Cultural Landscapes and the Formation of Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia

Informationen der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle für jüdische Architektur in Europa bet-tfila.org/info Nr. 18 1+2/15 Fakultät 3, Technische Universität Braunschweig / Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem SPECIAL EDITION “Siberia” – SONDERAUSGABE „Sibirien“ “From Jerusalem to Birobidzhan” – A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia In August 2015, the team of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University Erstmalig erscheint aus aktuellem Anlass of Jerusalem undertook a research expedition to Siberia. Over the course of 21 eine Sonderausgabe von bet tfila.org/info: Im days, the expedition spanned 6,000 km. Overall, the CJA team visited 16 sites August 2015 konnte sich das deutsch-israe- in Siberia and the Russian Far East: Tomsk, Mariinsk, Achinsk, Krasnoyarsk, lische Team des Center for Jewish Art und Kansk, Nizhneudinsk, Irkutsk, Babushkin (former Mysovsk), Kabansk, Ulan- der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle einen lange Ude (former Verkhneudinsk), Barguzin, Petrovsk Zabaikalskii (former Petrovskii gehegten Wunsch erfüllen und das jüdische Zavod), Chita, Khabarovsk, Birobidzhan, and Vladivostok. Erbe in Sibirien und im „Fernen Osten“ Russlands dokumentieren. In drei Wochen 16 synagogues and 4 collections of ritual objects were documented alongside a legten die fünf Wissenschaftler (Prof. Aliza survey of 11 Jewish cemeteries and numerous Jewish houses. The team consisted Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. of Prof. Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. Katrin Kessler (Bet Tfila, Katrin Keßler, Dr. Anna Berezin und Archi- Braunschweig), Dr. Anna Berezin, and architect Zoya Arshavsky. The expedi- tektin Zoya Arshavsky) auf ihrer Reise von tion was made possible with the generous donations of Mrs. Josephine Urban, Tomsk nach Vladivostok über 6.000 km zu- London, and an anonymous donor. -

Load Article

Arctic and North. 2018. No. 33 55 UDC [332.1+338.1](985)(045) DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.66 The prospects of the Northern and Arctic territories and their development within the Yenisei Siberia megaproject © Nikolay G. SHISHATSKY, Cand. Sci. (Econ.) E-mail: [email protected] Institute of Economy and Industrial Engineering of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences, Kransnoyarsk, Russia Abstract. The article considers the main prerequisites and the directions of development of Northern and Arctic areas of the Krasnoyarsk Krai based on creation of reliable local transport and power infrastructure and formation of hi-tech and competitive territorial clusters. We examine both the current (new large min- ing and processing works in the Norilsk industrial region; development of Ust-Eniseysky group of oil and gas fields; gasification of the Krasnoyarsk agglomeration with the resources of bradenhead gas of Evenkia; ren- ovation of housing and public utilities of the Norilsk agglomeration; development of the Arctic and north- ern tourism and others), and earlier considered, but rejected, projects (construction of a large hydroelectric power station on the Nizhnyaya Tunguska river; development of the Porozhinsky manganese field; place- ment of the metallurgical enterprises using the Norilsk ores near Lower Angara region; construction of the meridional Yenisei railroad and others) and their impact on the development of the region. It is shown that in new conditions it is expedient to return to consideration of these projects with the use of modern tech- nologies and organizational approaches. It means, above all, formation of the local integrated regional pro- duction systems and networks providing interaction and cooperation of the fuel and raw, processing and innovative sectors. -

Stephanie Hampton Et Al. “Sixty Years of Environmental Change in the World’S Deepest Freshwater Lake—Lake Baikal, Siberia,” Global Change Biology, August 2008

