Technologies of Illusion: Enchanting Modernity's Machines by Cheryl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Version for Printing

Fermilab Today Thursday, March 27, 2008 Subscribe | Contact Fermilab Today | Archive | Classifieds Search Furlough Information Feature Fermilab Result of the Week Reminder: symmetry expands online Shedding new light An IDES representative will presence, features new blog on an old problem conduct the final on-site group meetings at 11 a.m. and noon in the Wilson Hall One West conference room on Friday, March 28. New furlough information, including an up-to-date Q&A section, appears on the furlough Web pages daily. symmetry magazine now provides more online content while it saves money by publishing fewer Layoff Information print issues. This figure shows the transverse photon New information on Fermilab From the symmetry editor: momentum in large extra dimension candidate layoffs, including an up-to-date events. The additional rate of signal events is This week's distribution of the new issue of Q&A section, appears on the shown in the open histogram along with the layoff Web pages daily. symmetry launches the next phase of the expected backgrounds. magazine's development. Our readers now Calendar use the magazine in different ways, and we When it comes to particle interactions, the are reaching a much larger audience. While force of gravity is an oddity. It is also entirely Thursday, March 27 readers are outspoken in wanting to keep the absent from the Standard Model theory. 10 a.m. print magazine, many of them are now more Although gravity is an undeniable force in our Presentations to the Physics comfortable reading online. everyday life and dominates interactions on the cosmological scale, it is by far the weakest Advisory Committee - Curia II Starting from this issue, we will publish six force at the particle level and has never been 1 p.m. -

Downloadable and Ready Crucial to Our Understanding of What It Is to Be Physiology and Biophysics, and Director of the for Re-Use in Ways the Original Human

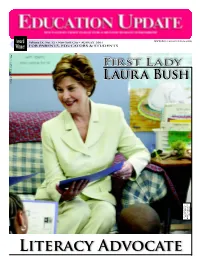

www.EDUCATIONUPDATE.com AwardAward Volume IX, No. 12 • New York City • AUGUST 2004 Winner FOR PARENTS, EDUCATORS & STUDENTS White House photo by Joyce Naltchayan First Lady Laura Bush U.S. POSTAGE PAID U.S. POSTAGE VOORHEES, NJ Permit No.500 PRSRT STD. PRSRT LITERACY ADVOCATE 2 SPOTLIGHT ON SCHOOLS ■ EDUCATION UPDATE ■ AUGUST 2004 Corporate Contributions to Education - Part I This Is The First In A Series On Corporate Contributions To Education, Interviewing Leaders Who Have Changed The Face Of Education In Our Nation DANIEL ROSE, CEO, ROSE ASSOCIATES FOCUSES ON HARLEM EDUCATIONAL ACTIVITIES FUND By JOAN BAUM, Ph.D. living in tough neighborhoods and wound up concentrating on “being effective at So what does a super-dynamic, impassioned, finding themselves in overcrowded the margin.” First HEAF took under its wing articulate humanitarian from a well known phil- classrooms. Of course, Rose is a real- the lowest-ranking public school in the city and anthropic family do when he becomes Chairman ist: He knows that the areas HEAF five years later moved it from having only 9 Emeritus, after having founded and funded a serves—Central Harlem, Washington percent of its students at grade level to 2/3rds. significant venture for educational reform? If Heights, the South Bronx—are rife Then HEAF turned its attention to a minority he’s Daniel Rose, of Rose Associates, Inc., he’s with conditions that all too easily school with 100 percent at or above grade level “bursting with pride” at having a distinguished breed negative peer pressure, poor but whose students were not successful in getting new team to whom he has passed the torch— self-esteem, and low aspirations and into the city’s premier public high schools. -

On Spiritualism

‘Light,” Jm is, 1927. A Journal of Psychical, Occult, and Mystical Research Light! More Light!”—Goethe* Whatsoever doth make Manifest is Light! ”—Paul* “>rootns c No. 2423. Vol. XLVII. (Registered as SATURDAY, JUNE 18, 1927. a Newspaper.] Price Fourpence. ?f «qs ‘ascription Obsessing Spirits. me for th* CONTENTS. months, Dr. Carl Wickland’s experiments, as set forth in yment. ft his “ Thirty Years Among the Dead,” and in his 1. rIt shoj^ Notes by the Way ............. 289 I The Passing of Francis Grierson 294 ssarily imph Captain Seton-Karr on Psychic From the Lighthouse Window 295 recent address to the London Spiritualist Alliance, Investigation.......................• 290 Informal Visit ... • • • • • • 296 offer yet another and a scientific confirmation of the Authors as Sub-Creators ... 291 Psychic Perfumes • • • • • • 297 truth of the New Testament narratives dealing with The Conduct of Circles .................292 Rays and Reflections • • • • •• 297 Spiritualism and Prohibition ... 292 A Prominent Scientist on possessing spirits which were cast out of afflicted .lore, attends Letters to the Editor ...... 293 Spiritualism • • • • • • 298 persons by Jesus and His Apostles. The “ higher ” 6 p.m., and critics and the rationalistic theologians of modern days tes willing to have long tried to get over this difficulty, one method >sible. It is, I being to suggest that Jesus and His Apostles were nade, when! NOTES BY THE WAY. naturally influenced by the superstitions of their time. Intelligent Spiritualists have long known better. They know that there are obsessing spirits, and they know The Marvel of Matter. also that these spirits are not “ devils ” in the ordinary PUBL/C I Those who find the marvels of Spiritualism a little sense of the term, but simply ignorant or darkened | too much to swallow might study with advantage some human beings who have passed into the next world, of the miracles Of the material universe. -

