /20 II. ENERGY AND TRANSPORT: ‘THE FLYWHEELS’ OF THE FAR EAST’S DEVELOPMENT /26 1. The energy sector /26 1.1. The resource potential /26 1.2. The infrastructure /30 2. Transport /33 2.1. Railroad transport /33 2.2. Maritime transport /34 2.3. Road transport /35 2.4. -

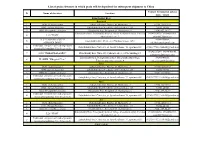

List of Grain Elevators in Which Grain Will Be Deposited for Subsequent Shipment to China

List of grain elevators in which grain will be deposited for subsequent shipment to China Contact Infromation (phone № Name of elevators Location num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky district, village Starotsuruhaytuy, Pertizan 89145160238, 89644638969, 4 LLS "PION" Shestakovich str., 3 [email protected] LLC "ZABAYKALSKYI 89144350888, 5 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 149/1 AGROHOLDING" [email protected] Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 6 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich 89242727249, 89144700140, 7 OOO "ZABAYKALAGRO" Zabaykalsky krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 147A, building 15 [email protected] Zabaykalsky krai, Priargunsky district, Staroturukhaitui village, 89245040356, 8 IP GKFH "Mungalov V.A." Tehnicheskaia street, house 4 [email protected] Corn 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 4 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich Rice 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. -

Trip Report Buryatia 2004

BURYATIA & SOUTH-WESTERN SIBERIA 10/6-20/7 2004 Petter Haldén Sanders väg 5 75263 Uppsala, Sweden [email protected] The first two weeks: 14-16/6 Istomino, Selenga delta (Wetlands), 16/6-19/6 Vydrino, SE Lake Baikal (Taiga), 19/6-22/6 Arshan (Sayan Mountains), 23/6-26/6 Borgoi Hollow (steppe). Introduction: I spent six weeks in Siberia during June and July 2004. The first two weeks were hard-core birding together with three Swedish friends, Fredrik Friberg, Mikael Malmaeus and Mats Waern. We toured Buryatia together with our friend, guide and interpreter, Sergei, from Ulan-Ude in the east to Arshan in the west and down to the Borgoi Hollow close to Mongolia. The other 4 weeks were more laid-back in terms of birding, as I spend most of the time learning Russian. The trip ended in Novosibirsk where I visited a friend together with my girlfriend. Most of the birds were hence seen during the first two weeks but some species and numbers were added during the rest of the trip. I will try to give road-descriptions to the major localities visited. At least in Sweden, good maps over Siberia are difficult to merchandise. In Ulan-Ude, well-stocked bookshops sell good maps and the descriptions given here are based on maps bought in Siberia. Some maps can also be found on the Internet. I have tried to transcript the names of the areas and villages visited from Russian to English. As I am not that skilled in Russian yet, transcript errors are probably frequent! I visited Buryatia and the Novosibirsk area in 2001 too, that trip report is also published on club300.se. -

Load Article

Arctic and North. 2018. No. 33 55 UDC [332.1+338.1](985)(045) DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.66 The prospects of the Northern and Arctic territories and their development within the Yenisei Siberia megaproject © Nikolay G. SHISHATSKY, Cand. Sci. (Econ.) E-mail: [email protected] Institute of Economy and Industrial Engineering of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences, Kransnoyarsk, Russia Abstract. The article considers the main prerequisites and the directions of development of Northern and Arctic areas of the Krasnoyarsk Krai based on creation of reliable local transport and power infrastructure and formation of hi-tech and competitive territorial clusters. We examine both the current (new large min- ing and processing works in the Norilsk industrial region; development of Ust-Eniseysky group of oil and gas fields; gasification of the Krasnoyarsk agglomeration with the resources of bradenhead gas of Evenkia; ren- ovation of housing and public utilities of the Norilsk agglomeration; development of the Arctic and north- ern tourism and others), and earlier considered, but rejected, projects (construction of a large hydroelectric power station on the Nizhnyaya Tunguska river; development of the Porozhinsky manganese field; place- ment of the metallurgical enterprises using the Norilsk ores near Lower Angara region; construction of the meridional Yenisei railroad and others) and their impact on the development of the region. It is shown that in new conditions it is expedient to return to consideration of these projects with the use of modern tech- nologies and organizational approaches. It means, above all, formation of the local integrated regional pro- duction systems and networks providing interaction and cooperation of the fuel and raw, processing and innovative sectors. -

Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities

Dr. K. Warikoo 1 © Vivekananda International Foundation 2020 Published in 2020 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org Follow us on Twitter | @vifindia Facebook | /vifindia All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher Dr. K. Warikoo is former Professor, Centre for Inner Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is currently Senior Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi. This paper is based on the author’s writings published earlier, which have been updated and consolidated at one place. All photos have been taken by the author during his field studies in the region. Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities India and Eurasia have had close social and cultural linkages, as Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia, Mongolia, Buryatia, Tuva and far wide. Buddhism provides a direct link between India and the peoples of Siberia (Buryatia, Chita, Irkutsk, Tuva, Altai, Urals etc.) who have distinctive historico-cultural affinities with the Indian Himalayas particularly due to common traditions and Buddhist culture. Revival of Buddhism in Siberia is of great importance to India in terms of restoring and reinvigorating the lost linkages. The Eurasianism of Russia, which is a Eurasian country due to its geographical situation, brings it closer to India in historical-cultural, political and economic terms. -

Newell, J. 2004. the Russian Far East

Industrial pollution in the Komsomolsky, Solnechny, and Amursky regions, and in the city of Khabarovsk and its Table 3.1 suburbs, is excessive. Atmospheric pollution has been increas- Protected areas in Khabarovsk Krai ing for decades, with large quantities of methyl mercaptan in Amursk, formaldehyde, sulfur dioxide, phenols, lead, and Type and name Size (ha) Raion Established benzopyrene in Khabarovsk and Komsomolsk-on-Amur, and Zapovedniks dust prevalent in Solnechny, Urgal, Chegdomyn, Komso- molsk-on-Amur, and Khabarovsk. Dzhugdzhursky 860,000 Ayano-Maysky 1990 Between 1990 and 1999, industries in Komsomolsky and Bureinsky 359,000 Verkhne-Bureinsky 1987 Amursky Raions were the worst polluters of the Amur River. Botchinsky 267,400 Sovetsko-Gavansky 1994 High concentrations of heavy metals, copper (38–49 mpc), Bolonsky 103,600 Amursky, Nanaisky 1997 KHABAROVSK zinc (22 mpc), and chloroprene (2 mpc) were found. Indus- trial and agricultural facilities that treat 40 percent or less of Komsomolsky 61,200 Komsomolsky 1963 their wastewater (some treat none) create a water defi cit for Bolshekhekhtsirsky 44,900 Khabarovsky 1963 people and industry, despite the seeming abundance of water. The problem is exacerbated because of: Federal Zakazniks Ⅲ Pollution and low water levels in smaller rivers, particular- Badzhalsky 275,000 Solnechny 1973 ly near industrial centers (e.g., Solnechny and the Silinka River, where heavy metal levels exceed 130 mpc). Oldzhikhansky 159,700 Poliny Osipenko 1969 Ⅲ A loss of soil fertility. Tumninsky 143,100 Vaninsky 1967 Ⅲ Fires and logging, which impair the forests. Udylsky 100,400 Ulchsky 1988 Ⅲ Intensive development and quarrying of mineral resourc- Khekhtsirsky 56,000 Khabarovsky 1959 es, primarily construction materials. -

Nation Making in Russia's Jewish Autonomous Oblast: Initial Goals

Nation Making in Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast: Initial Goals and Surprising Results WILLIAM R. SIEGEL oday in Russia’s Jewish Autonomous Oblast (Yevreiskaya Avtonomnaya TOblast, or EAO), the nontitular, predominately Russian political leadership has embraced the specifically national aspects of their oblast’s history. In fact, the EAO is undergoing a rebirth of national consciousness and culture in the name of a titular group that has mostly disappeared. According to the 1989 Soviet cen- sus, Jews compose only 4 percent (8,887/214,085) of the EAO’s population; a figure that is decreasing as emigration continues.1 In seeking to uncover the reasons for this phenomenon, I argue that the pres- ence of economic and political incentives has motivated the political leadership of the EAO to employ cultural symbols and to construct a history in its effort to legitimize and thus preserve its designation as an autonomous subject of the Rus- sian Federation. As long as the EAO maintains its status as one of eighty-nine federation subjects, the political power of the current elites will be maintained and the region will be in a more beneficial position from which to achieve eco- nomic recovery. The founding in 1928 of the Birobidzhan Jewish National Raion (as the terri- tory was called until the creation of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast in 1934) was an outgrowth of Lenin’s general policy toward the non-Russian nationalities. In the aftermath of the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks faced the difficult task of consolidating their power in the midst of civil war. In order to attract the support of non-Russians, Lenin oversaw the construction of a federal system designed to ease the fears of—and thus appease—non-Russians and to serve as an example of Soviet tolerance toward colonized peoples throughout the world. -