LTEU 153GS —Environmental Studies in Russia: Lake Baikal Lake Baikal in Siberia, Russia is approximately 25 million years old, the deepest and oldest lake in the world, holding more than 20% of earth’s fresh water, and providing a home to 2500 animal species and 1000 plant species. It is at risk of being irreparably harmed due to increasing and varied pollution and climate change. It has a rich history and culture for Russians and the many indigenous cultures surrounding it. It is the subject of social activism and public policy debate. Our course will explore the physical and biological characteristics of Lake Baikal, the risks to its survival, and the changes already observed in the ecosystem. We will also explore its cultural significance in the arts, literature, and religion, as well as political, historical, and economic issues related to it. Class will be run largely as a seminar. Each student will be expected to contribute based on their own expertise, life experience, and active learning. As a final project, student groups will draw on their own research and personal experiences with Lake Baikal to form policy proposals and a media campaign supporting them. Week 1: Biology and Geology of Lake Baikal Moscow: Meet with Environmental Group, Visit Zaryadye Park (Urban Development) Irkutsk Local Field Trip: Baikal Limnological Museum—forms of life in and around Lake Baikal Week 2: Threats to the Baikal Environment Local Field Trip: Irkutsk Dump, Baikal Interactive Center/Service Work Traveling Field Trip: Balagansk/Angara River, Anthropogenic Effects on Environment Weeks 3/4: Economics and Politics of Lake Baikal, Lake Baikal in Literature and Culture Traveling Field Trip: Olkhon Island/Service Project, Service Work on Great Baikal Trail/Camping Week 5: Comparison of Environmental Issues and Policies in Russian Urban Centers St. -

Irkutsk's Cold Spring by Gregory Feiffer

Irkutsk's Cold Spring By Gregory Feiffer IRKUTSK, Eastern Siberia Stepping onto the airfield five time zones east of Moscow, I braced myself for the cold. Minus 12 degrees Celsius in April was a rude shock nonetheless. On top of that came snow brought by winds sweeping the vast continental steppe, altering direction to change the weather by bringing blizzards one minute and bright sun the next. "If only we didn't have to suffer through the winter each year," an Irkutsk native glumly told me later, "then we'd have far fewer problems." Of course, it would be easier to envision our solar system without the sun, so central is winter to life here. I wasn't thinking about weather patterns initially while rattling across the Irkutsk airfield at five in the morning, however. I was breathing sighs of relief that I was finally out of earshot of an angry and intricately made-up female fel- low passenger on whom I'd very recently spilled my one glass of Aeroflot water while getting up to visit the toilet. Good I hadn't opted for red wine. My sensitivity to the climate picked up again when the old ZIL truck pulling the ancient airfield shuttle stalled while shifting gears in front of the airport's three equally ancient military Tupolev cargo planes. By the time got inside the main building accessible only after leaving the airfield and finding one's way intuitively to the front entrance I was freezing. assumed that since I'd flown from Moscow, I needed the domestic-flights building. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Aleksei P. Okladnikov: the Great Explorer of the Past

Aleksei P. Okladnikov: The Great Explorer of the Past Volume I A biography of a Soviet archaeologist (1900s - 1950s) A. K. Konopatskii Translated from the Russian by Richard L. Bland and Yaroslav V. Kuzmin Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG ISBN 978-1-78969-232-7 ISBN 978-1-78969-233-4 (e-Pdf) © A. K. Konopatski and Archaeopress 2019 Translation © Richard L. Bland and Yaroslav V. Kuzmin 2019 Cover background: Cape Shamanskii, Lake Baikal (photo by A. V. Tetenkin); cover photo: A. P. Okladnikov near the campfire. Back cover background: View near the Teshik Tash Grotto (photo by A. I. Krivoshapkin) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by Severn, Gloucester This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of figures ..............................................................................................................................v Translators’ introduction ..................................................................................................... vii Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������x Aleksei P. Okladnikov and archaeology of Asia: a brief overview ........................... xiii References ......................................................................................................................... -