Continuous Project #8 Table of Contents

Continuous Project #8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Continuous Project, Introduction 7 Continuous Project, CNEAI Exhibition, May 2006 8 Allen Ruppersberg, Metamorphosis: Patriote Palloy and Harry Houdini 11 Jacques Rancière, The Emancipated Spectator 19 Seth Price, Law Poem 31 Claire Fontaine, The Ready-Made Artist and Human Strike: A Few Clarifications 33 Dan Graham, Two-Way Mirror Cylinder inside Two-Way Mirror Cube; manuscript, contributed by Karen Kelly 45 Bettina Funcke, Urgency 53 Matthew Brannon, The last thing you remember was staring at the little white tile (Hers) and The last thing you remember was staring at the little white tile (His) 59 Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt, The Public Sphere of Children 61 Mai-Thu Perret, Letter Home 67 Left Behind. A Continuous Project Symposium with Joshua Dubler 71 Tim Griffin, Rosters 79 August Bebel, Charles Fourier: His Life and His Theories 81 Maria Muhle, Equality and Public Realm according to Hannah Arendt 83 Pablo Lafuente, Image of the People, Voices of the People 91 Melanie Gilligan, The Emancipated – or Letters Not about Art 99 Simon Baier, Remarks on Installation 109 Donald Judd, ART AND INTERNATIONALISM. Prolegomena, contributed by Ei Arakawa 117 Mai-Thu Perret, Bake Sale 127 Nico Baumbach, Impure Ideas: On the Use of Badiou and Deleuze for Contemporary Film Theory 129 Serge Daney, In Stubborn Praise of Information 135 Johanna Burton, ‘Of Things Near at Hand,’ or Plumbing Cezanne’s Navel 139 Warren Niesluchowski, The Ars of Imperium 147 Summaries 158 6 CONTINOUS PROJEct #8 INTRODUctION 7 INTRODUCTION The Centre national de l’estampe et de l’art imprimé (CNEAI) invited us, as Continuous Project, to spend a month in Paris in the Spring of 2006 in order to realize a publication and an exhibition. -

It Reveals Who I Really Am”: New Metaphors, Symbols, and Motifs in Representations of Autism Spectrum Disorders in Popular Culture

“IT REVEALS WHO I REALLY AM”: NEW METAPHORS, SYMBOLS, AND MOTIFS IN REPRESENTATIONS OF AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS IN POPULAR CULTURE By Summer Joy O’Neal A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Angela Hague, Chair Dr. David Lavery Dr. Robert Petersen Copyright © 2013 Summer Joy O’Neal ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There simply is not enough thanks to thank my family, my faithful parents, T. Brian and Pamela O’Neal, and my understanding sisters, Auburn and Taffeta, for their lifelong support; without their love, belief in my strengths, patience with my struggles, and encouragement, I would not be in this position today. I am forever grateful to my wonderful director, Dr. Angela Hague, whose commitment to this project went above and beyond what I deserved to expect. To the rest of my committee, Dr. David Lavery and Dr. Robert Petersen, for their seasoned advice and willingness to participate, I am also indebted. Beyond these, I would like to recognize some “unofficial” members of my committee, including Dr. Elyce Helford, Dr. Alicia Broderick, Ari Ne’eman, Chris Foss, and Melanie Yergau, who graciously offered me necessary guidance and insightful advice for this project, particularly in the field of Disability Studies. Yet most of all, Ephesians 3.20-21. iii ABSTRACT Autism has been sensationalized by the media because of the disorder’s purported prevalence: Diagnoses of this condition that was traditionally considered to be quite rare have radically increased in recent years, and an analogous fascination with autism has emerged in the field of popular culture. -