Stephanie Hampton Et Al. “Sixty Years of Environmental Change in the World’S Deepest Freshwater Lake—Lake Baikal, Siberia,” Global Change Biology, August 2008

LTEU 153GS —Environmental Studies in Russia: Lake Baikal Lake Baikal in Siberia, Russia is approximately 25 million years old, the deepest and oldest lake in the world, holding more than 20% of earth’s fresh water, and providing a home to 2500 animal species and 1000 plant species. It is at risk of being irreparably harmed due to increasing and varied pollution and climate change. It has a rich history and culture for Russians and the many indigenous cultures surrounding it. It is the subject of social activism and public policy debate. Our course will explore the physical and biological characteristics of Lake Baikal, the risks to its survival, and the changes already observed in the ecosystem. We will also explore its cultural significance in the arts, literature, and religion, as well as political, historical, and economic issues related to it. Class will be run largely as a seminar. Each student will be expected to contribute based on their own expertise, life experience, and active learning. As a final project, student groups will draw on their own research and personal experiences with Lake Baikal to form policy proposals and a media campaign supporting them. Week 1: Biology and Geology of Lake Baikal Moscow: Meet with Environmental Group, Visit Zaryadye Park (Urban Development) Irkutsk Local Field Trip: Baikal Limnological Museum—forms of life in and around Lake Baikal Week 2: Threats to the Baikal Environment Local Field Trip: Irkutsk Dump, Baikal Interactive Center/Service Work Traveling Field Trip: Balagansk/Angara River, Anthropogenic Effects on Environment Weeks 3/4: Economics and Politics of Lake Baikal, Lake Baikal in Literature and Culture Traveling Field Trip: Olkhon Island/Service Project, Service Work on Great Baikal Trail/Camping Week 5: Comparison of Environmental Issues and Policies in Russian Urban Centers St. -

Irkutsk's Cold Spring by Gregory Feiffer

Irkutsk's Cold Spring By Gregory Feiffer IRKUTSK, Eastern Siberia Stepping onto the airfield five time zones east of Moscow, I braced myself for the cold. Minus 12 degrees Celsius in April was a rude shock nonetheless. On top of that came snow brought by winds sweeping the vast continental steppe, altering direction to change the weather by bringing blizzards one minute and bright sun the next. "If only we didn't have to suffer through the winter each year," an Irkutsk native glumly told me later, "then we'd have far fewer problems." Of course, it would be easier to envision our solar system without the sun, so central is winter to life here. I wasn't thinking about weather patterns initially while rattling across the Irkutsk airfield at five in the morning, however. I was breathing sighs of relief that I was finally out of earshot of an angry and intricately made-up female fel- low passenger on whom I'd very recently spilled my one glass of Aeroflot water while getting up to visit the toilet. Good I hadn't opted for red wine. My sensitivity to the climate picked up again when the old ZIL truck pulling the ancient airfield shuttle stalled while shifting gears in front of the airport's three equally ancient military Tupolev cargo planes. By the time got inside the main building accessible only after leaving the airfield and finding one's way intuitively to the front entrance I was freezing. assumed that since I'd flown from Moscow, I needed the domestic-flights building. -

Cultural Landscapes and the Formation of Local

CBU INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON INNOVATION, TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER AND EDUCATION MARCH 25-27, 2015, PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC WWW.CBUNI.CZ, OJS.JOURNALS.CZ CULTURAL LANDSCAPES AND LOCAL IDENTITIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF EASTERN SIBERIAN CITIES (FROM LATE 18TH TO EARLY 19TH CENTURY) Maria Mihailovna Plotnikova1 Abstract: This article considers the interaction of geographical and cultural landscape in identity formation of the East-Siberian cities of Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Kirensk in the late 18th century and early 19th century. The comparative analysis of the European city of Valga with the East-Siberian city of Kirensk revealed that, while most of the citizens of the European city were artisans, the military personnel played a significant role in the outskirts of the Russian Empire. At the end of 18th century and during the early 19th century, the Eastern Siberian cities collected taxes as revenue for the city, using the advantage of their geographical position. The author concludes that the study into the essence of the “genius loci” of a city gives insight into the origins of the local identity formation. UDC Classification: 94(571.53), DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12955/cbup.v3.614 Keywords: cultural landscape, city identity, city incomes, East-Siberian cities, Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Kirensk, Valga, comparative analysis Introduction The study of a cultural landscape uncovers relationships between space and local identity, and space and culture, to understand the influence of landscape on the urban environment. The local identity in this case relates to the “essence of place.” This present work attempts to show the formation of this identity in the Siberian cities of Irkutsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Kirensk, in terms of the “genius loci” (the location’s prevailing character), and in developing the cultural landscape. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country.