A Case Study on the Angara/Yenisey River System in the Siberian Region

land Article Optical Spectral Tools for Diagnosing Water Media Quality: A Case Study on the Angara/Yenisey River System in the Siberian Region Costas A. Varotsos 1,2 , Vladimir F. Krapivin 3, Ferdenant A. Mkrtchyan 3 and Yong Xue 2,4,* 1 Department of Environmental Physics and Meteorology, University of Athens, 15784 Athens, Greece; [email protected] 2 School of Environment Science and Geoinformatics, China University of Mining and Technology, Xuzhou 221116, China 3 Kotelnikov Institute of Radioengineering and Electronics, Fryazino Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, Fryazino, 141190 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (V.F.K.); [email protected] (F.A.M.) 4 College of Science and Engineering, University of Derby, Derby DD22 3AW, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: This paper presents the results of spectral optical measurements of hydrochemical char- acteristics in the Angara/Yenisei river system (AYRS) extending from Lake Baikal to the estuary of the Yenisei River. For the first time, such large-scale observations were made as part of a joint American-Russian expedition in July and August of 1995, when concentrations of radionuclides, heavy metals, and oil hydrocarbons were assessed. The results of this study were obtained as part of the Russian hydrochemical expedition in July and August, 2019. For in situ measurements and sampling at 14 sampling sites, three optical spectral instruments and appropriate software were used, including big data processing algorithms and an AYRS simulation model. The results show Citation: Varotsos, C.A.; Krapivin, V.F.; Mkrtchyan, F.A.; Xue, Y. Optical that the water quality in AYRS has improved slightly due to the reasonably reduced anthropogenic Spectral Tools for Diagnosing Water industrial impact. -

On the State of Conservation of the UNESCO World Heritage Property Lake Baikal (Russian Federation, No. 754) in 2014 1. Response

On the State of Conservation of the UNESCO World Heritage Property Lake Baikal (Russian Federation, No. 754) in 2014 1. Response of the Russian Federation with regard to Resolution No. 37 СОМ 7В.22 adopted by the World Heritage Committee. Concerning the activities of Baikalsk Paper and Pulp Mill Resolution of the RF Government related to the termination of recurring operations at Baikalsk Paper and Pulp Mill (hereinafter referred to as “BPPM”) is mainly caused by the intention to eliminate the negative impact of environmentally unsound production to a unique ecosystem of Lake Baikal and necessity of the Russian Federation to perform its obligations related to Lake Baikal conservation as UNESCO World Heritage property. Issues related to legislative and regulatory support are reflected in the Federal Law “On the Protection of Lake Baikal” and Resolution of the RF Government No. 643 “On Approval of the List of Activities Prohibited in the Central Ecological Zone of Lake Baikal Natural Area” (hereinafter referred to as “Resolution No. 643”, “List”) as of August 30, 2001 adopted according to the law specified prohibitions and restrictions of business activities to be taken into account when developing the plan for economy modernization of Baikalsk one-factory town. The RF Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment has made arrangements to evaluate the possibility to exclude separate business activities from the List and subsequent to the results of this work the Government of the Russian Federation adopted its Resolution No. 159 as of February 28, 2014 “On Introducing Changes in the List of Activities Prohibited in the Central Ecological Zone of Lake Baikal Natural Area”. -

Spatial Approach to the Analysis of the Employment Data in Siberia Based

Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences 7 (2016 9) 1651-1660 ~ ~ ~ УДК 519.25: 930 Spatial Approach to the Analysis of the Employment Data in Siberia Based on the 1897 Census (the Experience of Multivariate Statistical Analysis of the District’s Data) Elena A. Bryukhanova, Sergey V. Dronov and Oksana I. Chekryzhova* Altai State University 61a Lenina pr., Barnaul, 656049, Russia Received 12.03.2016, received in revised form 24.05.2016, accepted 18.06.2016 The article presents an original approach to regionalization of Siberia at the turn of 19th -20th centuries. The subdivision into districts is based on the typology of districts (uezds) in Siberia, which allows to make a more detailed spatial analysis of the data on employment of the 1897 census. The key source of the research has become an open information resource developed on the basis of the published materials of the 1897 census by the number of occupational groups, their gender, age and ethnic composition. Application of mathematical methods such as cluster analysis, post-hoc method and coefficient of cluster differences, allowed not only to identify the socio-demographic and economic types of Siberian districts, but also to rank the importance of the factors for determining the “appearance” of the districts. Further implementation of the cartographic method to analyze the sets of clusters defined spatial boundaries of socio-economic districts in Siberia. This study contributes to comprehensive understanding of the peculiarities of development of Siberian territories and enhancement of modernization processes at the turn of the 19th – 20th centuries. Keywords: Siberia, employment, database, the 1897 census, cluster analysis, cartographic analysis, regionalization. -