This Is the File GUTINDEX.ALL Updated to July 5, 2013

This is the file GUTINDEX.ALL Updated to July 5, 2013 -=] INTRODUCTION [=- This catalog is a plain text compilation of our eBook files, as follows: GUTINDEX.2013 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013 with eBook numbers starting at 41750. GUTINDEX.2012 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2012 with eBook numbers starting at 38460 and ending with 41749. GUTINDEX.2011 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2011 with eBook numbers starting at 34807 and ending with 38459. GUTINDEX.2010 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2010 with eBook numbers starting at 30822 and ending with 34806. GUTINDEX.2009 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2009 with eBook numbers starting at 27681 and ending with 30821. GUTINDEX.2008 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2008 with eBook numbers starting at 24098 and ending with 27680. GUTINDEX.2007 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2007 with eBook numbers starting at 20240 and ending with 24097. GUTINDEX.2006 is a plain text listing of eBooks posted to the Project Gutenberg collection between January 1, 2006 and December 31, 2006 with eBook numbers starting at 17438 and ending with 20239. -

Jesse Shepard Papers MS 55

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c837773r No online items Guide to the Jesse Shepard Papers MS 55 Finding aid prepared by Alison Hennessey Collection processed as part of grant project supported by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) with generous funding from The Andrew Mellon Foundation. San Diego History Center Document Collection 1649 El Prado, Suite 3 San Diego, CA, 92101 619-232-6203 January 23, 2012 Guide to the Jesse Shepard MS 55 1 Papers MS 55 Title: Jesse Shepard Papers Identifier/Call Number: MS 55 Contributing Institution: San Diego History Center Document Collection Language of Material: English Physical Description: 1.5 Linear feet(3 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1868-1959 Language of Materials: Collection materials are in English, French, and Spanish. Abstract: The collection contains materials related to the musical and literary activities of Jesse Shepard, who wrote under the pen name Francis Grierson, and his long-time friend and assistant Waldemar Tonner. creator: Grierson, Francis, 1848-1927 Processing Information Collection processed by Alison Hennessey on January 23, 2012. Collection processed as part of grant project supported by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) with generous funding from The Andrew Mellon Foundation. Preferred Citation Jesse Shepard Papers, MS 55, San Diego History Center Document Collection, San Diego, CA. Separated Materials Original photographs separated to the SDHC Photograph Collection, OP14160/0-14160/35. Photographs accessible by copy negatives. Conditions Governing Access This collection is open for research. Access to “Anecdotes and Episodes: An Autobiography” is restricted to copy of original. Original photographs separated to the SDHC Photograph Collection are accessible by copy negatives. -

Ritsumeikan University

RITSUMEIKAN UNIVERSITY REPORT KYOTO innaji, located an approximate 20- In 1340, poet and Zen monk Yoshida Kenko Nminute walk from Ritsumeikan Uni- (1283-1350) wrote Essays in Idleness, a col- RITSUMEIKAN versity’s Kinugasa Campus, is one of the old- lection of 243 essays that advocate the UNIVERSITY est temples in Kyoto. The temple was foun- ideals of humility and simplicity within daily ded in 888 and was designated as a World life. One of his more famous essays is a story NEWSLETTER Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1994. The old- called “Drunkenness,“ set in Ninnaji. In the est surviving buildings date back to the 17th story, Ninnaji priests are celebrating a young century and are found in the northern half of the temple grounds, which is comprised of a large courtyard with buildings that include 4 the main hall, five-story pagoda, and a scrip- Vol.1 Issue 4 ture house. The Edo period garden and the FALL Ninnaji Historical Highlights a cultural treasure of Kyoto gates that rise above the acolyte who is about to rest of the temple are also enter the priesthood. The popular attractions. acolyte becomes drunk and puts an iron pot over Ninnaji is an important pil- his head, tightly covering grimage site for followers of his ears and nose. At the Shingon sect of Buddrism. first, the priests enjoy this In mountains north of the amusement and dance temple, pilgrims follow a happily, but when the acolyte tries to re- scaled-down version of the move the pot they find out it is stuck. -

HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY: VOLUME 1, HISTORY of PSYCHOLOGY

HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY: VOLUME 1, HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY Donald K. Freedheim Irving B. Weiner John Wiley & Sons, Inc. HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY HANDBOOK of PSYCHOLOGY VOLUME 1 HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY Donald K. Freedheim Volume Editor Irving B. Weiner Editor-in-Chief John Wiley & Sons, Inc. This book is printed on acid-free paper. ➇ Copyright © 2003 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. -

On the Cognitive Bases of Illusionism: an Untapped Tool for Brain and Behavioral Research