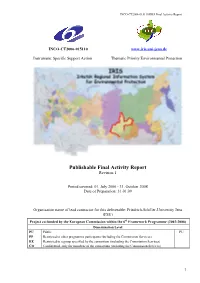

Publishable Final Activity Report Revision 1

INCO-CT2006-015110 IRIS Final Activity Report INCO-CT2006-015110 www.iris.uni-jena.de Instrument: Specific Support Action Thematic Priority:Environmental Protection Publishable Final Activity Report Revision 1 Period covered: 01. July 2006 - 31. October 2008 Date of Preparation: 31.01.09 Organisation name of lead contractor for this deliverable: Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena (FSU) Project co-funded by the European Commission within the 6th Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public PU PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) CO Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) 1 INCO-CT2006-015110 IRIS Final Activity Report Table of Contents Project Execution.............................................................................................................................. 7 1. Project Objectives..................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. The Irkutsk Region ..........................................................................................................7 2. The Consortium........................................................................................................................ 9 3. Work Performance................................................................................................................. 11 3.1. State-of-the-Art..............................................................................................................11 -

Russian Forests and Climate Change

Russian forests and What Science Can Tell Us climate change Pekka Leskinen, Marcus Lindner, Pieter Johannes Verkerk, Gert-Jan Nabuurs, Jo Van Brusselen, Elena Kulikova, Mariana Hassegawa and Bas Lerink (editors) What Science Can Tell Us 11 2020 What Science Can Tell Us Sven Wunder, Editor-In-Chief Georg Winkel, Associate Editor Pekka Leskinen, Associate Editor Minna Korhonen, Managing Editor The editorial office can be contacted at [email protected] Layout: Grano Oy Recommended citation: Leskinen, P., Lindner, M., Verkerk, P.J., Nabuurs, G.J., Van Brusselen, J., Kulikova, E., Hassegawa, M. and Lerink, B. (eds.). 2020. Russian forests and climate change. What Science Can Tell Us 11. European Forest Institute. ISBN 978-952-5980-99-8 (printed) ISBN 978-952-7426-00-5 (pdf) ISSN 2342-9518 (printed) ISSN 2342-9526 (pdf) https://doi.org/10.36333/wsctu11 Supported by: This publication was produced with the financial support of the European Union’s Partnership Instrument and the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Na- ture Conservation, and Nuclear Safety (BMU) in the context of the International Cli- mate Initiative (IKI). The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the European Forest Institute and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders. Russian forests and What Science Can Tell Us climate change Pekka Leskinen, Marcus Lindner, Pieter Johannes Verkerk, Gert-Jan Nabuurs, Jo Van Brusselen, Elena Kulikova, Mariana Hassegawa and Bas Lerink (editors) Contents Authors .............................................................................................................................. -

Land-Use/Cover Change and Driving Mechanism on the West Bank of Lake Baikal from 2005 to 2015—A Case Study of Irkutsk City

sustainability Article Land-Use/Cover Change and Driving Mechanism on the West Bank of Lake Baikal from 2005 to 2015—A Case Study of Irkutsk City Zehong Li 1,2, Yang Ren 1,2, Jingnan Li 1,2, Yu Li 1,2,*, Pavel Rykov 3, Feng Chen 1,2 and Wenbiao Zhang 1 1 Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (Y.R.); [email protected] (J.L.); [email protected] (F.C.); [email protected] (W.Z.) 2 College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 V.B. Sochava Institute of Geography Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Irkutsk 664033, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 13 July 2018; Accepted: 13 August 2018; Published: 16 August 2018 Abstract: Lake Baikal is located on the southern tableland of East Siberian Russia. The west coast of the lake has vast forest resources and excellent ecological conditions, and this area and the Mongolian Plateau constitute an important ecological security barrier in northern China. Land-use/cover change is an important manifestation of regional human activities and ecosystem evolution. This paper uses Irkutsk city, a typical city on the West Bank of Lake Baikal, as a case study area. Based on three phases of Landsat remote-sensing image data, the land-use/cover change pattern and change process are analyzed and the natural factors and socioeconomic factors are combined to reveal driving forces through the partial least squares regression (PLSR) model.