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 2 January 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202001.0011.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at PeerJ 2020, 8, e9712; doi:10.7717/peerj.9712 On the Cognitive Bases of Illusionism: An Untapped Tool for Brain and Behavioral Research Jordi Camí1*, Alex Gomez-Marin2 and Luis M. Martínez3 1 Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona 2 Behavior of Organisms Laboratory, Instituto de Neurociencias CSIC-UMH, Alicante 3 Visual Analogy Laboratory, Instituto de Neurociencias CSIC-UMH, Alicante * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract Cognitive scientists have paid very little attention to magic as a distinctly human activity capable of creating situations or events that are considered impossible because they violate expectations and conclude with the apparent transgression of well-established cognitive and natural laws. And even though magic techniques appeal to all known cognitive processes from sensing, attention and perception to memory and decision making, the relation between science and magic has so far been mostly unidirectional, with the primary goal of unraveling how magic works. Building up from the deconstruction of a classic magic trick, we provide here a cognitive foundation for the use of magic as a unique and largely untapped research tool to dissect cognitive processes in tasks arguably more natural than those usually exploited in artificial laboratory settings. Magicians can submerge every spectator into the precise experimental protocol they have previously designed, accounting with ease for both circumstantial and social contexts. Magicians do not base the success of their experiments in statistical measures that smear out the individual in favor of an average spectator that we know never exists in the real world. -

Modern Mysticism : and Other Essays

BOOK 104.G872 c. 1 GRIERSON # MODERN MYSTICISM 3 T1S3 OODSTSTM M T>^f^ Modern Mysticism Modern Mysticism \( And Other Essays By Francis Grierson London Constable & Company Ltd. 1910 \_All rights reserved] First Edition . 1899 Second Edition . 19 10 CHISWICK PRESS : CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON Preface SOME years ago, while living in Paris, I persuaded the author of this volume to publish an opuscule of aphorisms and short essays in French. That little book, not being intended for the general public, was neither advertised nor put on sale. It was without introduction of any kind, and was printed by an obscure publisher. Worse still, it was printed in such haste as to be full of typo- graphical errors. Notwithstanding all this, a few weeks after its appearance the author re- ceived some scores of letters from leading French writers and poets, among whom were many Academicians. But perhaps more re- markable still was the appreciation with which it was received by writers so opposed as M. Sully Prudhomme, of the French 5 6 PREFACE Academy, and M. Stephane Mallarme, the leader of les Jeunes. The former wrote of "roriginaUte puissante de la pensee de Tauteur," and the latter of the "rare emo- tion " inspired by these pages. A distinguished Italian critic, Signor En- rico Cardona, published a brochure on the little work, in the opening lines of which he defines Mr. Grierson as "un filosofo dal cuore di artista," thus making the author's name known in Italy. Dona Patrocinio de Biedma, the well-known Spanish poet and writer, translated the aphorisms and most of the short essays, and published them in several of the leading journals of Spain. -

Vol. 4 No. 16, February 11, 1909

A WEEKLY REVIEW OF POLITICS, LITERATURE, and ART No. 753 new series.Vol. IV, No. 16] THURSDAY, FEB. 11, 1909, [registered at G.P.O.]ONE PENNY CONTENTS PAGE page NOTES OF THE WEEK .,. 313 UNEDITED OPINIONS VI.-INDIAN NATIONALISM. By A. R. Orage . 320 THE POLICY OF FABIUS AGAIN. 316 MATERNITIS. By Helen George. 322 THE GREAT BYE-ELECTION JOKE. By S. D. Shallard. 316 THE SHEPHERD’S TOWER. By Eden Phillpotts. *.. 322 AN OPEN LETTER TO THE KING. By Cecil Chesterton. 317 ABRAHAM LINCOLN. By Francis Grierson. *** 323 THE DIRECTIVE ABILITY FETISH. By Edwin Pugh. 318 BOOKS AND PERSONS. By Jacob Tonson. 325 DR. RUSSEL WALLACE ON UNEMPLOYMENT. By C. D. BOOK Of THE WEEK: Recent Verse. By F. S. Flint. *a* 327 Sharp. ‘... 319 CORRESPONDENCE. 328 ALL BUSINESS COMMUNICATIONS should be ad- sturdy independence. If ten persons agree as friends dressed to the Manager, 12-14 Red Lion Court, Fleet St., London to walk from London to Oxford there is no tyranny ADVERTISEMENTS: The latest time for receiving Ad- imposed if they decline the companionship of those vertisements is first post Monday for the same week's issue. who insist on confining the excursion to the Embank- SUBSCRIPTION RATES for England and Abroad : ment. The Labour Party has, of course, had precisely Three months . 1S. 9d. the same experience with the Liberal-Labours, and the Six months . , 3s. 3d. Socialist Party, when it arises, will have the same Twelve months’ 6s. 6d. difficulty with some Socialist members of the Labour ALE remittances should be made’ payable to THE NEW AGE PRESS, Party.